2969

Views & Citations1969

Likes & Shares

Objective: To assess the existing evidence

regarding opioid use among rural dwellers.

Methods: A

detailed electronic search strategy was developed using the following

databases: CINAHL Complete, Health Source, Nursing/Academic Edition, MEDLINE

with Full Text, Psych ARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection,

Psych INFO and Social Sciences Full Text. Each study included rural subjects or

areas. Data were

extracted from 22 articles found through a systematic search encompassing 2013

– early 2018.

Results: In most of the studies (64%), the

reported findings included both rural and urban settings. Definition of the

term rural varied considerably among the different articles based on the

criteria. There is an overall increase in opioid use across the nation, but a

new research focus is the prominence of opioid use in rural communities.

Conclusion: This systematic search indicates a

need for further research in the prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and

addiction. Most of the reviewed

articles were descriptive in nature, limiting the evidence regarding the

interventions used to address the opioid crisis. There was no evidence

regarding the prescribing factors pertaining to nurse practitioners, certified

midwives and physician assistants that affect the accessibility to treatment

options in rural areas. The policy implications are to support the qualified

health care providers in rural areas to obtain waivers to provide Medication

Assisted Treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder. Moreover, it is imperative to

develop and implement policies to address the barriers to opioid addiction

treatment services provision and access in rural areas.

Keywords: Opioid use, Disuse, Misuse, Medication assisted treatment, Rural

INTRODUCTION

Effectively managing pain in patients has become an integral part of

healthcare today; it is also cause for concern with regard to the misuse of

prescribed medications and opioid abuse. Although the number of opiate prescriptions

decreased from 282 million to 236 million, national data illustrates 11.5

million persons aged 12 and over misused prescription pain relievers in 2016

[1,2]. These startling statistics have caused a prioritization shift among

national organizations and many healthcare providers when it comes to assessing

community needs. In a position statement by the American Nurses Association

addressing pain management and the opioid epidemic, nurses have an ethical

responsibility to relieve pain and the suffering it causes as well as serve as societal leaders in the development of

multimodal/interdisciplinary approaches to safely manage this crippling disease

[3]. Several factors, including a shortage of primary care providers and pain

specialists in rural areas, coalesce in rural communities to form an

environment that is conductive to an opioid crisis. Innovative, creative

collaboration between communities, national leaders and healthcare providers is

needed to provide an antidote for the many rural dwellers experiencing

adversity in opioid medication use.

Opioid

use in rural areas has unfolded into a story that highlights an increase in the

availability of prescription opioid medications as well as a brewing epidemic.

In some instances, opioid use presents as a greater challenge in rural than

urban communities. Although rural dwellers possess many positive traits such as

resilience, these areas are often inhabited with a smaller population and

equipped with limited health and social resources compared to urban communities.

Coupled with individual socioeconomic vulnerabilities (limited

education, poor health status, low income), the perfect storm is created and serves as a catalyst for an opioid

crisis [4]. While national data shows an overall increase in opioid use,

rural areas are noted to have higher prevalence of opioid and naloxone use as

well as opioid related deaths [5]. Until recently, existing bodies of

literature have largely focused on opioid use in urban areas and have often

used rural areas for comparative purposes. The aim of this review is to assess

the current evidence concerning opioid use among rural dwellers.

METHODOLOGY

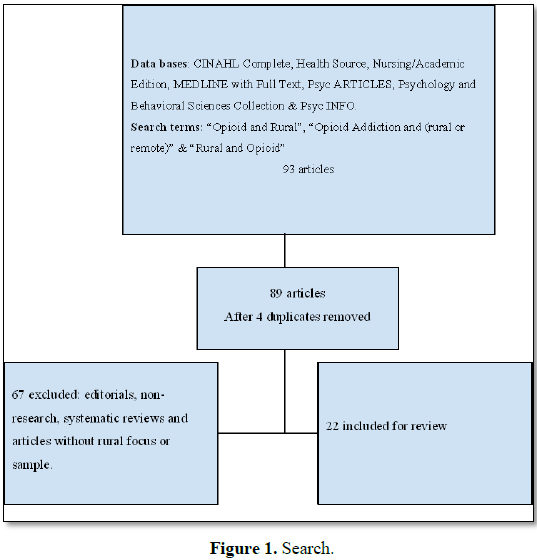

This systematic review is reported using the

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

standards [6]. This method of reporting consists of an internationally

recognized 27-item checklist developed to ensure quality in systematic

reviewing. To identify literature for review, a detailed online search strategy

was developed using the following databases: CINAHL Complete, Health Source,

Nursing/Academic Edition, MEDLINE with Full Text, Psych ARTICLES, Psychology

and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Psych INFO and Social Sciences Full Text.

These databases were searched with the intention of reviewing literature

pertaining to opioid drugs and rural areas. Search terms “opioid AND rural” as

well as “opioid addiction AND (rural or remote)” did not provide adequate

search results. A different strategy including the terms: “rural n5 opioid”

(rural within 5 words of opioid) was applied. This new strategy presented

adequate results and was thus utilized in this review. The search was limited

to English language and peer reviewed domestic or international articles

published between the years of 2013-2018. This search produced 93 possible

results. Four articles were duplicates and removed leaving 89 for further

consideration.

A careful

review of the abstract and methodology of each article resulted in deletion of

67 articles that were editorials, non-research, systematic reviews or did not

pertain to rural populations. 22 articles were appropriate for final review (Figure 1).

RESULTS

The literature in this systematic review was

primarily descriptive or epidemiological in design (Table 1) [7-28] Table 2

provides information on sampling methodology and sample size on all of the

studies. Sample sizes range from 28-75,964 with the studies with high sample

sizes coming from secondary analysis of national data sets [9,28]. Slightly

less than half (10) used secondary data to conduct research [10,12-14,18-20,26-28].

Several articles used federal data set to identify physician waivers for

prescribing opioid treatments [13,14,20]. Three studies used the National

Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [19,27,28]. Finally, authors of two

papers used the same data source (NSDUH) for the same time period (2011-2012)

to release two different studies with different populations [19,27].

Rural

Although rural was used in the search terms, 64% of the articles sampled rural and urban

populations. The remaining 36% of the articles discussed rural only (Table 3). Another factor that varied greatly between

studies was the definition of the term rural (Table 4). Some articles defined rural based on codes such as zip

codes, Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC) or Urban Influence Codes (UIC). Other

articles used abstract quantifiers such as perceived social and health status

of underserved areas and simply the name of a region, such as Appalachia.

Additionally, several articles identified rural areas as those considered

underserved in access to health and social services or provided no definition

of rural.

Place

Two studies were conducted outside of the

United States, in Australia; New South Wales and Vietnam [7,9]. All remaining

articles were conducted in the United States. A few locations are mentioned

more than others. For example, two groups conducted their studies in Cortland

County, NY [20,23]. Three groups of authors conducted their studies in Kentucky

[10,21,22]. Both upstate NY and the eastern region of KY are part of the

Appalachia Mountain Range and presented as rural in the research.

Similarities and differences in findings

Findings indicate that there is little

research regarding interventions for opioid drug abuse in either rural or

non-rural locations. The intervention that received the most attention in the

review of literature was the number and distribution of Medication Assisted

Treatment (MAT) for opioid use and misuse The major intervention reported in

the literature was regarding efforts to increase the number of providers who

can prescribe MAT for opioid use disorder in both rural and more metropolitan

areas [8,13,14,20].

The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act

(CARA) originally authorized physicians to prescribe buprenorphine in the

treatment of opioid use disorders and have been expended to include prescribers

such as nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. This law was enacted in

2016 for the purpose of opioid abuse prevention and treatment. Following the

enactment of CARA, there were moderate increases in the number of providers

with waivers. At the conclusion of 2017, 33,876 physicians, 3,534 Nurse

practitioners and 912 Physician assistants had received waivers to prescribe

Buprenorphine [29]. More research is warranted in this area so interventions

can be developed and implemented to increase the knowledge of prescribers and

to make the use of MAT readily available. There was a dearth of literature

focused on prevention of opioid abuse.

Another area deserving further research is

the use of Fentanyl on the streets. Fentanyl is an opioid used to treat pain

and can be used as an anesthetic drug when combined with other substances. In

the literature reviewed for this paper, there was no mention of Fentanyl.

However, prior to completion of this manuscript, a National Public Radio story

was released that focused on the use of Fentanyl on the streets and the high

overdose rates associated with its use [30]. The media indicates that Fentanyl

is being used illegally on the streets along with other opioids such as Heroin.

Antidotal evidence indicates overdose deaths are higher with the use of

Fentanyl, which is often combined with Heroin as an additive. This is referred to

as the third wave in the opioid crisis stating that prescription drug misuse

was the first wave, heroin the second and Fentanyl is the third. The story did

not indicate if there is a rural/urban difference in Fentanyl misuse. The

incidence of misuse of Fentanyl is occurring most frequently in the eastern

part of the United States [30]. The above news release can be traced back to a

National Vital Statistics report from the U. S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for

Health Statistics report in 2019 [31]. This warrants further study and research

into the effects of this specific drug in relation to the opioid crisis.

Opioid use is increasing as supported by more

than one article. For example researchers illustrated that opioid

poisoning almost doubled between 2001-2011 in the state of California [12]. An

international report examined four rural sites in an area of Australia

and found an increase in individuals on opioid maintenance treatment over a

period of four years [9]. The increase was more than 30% for three of the sites

over the four years and this study referred to opioid misuse as a global

crisis. No single study refuted the existence of an opioid crisis.

The questions of whether opioid use has

increased more in rural than urban environments is still under debate. Research

results indicated that Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) increased

2-2.5 times per 10,000 births in rural and Appalachian counties compared to

urban and non-Appalachian Kentucky counties between 2008-2014 [10]. In 2013,

Kentucky NAS was more than double the national rate. Moreover, opioid

facilities were further from rural and Appalachian areas compared to

micropolitan/metropolitan and non-Appalachian areas (p<0.001) [10]. Similarly,

the conclusion of one national study was that rural adolescents had 35% greater

odds than their urban counterparts in Prescription Opioid Misuse (POM) [27]. The

opioid misuse was reported as 6.8% rural, 6% small urban and 5.3% for urban adolescents.

Although there is a clear trend of less POM in areas of increasing population;

reporting the level of residency in three levels may have slightly inflated the

odds of rural misuse over the more traditional two level comparisons. A spread

in prescription opioid poisoning hospital discharges, from rural and

suburban/exurban to urban areas, was found in a California state wide study [12]. One study

utilized primary care patient record forms to examine the difference

between rural residency and non-rural residency in obtaining opioid

prescription for Non-Malignant Chronic Pain (NMCP) and found that “rural

residents had higher odds of having an opioid prescription than similar

non-rural adults. Rural residency was the strongest predictor for having an

opioid prescription and a diagnosis for NMCP” (p.5) [18].

Although there were some studies that

reported an increase of opioid use in rural areas over urban, there were a few

studies that did not support this hypothesis [11,19,28]. One national study reported

that prescription opioid misuse was more common in urban than rural areas;

while another found no difference between the two [19,28]. Rigg and Monnat [19]

speculated that previous studies finding more opioid misuse in rural areas may

have had too small or a specific geographical limit in sample.

In addition to demographics, several surveys

used self-report, paper and pencil instruments to measure attributes for a wide

array of variables, such as alcohol disorders, chronic diseases, depression,

drug abuse status, health status, mental status, opioid misuse, pain, quality

of life, psychological distress, post-traumatic stress disorder and sleep

disorders.

Two articles used pain scales [7,25]. One study utilized

a visual analogue scale for pain assessment, with respiratory rate and blood

pressure to conclude that ketamine is equitable to morphine in its analgesic

effect in emergency situations where evacuation is particularly difficult [7].

One study had three pain measures, appropriate to their population of rural

patients with chronic pain [25]. The first measure was a structured pain

interview. The Wisconsin Brief Pain Inventory, measure of pain intensity and

interference and the pain catastrophizing scale both were reported as having

good psychometrics [25]. Most authors used more than one instrument for data

collection.

Social determinants of health

Increase in opioid use was sometimes

associated with other health disorders and socio-economic factors. Patients

receiving opioid medications in rural settings have poorer overall health,

higher pain levels, lower levels of education and higher rates of unemployment

than their urban counterparts [11,15]. Similarly, another study showed

that rural individuals who reported good health were less likely to use opioid

prescriptions for non-medical reasons than those who reported poor health [28].

Studies showed that lower income and manual labor were associated with an

increase in prescription opioid poisoning or prescription opioid misuse [12,19].

In addition to the general health

deteriorations that are associated with opioid use or misuse, one study found

an association between the hospital discharge diagnostic code, prescription

opioid misuse and major psychological distress [20]. Another showed an association between Anti-Social Personality

Disorder (ASPD) and hydrocodone, crack or powder cocaine, marijuana, alcohol

and heroin use [21]. One study reported significant association between

HCV (Hepatitis C Virus) and a network of non-medical prescription opioid users [23].

Similarly, another found a strong association between prescription opioid

analgesics and positive HCV [24]. In addition, arthritis was associated with

opioid use in two different studies [12,15].

The issue of ethnicity/race and opioid use is

conflicting and may be shaped by media that emphasis the newness of rural opioid reports [16,18,19,28]. In

exploring opioid prescription risk factors in a sample with Non-Malignant

Chronic Pain (NMCP), race was reported as a factor; “being non-Caucasian

was a strong predictor of having an opioid prescription and a diagnosis for

NMCP” (p 5) [18]. In a study that was not limited to chronic pain patients, black

and non-Hispanic residents were less likely than white urban residents to use

prescription opioids for non-medical reasons [28]. Yet another concluded that

white urban residents were significantly more likely to misuse prescription

opioids [19]. A content analysis of a random selection of 100 popular media

articles on the opioid crises reported “…a consistent contrast between

criminalized urban black and Latino heroin injectors with sympathetic

portrayals of suburban white prescription opioid users (p. 664) [16]. Media

reporting of drug use in urbanized areas was found to be reported in stories

that emphasized violence and arrests [16]. In contrast stories regarding rural

drug use emphasized the unexpectedness of the problem and highlighted personal

stories that humanized the individual [16].

In addition to race, social network was one

of the considered variables in rural opioid use. One study reported that

rural residents who have used drugs associated with network characteristics,

such as having trust above the average in one’s network, had lower odds of

being diagnosed with ASPD [21]. Those non-medical prescription opioid users with HCV

tended to cluster together, which suggests the need for the development of a

network-based intervention to prevent the spread of HCV [23]. Still

another suggested the utilization of school nurses, technology and

social media in opioid management [17].

Opioid use was associated with individuals

with low income and manual labor jobs in a at least two studies [12,20]. Results of

one study showed that lower income and manual labor were associated with

an increase in the hospital discharge diagnosis of prescription opioid

poisoning [12]. Another, also found those working in manual labor had

higher rates of prescription opioid misuse [20].

An intersection between other demographic

variables and the opioid use or misuse emerged in this review of the literature. A study by

Rigg and Monnat [19] found misuse of prescription opioids were

associated with other factors such as age (young), marital status (unmarried),

difficult financial status and less religiosity. Unsurprisingly, these findings

were similar to the findings in another national analysis of the NSDUH data set

[28]. These findings indicate opioid use and misuse are influenced by different

demographic variables and no one set of variables can explain an opioid

problem.

Physician waivers for buprenorphine

prescriptions were discussed in several articles [8,13,14,20,24]. A possible

rationale for the lack of research in the published literature on waiver

practices beyond that of physicians is the newness of the extension of CARA [29].

Two studies

that went beyond the numbers of physicians with prescription waivers, found

that there were barriers for obtaining the waiver of buprenorphine maintenance

treatment [8,24]. These barriers included time, finances, clients’ needs and

worries about violating patient confidentiality. After examining the Drug

Enforcement Administration (DEA) list questionnaire, a different study found

that family physicians were five times more likely to prescribe buprenorphine

than other physicians, a statistically significant finding [24]. Only 28% of

trained physicians reported prescribing buprenorphine. Abstaining from

prescribing buprenorphine was associated with lack of institutional support

[24].

A study in Washington state including

American Indian and non-American Indian, rural and urban sites offering Opioid

Assisted Treatment (OAT) found that “the number of clinics offering OAT in

rural versus urban regions was significantly lower, indicating that

difficulties may remain for rural residents in terms of accessing most OAT

services offered in these facilities” (p. 105) [14]. One study found that the

number of physicians with waivers increased in shortage counties between

2002-2011; however, opioid treatment program access remained the lowest in

counties with populations less than 2,500 individuals [13].

Around 90% of physicians with waivers are located in urban areas and only

about 1.3% practiced in the most rural areas [20]. These authors concluded

rural residency was associated with lack of access to buprenorphine

prescriptions [20].

LITERATURE

LIMITATIONS

Authors routinely discussed possible

limitations of their research. One limitation pertinent to research on

sensitive topics included recognition that participants may be reluctant to

disclose opioid use or misuse due to stigma and possible legal ramifications.

Lack of anonymity is often considered inherent in rural research (particularly

with small sample sizes) and clinical practice in rural areas. Although

appropriate to the design, at least one article reported data collected from

twenty years ago [15].

CONCLUSION

Although there is no doubt about the spread of

negative effects and side-effects of opioid use and misuse, past perceptions of

drug use as primarily an urban problem, were not supported in this review. The

research was inconclusive on the question of where opioid abuse is worse, in

rural or urban environments. How rural was operationalized differed from one

study to another, adding to the lack of clarity regarding exactly how severe an

opioid problem exists in rural areas. In addition to the geographical factors

that may be associated with opioid use and misuse; physical, psychological,

social, financial, occupational and religious factors were reported.

Although buprenorphine prescribing was

studied in a sub-set of the articles, more interventional studies about opioid

management are needed. More than half of the reviewed articles were descriptive

and based on secondary data analysis. Interventional studies for opioid misuse

prevention and management is suggested. These types of interventional studies

are needed to provide evidence on how to best decrease the opioid crisis. The

literature reviewed failed to produce data on implementation of solutions,

beyond measuring the number of and location of physicians with MAT prescribing

waivers. As interventions are developed and tested, healthcare providers,

public health officials and policy makers need to expect that transcribing

potential urban solutions into rural settings will be difficult given the many

differences in lifestyle and circumstances among rural and urban residents,

Further study is needed to develop rural-specific solutions.

The literature reviewed did not provide

evidence of prescribing factors of Nurse Practitioners, Certified Nurse

Midwives and Physician Assistants and how this may influence the accessibility

to drug treatment in rural areas. As more data is collected on the prescribing

practices of waivered healthcare providers beyond physicians, it will be

critical to conduct research to see if these types of prescribers will help

meet the needs for MAT in rural areas. Policy makers should ensure that all

qualified healthcare providers, not only physicians, are able to provide MAT in

order to improve treatment access to people in rural areas. Reports continue to

come forth regarding the work being done to overcome barriers to providing MAT,

particularly buprenorphine, in rural areas [29].

Strengths of this systematic review include

the wide search for peer-reviewed literature on the chosen topic. This review

establishes baseline data with which to compare future research. The review

also establishes the current state of knowledge and identifies gaps in the

literature to date. The topic of opioid use and misuse is crucially important

and has been identified as a public health crisis. Exploring the trend of

opioid addiction in rural areas along with approaches for prevention and

treatment progress are needed to meet the goals of public health.

1. Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J, Hedden SL, Lipari RN, Park-Lee E (2017) Key

substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from

the 2016 national survey on drug use and health (HHS Publication No. SMA

17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health

Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018) U. S. Prescribing Rate

Maps.

3. American Nurses Association (2018) Practice & Policy. American

Nurses Association Website.

4. Noonan R (2018) Rural America in crisis: The changing opioid overdose

epidemic. CDC Website.

5. National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Humand Services (2016)

Families in crisis: The human service implications of rural opiod misuse.

Rockville: Health Resources & Services Administration.

6. Moher D, Liberati A, Tezlaff J, Altman D (2009) Preferred reporting

items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:

332.

7. Tran KP, Nguyen Q, Truong XN, Le V, Le VP, et al. (2014) A comparison of

ketamine and morphine analgesia in pre-hospital trauma care: A cluster

randomized clinical trial in rural Quang Tri Province, Vietnam. Prehospital

Emergency Care 18: 257-264.

8. Andrilla CHA, Coulthard C, Larson EH (2017) Barriers rural physicians

face prescribing buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med 15:

359-362.

9. Berends L, Larner A, Lubman DI (2015) Delivering opioid maintenance

treatment in rural and remote settings. Austr J Rural Health 23: 201-206.

10. Brown JD, Goodin AJ, Talbert JC (2018) Rural and Appalachian disparities

in neonatal abstinence syndrome incidence and access to opioid abuse treatment.

J Rural Health 34: 6-13.

11. Cochran GT, Engel RJ, Hruschak VJ, Tarter RE (2017) Prescription opioid

misuse among rural community pharmacy patients: Pilot study for screening and

implications for future practice and research. J Pharmacy Pract 30: 498-505.

12. Cerdá M, Gaidus A, Keyes KM, Ponicki W, Martins S, et al. (2017)

Prescription opioid poisoning across urban and rural areas: Identifying

vulnerable groups and geographic areas. Addiction 112: 103-112.

13. Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, Mark Sorbero, Rachel M, et al. (2015)

Growth in buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to

opioid agonist treatment, 2002-11. Health Affairs 34: 1028-1034.

14. Hirchak KA, Murphy SM (2017) Assessing differences in the availability

of opioid addiction therapy options: Rural versus urban and American Indian reservation

versus non-reservation. J Rural Health 33: 102-109.

15. Karp JF, Lee CW, McGovern J, Stoehr G, Chang CCH, et al. (2013) Clinical

and demographic covariates of chronic opioid and non-opioid analgesic use in

rural-dwelling older adults: The MoVIES project. Int Psychogeriatr 25:

1801-1810.

16. Netherland J, Hansen HV (2016) The war on drugs that wasn’t: Wasted

whiteness, “dirty doctors” and race in media coverage of prescription opioid

misuse. Cult Med Psychiatry 40: 664-686.

17. Pattison-Sharp E, Estrada RD, Elio A, Prendergast M, Carpenter DM (2017)

School nurse experiences with prescription opioids in urban and rural schools:

A cross-sectional survey. J Addict Dis 36: 236-242.

18. Prunuske JP, St Hill CA, Hager KD, Lemieux AM, Swanoski MT, et al.

(2014) Opioid prescribing patterns for non-malignant chronic pain for rural

versus non-rural US adults: A population-based study using 2010 NAMCS data. BMC

Health Serv Res 14: 563.

19. Rigg KK, Monnat SM (2015) Urban vs. rural differences in prescription

opioid misuse among adults in the United States: Informing region specific drug

policies and interventions. Int J Drug Policy 26: 484-491.

20. Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Catlin M, Larson EH, Andrilla CHA (2015)

Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid

use disorder. Ann Fam Med 13: 23-26.

21. Smith RV, Young AM, Mullins UL, Havens JR (2017) Individual and network

correlates of anti-social personality disorder among rural nonmedical

prescription opioid users. J Rural Health 33: 198-207.

22. Young AM, Jonas AB, Havens JR (2013) Social networks and HCV viremia in

anti-HCV-positive rural drug users. Epidemiol Infect 141: 402-411.

23. Zibbell JE, Hart-Malloy R, Barry J, Fan L, Flanigan C (2014) Risk

factors for HCV infection among young adults in rural New York who inject

prescription opioid analgesics. Am J Public Health 104: 2226-2232.

24. Hutchinson E, Catlin M, Andrilla CHA, Baldwin LM, Rosenblatt RA (2014)

Barriers to primary care physicians prescribing buprenorphine. Ann Fam Med 12:

128-133.

25. Kapoor S, Thorn BE (2014) Healthcare use and prescription of opioids in

rural residents with pain. Rural Remote Health 14: 1-12.

26. Mosher H, Zhou Y, Thurman AL, Sarrazin MV, Ohl ME (2017) Trends in

hospitalization for opioid overdose among rural compared to urban residents of

the United States, 2007-2014. J Hosp Med 12: 925-929.

27. Monnat SM, Rigg KK (2016) Examining rural/urban differences in

prescription opioid misuse among US adolescents. J Rural Health 32: 204-218.

28. Wang KH, Becker WC, Fiellin DA (2013) Prevalence and correlates for

non-medical use of prescription opioids among urban and rural residents. Drug

Alcohol Dependence 127: 156-162.

29. Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, Larson EH (2019) Geographic

distribution of providers with a DEA waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the

treatment of opioid use disorder: A 5 year update. J Rural Health 35: 108-112.

30. Bebinger M (2019) Fentanyl-linked deaths: The U.S. opioid epidemic’s

third wave begins.

31. Spencer MR, Warner M, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Hedegaard H (2019) Drug

overdose deaths involving fentanyl, 2011-2016. Natl Vital Statistics Rep 68:

1-19.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Ageing and Restorative Medicine (ISSN:2637-7403)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Journal of Cancer Science and Treatment (ISSN:2641-7472)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- International Journal of Medical and Clinical Imaging (ISSN:2573-1084)

- Journal of Allergy Research (ISSN:2642-326X)