4982

Views & Citations3982

Likes & Shares

Globally, Kenya is mainly known for her dominance in middle-distance and long-distance races, the Rugby Sevens and swimming. The country has also been a dominant force in ladies' volleyball within Africa, with both the clubs and the national team winning various continental championships in the past decades (Bukhala, Kweyu & Benoit, 2017). In the field of athletics since the 1960s, Kenya has produced more world-class athletes, record holders and Olympic Medalists in long distance running especially in 800m, 1500m, 3000m steeplechase, 5000m, 10,000m and the marathons. Kenya’s image on the Global stage is that of great world class and record holding athletes have come from the country. Paul Tergat is renowned global athlete and the first Kenyan world record holder in marathon races from 2003 to 2007. Eliud Kipchoge, the contemporary Kenyan long-distance runner, has been on the global arena since 2003, when he won the 9th World Champions in Athletics for the first time (Ingle, 2021). Kipchoge has clinched the world marathon title consecutively in 2016, 2017, and 2018, setting a world record of 2:01:39 during the 2018 Berlin Marathon. More recently, on October 12, 2019, Kipchoge threw Kenya into the global stage when he dared the under two-hour marathon challenge that was dubbed the ‘INEOS 1:59:59 Challenge’ (Ingle, 2021). Against this backdrop, this paper focuses on sports as a source influence which countries apply in enhancing their various interests on the global stage. This article singles out sports and especially athletics as a power resource which can be converted into meaningful influence and then proceeds to particularly discus how Kenya has strategically used sports as one of the tools in fostering its tourism industry. It demonstrates how Kenyan sports men and woman have demonstrated this cultural power on the global stage thereby directly or indirectly contributing to tourism in Kenya.

Sports Diplomacy as Source of National Power

The role of sport in diplomacy falls within the framework of the use of power to win hearts and minds of other actors outside the state for the purpose of national interest. Theorists agree that power is central to international relations. Power, is the currency for various forms of transactions on the global stage. Dominantly, realists place the question of power at the core of the frame through which they analyse international politics (Mearsheimer, 2001). Hans Morgenthau (1954: 25) views international politics in terms of struggle for power just as it is the case in all spheres of social relations (Morgenthau, 1954). Carr, 1964 agrees with Morgenthau’s position that power is central to politics. Nye, 2009 defines power as ‘ability to affect others to get the outcomes one wants”. Power may also be defined as the ability to get others do what they would not otherwise wish to do. Power, however, takes many forms.

Broadly speaking analysts have identified two broad categories of power namely, hard power and soft power. The distinction between hard power and soft power was first by brought forward by Nye, 1990. Hard power includes the ability to apply military force, coercion or economic sanctions (Wilson, 2008). Hard power relies on material resources such as the military, weapons, or economic means (Gallarotti, 2011). From a realist perspective the use of force, the threat to use it or even the actual use of it, constitutes hard power (Esherick, 2017). Soft is the opposite of hard power in that it is not coercive. It is immaterial and targets the minds and hearts of the targeted actors. According to Nye, 1990 when one country gets other countries to want what it wants -might be called co-optive or soft power in contrast with the hard or command power of ordering others to do what it wants.

Diplomacy is one of the forms of soft power. Diplomacy, according to Nicolson (1964: 4-5), is “the management of international relations by negotiation; the method by which these relations are adjusted by ambassadors and envoys; the business or art of the diplomatist”. Watson, 1991 defines diplomacy as “the dialogue between states. At the centre of diplomacy is that it is non-conflictual way of communicating with foreign actors with its main aim as communication and representation (Trunkos& Heere, 2017). Diplomacy aims at negotiations; protects the citizens and other interests abroad; promotes economic, social, cultural, and scientific exchanges between states; and manages foreign policy decisions. Traditionally diplomacy involved government communication. However, new diplomatic channels, modes and actors are emerging in the contemporary international relations. Accordingly other forms of diplomatic interactions include educational exchange programs, concerts, or other cultural events have emerged (Trunkos & Heere, 2017).

Sports diplomacy is one of the new forms of diplomacy. It involves representative and diplomatic activities undertaken by sports people on behalf of and in conjunction with their governments. The practice is facilitated by traditional diplomacy and uses sports people and sporting events to engage, inform and create a favourable image among foreign publics and organisations, to shape their perceptions in a way that is more conducive to the sending government’s foreign policy goals. While traditional diplomacy is the means to a state’s foreign policy ends, sports-diplomacy is the means to the means of those (Murray& Pigman, 2014).

Countries have used sporting activity as a diplomatic tool. This history of sporting activity as an instrument for diplomatic goals is traceable to ancient Greece Olympics, in 776 BC. At its inception, Olympic Games primarily aimed at honouring religious beliefs and Zeus who was considered the father of the ancient gods (Lattipongpun, 2010). Thus the Olympics were primarily a religious festival. Olympia, which lies in north-western corner of the Peloponnese, present day Western Greece region, was a sacred place meant for religious festivals (International Olympic Committee, 2021). Males from all over Greece were allowed to participate, although participants tended to be soldiers. These athletes were mostly sponsored by wealthy aristocrats who were after the glory and fame of their athlete winning an Olympic competition (International Olympic Committee, 2021; Isik, 2020). In its formative periods, the Olympic was a five-day festival combining running, wrestling, boxing, a pentathlon and different types of chariot races. With the establishment of the Olympic Games, a set of rules and traditions were also adopted by the participating Greek city-states (Isik, 2020). After the fifth century B.C., there were major developments of the in the Olympic Games as athletes became highly skilled, dedicated and trained the entire year (Isik, 2020). At this point, the sporting activities were held every four years and would last for up to 3 months. In a tradition that began in the ninth century BCE, an Olympic Truce would be called for this period of time (Isik, 2020).

The diplomatic and political relevance of the Greek Olympic Games is that, during the games, there would be a cease-fire among the Greek-city states participating in the games, both as well as spectators. The games provided an opportunity for peaceful settlement of differences and hostilities among the city states. Further, the Olympic months were a moment for political assemblies and building of alliances. The athletes themselves gained honour, political power and social status from their performance. The relevance in promoting relations among nations was enshrined and perpetuated in the formation of Contemporary Olympic Games initiated in 1894 through the establishment of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in the First Sport Conference in Paris. The first modern Olympic Games were organized in Athens, 1896. (Chatzigianni, 2006). The aspiration of this development was the promotion of olympianism all around the world and expansion of the Olympic Movement (Chatzigianni. 2006). Olympianism refers to a philosophy of life, exalting and combining in a balanced whole the qualities of body, will and mind’. As a transnational organization IOC is primarily characterized by a) being a relatively large, hierarchically organized, centrally directed bureaucracy», b) performing a set of relatively limited, specialized, and in some sense, technical functions, c) performing the pre-mentioned functions across one or more international boundaries and insofar as is possible, in relative disregard of those boundaries, d) has its own interests which inheres in the organization and its functions, which may or may not be closely related to the interests of national groups, e) facilitates the pursuit of a single interest within many national units» and f) requires access to nations (Huntington, 1981; Chatzigianni, 2006).

The IOC is a centrally hierarchical body with an established administrative bureaucratic mechanism, its goal is to promote olympism and the staging of the Olympic Games, transcends national boundaries with access to almost all nations due to its 202 members (Macintosh & Hawes, 1992: 35). The IOC owns the rights to the Olympic symbols, flag, motto and anthem. The Executive Board of the IOC assumes many of the legislative functions of the organization and is responsible for enacting all regulations necessary for the full implementation of the Olympic Charter. The Executive Board is assisted in its administrative function by several commissions, including ethics (including decisions), TV rights and new media, and sport and law. The individual members of the IOC represent the IOC in their respective countries (Georgetown Law Library, 2018).

Today's Olympic Games unite men and women from all corners of the globe, all faiths and all walks of life. World sporting events are seen as great equalizers and a showing of national values, pride and legacies. Countries and regions cultivate national pastimes such as soccer, cricket, weightlifting and martial arts. World powers such as the United States, China and Russia seek imperial dominance and hegemony in the sports arena. International sporting events, like the Olympic Games and World Cup, offer global platforms for rival countries to unite under unprecedented conditions that can improve fraught relations, expose historical divisions, or future conflicts. This event which initiated in the ancient Greece has become a very significant global and part of contemporary global culture. The contemporary Olympic Games bring together participants worldwide with diverse values, cultures. In the contemporary global arena, sporting activities have been used in various ways as an instrument of public diplomacy.

Sports Diplomacy in Contemporary International Relations

Like in the Greek world, sporting in the contemporary world arena has been instrument for lowering conflict temperatures among or between countries. Sports create a platform for states to come together peacefully yet at the same time presents an opportunity to peacefully challenge each other fairly. Sports diplomacy has gradually played important role in diplomatic practice and in global sports industry. Murray, 2016 argues that in the divided world which falsely appears to be increasingly unified, sports especially FIFA Soccer World Cup and the Olympic Games have symbolic value which goes beyond the sporting competition. The common values of sport include activities such as teamwork, competition and fair play. These values are accepted by all actors and for this reason help in bringing people together and building trust among countries. For this reason governments worldwide are using sports to promote peace, prosperity and strengthen international relations. Sporting events offer prospects of enforcing a sense of community, through a set of values. For example, according to Nauright, 2014 the values such as humanity, peace, fair play which are associated with the Olympics are easily transferable between communities as the Olympic Games are ideally aimed at uniting, and founded on the broad liberal values of the Olympic Movement for a unified community, consolidated by the celebration of sport, culture and the environment.

There is a nexus between sports, national visibility, cultural dominance and nationalism in sports competition. Nationalism is a frame of consciousness in which a political community thinks of itself as having a shared origin, culture, history and language. They think of themselves as a people. According to Hans Kohn, 1965, nationalism is ‘a state of mind, in which the supreme loyalty of the individual is felt to be due to the nation state’. Nationalism, according Kohn absorbs the entirety of the person.

It is living and active corporate will. It is this will which we call nationalism, a state of mind inspiring the large majority of people and claiming to inspire all its members. It asserts that the nation-state is the ideal and the only legitimate form of political organization and that the nationality is the source of all cultural creative energy and economic well-being (Kohn, 1965).

The foregoing can be corroborated by Esherick, Baker, Jackson & Sam, 2017 who observe that, sport if used well can be a unifying factor and a tool for collective identity and national unity. In the modern societies, sport has played a critical role in establishing a platform for the citizen to socialize, share belief system and values (Laverty, 2010). In this respect, international sport can be instrumental in bringing a people together in the process of building a divided nation. For example, during the 1994 Rugby World Cup following the end of Apartheid an 'inclusive' theme song, 'Shosholoza', was chosen for the Springbok team in an endeavour to bring together a nation hitherto divided behind the national rugby team (Nauright, 2014). Nauright, 2002 observes that the song was traditionally sung by migrant workers as they travelled from Zimbabwe to work in South African mines. It was a workers’ song sung by men who went to their early deaths in the gold mines. According to Nauright, 2002 this was a central cultural element in the presentation of the new and unified South Africa.

Sport is also relevant to national Unity. The relevance of national unity is that it is a critical determinant of foreign policy of a country. Generally homogeneous societies are stronger in their foreign policies compared to heterogeneous or fragmented societies. And sports in this case can be a contributing factor to national unity. According to Jarvie, 2005 sport is a form of cultural nationalism, political nationalism, ethnic, as well as civic forms of rationality. It can help in national recognition and provides a way through which a society can express its frustrations. This makes sports a form of social consciousness (Jarvie, 2005). Besides sports offering a golden opportunity to see how individual, national, and global factors together affect national identities (Skey, 2013). World sporting events are seen as great equalizers and a showing of national values, pride and legacies. Specific countries and regions cultivate national pastimes such as soccer, cricket, weightlifting and martial arts, while world powers such as the United States, China and Russia seek imperial dominance and hegemony over the sports arena. Nonetheless, international sporting events, like the Olympic Games and World Cup, offer global platforms for rival countries to unite under unprecedented conditions that can improve fraught relations, expose historical divisions, or foresee future conflicts.

Leaders have used sports to express their extreme forms of nationalism. For example, it is recorded in history that, Benito Mussolini used the 1934 FIFA World Cup, which was held in Italy, to display Fascist Italy (Blamires & Cyprian, 2006). Adolf Hitler also used the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin, and the 1936 Winter Olympics held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, to promote the Nazi ideology of the superiority of the Aryan race, and inferiority of the Jews and other “undesirables“ (Blamires, 2006; Saxena, 2001). During the Cold-War USSR endeavored to excel on the international sports arena as a way displaying its power (Murray, 2012). Given the significance of sports on the global stage, it also been used an instrument for deterrence or sanction. For example, during the apartheid era in South Africa the country was excluded from taking part in world sporting activities such as rugby and soccer. In so far as South African teams were degradative in their formation in line with apartheid policy, these teams were not considered legitimacy South Africa. This was a way of reinforcing international human rights principles outlawing the crimes of apartheid while encouraging none-racialism (Murray & Merrett, 2004).

Sports Diplomacy and its Implication on Tourism Industry in Kenya

The foregoing discussion focuses sports diplomacy generally; we now turn our focus on sports diplomacy and tourism. With globalization and revolution in information and commination technology sporting, as a national resource, has been raised to greater heights within countries. Sport itself has become one of the drivers of globalization. John Nauright, 2014 observes that ‘sport has assumed an ever greater role within the globalization process and in the regeneration of national, regional and local identities in the postcolonial and global age. Nauright, 2014 observes further that through the media, significant sporting events such as the Olympic Games or the FIFA soccer World Cup have become highly attractive commodities and economically powerful countries are moving towards event-driven economies.

In this respect and within the thinking of sports nationalism, economically powerful countries invest in competitive international elite sporting programmes that can generate greater returns as countries position themselves in the global hierarchy of nations (Grix, & Carmichael, 2011). From the early 2000s media corporations have invested at unprecedented levels in sporting coverage and team/league ownership. Particularly pay television companies have become global entities and media corporations sought cheap and ready-made programming which they sell across the world (Nauright, 2014). Global companies have invested in paid for channels such as DSTV which make profits through broadcasting of global sports. The point is that sports and sporting activities have become constitutive elements of contemporary global political economy, a mode of production manifested on the world stage in terms of 'branding', 'theming' and consumption of image and lifestyle observed in domestic, regional as well as global tournaments like the Olympic Games and the FIFA world Cup (Nauright, 2014). Sporting events have become factors and strategies in local and national development planning. This is the case in Kenya as elsewhere.

Sporting in Kenya is traceable to traditional societies that make the present day Kenya. The people were actively involved in traditional sporting activities even before colonialism. Some of the traditional sporting activities included traditional archery, hunting and wrestling which were restricted within the indigenous communities (Simiyu, 2010). Sporting activities in the traditional Kenyan societies were aimed at holistic wellbeing of members of the society including physical, political, social, moral and even economic (for instance hunting and fishing). Sports in traditional Kenyan communities (and probable the case in many African societies) enshrined many things such as patriotism, discipline, leisure, performance and preservation of identity.

With advent of colonialism, the values of games in traditional Kenya were transformed, and to some extent later dismissed as primitive with the coming of colonialism. Colonialism transformed the character of the sporting arena as indigenous sports were considered as primitive as the goal of sporting became part of civilizing mission (Hübner, 2015). New sports were introduced such as horse racing, golf, polo, tennis cricket, soccer, boxing and athletics. However, these sports were purely for the European settlers except boxing and athletics (Mählmann, 1988; Simiyu, 2010).

African Studies Center (ASC) at Michigan State University (n.d.) notes that colonialism introduced European forms of sports and games to Kenya while traditional ones were often discarded as primitive. New sports from Europe, North America and Asia often performed along racial lines were imposed in Kenya. The British introduced tennis, cricket, rugby, and soccer in the 1920s as American missionaries introduced basketball in the 1950s (African Studies Center (ASC) at Michigan State University, n.d.). Games like rugby and tennis were strictly for whites and hockey was reserved for Kenyans and Indians. There was also the introduction of sports in schools in 1925.

Kamenju, Rintaugu & Mwangi, 2016 argue that there was a quick adoption the western sports by the African people who were passionate with athleticism and physical movement culture. Sports such as athletics and boxing were quickly picked up by Africans. The African Studies Center (ASC) at Michigan State University (n.d.) further highlights the development of physical education curriculum for schools that focused on the teaching of modern sports, and introduction of competitive sports in schools, communities and at the international levels in the 1950s. Open spaces were set-aside in urban and rural areas to accommodate sporting activities.

Kenya entered into the world competitive athletics through the formation of the Kenya Amateur Athletic Association (KAAA) in 1951. Following this formation Kenya participated in Indian Ocean Games in 1952 in Madagascar and Commonwealth Games in 1954 Canada (Anderson, 2017). In 1956 Kenya participated in international competitions of the Olympic Games held in Melbourne, Australia. Though Kenya did not win any medal in these competitions the achievement in two games created the opportunities for the Kenyans distance runners to subsequently dominate world athletics (Simiyu, 2010). In 1964 Wilson Kiprugut Chumo won a bronze medal in 800m at the Tokyo Olympic Games (Tanui, 2015). The winning of the bronze medal created further created enthusiasm and passion among the Kenyan runners and in 1968 during the Mexico Olympic Games, Kenyan runners overwhelming won medals in middle and long distance races (Ouko, 2018).

At the same time, at the 1968 Olympic Games, Kenyans started dominating 3000m steeplechase for men. Since 1968, Kenya athletic men/women have consistently won gold medals in the 3000m steeplechase in every Olympic Games (Njororai, 2010; Pitsiladis, Onywera, Geogiades, O’Connell, & Boit, 2004). Bale & Sang, 1996; Tulloh, 1982 agree that the 1960s success was as a result of the country having home-based runners all of whom were either in schools or from the military. It was because of the great success at the 1968 that exposed Kenya to a global audience. This resulted into the enormous transfer and admission of many talented Kenyan runners into US universities. This probably led to the emergence of migration of the Kenya’s athlete not only to the US but also to other parts of the world.

However, in 1983, Kenyan secured its first victory in a world-class marathon. This happened when Joseph Nzau, US-based won the Chicago Marathon. In 1985, Ibrahim Hussein, who by then was a fresh from the University of New Mexico, also won the Marathon. Hussein achieved three consecutive victories in Honolulu, New York City, in 1987 and in Boston in 1988, 1991 and 1992 respectively. This made him one of the most successful marathon runners from Kenya. In addition, Douglas Wakiihuri, a Japanese-trained marathon runner won several championships such as; Track and Field World Championships in 1987; a silver medal during the Olympic Games in 1988; a London Marathon in 1989 and the New York City Marathon in 1990. From 2018 and in the years that followed Kenya remained the record holder of world marathon champion won by Eliud Kipchoge in 2018 Berlin Marathon.

Kenya's sportsmen and sportswomen have played a leading and to some extent, unrivalled role of bringing about popularity and publicity of the country on the international scene, registering remarkable international recognition. The aspect of sport as a tool of bringing about national popularity and recognition is one aspect of social development which has brought pride and international recognition to Kenya. Indeed, arising from the numerous successes registered by Kenya's sports activities. In 1956, when Kenya took part in the Olympic Games for the first time, the country secured a lot of recognition from many countries around the world (Ouko, 2018). According to Athletics Kenya (2014), the pioneers of medals in Kenyan sports scene were Bronze medallist kipkurugut Wilson; Gold Medallist Naftali Temu; Gold Medallist Kipchoge Keino; Gold Medallist Amos Biwott; Silver Medallist Benjamin Kogo; Silver Medallist Daniel Rudisha, and Silver medallist Munyoro Nyamau. All these according to Athletics Kenya were won in 1968 Olympic in Tokyo Japan in different competitions.

Another event that Kenyans featured prominently, and contributing to Kenya’s visibility, in post-independence was the Boston Marathon. Ibrahim Hussein won the first of his three Boston Marathon victories in 1988, less than a year after winning the New York City Marathon. Hussein had back-to-back victories at Boston in 1991-92. Kenyan men broke the tape at the Boston Marathon 20 times between 1988 and 2000. Korir highlights further that Kenyan women had 10 victories at Boston. Other notable winners were Cosmas Ndeti, (1993-95), Moses Tanui, a two time winner in 1996 and 1998; Robert Cheruiyot, with four victories (2003, 2006; 2008); Catherine Ndereba, a four time winner in the women‘s division; Geoffrey Mutai, 2011; Rita Jeptoo, 2013. Records show emergence of sons and daughters of former Medalists. These in include, for example, Eliud Kipchoge who won Bronze medal in Athens in 2004, and Gold medallist David Rudisha in London 2012 among others.

One of the significant sporting events that placed Kenya on the global was the hosting of the 4th All-Africa Games in Nairobi in 1987. The event convened at the Moi International Sports Center, in Kasarani, Nairobi. The facility was developed through the Chinese bilateral assistance that supported the construction of Moi International Sports Center, in Kasarani, Nairobi, from 1983 to 1987 in preparation for the fourth All African Games held in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1987. This event is considered a significant attraction of tourists and foreign investors to the country whose main aim has been to intermingle with the athlete’s heroes, compete alongside them and or learn from them. This provided an opportunity for diplomatic interaction between Kenya and other African countries. It contributed to Kenya’s presence on the global map. Apart from the athletes, the event attracted international media who were covering the event as Kenya featured is such media coverages.

Significantly, Kenyan athletes have won international accolades in the world of sports. This has contributed to bolstering the presence of Kenyan on the global stage. Just to highlight a few, Paul Tergat was globally honoured as the first Kenyan to set a record in the world marathon races from 2003 to 2007. In honour of these accomplishments Paul Tergat was feted with the 2010 Abebe Bikila Award, making him the first Kenyan male to receive the award. Tergat was the second Kenyan ever to have won the award after Tegla Loroupe in 1999. The Abebe Bikila Award, named in honor of the two-time Olympic marathon winner Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia, is a yearly prize given by the New York Road Runners club (NYRR) honoring individuals who have made outstanding contribution to long-distance running. This award was first received by Ted Corbitt, a founder of both NYRR and the Road Runners Club of America on October 27, 1978.

Pamela Jelimo won the 800m Olympic title and joined the lucrative Golden League athletics jackpot. Jelimo who was 18 years old at that point, won the 800 meters in 55.16 seconds, more than three seconds ahead of compatriot Janeth Jepkosgei and third-placed Kenia Sinclair of Jamaica. With a devastating sprint, Pamela Jelimo claimed the Golden League's $1 million jackpot. Another outstanding athlete in Kenyan history of athletics is Eliud Kipchoge, a long-distance runner, who has been on the global stage since 2003 when he won the 9th World Champions in Athletics for the first time. Kipchoge subsequently won world marathon title in series in 2016, 2017, and 2018. In the 2018 Berlin Marathon he set a world record of 2:01:39. In October 12, 2019, Kipchoge boldly placed Kenya into the global stage when he competed with time for under two-hour marathon challenge, ‘INEOS 1:59:59 Challenge’ in Austria, as already been mentioned elsewhere in this paper. The event was not considered a world record due to the conditions of the race. However, Eliud was celebrated globally by renowned world leaders and sports lovers as the greatest marathoner of the modern era’. The build-up to the rare feat and the actual event captured the world’s imagination, with hundreds of thousands of sports enthusiasts from all over the world travelling to the popular European capital (Okeyo and Rutto, 2019). An indication of the global achievement Eliud Kipchoge’s was President Obamas remark: ‘Yesterday, marathoner Eliud Kipchoge became the first ever to break two hours. Today in Chicago, Brigid Kosgei set a new women’s world record. Staggering achievements on their own, they’re also remarkable examples of humanity’s ability to endure and keep raising the bar’ (Obama, 2019). At the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, Eliud Kipchoge cemented his legacy as the greatest marathon runner (Mohammed, 2021).

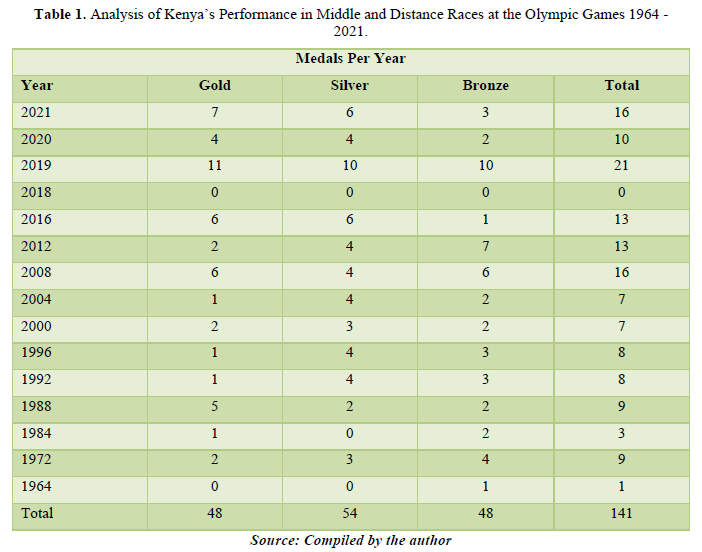

The Olympics Games is one area where Kenya has consistently excelled in decades, raising Kenyan stature on the global map. Below is a summary of Kenyan achievements in the area of Olympic Games across decades (Table 1).

Another significant point to note is that, Kenya competes with global powers and indeed outshines many of them in the field of athletics, especially in middle and long distance races. For example CGTN Africa (2019) reports that Kenya finished second behind USA in the 2019 IAAF Athletics World Championships in Doha, Qatar. Kenya concluded the biennial competition with a total of 11 medals - five gold, two silver and four bronze medals. The United States topped the medal standings with 29 medals. Jamaica finished third with 12 medals, followed by China (9 medal) and Ethiopia, who wrapped up the top five slots with eight medals. CGTN Africa (2019) further indicates that, during the 2017 IAAF Athletics World Championships in London, Kenya won the exact total number of medal in the same order and also came second to the United States (CGTN Africa, 2019). This places Kenya strongly on the global map against global powers. It suffices to note that what is highlighted above does not in any way represent that full record on Kenyan dominance and achievements in the world of athletics. However, it goes so far to indicate that athletics is a significant area through which Kenya’s visibility on the global stage can be enhanced.

These performances at the international stage have put the country on the global map contributing to national interests among which include tourism. There is a close connection between sport diplomacy and tourism in general and sport tourism in particular. Sports diplomacy promotes Kenya’s political image and economic interests. Sports tourism refers a myriad of activities sporting activities for commercial goals (De Knop and Standeven, 1999). These activities include hosting games, building stadia and enhancing the participation of their recognized sports persons to generate income for the country (Mwongeli, 2019). From this perspective the myriad of initiatives by countries to enhance sporting and related activities in their countries boil down to sport tourism.

From the perspective sport tourism, Kenya has used safari rally to attract sports enthusiasts and competitors to the East African Safari Classic rally (Andiva, 2018). The safari rally started in 1953 as the East African Coronation Safari, a celebration of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. It first happened with three starts between Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Kenya has a good landscape for high altitude training, canoeing, golf, and kayaking. Hotels and tourism industry greatly benefit from this. Adventure camps have capitalized on these experiences and do provide services to help tourists navigate through the landscape.

Sports, and particularly athletics, in the context this this discussion, has great capacity to market a country and attract tourists in the form spectators, fans, researchers, trainers and trainees. In this regard Kenya stands at vantage point vis-à-vis its rivals in the global market (Mbasi, 2006). The dominance of Kenyan athletes on the global tracks raises curiosity in the minds of admirers, competitors, spectators, commentators and researchers on the kind country that produces such great performers. Some Universities outside the African continent have research portfolios to undertake investigation the phenomenon of uniquely talented long distance and middle range runners from the East Africa region. A good example is the International Centre for East African Running Science, Faculty of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow in the United Kingdom. Indeed there are debates as to why the region produces the best long distance athletes in the world, a puzzle that has the potential of attracting foreign sports researchers and athletes to visit the region to try to provide an explanation. The desire to have this scientific understanding further aroused the curiosity of even other athletes from around the world. Researchers have dedicated their attention on the success of the runners to understand factors that may explain their success such as how they train, what they eat and how they live (Espien, 2013; Onywera, 2009; Scott & Pitsiladis, 2007).

Particularly, runners from across the world travel to North Rift region of Kenya, colloquially known as the ‘the home of champions’, eager to learn why the country is such a dominant force in the middle and long-distance running. Foreign athletes, spectators and researchers travel from different parts of the world to come to train, spectate or undertake research in the North Rift region of Kenya. This is the region where, though not entirely, outstanding athletes come from. The North Rift is a high altitude zone which provides for conditions for training for the world best long distance runners. This makes the region attractive to tourist as a natural site for tourism. The natural resources of a destination physiography, climate, flora and fauna, scenery and other physical assets functioning as a source of competitive advantage, a destination’s endowment of natural resources is crucial for many forms of tourism and visitor satisfaction and define the environmental framework within which the visitor enjoys the destination (Buckley, 1994; Dunn & Iso-Ahola, 1991).

Runners find out that the region provides a good topography and environment for athletics training due to its high altitude which can be hailed for production of world-runners. The high altitude areas of Iten and Eldoret provide good grounds for athlete training and an opportunity to train with Kenyan athletic champions (Mwongeli, 2019). The high-altitude town of Iten, region within Kenya’s Rift Valley, attracts both professional and amateur runners from around the world. The stunning location offers a perfect backdrop for a world-class athletics experience (Kimeto, 2021).

The training by the international athletes with the local athletes in Kenya has in turn kindled a vigorous following of the sport in Kenya and further generating increased international attention. This attraction made manufacturing companies like shoe such as Nike, Adidas and Puma to start investing in sporting materials for athletes. More particularly, some of the best runners across the world have trained in the region, including Britain’s Mo Farah, previous world women’s marathon record holder Paula Radcliffe, 2012 Olympics 800m silver medallist Nijel Amos as well as New Zealand twins Zane and Jake Robertson. Swiss Jullien Wanders, the European record for the half marathon with a time of 59:13, also lived and trained in the North Rift for the past four years. Apart from the elite runners, hundreds of social runners also visit the country and train with Kenyan world champions as sports tourists.

Kenya’s sports diplomacy has made possible development projects, job creation, infrastructure development, sports sponsorships, investments and sports tourism. Funds generated from hosting international events, transfer fees, entry fees, taxes, training fees, sports tourism, tenders and sports equipment procurement, all lead to economic growth of Kenya’s economy. The counties of North Rift are endowed differently with a huge comparative advantage exemplified by the colossal amount of athletic talent and opportunities (Kipchumba, 2018). These observations demonstrate the intricate link between sport diplomacy and tourism.

CONCLUSION

Kenya is a society endowed with sports capacities especially in athletics which stands out as a significant power resource. Sports arena provides leverage for diplomatic relations even between the most power and the relatively less powerful. By bringing together people of different races, cultures, and nations, sports has that capacity of neutralizing perceived differences. Sporting activities allow countries to achieve visibility on the global stage. Kenya has remarkably entrenched itself in world of sports especially in the field of athletics with significant achievements which rival powerful nations. Kenya has also developed sports infrastructure, membership of international sports organizations, and attempted to integrate sports within diplomatic missions. Remarkable practice of cultural diplomacy has been displayed by Kenyan athletes at the global sporting arena since Independence. Kenyan boasts of Athletics which is part of its cultural resources through which it has dominated the global stage and to a significant extent placed itself on the global stage. The athletes have remarkable projected Kenya’s image on the global stage. Through their actions they are seen, identified, recognized as Kenyans. They make Kenya exist in the eyes or minds of other states. This shapes the attitude and perception on Kenya and other states during sport interactions. Through their actions, when they participate and excel on the global stage they promote other interests such as economic interests. Kenya being an incredible tourist destination has benefited from sports diplomacy by attracting sport tourists to benefit from Kenya’s sports resources thereby enhancing the country’s tourism industry.

Buckley, R. (1994). A Framework for Ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research 21 (3), 661-669.

Peter, B., Kweyu, I., & Benoit, G. (2017).Socio Cultural Determinants of Athletics Abilities among Kenyan Elite & Sub-Elite Middle and Long Distance Runners IRD Editions. Available online at: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01429296

Carr, H. E., (1946). The Twenty Years Crisis An Introduction to the Study of International Relations. New York; Harper and Row.

Efthalia,C. (2006). The IOC as an international organization. Sport Management International Journal, 2(1-2), 91-101.

De Knop, P., & Standeven, J. (1999) Sport Tourism Champaign IL Human Kinetics.

Dunn, R. & Iso Ahala, S. (1991). Sightseeing Tourists Motivations and Satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research 18(2), 226-37.

Epstein, D. (2013). The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance. Westminster UK; Penguin.

Esherick, C., Baker, R. E., Jackson, S. J., & Sam, M. P. (Eds.). (2017). Case Studies in Sport Diplomacy. Fit Publishing, A Division Of The International Center For Performance Excellence, West Virginia University.

Gallarotti, Giulio M. (2011).Soft power what it iswhy its important, and the conditions for its effective use, Journal of Political Power ,4(1), 25-47.

Georgetown Law Library (2018), Olympics and International Sports Law Research Guide Georgetown Law, Available online at: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=364665&p=2463479.

Grix, J. & Carmichael, F. (2011). Why do governments invest in elite sport A polemic, pp: 73-90. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2011.627358/

Hübner, S. (2015). Muscular Christianity and the Western Civilizing Mission in Diplomatic History, 39(3), 532-557

Sean,I. (2021). Kenyas Eliud Kipchoge blitzes field for second straight Olympic marathon gold. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/aug/08/kenyas-eliud-kipchoge-blitzes-field-for-second-straight-olympic-marathon-gold/

International Olympic Committee (2021). Olympic History-from the home of Zeus in Olympias to the Modern Game. Available online at: https://olympics.com/ioc/ancient-olympic-games/history/

Işik, Arda Alan (2020). Origins of sports philosophy and Greek athletics Daily Sabath. Available online at: https://www.dailysabah.com/sports/origins-of-sports-philosophy-and-greek-athletics/news/

Jarvie, G. (2005).Sport Culture and Society An Introduction. London Routledge.

Kakonge J. O. (2016). Sports in Africa An untapped resource for development Pambazuka News. Available online at: https://www.pambazuka.org/global-south/sports-africa-untapped-resource-development/

Kamenju, J. W., Rintaugu, E. G., & Mwangi, F. M. (2016). Development of Physical Education and Sports in Kenya in the 21st Century An Early Appraisal.

Byron, K., & Rose, J., Thomson, C. (2015). Sports Policy in Kenya Deconstruction of Colonial and Post-Colonial Conditions, International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(2),301-313.

Kimeto, J. (2021) Kericho Tea Can be a Key Tourist Attraction, The Standard. Available online at: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/amp/opinion/article/2001405140/kericho-tea-can-be-a-key-tourist-attraction/

Kohn, Hans (1965). Nationalism, Its Meaning and History. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand.

Lattipongpun, W. (2010).The Origins of the Olympic Games Opening and Closing Ceremonies Artistic Creativity and Communication, Intercultural Communication Studies 19(1), 103-120.

Laverty, A. (2010). Sports Diplomacy and Apartheid South Africa. Available online at: https://theafricanfile.com/politicshistory/sports-diplomacy-and-apartheid-south-africa/

Mählmann, P., (1988).Sport as a weapon of colonialism in Kenya a review of the Literature. Trans African Journal of History, 17, 172-185.

Mbasi, C. (2006). Sports to boost tourism product range.Financial Standard.

Mearsheimer, J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York W.W. Norton.

Mohammed, O. (2021. Athletics Kenyans Kipchoge cements legacy as greatest marathon runner Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/athletics-kenyas-kipchoge-cements-legacy-greatest-marathon-runner-2021-08-08/

Morgenthau, J. H. (1954). Politics among Nations The Struggle for Power and Peace.

Murray, S. (2012). The Two Halves of Sports Diplomacy Diplomacy and Statecraft 23(3):576-592.

Murray, B & Merrett, C. (2005) Caught Behind: Race and Politics in Springbok Cricket. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Murray, S. & Pigman G.A., (2017). Mapping the Relationship between International Sport and Diplomacy Sport in Society, 17, 9.

Mwisukha, A., Njororai, W. W. S., & Onywera, V. (2003). Contributions of sports towards national development in Kenya. East African Journal of Physical Research and Development 23, 160-175.

Mwongeli, M. M. (2019).The Role of Sports Diplomacy in Promoting Kenyas Foreign Policy Goals United States. International University Africa Unpublished thesis.

Nicolson, H. (1964). Diplomacy New York Oxford University Press.

Nye, J. S. (1990).Soft Power Foreign Policy, 80, 153-171.

Nye, J. S.(2009). Understanding International Conflicts. New York Pearson.

Obama, B. (2019). Available online at: https://twitter.com/barackobama/status/1183492717017554944?lang=en/

Okeyo, D. & Ruto, S. (2019) How Kenya Loses Race For Sports Tourism Billions Financial Standard. Available online at: https://Www.Standardmedia.Co.Ke/Business/Financial/Standard/Article/2001345560/How-Kenya-Loses-Race-For-Sports-Tourism-Billions/

Ouko, C. (2018). Mexico City East Africa’s memorable Olympics. The East African. Available online at: https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/magazine/mexico-city-1968-east-africa-s-memorable-olympics-1405778/

Onywera, V.O. (2009).East African Runners Their Genetics Lifestyle and Athletic Prowess Medicine and Sport Science, 54, 102-109.

Saxena, A. (2011). The Sociology of Sport and Physical Education Sports Publication New Delhi.

Scott, R.A & Pitsiladis, Y. (2007).Genotypes and Distance Running Sports Medicine 37(4-5), 424-427.

Simiyu Njororai, W. W. (2012). Distance Running In Kenya Athletics Labour Migration and Its Consequences. Leisure Loisir, 36(2), 187-209.

Simiyu, W. W. N. (2010).Global inequality and athlete labour migration from Kenya. Leisure Loisir 34(4), 443-461.

Michael, S. (2013).Why Do Nations Matter. British Journal of Sociology 64(1), 81-98.

Tanui, N. (2015). Wilson Kiprugut Chumo: Champion who brought first medal to Kenyan Soil. The Standard. Available online at: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/kenya-at-50/article/2000098754/champion-who-brought-first-medal-to-kenyan-soil/

Trunkos, J., & Heere, B., Esherick,C., Baker, R. E., Jackson, S. J.,et al. (2017) Sport diplomacy a review of how sports can be used to improve international relationships. In Case studies in sport diplomacy pp: 1-17.

Watson, A. (1991). Diplomacy the Dialogue between States. London Routledge.

Wilson, E. J. (March 2008). Hard Power Soft Power Smart Power (PDF). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616(1), 110-124.