2600

Views & Citations1600

Likes & Shares

Globally, there are approximately 36.7 million people living with HIV, with an estimated 3.8 million individuals newly infected with HIV and about 5,000 new infections per day in the year 2017-2018. Integration of HIV treatment with primary care services improves effectiveness, efficiency and equity in service delivery. In Embu teaching and referral hospital, integration of HIV services with other primary health services were initiated in 2014 and up to date, the integration has not been fully adopted by the clients therefore, the study sought to establish the perception of seropositive clients on integrated HIV and primary health care services in Embu Teaching and Referral hospital. A cross sectional survey design was used to collect data from a sample of 312 seropositive clients who were selected using simple random method. A structured and semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data while key informant interviews (KII) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) helped to collect qualitative data. The tools were reliable at Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7. SPSS version 25 was used to analyze the data. A binary logistic regression model was used to predict the effect of determinants of utilization of integrated HIV services and primary health care services.

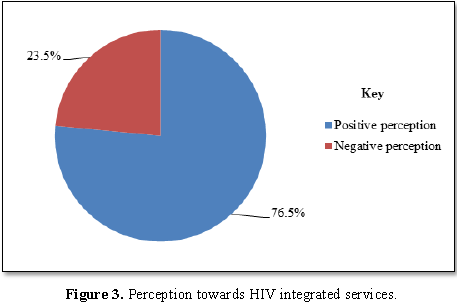

Results: Majority of the respondents (59.6%) were aged over 35 years with majority being female (58.9%) and the married were 57.6% of the total sample. On perception on integrated services 76.5% had a positive perception.

Conclusion: Majority of the clients had a positive perception towards the integrated service. They perceived the staff attitude as positive and acknowledged that integration allowed them opportunities to share their life experiences. However, they felt there was need to increase services provided under the integrated arrangement such as cancer screening, TB clinics and other services such as blood pressure monitoring.

Recommendation: The Government of Kenya through the Ministry of Health should engage the county government and support from NGO`s to come up with structures and resources needed to expand the facility in terms of facility space and incorporation of other primary health care services like cancer screening, diabetes screening, dental and ophthalmology services.

Keywords: Perception, Integrated services, Embu teaching and referral hospital, HIV patients, Primary health care services

INTRODUCTION

Globally, there are approximately 36.7 million people living with HIV in the year 2017-2018, with an estimated 3.8 million individuals newly infected with HIV and about 5,000 new infections per day [1]. Among these people 2.1 million are children and teenagers below 15 years of age, most of them from sub Saharan Africa. The vast majority of people living with HIV are in low- and middle-income countries. In 2017, there were 19.6 million people living with HIV (53%) in eastern and southern Africa, 6.1 million (16%) in western and central Africa, 5.2 million (14%) in Asia and the Pacific, and 2.2 million (6%) in Western and Central Europe and North America. Despite implementing some of the preventive measures many people living with HIV or at risk for HIV still do not have access to proper care and treatment [1]. Efforts have been made by the global community to prevent HIV and treat related illnesses. However too many people with or at risk of contracting HIV have no access to care, treatment and prevention [1]. Nevertheless, global goal achievement of zero new HIV infections, zero AIDS related deaths and zero discrimination has been achieved in most developed countries. In Asia and pacific region remarkable progress has been made as indicated by 26% decline in new HIV infections from 2001-2012 and a 46% increase in access to Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) from 2009 to 2012 [2]. Majority of developing countries need more time to achieve the zero new HIV infections goal. They need to be more innovative in treatment, prevention and putting up more programs to be able to achieve the overall goal. Some of the pillars have been put in place to achieve this goal and one of the pillars is to adapt delivery systems. This entails decentralisation and integration of HIV care and treatment with other HIV and non-HIV services such as drug dependency services, maternal, new-born and child health or Tuberculosis services. The primary aim of this pillar is to increase community engagement for HIV testing and counseling, care retention and early initiation of ART [2].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, integration of HIV and family planning services has been shown to have several benefits [3]. These includes services rendered are affordable to clients, reduction of stigma and discrimination. Other studies conducted in South Africa on perception of integration of HIV and sexual reproductive health care, suggested a preference for integrated care among female clients, particularly because of stigma reduction and higher access to contraceptives [4]. Some of the perception of clinicians and clients on integration of primary health care and HIV services showed that about 80% of the respondents were satisfied with integration because the organization of services and confidentiality prevented stigma and discrimination. Majority of participants in the fully and partially integrated facilities reported that clinicians treated them with respect, privacy and confidentiality. Other participants referred staffs as rude and unfriendly, increased waiting time before one is attended to, interruption of consultation which was seen as infringement of privacy. Similar study showed that clients felt that there were delays related to lack of punctuality to report on duty after lunch and tea break, poor staff communication regarding delays in patients consultations like when they break for lunch the staffs do not communicate to the clients [5].

Majority of the respondents in a study conducted in Ethiopia reported positive feelings towards the disease and therefore can disclose their status to their families comfortably and 50% of the respondents mentioned that TB carry the same stigma as HIV, this kind of stigma is reduced when integration of services is embraced [6]. Integration of HIV services and TB treatment demonstrated relative success of integrated and co-located TB/HIV services in Swaziland and revealed timely ART uptake for HIV-positive TB patients in resource-limited, but integrated settings [7].

A research carried out on patient’s perception on HIV treatment integration with other services reported that most clients were satisfied with integration of services [8]. However, the clients reported that the staffs’ attitude, number of staffs in health facilities and health care provider, patient communication were significantly affecting patients’ satisfaction levels. In Cameroon integration has led to increased utilization of HIV services, therefore when integration is implemented well and staffs’ attitude and communication improved; patient level of satisfaction was predicted to improve significantly [8].

In Kenya, a study done on experiences of health care providers with integrated HIV and reproductive health services revealed that more clients were satisfied and were willing to uptake HIV testing than in stand-alone clinics. It also revealed that with increased number of clients, infrastructural deficiencies hindered effective delivery of the services as well as limiting quality time for counseling of the patients due to shortage of staffs in relation to high numbers of in flowing clients [4]. Some providers reported that integration enhanced job satisfaction by providing a better quality service, which led to their receiving more regular positive feedback from clients. Collocation of HIV services and primary health care addresses the issue of scarce resource allocation, integration maximizes use of health facility structures and ensures that funds targeted for construction of HIV facilities will also benefit primary health care; therefore both patients can access health care regardless of their HIV status [9].

A recent review identified various discriminatory behaviors and negative attitude towards HIV patients. Some of the behaviors were denial of care and testing or status disclosure without consent, verbal abuse, additional fee and overuse of gloves especially health care providers on HIV patients. It has been speculated that stand alone HIV services may be stigmatizing, as clients are labeled as they walk through the door resulting in an involuntary disclosure of status. Other structural influences include avoidance or isolation of HIV clients and labeling of buildings and rooms [9]. Integration is also likely to reorganize health care delivery which may disrupt service provision and cause dissatisfaction among patients. Further integration of specialized services into primary care services may not always result in better patient and service level outcome for example integration of HIV services with sexual and reproductive health services may be hindered by increased patient burden, inadequate staffing and resistance from existing health care workers. Integrating services for STI into routine health services may result in lower utilization and reduced patient satisfaction [10].

In Embu County, HIV prevalence is at 3.3% according to Kenya HIV Estimates 2015.The County contributed 0.7% of the people living with HIV in Kenya, with women having a higher prevalence (4.5%) than that of men (2.0%). In a report released by Kenya Demographic Health Survey in 2014, it is evident that 36% of men and 16% of women in Embu County never sought HIV testing services; therefore the county needs more innovative strategies to improve on HIV testing and counseling, reduce HIV related stigma and promote client satisfaction towards HIV services, to bridge the unmet gaps [11].

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional descriptive survey design was used to generate both quantitative and qualitative data. This design was appropriate since the study was carried out at a specific point in time without any manipulation of the variables. The study population in this study was sero-positive HIV clients. A target population of 1650 clients was applied as per the comprehensive care clinic register; approximately 55 clients per day receive HIV services, a sample of 312 respondents was used in the study. They were appropriate for this study because they are informed about integration and they are the main beneficiaries of these services. Reliability of the tool was tested and the Cronbach’s alpha was calculated and was found to be at (p=0.817) which showed a high degree of reliability of the variables.

Quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS version 25 and thematic analysis was done for qualitative data using N-Vivo version 11. A simple logistic regression model was fitted, to determine the set of significant variables for each of the dependent variables. Variable selection for the multivariable analysis was done dropping for all those covariates with a p-value >0.05 from the main analysis. The second stage of variable selection entailed forward selection coupled with the likelihood ratio tests. 5% level of significance was applied on all analyses.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics were divided into: non-illness related characteristics and illness related characteristics. Non-illness related characteristics included age, gender, marital status, religion and level of education. On the other hand, illness related characteristics included whether or not client was on ART, duration of ART, utilization of other services beside HIV care under one roof, whether one ever received medical care in the clinic, employment status, distance from home to the facility and services being currently sought at the clinic.

Table 1 show that 8.9% (27) of the respondents were aged 18-22 years, 8.6% (26) were aged between 23-26 years, 1.7% (5) of the respondents were aged 27-31 years, 21.2% (64) were aged between 32-35 years while those who were over 35 years constituted 59.6% (180).Majority, i.e., 98.7% (298) had received the combined HIV care and other services under one roof, while 1.3% (4) had not. Concerning duration of medical care in the clinic, 0.7% (2) had received care for less than 1 year, 27.8% (84) had received care for 1-2 years, and 26.8% (81) had received care for 3-5 years while 44.7% (135) had received care for more than 5 years.

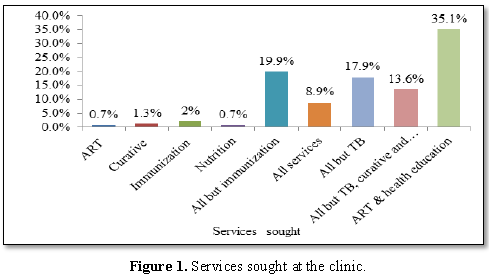

Figure 1 shows that most respondents, i.e., 35.1% (106) were seeking ART services and health education, while the services least sought after were immunization and curative services with 2% (6) and 1.3% (4), respectively.

HIV PATIENTS’ UTILIZATION OF INTEGRATED HIV AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE SERVICES

Utilization was assessed using a set of 5 practice questions from which results the status was either “utilization” or “non-utilization”. Utilization with regard to action taken when one experienced HIV related illnesses( practice question 1) meant, visiting the health facility immediately, utilization regarding appointments (practice question 2) meant not missing any appointment, utilization regarding drugs (practice question 3) meant not missing the prescribed drugs, utilization regarding conventional medicine (practice question 4) meant taking only prescribed medicine given at the clinic and utilization regarding consultations (practice question 5) meant consulting the health worker whenever in doubt.

Table 3 shows that 99.3% (300) of the respondents visited the health facility immediately whenever they experienced an illness related to HIV infection, while 0.7% (2) tried other measures at home. Majority, i.e., 66.9% (202) had ever missed appointment given in the course of care while 33.1% (100) had never missed any appointment. Most respondents, i.e., 77.8% (235) had never missed to take any drugs or treatment options given in the facility of care while 22.2% (67) had missed some treatment.Concerning use of alternative medicine outside conventional prescribed medical care, all the respondents were found to avoid such treatments. Likewise, all the respondents consulted the facility care provider whenever they had bothering questions about the care they were receiving. Utilization level was determined by the number of items that respondents utilized as recommended. Out of five items, those who utilized at least 4 out five were considered as utilizing integrated HIV and primary health care services while those who utilized below 4 were considered as not utilizing the services.

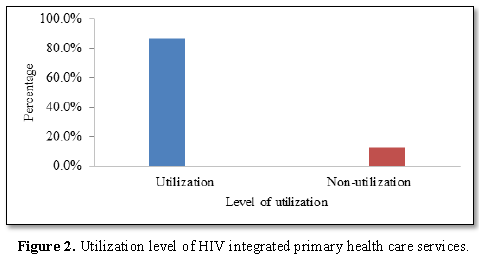

Figure 2 shows that majority of the respondents, i.e., 86.8% (262) utilized integrated HIV and primary health care services while 12.9% (39) did not.

PERCEPTIONS OF HIV PATIENTS ON INTEGRATED PRIMARY HEALTH CARE SERVICES

Perceptions were assessed through a set of 10 likert form statements where responses were “agree”, “disagree”, “strongly agree”, and “strongly disagree”. Three statements that had been negatively phrased were reverse coded before analysis. Those who either agreed or strongly agreed were considered as having a positive perception, while those who either disagreed or strongly disagreed were considered as having a negative perception. Positive perception implied that the patients were satisfied, while negative perception implied that the patients were not satisfied.

Table 4 Shows that most respondents either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” which was indicative of an overall positive perception.The researcher went ahead and computed a variable known as “perception score” in order to assess the perception statuses for individual respondents. The responses were coded as follows: Strongly agree=4, agree=3, disagree=2 and strongly disagree=1. The maximum one would score was 40 (4 × 10) and the lowest possible score was 10 (1 × 10). A score of at least 30 meant a positive perception and below that was meant a negative perception.

Figure 3 shows that 76.5% of the respondents had a positive perception of the services offered at the clinic while 23.5% had a negative perception. Positive perception was indicative of satisfaction while negative perception was indicative of dissatisfaction. Perceptions were cross-tabulated against utilization of integrated HIV and primary health care services.

Table 5 shows that there was no significant relationship between client perceptions and utilization of integrated HIV and primary health care services (χ2 (1, N=302) =2.486, p=0.092), therefore the null hypothesis that there is no statistically significant relationship between perception and utilization of HIV integrated primary health care services was accepted.

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS ON PERCEPTIONS

Qualitative data from focused group discussions and key informant questionnaire was analysed thematically and theme summaries were given under each theme. The emerging themes from focused group discussions were: staff attitude, sharing information with others, and availability of resources.

Staff attitude

The staff attitude was generally positive as perceived by the clients. Staffs were patient, nice, humble, understanding, polite and they gave undivided attention to the clients. They expressed readiness to attend to patients’ needs, by being good listeners which showed a caring and concerned attitude for patients. However, some staffs were a bit strict on late comers who ended up missing out on important services like health education and counseling. Someone narrated, “Staffs are very harsh when one comes to the clinic late. This is my body, am an adult and voluntarily came to the clinic to know my HIV status, l have been utilizing this services voluntarily, coming late once in a while is not one`s fault and no one should incriminate me if l fail to attend 8 a.m health talk sessions” (Focused group discussion respondent 4).

Some staffs also failed to recognise the patients in pain and appropriate pain management measures were ignored.

Sharing information with others

Patients shared on how drugs were affecting them. Old clients shared their experiences, patients learnt from each other, patients were able to interact and learn, some clients came from other facilities and shared their experiences, staffs also shared about their personal health and this motivated the patients a lot. There was a lot of sharing of experiences related to stigmatization.

Availability and use of resources

Clients felt that the waiting times needed to be reduced. More lab tests, e.g. cancer screening, pregnancy tests for youths, and blood sugar monitoring needed to be incorporated in the clinic to cover all illnesses even the minor ones. Multivitamin drugs needed to be availed all the time and health talks for patients who could not make it to come early in the morning, when health talks usually took place. More space needed to be availed for the waiting bay and more clinics built, e.g. chest clinic for TB patients.

The themes for key informant questionnaire were integrated services and utilization of integrated services.

Integrated services (key informant interview)

Integrated services meant getting a package of standardized care under one roof. The services were efficient in terms of saving time and space, thus, enabling clients get satisfaction of service offered. Challenges included lack of some essential services such as cervical cancer screening necessitating referral to other departments. There was limited space and clients waited outside the room for a certain service provider to attend to them. Support was needed from NGOS and county government in funding essential services missed out, in construction of more rooms and providing reagents and all consumables.

Utilization of integrated services

The services were accessible to clients easily enhancing more utilization by clients demanding for them e.g. partner testing. Integration of services led to job satisfaction in serving clients. Using the available resources, the health system had distributed and allocated funds and personnel to serve people living with HIV.

During focus group discussion, it was broadly argued that generally staff attitude was generally positive as perceived by the clients. Staffs were patient, nice, humble, understanding, polite and they gave undivided attention to the clients. However, some staffs were a bit strict on late comers who ended up missing out on important services like health education which took place at exactly 8.00am in the morning. This finding echoed what [4] found out that the clinicians could give the patient a listening hear, respect them irrespective of their status and could spend more time with the patient to their satisfaction. Similar study reported that clinicians treated the patients with respect, privacy and confidentiality other participants referred staffs as rude and unfriendly, as depicted in the finding. The findings also concurred with early research done in Kisumu, which reported that educative sessions, and positive staff attitude were of great significance especially in an integrated care program: this session’s increased patient’s satisfaction [10].

CONCLUSION

Majority of the clients had a positive perception towards the integrated service. They perceived the staff attitude as positive and acknowledged that integration allowed them opportunities to share their life experiences. However, they felt there was need to increase services provided under the integrated arrangement such as cancer screening, TB clinics and other services such as blood pressure monitoring.

RECOMMENDATION

i. The Government of Kenya through the Ministry of Health should engage the county government and support from NGO’s to come up with structures and resources needed in order to expand the facility in terms of facility space and incorporation of other primary health care services like cancer screening, diabetes screening, dental and ophthalmology services.

ii. The hospital administration should come up with strategies and avenues which will enable the clients to channel their complaints, dissatisfaction and grievances comfortably without fear. This will enable the health workers to know their weaknesses and even improve the services provided to the clients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

My Appreciation goes to my dedicated academic supervisors, Dr. Moses Muraya and to Dr. Micah Matiang`i for the untiring technical and moral support provided throughout the study process. Exceptional gratitude goes to my family for their continued support both spiritual and financial support. Thanks to my colleagues at work and my classmates for their support throughout my master’s program. My special appreciation goes to administrative officers in Embu Level Five, Comprehensive Care Clinic in charge and peer support workers for their unwavering support during collection of my research data.

Thank you all for your support.

FUNDING

None

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared, authors declare no special interest.

1. UNAIDS (2018) The global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Retrieved August 2018.

2. Kimberly G, Fujita M, Poudel KC, Wi T, Abeyewickreme I, et al. (2015) HIV service delivery models towards ‘Zero AIDS related deaths’: A collaborative case study of 6 Asia and Pacific countries. BMC Health Serv Res 15: 176.

3. Johnson K (2013) Integration of HIV and family planning health services in sub-Saharan Africa.

4. Mutemwa R, Colombini M, Mayhew SH, Kivunaga J, Ndwiga C (2016) Perception and experiences of integrated service delivery among women living with HIV attending reproductive health services in Kenya: A mixed methods study. AIDS Behav 20: 2130-2140.

5. Bergh A, Hendricks SJH, Mathibe MD (2015) Clinician perceptions and patient experiences of ART treatment and primary health care integration in ART clinics. Curationis 38: 1489.

6. Sima BT, Belachew T, Abebe F (2017) Knowledge, attitude and perceived stigma towards tuberculosis among pastoralists; do they differ from sedentary communities? A comparative cross-sectional study. PLoS One 12: e0181032.

7. Pathmanathan I, Pasipamire M, Pals S, Dokubo EK, Preko P, et al. (2017) High uptake of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive TB patients receiving co-located services in Swaziland. PLoS One 13: e0196831.

8. Wung AB, Peter NF, Atashili J (2016) Clients satisfaction with HIV treatment services in Bamenda, Cameroon a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 16: 280.

9. Kikuvi J, Church K, Wringe A, Fakudze P, Simelane D, et al. (2014) Are integrated HIV services less stigmatizing than stand-alone models of care? A comparative case study from Swaziland. J Int AIDS Soc 16: 17981.

10. Kioko J, Odeny TA, Penner J, Lewis-Kulzer J, Leslie HH, et al. (2015) Integration of HIV care with primary health care services: Effect on patient satisfaction and stigma in rural Kenya. AIDS Res Treat 2013: 485715.

11. National AIDS Control Council, NACC (2016) Kenya HIV county profiles.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Clinical Trials and Research (ISSN:2637-7373)

- Ophthalmology Clinics and Research (ISSN:2638-115X)

- Journal of Renal Transplantation Science (ISSN:2640-0847)

- Oncology Clinics and Research (ISSN: 2643-055X)

- International Journal of Anaesthesia and Research (ISSN:2641-399X)

- Journal of Forensic Research and Criminal Investigation (ISSN: 2640-0846)

- International Journal of Clinical Case Studies and Reports (ISSN:2641-5771)