1070

Views & Citations70

Likes & Shares

This contribution conducts a mini-review of the topic

Horizontal Loyalty based on the paper written by Almeida and Moreno (2018).

The traditional

analysis of loyalty centred on a single destination and with a one-dimensional

perspective has recently been questioned. This study analyses horizontal

loyalty, and explains the factors that determine this behavior. This paper also

identifies the differences between the variables that explain horizontal

loyalty and the loyalty to a single destination. This study is the first

empirical application of this focus to a tourist destination. The results help

to understand the necessary change of focus in the study of loyalty in the

tourist context, as well as in the design of strategies, where the emphasis

should be placed on tourists. This way, destinations will be able to improve

their competitiveness.

Keywords: Horizontal Loyalty, Coopetition, Competitiveness,

Segmenting Image Motivations.

SIGNIFICANCE/IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORY AND PRACTICE

Traditionally,

research into loyalty in a tourist destination context has focused its

attention on how a destination relates to tourists to try to establish lasting

and beneficial relationships with them. However, less attention has been paid

to the study from the perspective of tourists and how these relate to

destinations (Araña et al., 2016). In order to allow destinations to be able to

improve their marketing strategies and tourist loyalty, a change of focus is

absolutely necessary (Font & Villarino, 2015; Nordbø, Engilbertsson &

Vale, 2014). “Service-dominant logic”, as articulated by Lusch & Vargo

(2006), claims for a customer-centered focus, where the context of creating

value takes ground in networks of networks (destinations and tourists in this

case). Focusing on tourists and how they establish their loyalty relationships

with different destinations will help to understand how destinations should

relate to both tourists and competitors, and it may be beneficial to foster

coopetition between tourist destinations to improve competitiveness of the

same.

Increasing

competition among tourist destinations is a significant trend (Mariani &

Baggio, 2012). This is accentuated by a larger number of holidays, albeit

shorter ones, per individual, together with the unstoppable growth of the

number of destinations in the market and the development of their offer (UNWTO,

2013), which make this change in focus even more necessary in the analysis of

tourist loyalty. While some tourists may be loyal to a single destination,

there are a large number that share out holidays between different

destinations, which may cooperate and/or compete with each other. In the

current tourism scenario, destinations are forced to increase their

competitiveness, and literature shows that collaboration and cooperation

between tourist destinations (Fyall, Garrod & Wang, 2012; David et al.,

2018), as well as the development of loyalty (Weaver & Lawton, 2011) are

relevant strategies for destinations in achieving competitive advantages in the

long term. Therefore, it is necessary to further analyse this phenomenon.

ORIGINALITY AND INNOVATION

Loyalty

is a construct that has been tackled in literature in a very homogeneous way

and all the different ways in which tourists can show their loyalty have not

been contemplated. According to McKercher, Denizci-Guillet & Ng (2012),

most studies on loyalty in the tourism industry focus on a single unit of

analysis (e.g. a single destination), and apply similar indicators, which shows

a lack of conceptual and methodological innovation. Specifically, according to

these authors, from the consumer perspective, one can speak of the existence of

horizontal loyalty – HL (Almeida & Moreno, 2017) where tourists can be

loyal to more than one supplier occupying the same level within the tourism

system. Thus, tourists can show their loyalty to several destinations at the

same time.

The

study of HL, which is hardly explored in tourism literature, requires an

alternative methodological approach and suggests a better knowledge of the

tourist and an answer to the following question: What factors really explain

the differences between HL and single-destination loyalty (DL)? In literature,

serious efforts have been made to investigate the factors that influence

customer loyalty (Han, Hyun & Kim, 2014), but there are no studies that

analyse the factors that determine whether a tourist is loyal to multiple

destinations. Thus, the objective of this research is to segment tourists

according to the way in which they manifest their loyalty to tourist

destinations and to analyse whether or not the factors that determine HL are

the same as those that determine DL.

METHODOLOGY

Europe

remains the world's largest outbound tourism region, generating more than half

of global international arrivals per year (UNWTO, 2016). For this reason, the

target population of this study was European tourists, aged 16 and over, from

17 of the main outbound European countries in terms of tourists: Austria,

Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Poland,

Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

The

work was done through Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI), to a

representative sample of the 16 mentioned countries, from a database of

panelists in each country. A random selection was made based on the variables

of stratification of geographical area and province, on the one hand, and, on

the other, of gender and age, in order to guarantee the representativeness of

the sample with the population of each country. Once the questionnaire was

translated and pre-tested in the language of the potential tourists, and the

relevant corrections were made in those questions that raised difficulties of

comprehension, the fieldwork was carried out. The defined sample was of 8,500

tourists (500 in each country) and the actual sample obtained of 6,964

tourists, between 400 and 459 tourists per country. The selected sample was

sent a personalised email inviting them to participate in the study, with a

link in the mail that led them to the online survey. In order to ensure the

expected number of surveys, during the three months of fieldwork in different countries,

two reminders were held to encourage response.

After

completing the fieldwork and having applied the corresponding quality controls,

we performed a binomial Logit analysis with the latest version of the SPSS

statistical analysis programme. In this case a Logit model based on the theory

of random utility has been chosen. The use of this model guarantees robustness

in the estimated results and the fulfilment of the properties of the

conventional utility functions established by the theory of the consumer.

In

this case, the 7 islands (destinations) that compose the Canary Islands are

considered the competitive set: Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote,

Fuerteventura, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro. This destination was chosen,

as well as for convenience, as a well-known European leading destination (Gil,

2003) and because there is an interesting complementarity between the islands

that makes it ideal for the study of HL. Two groups of tourists are

differentiated, those that show DL and those that manifest HL. A tourist can be

defined as being loyal to a single destination if at least two or more visits

to the same destination are observed, without observing other visits to the

rest of destinations considered in the competitive set (a single island of the

Canary Islands in two occasions or more, and no other). On the other hand,

tourists are considered to be HL tourists when they have visited at least two

different destinations in the group (at least two islands among the seven

Canary Islands).

DATA AND

FINDINGS

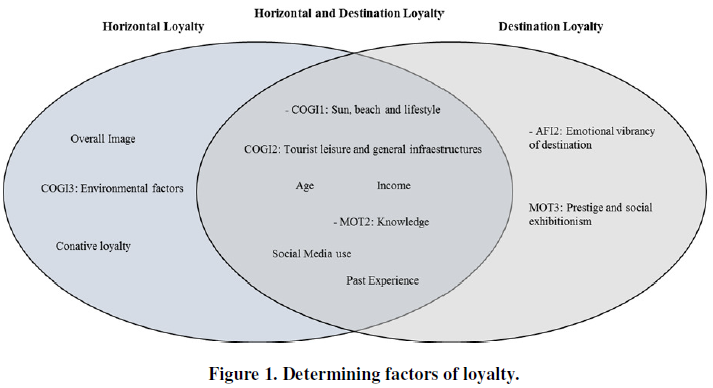

A review of literature helped to

conceptualise the subject of study: the loyalty to the destination and its

fundamental dimensions, different groups of tourists were identified according

to the type of loyalty shown: loyalty to a destination and horizontal loyalty

to multiple destinations. Subsequently, the differences in their explanatory

variables were analysed with a methodological design based on a questionnaire

made to potential tourists from 17 countries, with a large sample size (6,964

tourists) that allowed consistent conclusions to be drawn (Figure 1).

Regarding the theoretical

implications, the present study supposes the first empirical application of the

factors that determine HL, and its differences with DL, focused on tourist

destinations, where the concept of loyalty has its peculiarities (Alegre &

Juaneda, 2006). Thus, the need for a change of focus in the study of loyalty in

the context of tourist destinations is highlighted, where future work could use

the methodology and conclusions that are developed in the present research.

Traditionally, destinations and their marketing strategies have been analysed

without taking into account other tourist destinations, or the relationship of

tourists with all of them. This study proposes a change of vision in the design

of such strategies, where the emphasis is placed on the community of tourists

and how these relate to many destinations.

On the other hand, the practical

implications are obvious, since the understanding of the differences raised in

the loyalty of the tourist implies different marketing strategies for each

group, allowing the destinations to enhance their competitiveness. Thus,

destination organisations and managers of companies operating in the sector

could maximise their available resources for tourism promotion and could also

establish possible joint marketing strategies.

Specifically, the fact that the

higher the age and the level of income of the tourist influences both the HL

and the DL, means that the destinations must design loyalty programmes

especially directed to these segments, being able to work with partners where

this profile (higher age and income level) is the most common (e.g. airline

loyalty programmes). As for the negative effect of the sun and beach image on

both types of loyalty, this denotes the need for innovation by these

destinations, even with the intention to “get out of the category” of sun and

beach through innovation and differentiation if they want to keep tourists loyal.

In this line, the identification of two factors in the affective image suggests

further studying a new paradigm of the sun and beach image of destinations

(affective image of authenticity, well-being and sustainability). Likewise, the

projected image of its general infrastructures and leisure, to the extent that

they are congruent with that of the markets of origin, are also a good impulse

for loyalty. In any case, social media are an ideal source for communicating

all these proposals, as they promote both DL and HL.

In the case of destinations that

want to promote DL, in addition to the previous aspects, the projection of an

image aimed at those tourists motivated by a fashionable and prestigious

destination, which allows social exhibitionism, would seem to be an appropriate

strategy, moving away from a cheerful and stimulating destination image, as an

image shared with other places. On the other hand, to promote HL, competing

destinations can carry out joint promotional actions that help them in the conversion

of the intention to visit, working on a shared global image based on common

aspects of their environmental situation. In addition, as a means of avoiding

the tourist’s search for something new and lack of loyalty, destinations can

continually renew their attractions, in addition to being able to offer joint

proposals and itinerant events between the competing group.

Finally, some lines of future

research are suggested: a) in the first place and since this study has focused

only on a geographical area and a competitive set, the set of considered

destinations can be expanded. For example, in the once-in-a-lifetime

destinations, the extent to which these conclusions apply and whether they can

also be networked should be analysed; Furthermore, other additional indicators

may be considered to help explain the visits to each of the different

destinations (satisfaction, quality, familiarity, cultural differences, etc.),

and incorporate vertical and experiential loyalty dimensions; Analyse if the

order in which the different destinations are visited influences HL and the

determination of the number of times the group of competing destinations is

visited; To further analyse the different typologies of social media and

sources of information used by tourists to find out about their travel

destination in the determination of HL and; To evaluate loyalty from a social,

environmental and economic perspective, in its different dimensions (DL, HL)

and its implications in the brand architecture, which would allow to evaluate

the promotional proposals with better criteria.

Alegre, J. & Juaneda, C. (2006).

Destination loyalty: Consumers’ economic behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), 684-706.

Almeida-Santana, A. & Moreno-Gil, S.

(2017). New trends in information search and their influence on destination

loyalty: Digital destinations and relationship marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(2), 150-161.

Almeida-Santana, A. & Moreno-Gil, S.

(2018). Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tourism Management, 65(2018), 245-255.

Araña, J., León, C., Carballo, M. &

Moreno, S. (2016). Designing tourist information offices: The role of the human

factor. Journal of Travel Research, 55(6),

764-773.

David-Negre, T., Almedida-Santana, A.,

Hernández, J.M. & Moreno-Gil, S. (2018). Understanding European tourists’

use of e-tourism platforms. Analysis of networks. Information Technology & Tourism, 20(1-4), 131-152.

Font, X. & Villarino, J. (2015).

Sustainability marketing myopia: The lack of sustainability communication

persuasiveness. Journal of Vacation

Marketing, 21(4), 326-335.

Fyall, A., Garrod, B. & Wang, Y.

(2012). Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches

to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Journal

of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1), 10-26.

Gil, S.M. (2003). Tourism development in

the Canary Islands. Annals of Tourism

Research, 30(3), 744-747.

Han, H., Hyun, S.S. & Kim, W.

(2014). In-flight service performance and passenger loyalty: A cross-national

(China/Korea) study of travelers using low-cost carriers. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 31(5), 589-609.

Lusch, R.F. & Vargo, S.L. (2006).

Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281-288.

Mariani, M.M. & Baggio, R. (2012).

Special issue: Managing tourism in a changing world: Issues and cases. Anatolia, 23(1), 1-3.

McKercher, B., Denizci-Guillet, B. &

Ng, E. (2012). Rethinking loyalty. Annals

of Tourism Research, 39(2), 708-734.

Nordbø, I., Engilbertsson, H.O. &

Vale, L.S.R. (2014). Market myopia in the development of hiking destinations:

The case of Norwegian DMOs. Journal of

Hospitality Marketing & Management, 23(4), 380-405.

UNWTO. (2016). Tourism Highlights.

Available at: http://www2.unwto.org/en

UNWTO. (2013). Annual Report. Available at: http://www2.unwto.org/en

Weaver, D.B. & Lawton, L.J. (2011).

Visitor loyalty at a private South Carolina protected area. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3),

335-346.