207

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Methods: A retrospective cohort study (2006-2020) was conducted at two certified Endometriosis Centers in Berlin. We included 21 patients with a history of LASH who subsequently developed symptomatic DIE of the cervical stump or rectovaginal septum. Data on indications for LASH, clinical presentation, and surgical management of DIE were collected and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

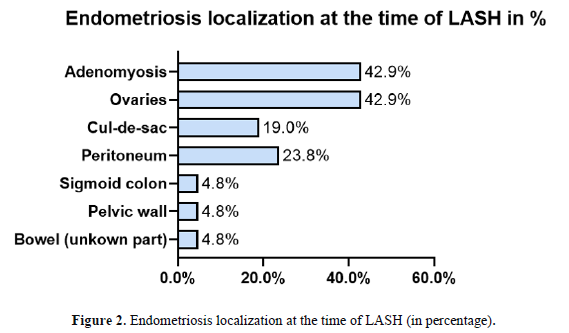

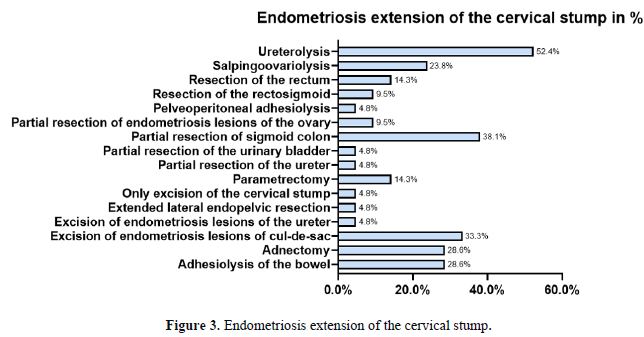

Results: The primary indication for the initial LASH was endometriosis (76.2%, n=16), with 42.9% (n=9) having concomitant adenomyosis. The median time from LASH to clinical suspicion of recurrence was 20 months. The most common symptom leading to re-operation was pelvic pain (80.9%). At surgery, all patients had histologically confirmed DIE. The most frequently affected sites were the sigmoid colon (38.1%), ovaries (33.3%), and cul-de-sac (28.6%). Surgical management was complex, involving ureterolysis (52.4%), partial sigmoid resection (38.1%), and excision of lesions from the cul-de-sac (33.3%).

Conclusion: In this cohort, the majority of patients requiring complex surgery for DIE after LASH had a pre-existing history of endometriosis, suggesting that undiagnosed DIE at the time of LASH is a key risk factor for symptomatic persistence and progression. Thorough preoperative assessment, including advanced imaging such as expert ultrasonography and MRI to exclude DIE, is critical before considering LASH in patients with suspected endometriosis. In cases of known or suspected rectovaginal endometriosis, total hysterectomy with complete excision of all lesions may be a more prudent choice to mitigate the risk of persistent disease and the need for complex re-operation.

Keywords: Endometriosis; LASH, Surgery, Risk Assessment, Cervical Stump, Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LASH) is a well-established minimally invasive procedure for treating benign gynecological conditions, including symptomatic fibroids and adenomyosis [7-11]. The procedure is often chosen over total hysterectomy due to perceived advantages such as shorter operative and recovery times, a potentially lower risk of ureteral injury, and historical assumptions of improved pelvic floor integrity and fewer postoperative sexual complaints [12-16]. Given these perceived benefits, LASH is sometimes extended as a surgical option to patients with endometriosis, particularly when the primary indication is adenomyosis or central pelvic pain believed to be of uterine origin [17].

However, this approach harbors a significant and specific risk for the endometriosis population. By preserving the cervix, the procedure inherently leaves behind the anatomical crossroads where DIE most commonly resides, the posterior cervical stroma, the torus uterinus, and the proximal uterosacral ligaments. In the context of pre-existing, though perhaps unrecognized, DIE, the cervical stump can become a nidus for disease persistence and progression. This can manifest as symptomatic "cervical stump endometriosis," where residual disease infiltrates the rectovaginal septum or surrounding organs, often necessitating a subsequent, highly complex surgery that carries greater morbidity than the initial procedure [7, 14, 18-21]. A recent review reported recurrence rates up to 55% after subtotal hysterectomy in severe disease [22].

Despite this well-understood pathophysiological rationale, the existing literature provides limited granular data on the specific patient profile that develops this severe symptomatic DIE requiring re-operation after LASH. Key questions regarding original indications, time to recurrence, and complexity of re-operation remain unanswered.

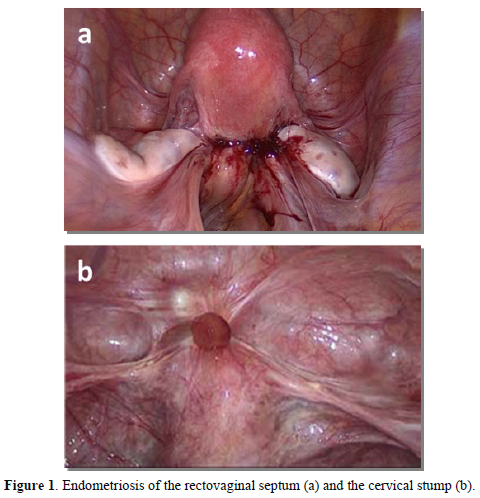

Therefore, this study aims to retrospectively analyze a cohort of women who required complex surgical management for DIE involving the cervical stump or rectovaginal septum following a previous LASH (Figure 1). Our objectives were to delineate their clinical characteristics, primary surgical indications, and re-operation outcomes, with the goal of identifying risk factors and optimizing patient selection for LASH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted between 2006 and 2020 at two certified Endometriosis Centers: Charité-University of Medicine Berlin and Vivantes-Humboldt Clinic in Berlin. Both centers specialize in the diagnosis and surgical management of endometriosis.

Study Population

The study included 21 women who had undergone LASH at external hospitals and subsequently presented with symptomatic DIE of the cervical stump or rectovaginal septum. Inclusion criteria were: (i) history of LASH (2006-2020); (ii) subsequent development of histologically confirmed DIE of the cervical stump/rectovaginal septum; and (iii) available surgical data. Exclusion criteria included major pelvic surgery prior to LASH.

Data Collection and Variables

Data were extracted from medical and surgical records. Collected variables included patient demographics, primary indication for LASH, preoperative hormonal therapy, histopathological findings from the initial surgery, time interval from LASH to symptom recurrence, symptoms leading to re-operation, intraoperative findings at re-operation (DIE localization), surgical procedures performed during re-operation, operative time, and intraoperative complications.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.0.0). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, mean, median, standard deviation) were used to summarize data. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for group comparisons, with a p-value

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Charité University Human Research Ethics Committee (EA1/042/24). Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study, and all data were anonymized before analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Indications for Initial LASH

The population characteristic of the 21 women recruited for this study are summarized in (Table 1). At the time of LASH, the mean age was 39.2 years (range 33-48). The primary indication for LASH was endometriosis in 76.2% (n=16) of cases.

Among these, histopathology revealed concomitant adenomyosis in 9 patients (56.3% of those with endometriosis; 42.9% of total cohort). Uterine fibroids were the primary indication in 38.1% (n=8), and bleeding disturbances in 9.5% (n=2). Notably, none of the LASH surgical reports described DIE lesions. Based on available surgical reports, all cases were classified as rASRM stage I-II; no #ENZIAN classification was documented.

Table 1. Patients Characteristics

|

# |

Indication |

Endometriosis type |

Age when… was performed |

Hormone treatment when LASH was performed |

Classification |

||||

|

LASH |

Extirpation of the cervical stump and resection of DIE |

before LASH |

after LASH |

LASH |

Extirpation of the cervical stump and resection of DIE |

rASRM |

ENZIAN |

||

|

1 |

Bleeding |

Pelvic pain, bleeding |

NI |

Cervical stump endometriosis on its own |

48 |

49 |

Yes |

1 |

NI |

|

2 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain, dyspareunia, hematochezia |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

35 |

37 |

Yes |

3 |

A0B2C0FI |

|

3 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis interna + externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

34 |

36 |

Yes |

1 |

A1B1C0 |

|

4 |

Uterus myomatosus and Adenomyosis |

Bleeding, hematochezia |

NI |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

37 |

39 |

No |

2 |

A1B1C3FAFI |

|

5 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain, dysuria, dyschezia |

Endometriosis genitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

42 |

44 |

No |

4 |

A2B3C0FU |

|

6 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain, bleeding |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

48 |

49 |

No |

NI |

NI |

|

7 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Bleeding |

NI |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

37 |

41 |

No |

4 |

A1B3C3FUFI |

|

8 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain |

NI |

Endometriosis extragenitalis |

34 |

37 |

No |

1 |

A1B1C0 |

|

9 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

38 |

45 |

na |

1 |

A1B0C0FI |

|

10 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis interna + externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

40 |

41 |

No |

1 |

NI |

|

11 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain, dyspareunia |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

38 |

45 |

No |

2 |

A2B2C1 |

|

12 |

NI |

Bleeding |

NI |

Cervical stump endometriosis on its own |

46 |

48 |

No |

1 |

NI |

|

13 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain, bleeding |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

35 |

37 |

Yes |

1 |

NI |

|

14 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain, bleeding |

Endometriosis genitalis interna + externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

37 |

42 |

Yes |

2 |

A2B1C2 |

|

15 |

Endometriosis |

Bleeding |

Endometriosis genitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

36 |

36 |

Yes |

4 |

A2B2C2F1 |

|

16 |

Bleeding |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis interna + externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

43 |

44 |

Yes |

2 |

NI |

|

17 |

Endometriosis |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis interna + externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

42 |

43 |

Yes |

2 |

A1B2C2 |

|

18 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

42 |

43 |

Yes |

4 |

A1B1C2FI |

|

19 |

Uterus myomatosus and Adenomyosis |

Pelvic pain, cyclic subileus |

Endometriosis genitalis |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

39 |

43 |

No |

4 |

B3C3F1 |

|

20 |

Uterus myomatosus |

Pelvic pain, dyspareunia, hematochezia, dyschezia |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

33 |

34 |

No |

3 |

A3B3C3FA |

|

21 |

Menometrorrhagie |

Pelvic pain, bleeding, dysuria |

Endometriosis genitalis externa |

Endometriosis genitalis externa + extragenitalis |

39 |

44 |

Yes |

4 |

FB |

Time to and Presentation of Symptomatic Persistence

The median time from LASH to clinical suspicion of recurrence was 20 months (range 9-85, mean 31.5). The most common symptom leading to re-operation was pelvic pain (80.9%, n=17). Additionally, 42.9% (n=9) experienced regular bleeding from the cervical stump. Other symptoms included dyspareunia, hematochezia, dysuria, and dyschezia.

Surgical Findings and Management at Re-operation

All 21 patients had histologically confirmed DIE. The distribution of DIE lesions is detailed in (Figure 2). The sigmoid colon was affected in 38.1% (n=8), the ovaries in 33.3% (n=7), and the cul-de-sac in 28.6% (n=6). The rectovaginal septum was involved in 38.1% (n=8). Surgical management was complex (Figure 3), frequently involving ureterolysis (52.4%, n=11) and partial sigmoid resection (38.1%, n=8). The mean operative time was 180.25 minutes (median 159, range 43-366). One major intraoperative complication was noted: a lesion of the common iliac vein (4.8%).

DISCUSSION

This case series of 21 patients demonstrates that the need for complex re-operation for DIE after LASH is predominantly associated with a pre-existing history of endometriosis. Our key finding is that the vast majority (76.2%) had a pre-existing diagnosis of endometriosis at the time of their initial LASH. The short median time to re-operation (20 months) strongly suggests that for these patients, LASH represented an incomplete cytoreductive procedure, leaving behind active disease that subsequently persisted and progressed to symptomatic DIE, rather than representing a true de novo recurrence [20, 22]. This short interval further implies that DIE lesions were likely present, though unrecognized, during intital surgery. The clinical course of our cohort aligns with literature suggesting that endometriosis significantly elevates the risks associated with cervix preservation. For instance, while persistent cyclic bleeding occurs in only 5–10% of patients after LASH in the general population [23] it affected 42.9% of our patients.

The high prevalence of pre-existing endometriosis in our cohort aligns with the pathophysiological rationale that preserving the cervix inherently risks leaving disease in the critical crossroads of the rectovaginal septum, torus uterinus, and proximal uterosacral ligaments [7, 22]. Our findings are consistent with literature reporting high relapse rates after subtotal hysterectomy for endometriosis [21, 22]. More directly, a prior case-control study identified a history of endometriosis as a key risk factor for requiring subsequent trachelectomy [24] which mirrors our finding that the preserved cervix became a nidus for symptomatic DIE necessitating complex re-operation. It has been theorized that the retained endometrial tissue from the cervical stump increases risk of reoccurrence through retrograde menstruation [24]. The complexity of the re-operations in our series, with high rates of bowel resection (38.1%) and ureterolysis (52.4%), mirrors the findings of Fedele et al. [25], who emphasized that complete remission of DIE requires the removal of all lesions, a goal inherently compromised when the cervix and surrounding parametrial tissues are preserved.

A critical, and seemingly paradoxical, finding of our analysis is that despite endometriosis being the primary indication for LASH in 76.2% of cases, none of the initial surgical reports described DIE lesions, and all were classified as rASRM stage I-II. This discrepancy is a cornerstone of our interpretation. We posit several non-mutually exclusive explanations. First, the lack of standardized preoperative imaging (e.g., expert ultrasonography or MRI) and the absence of a structured classification system like #ENZIAN in the original reports likely led to a profound underestimation of disease extent. Second, hormonal treatment, which was ongoing in nearly half (10/21) of our patients at the time of LASH, is known to reduce the size and inflammatory activity of endometriotic lesions [26, 27] , potentially masking the true infiltrative nature of the disease from the operating surgeon. Finally, the fact that the initial LASHs were performed at external, non-specialist centers may have contributed, as expertise in recognizing and meticulously mapping the complex presentation of DIE is not universal and is crucial for complete excision [28, 29].

These findings have direct clinical implications. The principle of endometriosis surgery is the complete excision of all visible lesions. LASH, by definition, preserves the cervix and the central posterior pelvic compartment a primary site for DIE. Therefore, performing LASH on a patient with known or suspected endometriosis inherently risks leaving disease behind. Our data strongly suggest that this is not a theoretical risk but a frequent clinical outcome, resulting in complex re-operations. We propose that LASH should be approached with extreme caution in these patients. A thorough preoperative workup is mandatory, including a detailed rectovaginal examination, expert ultrasonography, and preferably MRI to rule out DIE. The use of the #ENZIAN classification is highly recommended for comprehensive documentation and surgical planning. In cases where DIE, particularly of the rectovaginal septum or uterosacral ligaments (ENZIAN C, FA, FB), is identified or strongly suspected, total hysterectomy with complete excision of all lesions should be considered the standard of care to mitigate the risk of persistent disease and the morbidity of subsequent complex surgeries. Patients must be counseled preoperatively about these specific risks associated with cervix preservation.

We must acknowledge several important limitations of our study. Its retrospective design and small sample size limit the generalizability of our findings and preclude broad statistical conclusions. This is particularly relevant when contextualizing our results against large-scale analyses that have established the superior short-term safety profile of LASH, including lower overall complication and surgical site infection rates compared to total hysterectomy [30, 31]. Our study, by focusing on a specific, high-risk cohort that failed initial surgery, reveals a divergent, long-term risk not captured by those datasets. Furthermore, the lack of a control group (e.g., patients with endometriosis who underwent total hysterectomy) prevents direct comparison of recurrence rates. Our reliance on external surgical reports, which lacked detail and standardized staging, introduces potential information bias. A significant limitation is our incomplete data on postoperative hormonal management after LASH. While we know 10 patients were on hormones at the time of LASH, we lack data on whether therapy was continued or discontinued postoperatively. This is a critical confounder, as the cessation of effective suppressive therapy could directly contribute to the progression of residual lesions

CONCLUSION

In this cohort, the need for complex re-operation for DIE after LASH was predominantly associated with a pre-existing history of endometriosis, likely with undiagnosed deep infiltrating disease. These findings caution against the routine use of LASH in this patient population without exhaustive preoperative assessment to exclude DIE. In the context of rectovaginal endometriosis, total hysterectomy may be a more appropriate surgical strategy to prevent recurrence and the morbidity of subsequent complex surgeries. The fundamental issue highlighted by our data is a procedural mismatch: LASH is inherently a 'uterus-centric' intervention, while endometriosis is, by definition, an 'extra-uterine' disease. Performing a procedure that treats the uterus for a condition that exists outside of it logically predisposes to failure. However, future prospective, controlled studies are needed to validate these observations and refine patient selection criteria.

DECLARATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONTRIBUTORS

B.K., A.D.E., V.C., and S.M. conceived the study. A.L., R.V.V., and J.N. were involved in protocol development, gaining ethical approval and data analysis. A.L, R.V.V wrote the initial draft and S.P. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING

The authors declared that this study received no financial support.

CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The Author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study was approved by the Charité University Human Research Ethics Committee (EA1/042/24). Written patient informed consent is not required in retrospective studies.

DATA SHARING

No data is available for sharing.

TRANSPARENCY

The authors affirm that the manuscript provides an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the planned study (and, if applicable, registered) have been explained.

-

Mechsner S (2022) Endometriosis, an Ongoing Pain-Step-by-Step Treatment. J Clin Med 11(2): 467

-

Velho RV, Werner F, Mechsner S, Endo Belly (2023) What Is It and Why Does It Happen?-A Narrative Review. J Clin Med 12(22): 7176

-

Koninckx PR, Martin DC (1992) Deep endometriosis: a consequence of infiltration or retraction or possibly adenomyosis externa? Fertil Steril 58(5): 924–928.

-

Gruber TM, Ortlieb L, Henrich W, Mechsner S (2021) Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Implications on Pregnancy and Outcome. J Clin Med 11(1): 157

-

Imperiale L, Nisolle M, Noël JC, Fastrez M (2023) Three Types of Endometriosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. State of the Art. J Clinical Medicine 12(3): 994.

-

Guan Q, Velho RV, Sehouli J, Mechsner S (2023) Endometriosis and Opioid Receptors: Are Opioids a Possible/Promising Treatment for Endometriosis? Int J Mol Sci 24(2): 1633.

-

Tchartchian G, Bojahr B, Krentel H, De Wilde Rudy L (2022) Evaluation of complications, conversion rate, malignancy rate, and, surgeon's experience in laparoscopic assisted supracervical hysterectomy (LASH) of 1274 large uteri: A retrospective study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 101(12): 1450–1457.

-

McDonnell JE, Liao C, Levin G, Hamilton K (2024) 11830 A Comparison of 30-Day Postoperative Complications in Minimally Invasive Total Versus Supracervical Hysterectomy for Endometriosis. J Minimally Invasive Gynecology 31(11): S116–S117.

-

Meyer R, Hamilton KM, Schneyer RJ, Levin G, Truong MD, et al. (2025) Short-term outcomes of minimally invasive total vs supracervical hysterectomy for uterine fibroids: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 232(4): 377.e1–377.e10.

-

van der Kooij SM, Ankum WM, Hehenkamp WJ (2012) Review of nonsurgical/minimally invasive treatments for uterine fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 24(6): 368–375.

-

Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK (2014) Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health 6: 95–114.

-

Lieng, M., Qvigstad E, Istre O, Langebrekke A, Ballard K (2008) Long-term outcomes following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG 115(13): 1605–1610.

-

Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C (2001) Long term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG 108(10): 1017–1020.

-

Zobbe V, Gimbel H, Andersen BM, Filtenborg T, Jakobsen K, et al. (2004) Sexuality after total vs. subtotal hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 83(2): 191–196.

-

Beyan E, İnan AH, Emirdar V, Budak A, Tutar SO, et al. (2020) Comparison of the Effects of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy and Total Abdominal Hysterectomy on Sexual Function and Quality of Life. Biomed Res Int 2020: 8247207.

-

Brucker SY, Taran FA, Bogdanyova S, Ebersoll S, Wallwiener CW, et al. (2014) Patient-reported quality-of-life and sexual-function outcomes after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH): a prospective, questionnaire-based follow-up study in 915 patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 290(6): 1141–1149.

-

Berner E, Qvigstad E, Myrvold AK, Lieng M, et al. (2014) Pelvic Pain and Patient Satisfaction After Laparoscopic Supracervical Hysterectomy: Prospective Trial. J Minimally Invasive Gynecology 21(3): 406–411.

-

Andersen LL, ZobbeV, Ottesen B, Gluud C, Tabor A, et al. (2015) Five-year follow up of a randomised controlled trial comparing subtotal with total abdominal hysterectomy. BJOG 122(6): 851–857.

-

Neis F, Reisenauer C, Kraemer B, Wagner P, Brucker S, et al. (2021) Retrospective analysis of secondary resection of the cervical stump after subtotal hysterectomy: why and when? Arch Gynecol Obstet 304(6): 1519–1526.

-

Schuster MW, Wheeler 2 TL, Richter HE (2012) Endometriosis after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy with uterine morcellation: a case control study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 19(2): 183–187.

-

Rizk B, Fischer AS, Lotfy HA, Turki R, Zahed HA, et al. (2014) Recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 6(4): 219–27.

-

Alkatout I, Mazidimoradi A, Günther V, Salehiniya H, Allahqoli L (2023) Total or Subtotal Hysterectomy for the Treatment of Endometriosis: A Review. J Clin Med 12(11): 3697

-

Sasaki KJ, Singh AC, Sulo S, Milleret CE (2014) Persistent bleeding after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Jsls 18(4): e2014.002064

-

Tsafrir Z, Aoun J, Papalekas E, Taylor A, Schiffet L, et al. (2017) Risk factors for trachelectomy following supracervical hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 96(4): 421–425.

-

Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanconato G, Berlanda N, Raffaelli R, et al. (2006) Laparoscopic excision of recurrent endometriomas: long-term outcome and comparison with primary surgery. Fertil Steril 85(3): 694–699.

-

Ferrari F, Epis M, Casarin J, Bordi G, Gisoneet EB, et al. (2024) Long-term therapy with dienogest or other oral cyclic estrogen-progestogen can reduce the need for ovarian endometrioma surgery. Womens Health (Lond) 20: 17455057241252573.

-

Wu H, Liu JJ, Ye ST, Liu J, Li N (2024) Efficacy and safety of dienogest in the treatment of deep infiltrating endometriosis: A meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 297: 40–49.

-

Zeppernick F, Zeppernick M, Wölfler MM, Janschek E, Holtmann L, et al. (2024) Surgical Treatment of Patients with Endometriosis in the Certified Endometriosis Centers of the DACH Region - A Subanalysis of the Quality Assurance Study QS ENDO pilot. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 84(7): 646–655.

-

Bougie O, Murji A, Velez MP, Pudwell J, Shellenberger J, et al. (2025) Impact of Surgeon Characteristics on Endometriosis Surgery Outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 32(8): 709–717.e6.

-

Brown O, Tan JG, Gillingham A, Collins S, Gaupp CL, et al. (2020) Minimizing Risks in Minimally Invasive Surgery: Rates of Surgical Site Infection Across Subtypes of Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. J Minimally Invasive Gynecology 27(6): 1370–1376.e1.

-

Meyer R, McDonnell J, Hamilton KM, Schneyer RJ, Levin G, et al. (2025) Postoperative outcomes in minimally invasive total versus supracervical hysterectomy for endometriosis: a NSQIP study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 311(3): 757–763.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Alcoholism Clinical Research

- International Journal of Clinical Case Studies and Reports (ISSN:2641-5771)

- Journal of Immunology Research and Therapy (ISSN:2472-727X)

- Oncology Clinics and Research (ISSN: 2643-055X)

- Journal of Cell Signaling & Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns

- Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics (ISSN:2474-4646)

- Journal of Spine Diseases