805

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

The present article discusses the creation of an

elderly care model. Population aging caused by demographic and epidemiological

changes in Brazil, a relatively recent phenomenon, requires an efficient

response. Based on a critical analysis of healthcare models for the elderly,

the text presents a proposal for the healthcare of this age group, with

emphasis on low intensity levels of care, focusing on health promotion and

prevention, in order to avoid overload in the system. Integrated care models

aim to solve the problem of fragmented and poorly coordinated care in current

health systems. The more health professionals know about the history of their

patients, the better the results. This is how the contemporary and resolutive

models of care recommended by most major national and international health

agencies should function. A higher quality, more resolutive and cost-effective

care model is the focus of the present study.

INTRODUCTION

The recent phenomenon of population aging in

Brazil, caused by demographic and epidemiological changes, requires an

effective response. Based on a critical analysis of healthcare models for the

elderly, we propose the creation of a model entitled Caring Senior, emphasizing

low-intensity levels of care, focusing on health promotion and prevention, in

order to avoid burdening the system. Integrated care models aim to solve the

problem of the fragmented and poorly coordinated care that currently prevails

in health systems. We advocate an approach that prioritizes low-intensity

interventions and constant monitoring, through different care settings, as

recommended by most major national and international health agencies, which

include: integrated medical treatment, with a flowing process of educational

actions, health promotion, prevention of preventable diseases, delayed onset of

illness, early care intervention and rehabilitation from sickness.

POPULATION AGING IN

BRAZIL AND IN THE WORLD

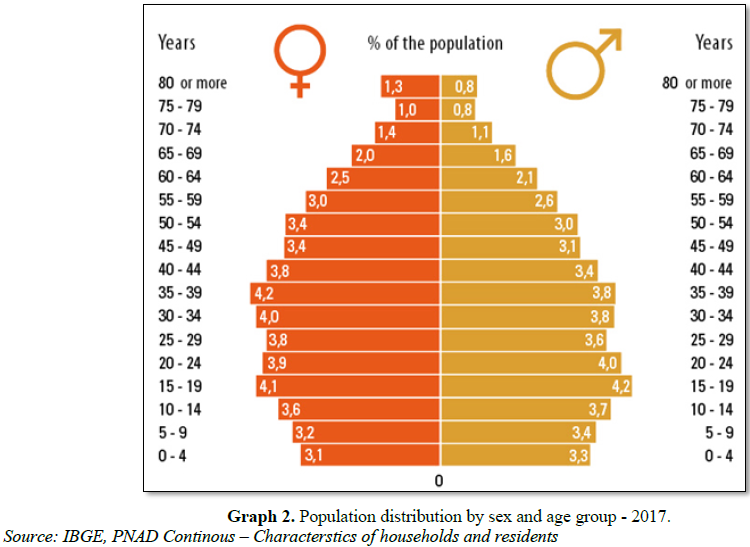

One of humankind’s greatest achievements has

been the increase in life expectancy, accompanied by a substantial improvement

in the health parameters of populations, although these achievements are

unequally distributed across countries and socioeconomic contexts. Reaching old

age, which was once the privilege of the few, has today become the norm, even

in the poorest countries. The accomplishment, however, has resulted in a major

challenge: how to add quality to the additional years of life.

The elderly have a

number of well-established health characteristics – more chronic diseases and

frailties, greater health costs and lower social and financial resources. Even

without chronic diseases, aging involves functional loss. Due to the many adverse

situations they face, care for the elderly must be structured differently from

that of adults, in order to provide special assistance. Current health services

are based around fragmentary care, with multiple specialist consultations,

little sharing of information, and numerous drugs, tests and other procedures.

This burdens the system, with a major financial impact at all levels, and does

not generate significant benefits in quality of life [3,4].

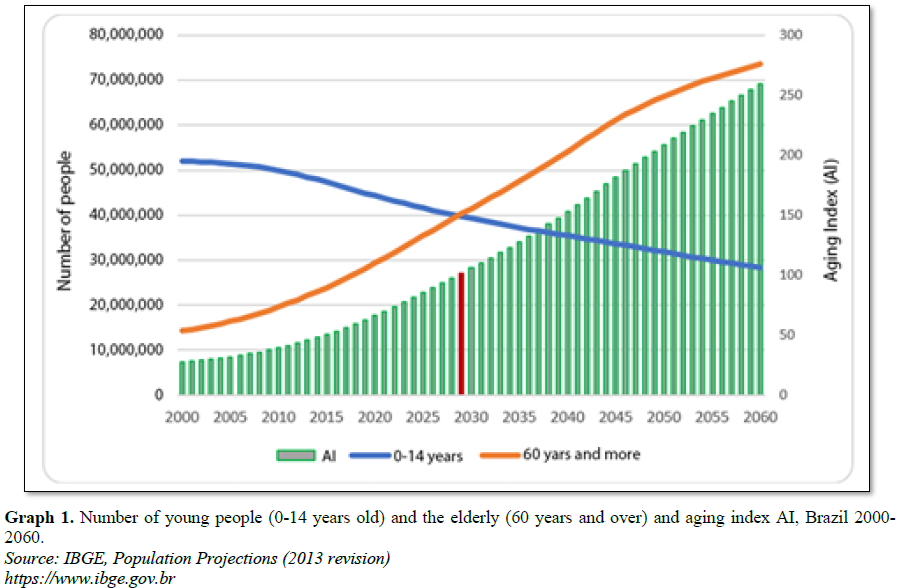

The demographic

projection for the next few years predicts further population aging. The

current scenario, therefore, is likely to worsen if the model remains

unchanged. Increased longevity leads to greater use of health services,

generating higher costs and demands on resources and threatening the

sustainability of the system. The chronic and multiple diseases that this group

suffers require constant monitoring, permanent care, continuous medication and

periodic examinations [5,6]. Our care models date from a time when Brazil was a

country of young people and acute diseases. Today, however, we are a young

country with grey hair. Actions based on health promotion and education, the

prevention and delay of the onset of diseases and frailties, and the

maintenance of independence and autonomy must be expanded [7,8].

HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS AND THE ELDERLY

In health systems

outside Brazil, general practitioners or family doctors are entirely

responsible for the treatment of 85% to 90% of their patients, without the need

for referral to specialists. Health professionals with specific training (in

Nutrition, Physical Therapy or Psychology) are also involved in care. In this

way, the elderly will have a much wider range of qualified professionals,

recommended to them by their own doctor [9].

In Brazil, however,

there is an excess of specialist consultations, with the current model

prioritizing the fragmentation of care. This can be clearly seen in comparisons

with the UK model, the National Health Service (NHS). Here, the central figure

is the general practitioner (GP), who has a high resolutive capacity and can

establish a strong bond with patients. The NHS is available to every citizen,

regardless of income or social status, in a similar manner to the SUS in

Brazil. To be eligible for free public health care, a citizen must register

with a General Practitioner (GP). The main health service units are local

clinics made up of general practitioners and nurses. Any medical care required,

provided it is not an emergency or caused by an accident, will be performed by

the health center doctor.

In contrast, the

American model is based around referral to numerous medical specialists,

resulting in a model of care that is the opposite to that of the UK. These two

rich countries, with great medical traditions, therefore employ different models

and achieve quite different results [10].

A contemporary

elderly healthcare model should employ a flow of actions based on education,

health promotion, the prevention of disease where possible, delayed onset of

illness, early care and rehabilitation from diseases. A care pathway for the

elderly based on efficacy and efficiency must presuppose an articulated,

referenced network with an information system based on this approach [11].

Health systems

currently operate with a small number of non-integrated points of care.

Patients generally enter this disjointed network at an advanced stage, with the

hospital emergency room often the entry point. Such a model, as well as being

inadequate and anachronistic, offers a very poor cost-benefit ratio, being

hospital-centered and involving intensive use of expensive technologies. Its

failure, however, should not be attributed to users, but to the care model

itself, with an overburdening at more complex levels of care due to a lack of

resolutive treatment at earlier levels.

One of the problems

faced by most current care models is an exclusive focus on disease. Even when a

program based on anticipating illness is offered, the proposals are primarily

geared towards the reduction of a certain disease. This overlooks the fact that

when a chronic disease is established the objective should not be a cure, but

stabilizing the clinical picture and constant monitoring to prevent or

ameliorate functional decline [12].

Studies have shown

that care must be organized in an integrated manner and should be coordinated

throughout its duration in a logic-based network, from entry into the system to

end of life care. New models of healthcare for the elderly should therefore

present a proposal for a care pathway that focuses on actions of education,

health promotion, the prevention of diseases where possible, delaying the onset

of disease, early care and rehabilitation.

Financial pressure

Demographic

transitions and the improvement in Brazil's social and economic indicators,

when compared with previous decades, have led not only to the growth of the

elderly population, but also to greater financial pressure on public and

private health systems. As the number of elderly people increases, so,

naturally, does the prevalence of chronic diseases and spending [8].

In recent decades

it has been seen that most of the public health problems that affect the

population – both communicable and non-communicable diseases – can be

prevented. This is demonstrated by a significant decrease in mortality from coronary

and cerebrovascular diseases and a reduction in the incidence of and mortality

from cervical cancer, as well as a decline in the prevalence of smoking and the

occurrence of lung cancer in men. A major social and economic burden can

therefore be avoided through the reduction of disease [13].

Many still see

preventative action as a burden of additional procedures and costs. In fact it

is the inverse of such thinking and, in the medium and long term, can reduce

hospitalizations and other, much more expensive procedures. All the evidence

indicates that biomedical health systems are likely to suffer problems of

sustainability in the future.

We live in the

information age. In the Collective Health field, epidemiological information

can be translated into a capacity to predict events, enabling early diagnosis,

especially in relation to chronic diseases. It can delay the onset of such

illnesses, improving quality of life and the effectiveness of the therapeutic

approach [10].

The model we

propose is based on the early identification of the risks of frailty among

users. Once risk is identified, the priority is early rehabilitation in order

to reduce the impact of chronic conditions on functionality, seeking to

intervene before harmful effects can occur. The idea is to monitor health, not

disease, with the intention of delaying the onset of illness so that the

elderly can enjoy the time they have left. Thus, the best strategy for the

proper care of the elderly is based on the permanent monitoring of health and

keeping such individuals under continuous observation, varying only the level,

intensity and context of the intervention [14].

The role of the

health professional in these cases is not to avoid the disease (as it is

already settled) or seek a cure, but to stabilize and reduce harm, aimed at

maintaining quality of life and preventing or mitigating functional decline

[15]. In general terms, these are the foundations of the healthcare proposed by

the Caring Senior program.

AN INNOVATIVE HEALTHCARE MODEL

Elderly care should

be structured in a unique manner. The current provision of health services

fragments care for this age group, with multiple specialist consultations, a

failure to share information, the widespread use of drugs, clinical and imaging

exams, and other procedures that overwhelm the system, have a major financial

impact at all levels and do not generate significant benefits for health or

quality of life [5]. As stated above, one of the problems stems from the

exclusive focus on disease.

The hierarchy of

the network provides at least two fundamental benefits for the care of the

elderly: reduced iatrogeny and more organized flow of care. Clinical guidelines

and protocols are also essential for the construction of the treatment plan.

They should direct good practices, be based on the best evidence available and

be appropriate for each clinical situation. The treatment plan guides the care

pathway according to the needs of the patient [14].

Programs aimed at

this group should be based on integrated care, with the key health professional

and his or her team managing not the disease, but the health profile of the

patient. Often, a health problem can only be treated with the reduction or

suspension of other actions [16]. Prevention is essential. The earlier an

intervention is carried out, the better the chances of a more positive

prognosis [9]. A health unit with a wider range of characteristics allows the

anticipation of problems through the early identification of possible symptoms,

changes in mood or possible functional loss. In this way, the elderly

individual can be referred promptly to their attending doctor [15].

A phrase which has

been repeated for decades in medicine is that the more a healthcare

professional knows about the history of their patient, the more positive the

results will be. This belief is supported by the World Health Organization and

all managers and professionals in the field of health. As logical as it is old,

it continues to represent a modern idea of a health care model [13]. It is

surprising, then, that we do not see it practiced on a daily basis. There

should be an emphasis on the integrated care of the elderly, adding

conventional medical care to the development of supervised educational and

leisure activities. The purpose is to maintain a good quality of life for as

long as possible.

The hospital is

often seen as the ideal location for healing. This, however, is a conceptual

error. Instead, the model should include several care settings prior to the

hospital, and hospitalization should occur only at the acute moment of chronic

illness or in cases of emergency, and should be as brief as possible. The entry

point to the system should be somewhere that allows the client and their family

to feel protected and supported. It is in this setting of first contact that

the user is informed of all the care possibilities and pathways available to

them. The reception phase is fundamental for those entering the system, and is

a stimulus for developing trust and fidelity.

The proposal of care

for the elderly should be understood as a strategy for establishing care

pathways, organizing the movement of individuals through the system according

to their degree of frailty. The identification of risk and the integrality of

care at the different points of the network are key to this model.

Hierarchization does not presuppose an evolutionary path between the care

levels of the model, although expected patterns can be anticipated. The stages

cannot be absolutely fixed, however, as there is always the possibility of

reverting disability and returning to less complex levels of care, depending on

each individual situation.

Better care results

and economic-financial outcomes are needed. To achieve this, everyone involved

in the model should understand the need for change and allow themselves to

innovate – in the care they provide, in the remuneration of the model, and in

the evaluation of the quality of the sector. Innovation often means recovering

the simplest forms of care and values that have been lost within our health

system.

The main risk

factor of most of the chronic diseases that affect the elderly individual is

age itself. Aging without chronic illnesses is the exception rather than the

rule. Thus, the focus of any contemporary policy should be to promote healthy

aging, by maintaining and improving – where possible – the functional capacity

of the elderly, the prevention of diseases, the recovery of the health of those

who have become sick (or the stabilization of illnesses) and the rehabilitation

of those who have had their functional capacity restricted. Actions such as

these, however, are still rare. The greatest investment continues to be in

traditional care, with emphasis on the hospital structure [4].

To say that

monitoring health and anticipating predictable illnesses is a "different

and innovative" way of caring questions the efficiency of healthcare

managers. Ideally, health care services should focus on providing qualified

care and well-being for the elderly, ensuring their clients have a referral

doctor, and that all doctors have a portfolio of clients for whom they provide

care. The care unit space should have the characteristics of a social center,

with a variety of activities including medical consultations and actions aimed

at integration and participation, encouraging the establishing of trust and

client loyalty within the model. This “innovation” is at least 70 years old, as

it has operated in the UK since 1948. It is nonsensical to consider it new. The

model proposed here, which we will call Caring

Senior, embraces the successful British experience and offers permanent

monitoring of health.

Our proposal: The caring senior model

To put these

theories into practice, the model of care for the elderly in Brazil must be

urgently redesigned [17]. The Caring Senior model was designed with these basic

assumptions in mind, and is characterized by a focus on low-intensity instances

of care, through the constant monitoring of the elderly and the provision of

light, but intensive care, as it is known that when properly monitored, more

than 85% of such clients do not require more complex care.

Other healthcare

actions will be the responsibility of a separate structure, which is

responsible for dealing with segments such as the emergency unit, the hospital,

clinical and imaging exams and medical specialists. Caring Senior will involve

specialist doctors and will also accompany its clients in high-intensity

instances of care – but as a support mechanism, not as a central element of

care, as we will see below.

Four aspects

underlie the entry point (or level 1) of Caring Senior: reception, fidelity,

integrality and assessment of the risk of frailty/ disability. Within this

model, levels 1 to 3 are low-intensity settings, or in other words involve

lower costs and are largely composed of care provided by well-trained health

professionals. Efforts should be made to maintain patients at such

low-intensity levels of care to preserve their quality of life and social

engagement [18]. The other settings, which involve more serious cases, are

expensive and include hospitals and other long stay facilities. Within these

settings, the preference is to rehabilitate the patient and transfer them to

low intensity settings, although this will not always be possible. Efforts

should be made to maintain the elderly within the first three levels of care,

to preserve quality of life and reduce costs. The goal is to concentrate more

than 90% of the elderly in these settings [19].

Care models for

this age group should be people-centered, based on the specific needs of

individuals. Care should be managed from the moment of entering the system to

the end of life, with constant monitoring. We know that the elderly face

specific challenges due to chronic diseases and the bodily and social frailties

they suffer [8]. Entering the model through Level 1 (reception) guarantees

conscious access to the system, a start based on transparency of the rules of

the healthcare plan, grace periods, rights and obligations, the care offered,

and bonuses and rewards. It is, therefore, the entry point, a crucial moment

for establishing empathy and trust, fundamental elements of user fidelity.

Another important

differential is the proposal to register the care pathways of patients through

a comprehensive information system, which will record not only the clinical

evolution of the elderly persons, but also their participation in individual or

collective preventative actions, as well as interaction with the care support

manager and phone calls made to or by the “GerontoLine” (the name we have given

to a qualified and resolutive call-center) or use of computer or smart phone

apps. This allows the sharing of information, enabling a more complete

evaluation of the individual and including the medical records of the hospital

unit, governed by specific norms.

Caring Senior is

based on certain principles. The first is the role of the doctor, who is

responsible for a portfolio of clients. A nurse will also be available, and

will perform an effective role in providing care to the clientele and ensuring

better quality of care. The clinical unit will have several such pairs of

general practitioners and nurses, and a 40-hour work week will allow for

portfolios that can provide care to between 800 and 1,000 clients. This will

guarantee that healthcare professionals have the time to attend each client

properly, ensuring appointments at least four times a year, and accompanying

them in other instances of care, if necessary.

A full Caring

Senior unit, for example, will have five pairs of doctors and nurses who are

responsible for around 4,000 to 5,000 patients. Health professionals must be

trained to provide care within the philosophy of the program, prioritizing

health promotion and disease prevention. These will include psychologists,

nutritionists, physiotherapists and physical educators, who will attend cases

as selected by doctors. These professionals will lead group activities and

lectures and provide guidance on relevant topics. In addition, each region

(depending of course on demand) will have two or three minimum capacity units,

featuring only a doctor/nurse pair, with support services provided in the full

unit.

To allay fears

about the possible high costs of maintaining such a structure, it is worth

noting that health professionals cost much less than a day's stay in an

Intensive Care Unit or hospital. To provide good care and avoid the exaggerated

use of specialist doctors and unnecessary hospitalizations, it is essential to

maintain a high quality reception structure.

This relationship

between the healthcare system and the user must change. It should be

transparent, establishing a pact based on truth. The actions performed must be

recorded in the information system, which must begin at reception and continue

until the end of the patient's life [20].

The hierarchy of

the care model provides knowledge of its users, their profile and their needs,

in order to better organize the delivery of services. One thing is certain:

without better organization of the care of the elderly and the elaboration of a

care plan, population aging and the greater prevalence of diseases will cease

to be opportunities, and will instead become obstacles for the sustainability

of the Brazilian supplementary health system.

It is important to

emphasize that the proposal presented herein is not only intended to discuss

mechanisms for the reduction of health costs, which, while important, is not

the only concern. Like the other issues, it drives us towards a greater goal,

namely the integral care of the elderly. The model presented has a commitment

and goal of improving the quality and coordination of the care provided from

the entry point to the system and throughout the continuum of care, avoiding

redundant examinations and prescriptions, interruptions in the health

trajectory of the user and iatrogeny generated by the disarticulation of health

interventions.

The hospital and

the emergency room will always be important settings for the provision of

health care, but it is necessary to redefine and recreate the roles they play

in today’s health care network. These units of care should be reserved

primarily for moments of acute chronic illness [21].

An adult client

aged over 49, with one or more chronic diseases will not be cured. The duty of

the physician is to stabilize, monitor, and ease the pain caused by the

disease, which is likely to remain with the patient for the rest of their

lives. The role of the Caring Senior general practitioner will be to maintain

the functional capacity of clients so that they can enjoy a full and healthy

life. The benefit of Caring Senior will be the reduction of the numbers of

specialist doctors and subsequently fewer exams and drugs, as loyalty will

prevent the client from resorting to emergency units and so greatly reduce

hospitalization periods.

It should be

remembered that Caring Senior involves low-intensity instances of care, and is

largely composed of care provided by well-trained health professionals

concerned with preserving the quality of life and social participation of their

elderly clients. Instances considered high-intensity are expensive and involve

the hospital and other long stay units. All effort must be taken to

rehabilitate the elderly and return them to low-intensity instances of care.

Central points of the model

Three aspects must

be considered, namely:

1.

The doctor and

nurse are responsible for a portfolio of clients.

2.

The user will

receive a financial stimulus (reward) for adherence to the care model, which is

based on monitoring and fidelity to the health team.

3.

The

remuneration of the physician and the health team will be established through

the success of the care. Better performance results in better rewards. It is

acknowledged that health professionals are poorly paid.

The quality of care

offered by the attending physician, his or her client portfolio and his or her

variable remuneration are of similar importance. Emphasis is also placed on the

client portfolio, functional assessments, the tracking of risks, the work of

the care support manager, and an efficient information system that records all

client events. The importance of the various care settings, such as the

outpatient clinic, the hospital, home care, rehabilitation, the

multidisciplinary team, the cohabitation center and palliative care, should

also be highlighted. All are part of the network of care and are integrated

through the information system and the attending physician, who remains the

clinical reference throughout the course of the model. It is clear that the

hospital is only one setting. It is equal to the others, but less important

than preventive actions, which are the center of the model. The logic is based

on low-intensity settings and integral care, the multidisciplinary team and the

doctor responsible for the patient.

For the model to

succeed, therefore, it is essential that clients are encouraged to participate

in the proposed programs and actions, instead of the current logic of using a

health plan only when undergoing tests or going to hospital with a disease

already in an advanced stage. The model includes all possible care settings,

excludes nothing in relation to the care required – in fact, it includes new

units not usually offered to the clients of many healthcare providers – and

prioritizes the provision of care in “lower intensity" settings. These

offer the best possible care, with trained and qualified professionals, based

on modern scientific conceptions of treatment. In short, our proposal is to

invest in health to reduce spending on disease.

A high quality,

easy to use technology information system will provide fundamental support for

the doctor/nurse pairing and facilitate client loyalty. Technology is an

essential part of the Caring Senior project, and so participants must be able

to use the system to its maximum potential.

For example, the

faces of clients could be recognized when they come through the door of the

clinic, allowing their medical records to be open on the receptionist’s desk by

the time they get there. The receptionists can then address the clients by

name, ask about their families, and check the list of medications they are

taking. These simple actions add enormous trust to the relationship, making the

client feel protected and welcomed from the first instance.

Registering the

care pathways of the patient is a unique feature of this model. A high-quality

information system of broad scope can document not only the clinical evolution

of the elderly person, but also their participation in individual or collective

prevention actions, as well as the support provided by the nurse and telephone

calls made, all of which must be resolutive and performed by trained and qualified

personnel.

Information from

telephone, computer or cell phone contact between patients and professionals

should be shared among the team, to enable a comprehensive assessment of the

individual. The information system, which begins with the registration of the

client, is one of the pillars of the program. It allows the entire care pathway

to be monitored at each level, verifying the effectiveness of the actions and

contributing to decision-making and follow-up care. It is a unique electronic

record, which is both longitudinal and involves a range of professionals, and

accompanies clients from reception onwards. This medical record differs from

existing registries as it includes a record of their life history and health

events.

The creation of a

mobile app with individualized information and reminders of consultations and

prescribed actions is also planned. This can, among other actions, ask the

client to take a photo of their breakfast and send it to the nutritionist, who

will observe if the meal is balanced and if there are adequate amounts of

fiber, for example.

Caring Senior will

focus on keeping its clients within its units, avoiding the use of specialists.

However, five areas of medical specialties related to our model will be

required to assist the general practitioner – cardiology, gynecology,

urology-proctology, dermatology and ophthalmology. These are chosen based on

demand and high prevalence, and include areas where annual preventive control

examinations can be carried out and registered.

Consultation with

the specialties listed will only be possible at the request of the general

practitioner of the client. If they require the care of one specialist, Caring

Senior will not necessarily include the other specialties. The same reasoning

applies to hospitalization. Doctors and nurses will be responsible for

contacting the hospital doctor, armed with knowledge of the case and,

preferably acting to ensure the best care and the briefest period of

hospitalization, as well as being able, if necessary, to suggest a medical

specialist.

Another key element

of Caring Senior is the form of payment of physicians, the Accountable Care

Organization (ACO) system, which encourages healthcare professionals to

organize themselves as a group, managing the quality of services provided,

being responsible for cost management and the distribution of bonuses [22].

There are two key

points: the provision of services of excellence at a lower cost and a model of

remuneration based on added value. The segmented and non-integrated healthcare

that is offered to patients today is largely due to the service remuneration

model, in which the incentive is production, rather than quality [23]. In other

words, there is no benefit in seeking new forms of care or new payment models

if transferring part of the responsibilities, risks and benefits of providers

is not associated with the results achieved through the care provided. The

challenge is to make this new care model acceptable to the client, since trust

(which will lead to loyalty) is an indispensable factor if the process is to

function as planned. One cannot, after all, ask a person to trust something

they do not understand.

Simply stating that

Caring Senior is the best model is irrelevant, however, if it is not applied by

Brazilian supplementary health services. Society needs to be made fully aware

of the proposal if it is to become convinced of its benefits [6]. Otherwise,

healthcare will continue to opt for the “siren song” of excess and consumption,

which burden the system, generate higher costs, and render long-term care

unfeasible.

FINAL REMARKS

The desire for a

higher quality and more effective elderly care model is not solely a Brazilian

concern. The entire world is debating this issue, recognizing the need for

change and proposing improvements in their health systems [33].

There is no single

model, but instead a multi-faceted approach that favors low-intensity care,

constant monitoring, an efficient telephone service and the use of mobile apps,

a doctor responsible for a portfolio of clients who then accompanies them

through all the care settings, a nurse who works in partnership with the

doctor, teamwork, the use of epidemiological tools to monitor functionality,

and a quality electronic medical record. All these elements contrast with the

model based around specialist doctors, the disarticulation of professionals,

the prioritization of use of the hospital, the excessive consumption of drugs

and an overuse of laboratory and image exams [25].

There are a number

of suggestions for care pathway models. The important thing is for each health

institution to be aware of its users, their profile and their needs, to

construct the best way of organizing the delivery of its service. One thing is

certain – without the organization of elderly care and the elaboration of a

care plan, population aging and the increased prevalence of chronic diseases in

the public or supplementary health sector in Brazil may no longer be seen as

opportunities, but instead become obstacles to the sustainability of the

system.

The socioeconomic

transformations of recent decades and the consequent alterations in the

lifestyles of individuals in contemporary societies – with changes in eating

habits, increased sedentarism and stress, plus the greater life expectancy of

the population – have contributed to a higher incidence of chronic diseases,

something that today represents a serious public health problem.

The current

provision of health services fragments care for the elderly. It overburdens the

system, causes a serious financial impact at all levels and does not generate

significant benefits for quality of life. It is therefore imperative that a new

model is adopted. If we know the population is older, that diseases are chronic

and multiple, that the costs of care are increasing, that the models of care

are from an era of acute diseases and that a knowledge of epidemiology can

inform us of risk factors, why do we continue to offer an outdated and

ineffective product? Especially if we have all the information required to

implement an assistance-based care model in which everyone benefits?

It is necessary to

rethink and redesign care for the elderly, turning the focus towards the

individual and their particularities. This will bring benefits not only to this

part of the population, but also quality and sustainability to the entire

Brazilian health system.

We believe that it

is possible to grow old with health and a good quality of life, provided that

all the actors in the sector see themselves as responsible for the necessary

changes and allow themselves to innovate through improvements in care, in forms

of remuneration and in evaluating the quality of the sector [26].

Elderly persons,

because of their greater vulnerability and greater use of the health system,

are among the most affected by the current care model.

As Don Berwick [27]

wrote in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) – “Every health system

is perfectly designed to achieve the results it achieves”. Our health system

has achieved a demographic transition (aging), an epidemiological transition

(we now have a triple burden of diseases), a nutritional transition (we have

moved from malnutrition to obesity), but we have not been able to make the

much-needed transition in our health institutions, which remain organized to

treat acute, infectious diseases [28]. Some elements are necessary if a system

is to change health outcomes, such as evaluation and remuneration based on

quality and an information system that can facilitate the care pathway of the

patient.

It is possible to

reorient the healthcare of the elderly population and to construct an

organization within this sector that provides greater well-being and better

economic-financial results. To achieve this, everyone involved must realize

they are responsible for the changes required and allow themselves to innovate

– which, in many situations, means recovering the simpler care and values that

have been lost within our health system.

The entire model

proposes a reorganization of care that has already been shown to be much more

effective and cheaper for the health system. It simply means doing what is

necessary, in the right way, focusing on the most important element of every

process, which is the patient.

Another key point

is the participation of the elderly person in the model, using strategies that

can help to convince these individuals of the importance of preventive care,

such as the rewards offered by health plans.

1. Abicalaffe CL (2011) Pagamento por

performance: O desafio de avaliar o desempenho na área da saúde. J Bras Econ

Saúde 3: 179-185.

2. Banco M (2011) Envelhecendo Em Um

Brasil Mais Velho. Washington Dc: World Bank

3. Berwick DM (2011) Launching

accountable care organizations: The proposed rule for the medicare shared

savings program. N Engl J Med 364: 32.

4. Berwick DM (2011) Making good on

Acos’ promise: The final rule for the medicare shared savings program. N Engl J

Med 365: 1753-1756.

5. Box G (2016) Understanding and

responding to demand in English general practice. Br J Gen Pract 66: 456-457.

6. Brasil (2013) Agência Nacional De

Saúde Suplementar. Plano De Cuidado Para Idosos Na Saúde Suplementar. Rio De

Janeiro: Ans.

7. Brasil (2006) Ministério Da Saúde.

Portaria Nº. 2.528, 19 De Outubro De 2006. Aprova A Política Nacional De Saúde

Da Pessoa Idosa. Brasília, Df: Ministério Da Saúde.

8. Caldas CP, Veras RP, da Motta LB

(2015) Atendimento De Emergência E Suas Interfaces: O Cuidado De Curta Duração

A Idosos. J Bras Econ Saúde 7: 62-69.

9. Carvalho VKS, Marques CP, Silva EN

(2016) Contribuição Do Programa Mais Médicos: Análise A Partir Das

Recomendações Da Oms Para Provimento De Médicos. Ciênc Saúde Colet 21:

2773-2784.

10. Closs E, Schwnake Cha. A (2012)

Evolução Do Índice De Envelhecimento No Brasil, Nas Suas Regiões E Unidades

Federativas No Período De 1970 A 2010. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 15: 443-458.

11. de Lima KC, Caldas CP, Veras RP

(2016) Health promotion and education: A study of the effectiveness of programs

focusing on the aging process. Int J Health Serv.

12. Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia

E Estatística (Ibge). Population Projections. Rio De Janeiro: Ibge, 2013.

Available at: https://www.ibge.gov.br/apps/populacao/projecao/ Access: 12 May 2019.

13. Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia

E Estatística (Ibge). Indicadores Sociais. Rio De Janeiro: Ibge, 2018.

Available at: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/17270-pnad-continua.html?t=series-hist%25c3%25b3ricas Access: 12 May 2019.

14. Lima-Costa MF, Veras RP (2003)

Saúde Pública E Envelhecimento [Editorial]. Cad Saúde Pública 19: 700-701.

15. Médici A, Abicalaffe C, Tavares L

(2018) Pagamento Por Performance. Empreender Saúde; 2015. Disponível Em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281642162_pagamento_por_performance_em_saude#pf3 Access: May 17.

16. Mendes EV (2011) As Redes De

Atenção À Saúde. Brasília, Df: Opas.

17. Minayo MCS, Firmo JOA (2019)

Longevidade: Bônus Ou Ônus? Editorial. Ciênc. Saúde Colet 24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018241.31212018

18. Moraes EN (2012) Atenção À Saúde

Do Idoso: Aspectos Conceituais. Brasília: Organização. Pan-Americana Da

Saúde.

19. Oliveira M, Veras RP, Cordeiro HA

(2017) Saúde Suplementar E O Envelhecimento Após 19 Anos De Regulação: Onde

Estamos? Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 20: 624-633.

20. Oliveira M, Veras RP (2015) Um

Modelo Eficiente No Cuidado À Pessoa Idosa. Correio Brasiliense 27: 13.

21. Oliveira MR, Silveira DP, Neves R

(2016) Idoso Na Saúde Suplementar: Uma Urgência Para A Saúde Da Sociedade E

Para A Sustentabilidade Do Setor. Rio De Janeiro: Ans.

22. Oliveira MR, Veras RP, Cordeiro HA

(2016) A Mudança De Modelo Assistencial De Cuidado Ao Idoso Na Saúde

Suplementar: Identificação De Seus Pontos-Chave E Obstáculos Para

Implementação. Physis: Revista De Saúde Coletiva 26: 1383-1394.

23. Silva AMM, Mambrini JVM, Peixoto

SV (2017) Uso De Serviços De Saúde Por Idosos Brasileiros Com E Sem Limitação

Funcional. Rev Saúde Pública 51: 1-10.

24. Szwarcwald CL, Damacena GN, Souza

Júnior PRB (2016) Percepção Da População Brasileira Sobre A Assistência

Prestada Pelo Médico. Cienc Saúde Colet 21: 339-350.

25. Veras RP, Amorim AE (2015)

Relatório Final Unati/ Uerj: Projeto: Modelo De Hierarquização Da Atenção Ao

Idoso Com Base Na Complexidade Dos Cuidados: Proposta De Monitoramento Dos Três

Níveis De Cuidado Na Assistência Suplementar. Rio De Janeiro Contrato

Br/Cnt/1401445.001.

26. Veras RP, Caldas CP, Cordeiro HA

(2013) Desenvolvimento De Uma Linha De Cuidados Para O Idoso: Hierarquização Da

Atenção Baseada Na Capacidade Funcional. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 16: 385-392.

27. Veras RP, Caldas CP, Cordeiro HA

(2013) Modelos De Atenção À Saúde Do Idoso: Repensando O Sentido Da Prevenção

Physis: Revista De Saúde Coletiva 23: 1189-1213.

28. Veras RP, Caldas CP, Motta LB

(2014) Integração E Continuidade Do Cuidado Em Modelos De Rede De Atenção À Saúde

Para Idosos Frágeis. Rev Saúde Pública 48: 357-365.

29. Veras RP, Estevam A (2015)Modelo

De Atenção À Saúde Do Idoso: Ênfase Sobre O Primeiro Nível De Atenção. In:

Lozer AC, Godoy CVC, Leles FAG, (Eds.). Conhecimento Técnico-Científico Para

Qualificação Da Saúde Suplementar. Brasília, Df: Opas/Ans, pp: 73-84.

30. Veras RP, Lima-Costa MF (2011)

Epidemiologia Do Envelhecimento. In: De Almeida Filho N, Barreto Ml.

Epidemiologia E Saúde: Fundamentos, Métodos, Aplicações. Rio De Janeiro:

Guanabara Koogan, pp: 427-437.

31. Veras RP, Oliveira M (2018)

Envelhecer No Brasil: A Construção De Um Modelo De Cuidado. Ciênc Saúde Colet

23: 1929-1936.

32. Veras RP, Oliveira MR (2016) Linha

De Cuidado Para O Idoso: Detalhando O Modelo. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 19:

887-905.

33. Veras RP (2011) A Necessária

Gestão Qualificada Na Área Da Saúde: Decorrência Da Ampliação Do Segmento

Etário Dos Idosos. J Bras Econ Saúde 3: 31-39.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Archive of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine (ISSN:2640-2297)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

- Chemotherapy Research Journal (ISSN:2642-0236)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Journal of Nursing and Occupational Health (ISSN: 2640-0845)