Research Article

CONTRIBUTION OF LENDING INSTITUTIONS IN THE GROWTH OF INDIAN AGRICULTURE

3959

Views & Citations2959

Likes & Shares

The study examined the role of lending institutions in the development of Indian agriculture. Data for the study was obtained from secondary sources obtained from published articles, annual reports of RBI, NABARD, publications of Central Government Offices etc. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as percentages, frequencies and compound annual growth rate (CAGR). The results reveal that in the early years particularly during the pre-green revolution era, agricultural credit was dominated by non-institutional sources, mainly moneylenders who are known to extort the farmers by charging exorbitant interest rates. However, the turn of the post liberalization era witnessed a paradigm shift with the institutionalization of agricultural credit in India. This has led to a remarkable success in terms of agricultural credit provision with the institutional sources of credit performing a leading role in agricultural credit delivery to farming households. Recently, institutional credit sector has performed astonishingly by surpassing its annual targets with few exceptions from 2011-12 to 2018-19. Furthermore, the results indicate that the commercial banking sector has controlled its counterparts in agricultural credit disbursement in rural areas as pictured by both CAGR and achieved credit targets of the institutions.

Keywords: Indian agriculture, Commercial banking sector, Lending institutions, Agricultural credit.

Credit is arguably the most important input for conducting all agricultural development programmes as it enables farmers to make new investments as well adopt recent technologies that will ensure increased production and productivity of their farming enterprise(s). The importance of agricultural credit is further reinforced by the unique role of Indian agriculture in the macroeconomic framework along with its significant role in poverty alleviation (Kumar, et. al. 2010). Credit refers to certain amount of money provided for certain purpose on certain conditions with some interest, which can be repaid later. It is a means of obtaining resources at a certain period of time with an obligation to repay it, usually with some interest at subsequent period in accordance with the terms and conditions of the credit obtained. Thus, agricultural credit is money extended to farmers to stimulate the productivity of the limited farm resources. Numerous studies show that there is strong positive correlation between agricultural growth and timely availability of credit. Technological breakthrough in Indian agriculture has led to substantial increased demand for credit. Thus, in order to sustain and accelerate the technological change in agriculture, sector, the availability of adequate credit and its use in the most efficient way is extremely imperative (Acharya & Agarwal, 2016).

Lending institutions play an enormous role in the development of Indian agriculture and the economy as a whole through mobilizing savings and disbursing them into productive economic activities in the form of credit. In the early days, there was no effective institutional agency to finance agricultural activities in India and the prime source of agricultural credit was moneylenders. These moneylenders are historically known to extort agriculturists by charging exorbitantly high interest rates which threaten the livelihood of the farming households and in some cases, can drag them into vicious cycle of poverty. Agriculture development remains center to the economic and social life of much of the developing world (Kumar, et al. 2010). It is par excellence, the fundamental industry because it is the basis of the existence of human race and plays an important role in generating employment opportunities and supplementing the small, marginal and landless labourers (Baker, Barasodi & Wilson, 1953). All the three (3) basic objectives of economic development of developing nations, namely; output growth, price stability and poverty alleviation are best achieved through the growth of agriculture sector. In recognition of the agricultural credit as a catalyst for promoting agricultural growth and development, the Indian Government emphases on the institutional framework for agricultural credit. Several policy measures were initiated to improve the accessibility of farmers to institutional sources of credit by providing timely and adequate credit support to all farmers with special attention to small and marginal farmers to enable them to adopt modern technology and improved production practices. As a result, a large number of formal institutions like Co-operatives, Regional Rural Banks (RRBs), Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs), Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs), and Self-help Groups (SHGs), etc. were rolled up and involved in the provision of short, medium and long-term credit needs of the farmers. The major milestones in improving the rural credit include the acceptance and implementation of Rural Credit Survey Committee Report (1954), nationalization of major commercial banks (1969 & 1980), establishment of Rural Regional Banks (RRBs) in 1975, establishment of National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in 1982, the financial sector reforms (1991 onwards), Special Agricultural Credit Plan (1994-95), launching of Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs) in 1998-99, Doubling Agricultural Credit Plan within three years (2004), and Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme in 2008. These initiatives had a positive impact on the credit flow in agriculture sector. Despite all these initiatives, there seems to be inadequacy of credit to agriculture in India as money lenders are still believe active in the rural credit market. This is a serious concern that that is worthy of being addressed. This study is intended at examining the role played by lending institutions in the development of Indian agriculture through the provision of required credit support to the farming community.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted using secondary data which was obtained from different reputable sources which include published journal articles, annual reports Data for the study was obtained from published papers, annual reports and statistics as well as websites of NABARD, Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India etc.. The data were subjected to appropriate statistical analytical techniques such as such as estimation of percentages, compound annual growth rate (CGAR) in order to determine the credit flow and the role it played in the development of the Indian agriculture.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

Evolution of Agricultural Finance in India and Policy Milestones

According to RBI (2019), the evolution of agricultural credit policies and milestones can be broadly categorised into three distinctive phases.

Phase I: The Pre-Green Revolution Period (1951–1969): The Government of India initiated the first five-year plan in 1951 with the thrust on developing the primary sector. The National Credit Council in a meeting held in July 1968 emphasised that commercial banks should increase their involvement in the financing of priority sectors, viz., agriculture and small-scale industries, sectors deemed as ‘national priority. In 1969, when the first phase of nationalisation of banks took place, there were 6955 public sector bank branches and the average population per branch office was 64,000 (RBI, 2019). To boost rural development, the Reserve Bank of India had then prescribed 1:3 ratio for opening of branches in urban and rural/semi-urban centres.

Phase II: The Post-Green Revolution Period (1970-1990): The channel for institutional credit to agriculture during the first two decades of independence was only the cooperative sector. With the nationalisation of commercial banks in 1969, the decade of 1970s marked the entry of commercial banks into financing agricultural activities. This period witnessed the introduction of the Lead Bank Scheme and regulatory prescription of Priority Sector Lending; two landmark development policies that have not only survived till date but have also served as the fuel for channelling agricultural credit and rural development. The Regional Rural Bank Act, 1976 was enacted to provide sufficient banking and credit facility for agriculture and other rural sectors. The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) came into existence in 1982, with the enactment of NABARD Act 1981, to promote agriculture and rural development. NABARD, in 1992 introduced the Self-Help Group (SHG) model to further financial inclusion of the excluded segments. In 1989, the Reserve Bank introduced the service area approach (SAA) and Annual Credit Plan (ACP) system as tools for reaching out to the rural areas.

Phase III: The Post Liberalization Period (1991 onwards): The economic reforms of the 1990s, started with the implementation of the first Narasimham Committee Report of 1991, which emphases financial soundness and operational efficiency of the financial sector, including that of rural financial institutions. The Reserve Bank of India gradually deregulated the interest rate regime to aid improvement in the operational efficiency of banks. The first major nationwide farm loan waiver was announced in 1990 and the cost to the national exchequer was around Rs.100 billion. Pursuant to the 1995 union budget announcement, the government established the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) with NABARD. RIDF was mainly meant for funding of rural infrastructure projects which in turn were invented to deepen the credit absorption capacity in a state by giving loans to state governments and state-owned corporations. Scheduled commercial banks contribute to the corpus of the fund to the extent of their shortfall in achieving the priority sector lending target. During 1992-93, NABARD started the pilot project on SHG-Bank Linkage programme - a partnership model involving SHGs, banks and NGOs. In the initial years, the scheme progressed slowly but picked up gradually. The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) was introduced as a financial product in 1998 to provide hassle free credit to farmers. The Union Government introduced the Ground Level Credit (GLC) policy in year2003-04, with GLC targets for agriculture and allied sector in the union budget every year which banks are required to achieve during the financial year. These targets are set region-wise, agency-wise (SCBs, RRBs & Cooperative banks) and loan category wise (crop and term loan).

Another policy initiative, introduced in 2004–2005, was to double the volume of credit to agriculture over a period of three years and expand the reach of formal finance. The year 2006 saw a host of developments. Pursuant to the budget announcement for 2006-07, the Union Government introduced the interest subvention scheme (ISS) for short term crop loans to enable farmers to avail farm credit at reduced interest rates for timely repayment. The Business Correspondents (BCs) and Business Facilitators (BFs) were rolled out for the first time by the Reserve Bank of India to further the cause of financial inclusion. NABARD introduced the Joint Liability Group (JLG) model, an extension of the earlier SHG model for reaching out to tenant farmers and share-croppers with access to credit. Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS), 2008 announced by the Union Government involved waiving institutional debt for small farmers and a one-time settlement opportunity with 25 per cent rebate to other farmers. This massive write-off of agricultural loans involving Rs.525.166 billion was envisaged to provide relief to the persistent problem of farmers’ indebtedness and alleviate the financial pressure faced by the farmers. In 2009-10, the Government introduced the prompt repayment incentive (PRI) of 3 per cent under the ISS to bring down the effective rate of interest to 4 per cent to those farmers who repaid their loans on or before the due date to inculcate repayment habits. In July 2012, the Priority Sector Lending (PSL) guidelines were revised by the Reserve Bank to widen the eligible activities. Again in April 2015, the guidelines were revamped based on the recommendations of the Internal Working Group (IWG).

The salient features of the revamped PSL guidelines relating to agricultural sector include (a) the distinction between direct and indirect agricultural credit was dispensed with, (b) a sub-target of 8 per cent of ANBC or Credit Equivalent Amount of Off-balance Sheet Exposure, whichever is higher, was prescribed for small and marginal farmers, and (c) focus shifted from ‘credit in agriculture’ to ‘credit for agriculture.

Indian Agricultural Credit Structure

The Indian agricultural credit sector mainly consists of three major parts; the commercial banks, cooperatives banks and rural regional banks with reserve bank of India, the apex bank and monetary authority of the nation at the top of the hierarchy. NABARD was created to monitor and regulate the agricultural credit activities of Indian Agricultural credit sector (Figure 1).

Trend in Agricultural Credit

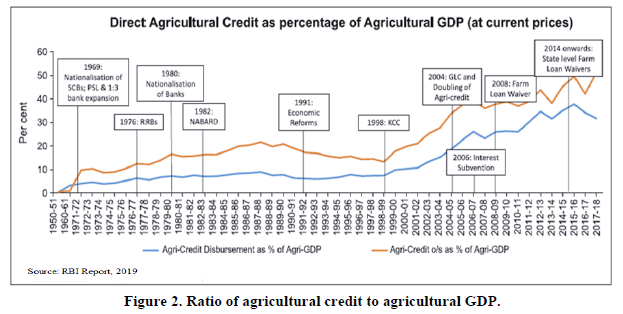

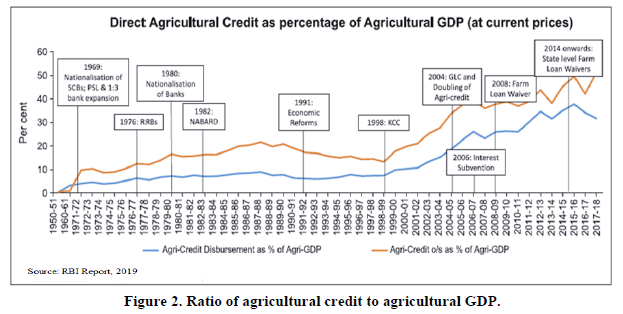

In order to properly understand the impact of the policy milestones (discussed above) on agricultural credit and its performance with respect to agricultural GDP, RBI (2019) computed the ratio of agricultural credit to agricultural GDP taking into account the agricultural credit outstanding as well as disbursement in Figure 2.

Figure 2 revealed that the ratio of Agri-Credit outstanding to Agri-GDP jumped from 0.6 per cent in 1950-51 to 9.81 per cent in 1971-72. Post 1972, the ratio showed an upward trend up to 1987- 88 increasing to 21.76 per cent. The impressive achievement of agricultural credit against agricultural GDP during 1950s-1980s is on account of nationalisation of banks and introduction of RRBs which expanded the reach of formal credit in the country. However, the reverse trend in the ratio was observed from 1990-91 onwards and it fell to 13.34 per cent in 1998-99. Post 1999 the ratio increased steeply and reached up to 39.55 per cent in 2006-07, which indicates that introduction of KCC was a big booster for agricultural credit and brought about a significant transformation in improving the reach of credit to the farming community. In later years, despite a fluctuating trend, it embalmed to 49.63 per cent in 2015-16 and 51.56 per cent in 2017-18. The chart depicts that the trend of both the agri-credit outstanding as well as disbursement as percentage of agri-GDP are largely similar except in certain periods. The reasons could be announcement of loan waivers which negatively impacted the repayment habit of the borrowers and also made the lending institutions averse to fresh lending. Despite these spectacular achievements, the dependence of agricultural households on non-institutional sources persisted over the years, though reduced to large extent.

Performance of agricultural credit

Agricultural credit began to rise from the moment attention was shifted towards the establishment of institutional credit sources and picked up the pace with the nationalization of banks. This has led to a significant increase in the access of rural farmers to institutional credit and decline in the contribution of informal agencies towards credit advancement. The share of institutional agencies in the total agricultural credit supply was only 7.0 per cent in 1951, which jumped to 66.3 per cent in 1991. The next decade witnessed a slight decline in its share and it fell to 64.3 per cent in 2002-03 (Kumar, et. al. 2010). The government has made renewed efforts to enhance agricultural credit supply and institutional sources of credit more than quadrupled in the in recent years. Approaches like nationalization of banks, establishment of RRBs, strengthening of credit institutions by NABARD etc. have proven very effective in reducing the role of informal agencies in rural credit market. Unfortunately, non-institutional agencies still continue to play a significant role in the rural credit market. Evidences illustrate that rural farmers still rely on moneylenders and other informal sources despite their exploitation in the form of high interest rates due to easy accessibility, timely and also for non-productive purposes. Kumar et al. (2007) reported that the interest rate being charged by the informal credit sources ranges from 36 per cent to 120 per cent per annum.

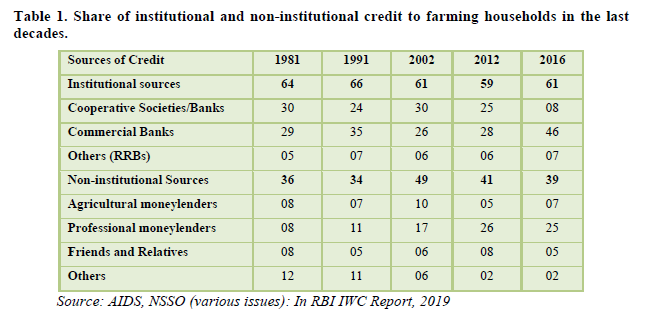

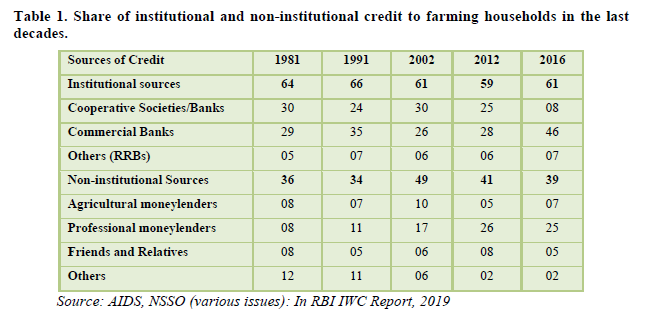

Institutional credit refers to credit obtained from the formal regulated sector of the economy and includes such sources as government, cooperative societies/banks, commercial banks including RRBs, insurance companies, etc., while the non-institutional credit is mainly obtained from unregulated section of the economy and include landlords, friends and relatives, agricultural moneylenders, professional moneylenders, traders and input suppliers among others.

The results shows that institutional credit has taken over the role of agricultural credit from its non-institutional counterpart with total contribution of 64 percent in 1981, 66 percent in 1991, 61 per cent in 2002, 59 per cent in 2012 and 61 per cent in 2016 respectively (Table 1). This is in line with recent studies including Kumar et al. (2010) who reported that the share of agricultural credit to farming households is now conquered by the institutional credit sector. The results further revealed that cooperative banks had disbursed more credit to agriculture sector in the decades of 1981 (30%) and 2002 (30%) as compared to commercial banks (29 per cent in 1981 and 26 per cent in 2002). However, the reverse is the case in the decades of 1991, 2012 and 2016 with commercial banks’ disbursement of 35 per cent in 1991, 28 per cent in 2012 and 46 per cent in 2016 as compared to cooperative banks(24% in 1991; 25% in 2012; and 8% disbursement). Non-institutional credit sector contribution over the decades were to the tune of 36 per cent in 1981, 34 per cent in 1991, 49 per cent in 2002,41 per cent in 2012 and 39 per cent in 2016 respectively with professional moneylenders and landlords playing a more consistent role of credit providers.

Commercial banks were observed to outperform both regional rural banks and cooperative banks with minimum and maximum contribution of 70.23 per cent and 75.68 per cent, respectively during 2009-2019 (Table 2) indicating its dominance in terms of agricultural credit delivery. Similarly, RRBs are found to perform the lowest based on per cent credit disbursement with a minimum value of 9.84 per cent and maximum value of 13.03 per cent, respectively over the study period due to existence of branches in certain areas and financial soundness. The findings are in harmony with Kumar et al. (2010) who reported that RRBs are contributes less to agricultural credit in per cent term when compared to their commercial counterparts.

Further, the results reveal that RRBs accomplished with the highest CAGR of 17.58 per cent while cooperative banks recorded the lowest value of 10.34 per cent CAGR in the same period. RRBs are expected to have more return to the capital invested as compared to its counterparts and cooperatives will have the lowest rate of returns if the returns to invested over the period. The combine average CAGR for all the financial institutions (banks) was found to be 14.06 per cent.

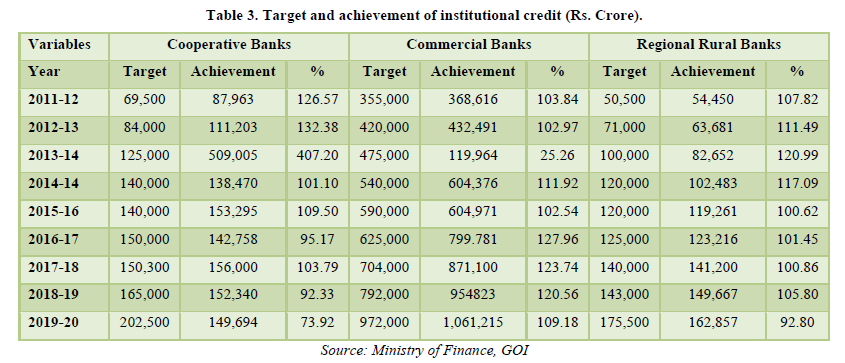

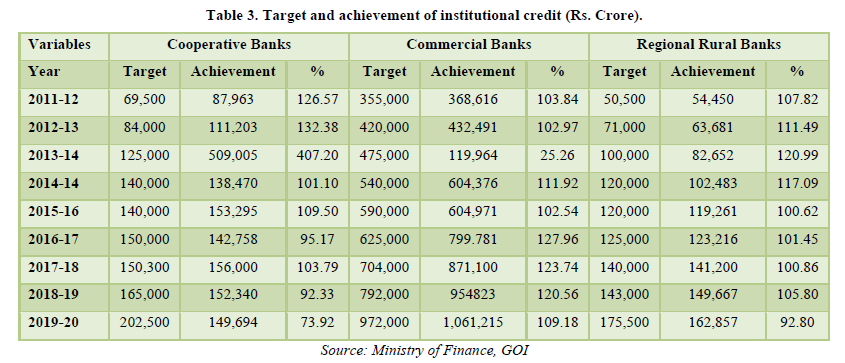

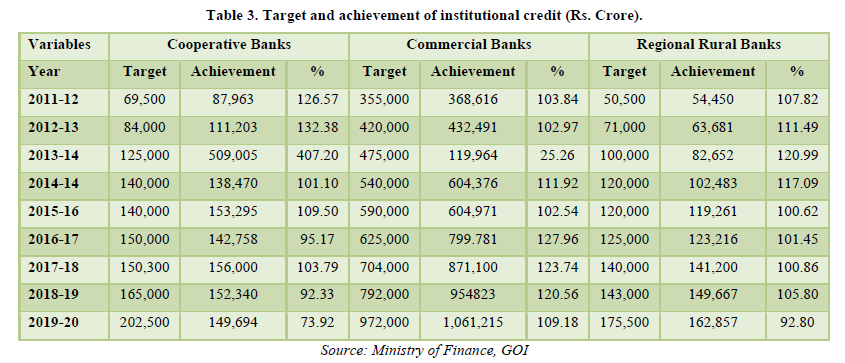

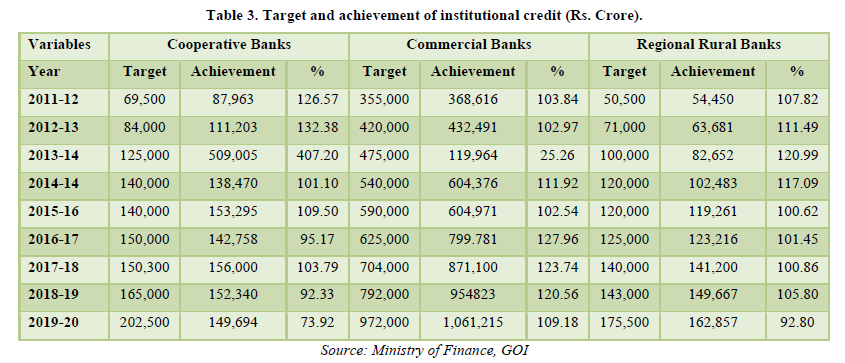

The results indicate that the institutions have surpassed their set credit targets remarkably during 2011-2020 (Table 3). Cooperative banks have achieved remarkable performance in credit delivery targets over years with except few years i.e. 2016-17 (95.17%), 2018-19 (93.33%), and 2019-20 (73.92%). Highest performance of cooperative banks was recorded in 2013-14 where the target was achieved 407.20 per cent disbursement of credit. Similarly, commercial banks have achieved their credit delivery target between during the period except in 2013-14 where it performed woefully with only 25.26 per cent credit target attainment. Outstanding performances of commercial banks were recorded in 2016-17 (127.96%), 2017-18 (123.74%) and 2018-19 (120.56%). Among all the institutions, only RRBs were found to meet their credit disbursement targets during the entire period with 2013-14 (120.99%), 2014-15 (117.09%) and 2012-13 (111.49%) being their most outstanding years. This further indicates that the institutional credit sector is now at the forefront of credit delivery with RRBs leading the pack in terms of achievement of credit obligation set by the institutions. However, RRBs being the only institutions to full achieve their target does not mean their contribute more in credit delivery.

CONCLUSION

Lending institutions play an important role in the development of Indian agricultural economy through the providing credit to farming households. Non-institutional sector was the primary source of agricultural credit in the early years, particularly during the pre-independence and early post-independence era, where moneylenders were extorting the rural populace by charging exorbitant interest rates for providing credit. The establishment of institutional credit sector brought an end to the scenario and since then, institutional credit sector has taken over at an increasing pace, the delivery of agricultural credit to farming households in India. There has been an increasing trend in the disbursement of agricultural credit in recent years due to the creation of pro-farmer policy frameworks and the establishment of credit institutions. The creation of NABARD in 1982, with the enactment of NABARD Act 1981 marks the beginning of new dawn in the agricultural credit industry. Institutional credit sector is now the major source of agricultural credit to farming households with commercial banks leading the pack as the major agricultural credit provider in India. Institutional credit sector is undergoing upward trajectory with outstanding performances by surpassing their credit obligations.

- Acharya, S.S., & Agarwal, N.L. (2016). Agricultural marketing in India. Sixth Edition. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., pp: 309-315.

- Kumar A., Singh, K.M., & Shradhajali, S. (2010). Institutional Credit for Agriculture Sector in India; Status, Performance and Determinants. Agricultural Economics Research Review 23: 253-264.

- Kumar, A., Singh D.K. & Prabhat. K. (2007). Performance of Rural Credit Factors Affecting the Choice of Credit Sources. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 62(3): 297-313.

- NABARD (2019). Annual Financial Report, 2018 – 19. Available online at: https://www.nabard.org/financialreport.aspx?cid=505&id=24

- NABARD (2017). Annual Financial Report, 2016 – 17. Available online at: https://www.nabard.org/financialreport.aspx?cid=505&id=24

- NABARD (2015). Annual Financial Report, 2014 – 15. Available online at: https://www.nabard.org/financialreport.aspx?cid=505&id=24

- Reddy, S.S., Ram, P.R., Sastry, T.V.N., & Devi, I.B. (2004). Agricultural Economics. Revised Edition (2013), pp: 502-511.

- Reserve Bank of India (2019). Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit. Available online at: https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=48149

- Reserve Bank of India (2020). Review of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit. Available online at: https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=48149

- Reserve Bank of India (2008). Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, 2007-2008. Available online at: https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/AnnualPublications.aspx?head=Handbook+of+Statistics+on+Indian+Economy

- Shylendra, H.S. (1995). Farm Loan Waivers: A Distributional and Impact Analysis of the Agricultural and Rural Debt Relief Scheme, 1990. Artha Vijnana 3: 261-275.