Research Article

A CONCEPTUAL REVIEW OF THE INITIATIVES OF THE HOST COMMUNITY IN THE PROCESS OF BRANDING TOURISM DESTINATIONS

8907

Views & Citations7907

Likes & Shares

Branding in tourism have been used by most Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) to keep destinations lingering in the tourism competitive market. Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) are using branding as a weapon to build their image during the pre-Covid 19 periods in the ever-competitive tourism industry and will continue to do aftermath Covid-19 pandemic. Most DMOs are using branding as a marketing ploy to attract visitors. However, to build a pronounced brand on a sounder footing and improve the branding process, the role of the host community has been overlooked by Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) leaving most scholarly articles looking at the role of the host community in developing tourism products (Yu et., 2011), implementing sustainable tourism, and ecotourism (Israr, 2009) rather than creative a positive brand image. As such, it appears through an analysis of literature that there is insufficient detailed comprehensive conceptual review of the role played by the host community in the branding process. This paper, therefore, seeks to provide a conceptual review of the role of the host community in the branding process. The paper is based on an extensive review and analysis of existing literature which includes popular journals, websites, academic peer-reviewed journals and other related scholarly works. The researcher provides a descriptive and critical evaluation of the role of the host community in branding tourism destinations. The paper finds out that the host community provides several covert and overt benefits which include, among others, building destination brand image, enhancing brand knowledge, improving brand responsibility and participation, evoking brand loyalty and creating brand awareness. These benefits make the host community to stand alongside others best branding stakeholders.

Keywords: Destination, branding, destination branding, host community.

There is a preponderance of literature that supports the notion that there is “hard competition” among tourism destinations as they continue to provide the same intrinsic attributes, that is, superb five-star resorts, attractions, unique culture, friendliest people, and high standard of customer service and facilities (Mujoma, 2010). Destinations are fiercely fighting for tourists’ money (Eghbali et al., 2015).

The hard competition and fierce competition have left the academic domain pondering that the competitive battle for the tourism markets is no longer fought over the price but over the hearts and minds of the people (Morgan, Pritchard, & Pride, 2004) and the future of marketing will be the battle of brands (Steven, 2005). Consequently, destinations across the world are being branded and rebranded to enhance their position as leisure attractions, business and tourism destinations of choice (Ashworth & Kavaratzis, 2015). Despite branding becoming perhaps the most powerful weapon available to contemporary destination marketers and the basis for survival within a globally competitive marketplace (Morgan et al., 2004), it is not clearly clarified what are the initiatives of host communities in the branding process to generate effective brands.

White literature does not clearly state the initiatives of the host community, there is an assertion that to effectively brand a destination, brand managers need to take an all-inclusive or holistic approach considering those who are at the grassroots level to produce effective brands. This is partly because those on the grassroots level are the ones who disseminate information and interact with the tourists. In doing so they play a vital role in the “creative tourism world”. It is, therefore, logical to argue that branding implementation needs inspiration from the host community.

Brands are capable of infusing almost all aspects of tourism service; be it tourist behaviour, tourist choice and destination image hence can be perceived as the catalyst in luring visitors. Despite the importance of branding on destinations, (King, 2010). states that internal brand management especially the influence of host community in branding is yet to be thoroughly explored as an explicit topic (Rehmet & Dannie, 2013). This is attributed to some literature in this field which provides a periphery of the role of host communities on destination branding only focusing on their communication (WOM) (Jeuring & Haartsen, 2017; (Kavaratzis, 2012; Choo & Petrick, 2011). Literature is generally silent with regards to the initiatives of people in the developing country of which most tourists are visiting to experience a culture which is created by the host people. Overlooking of host communities in the branding process is leading to brands that communicate only tacit connection of destinations than the communal meaning and shared habits (Campelo, Aitken, Thyne & Gnoth, 2013). inherited within the host community.

It is indisputable to assert that visitors’ emotions whilst interacting with the local community determines the level of memorable experience (Kavaratzis, 2009). This is partly because host communities are the ones who provide visitors with some of the entertainment and in some cases are in a position to forego their basic needs to accommodate them. Visitors are prepared to pay high prices in accommodative destinations (Kasapi & Cela, 2017). It is therefore of utmost importance for marketers to use brands that are made up of elements of local communities and related local attributes (Stojanovic, Potkovic & Mitkovic, 2012) to entice visitors. This assertion necessitates the need to understand the value or role of the host community in the branding process of destinations.

Against such background, the question is not whether destinations can be branded, but who should be taken into consideration and how do they influence the branding process.

CONCEPTUAL REVIEW

Tourism destination and host community

A tourism destination is defined as a country, state, region, city or town which is marketed or markets itself as a place for tourists to visit (Holloway, 2006). It is an area or resort with facilities and services that meet the tourist needs such as attraction, amenities and accessibility (Enemuo & Oduntan, 2012). Unlike the definition of a tourism destination, the definition of a host community has been hotly contested in literature. This is partly because of the subjective nature of the word “host”. The “host” is defined by Reisinger and (Turner,2003).as a national of the visited country who is employed in the tourism industry and provides tourist services such as hotelier, front office employee, waiter, shop assistant, custom official, tour guide, tour manager, taxi and bus driver. While the definition is spot-on, it is, however, problematic and misleading as it does not include the unintentional host such as residents or community members (Medleck, 2003). who may not be working in the tourism industry? (Mason,2003). also felt that using a host is somewhat misleading as not all community members welcome tourists and, in some cases, the host community can be an attraction. Such critiques have promoted terms such as “locals”. Further, the word “community” also complicate the phrase as it may include many things which include dance, music, temples, craft and festivals (Mason, 2003). Despite the problems, (Cook, Yale & Marqua ,2006). defined a host community as a town, city or people who live in the vicinity of the tourist attraction and are either directly or indirectly involved with, and affected by the tourist activities which is often visited by tourist.

Destination branding

There is general agreement among academics that branding involves the creation of a name, term, symbol, design or combination of them for an established brand to develop a differentiated position in the minds of the stakeholder and competitors (Badal et al., 2008; Buncle, 2009). The process can involve “fine-tuning” of the brand visual and verbal components which can stimulate new markets, reach new target groups and increase competitiveness (Buncle 2009; Baker 2012; Chellan, Mtshali & Khan, 2013). Therefore, one can say that destination branding is a strategy for managing perceptions about a destination. Branding differentiates the destination from others by giving it an image of its own as well as adding value to the destination (Vanolo, 2008). For example, Rotterdam and Glasgow are not only destinations but are branded as cultural destinations, Paris branded as a destination of romance and New York is branded as the main financial centre in the world.

The prominence of destination branding

There is no doubt that if properly implemented, destination branding can benefit tourism destinations. This is validated by (Anholt, 2003) who states that selling products with well-known names, rather than bulk commodities or generic goods, has long been a smart business to be in. (Guzman,2012). puts forward that a brand is a crucial intangible value creator while (Henderson,2007). denotes that it is an effective visual stimulus that introduces a more persuasive and efficient way to communicate with customers enhancing the visibility and awareness of the destination in the external market. (Ozarslan, 2014). supports this by saying that brands provide an advantage to consumers including risk reductions, increase convenience and establishing emotional benefits. (Ndlovu, 2009) attributes that destination branding creates a deterrent to competitors wanting to introduce similar messages, products and experiences, that is, the ‘first-mover’ advantage while (Pike, 2008) points out that destination branding affords opportunities for disassociating a locality from past failure or other problems. Destination branding creates a unifying focus for all public, private and non-profit sector organisations that rely on the image of the place and its attractiveness as it creates synergies between brands of multi-organisation (Ndlovu, 2009). Considering these factors, branding thus enable the destination to stand out from the crowd and set itself apart from competitors (Therkelsen, 2007). In addition, (Wager & Peters,2009). explain that while a competitor can copy a product, a brand is unique, and whilst a product can easily be outdated, a successful brand is timeless. Destination branding strategy reinforces a positive image already held in the target market (Gudlaugsson & Magnussen, 2012). Though the benefits of branding cannot be disputed based on the above-said reason, one question which still needs to be answered is that “what is the value of the host community in this treasure process?” To answer this question, the next section attempts to outline the muscle of the host community in the branding process as per literature.

Muscle of host community in branding destination

Literature reveals that host communities are increasingly included in regional marketing and place branding (Klijn, Eshuis & Braun, 2012: Sartori, Mattironi & Corigliano, 2012). This is partly because the marketing of tourism destinations has taken a revolution from a “top-bottom approach” to a “bottom-top approach”. The development of this process has been precipitated by the role the host communities play in the process of branding. Different scholars have identified indispensable roles which the host communities play in the establishment of brands. According to (Braun, et al., 2013) residents in this case host community have four different roles in destination branding. First, they play a role in communication, be it sending information or receiving. (Braun, et al., 2013) note that they are the audience receiving messages of destination marketing campaigns and part of the communicated destination brand. This implies that the host community as residents are communication instruments and ambassador networks (Andersson & Ekman, 2009) who disseminate place information. (Braun et al., 2013) branded the host communities as “tertiary communicators” who enhance branding through the word of mouth (WOM). In respect of this, Andersson and (Ekman, 2009) are of the view that consumers have far more confidence in the view of friends and acquaintances than in a message that emanates from advertising or corporate spokespeople. Their “hidden voice” makes them the co-creators and implementers of the brand. As a result of this, engagement of local people leads to successful destination branding (Eshuis, Klijn & Braun, 2014; Rehmet & Dannie, 2013). In respect of the above-outlined arguments the host community play a pivotal role in the brand establishment.

Secondly, host communities are envisioned to be hospitable destination ambassadors who live in the destination (Aronczyk, 2008). hence reinforcing the tourism brand. Host communities are brand ambassadors (Anderson & Ekman, 2009). Local people being the host community create stable situations hence should be noted in branding tourism destinations. (Freire,2009). notes before moving to a place, individuals create an image of a destination by stereotyping the typical local people. He goes on to say the less commercial, aggressive and pushy, and the more relaxed and kind local people are, the more will the brand loyalty increase and trigger positive word-of-mouth. (Anholt, 2005) argues that people have to change their minds about the place. If the people and organisations in a place start to change the things they make and do, or the way they behave – that is the only manner in which a nation can start to exercise some degree of control over its image. This bottom-up approach to destination branding is very important for its success. (Ryan & Silvanto, 2010) say that many brands struggle to succeed when they overlook the perspective of the host population, in favour of expected assessments of tourism development. (Ozarslan, 2014). adds that branding strategies should not only be developed by marketing teams but rather through the cooperation of human resources with marketing. This explains how influential local people are in the branding process. Thus they, according to (Braun et al., 2013). provide legitimisation to any meaning attributed to destination to the public.

Thirdly, the involvement of people in various planning practise is key in attempting to build the brand as it encourages them to become actively involved in changing the conditions that affect the quality of life (Malek & Costa, 2014). Destination marketing tends to construct holistic destination images through umbrella branding often calling upon a supposedly homogenous regional identity among residents of a destination (Jeuring, 2016). This has led to (Ozarslan, 2014). arguing that branding strategies should not only be developed by marketing teams but rather through the cooperation of people with the marketing team. The notion of branding sees internal stakeholders (people) as the “first customer” of the brand and stresses the importance of encouraging them to internalise and deliver the corporate brand values (Sartori et al., 2012). This is supported by Kepferer who claims that “before knowing how we are perceived, we must know who we are” (Kepferer, 1999; Konecnik & Go 2008: Wagner & Peters 2009).

Fourthly, according to (Anholt, 2005). (Katzenbach, 2003). branding should start with residents to attract visitors, as people are the ones who help deliver the experience. The rich culture of people possesses a huge competitive advantage and can be used in the branding process. Strong traditions and a lively culture such as music, dancing and the hospitality of inhabitants contribute to unique moments. Many brands struggle to succeed when they overlook the insights of the host population in favour of an “expert” assessment of tourism development. (Katzenbach, 2003). adds that branding must often start with the people of that destination so that they provide a positive association for visitors with the destination. This is substantiated by Anon in (Bennett & Savani, 2003). when he says “if you don’t have the residents onboard, you will never change an area’s image. The local people need something they can be identified with, even if the world around them – I mean their world – is collapsing”. West (1997:12) hence concludes that place branding is only worthwhile if the values of the brand are “…rooted in the aspirations of the people”. Citizens and residents play a pivotal role in defining how others see the place. This will eliminate the belief from people to see a brand as a DMO baby in which they do not have a significant part to play in its implementation. (Braun, Kavaratzis & Zenger, 2013). believe that participation and consultation with people in the branding process make the brand more effective and sustainable.

Furthermore, the host community allows users to connect, thereby building the brand by facilitating and deepening connections between the brand admirers (Fournier, Solomon & Englis, 2008). A brand with a meaningful portfolio indicating operations of a community will be stronger than a brand without established community connections (Fournier, Solomon & Englis, 2008). Host communities resided by citizens create a concept of citizenship. This brings a notion of belonging and the rights within a destination (Bianchi & Stephenson, 2014). This creates strong relations with people’s identity with the place they reside (Misener & Mason, 2006). As such, the host community can play the role of being responsible for making the brand effectively implemented.

Apart from identified roles the host community play in branding, it should also be noted that not only do they play pivotal role in information but as internal customers (Choo, 2011) since they can also enjoy their local destination (Canavan, 2013). (Soria & Cot,2013). (Jeuring,2017). asserts that residents’ engagement in tourist activities in their region of residence enhances regional identification and tourism may become an inclusive part of citizenship behaviour which enhances the brand. Local people who have more brand-based identification with the destination are likely to participate more in tourist activities. Involvement of the host community, therefore, create an atmosphere of responsibility towards the destination thus improving the image and hospitability. Thus, the inclusion of the host community creates destination identity, dependence, attachment and bonding.

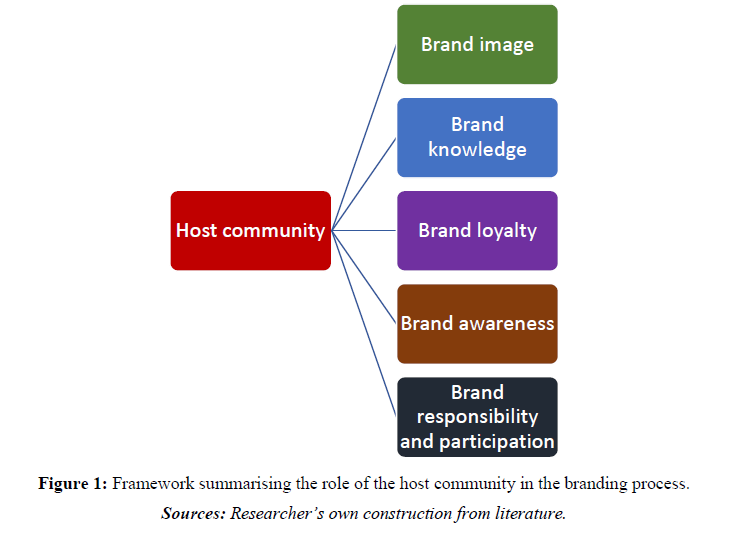

Based on the above-mentioned values, a model can be designed with brand image, awareness, knowledge, responsibility and participation, and loyalty created by the influence of the host community. The below proposed summative framework which shows how people influence destination branding and will be explained in the section which follows (Figure 1).

Based on the literature reviewed above, it is clear that people are indispensable when branding tourism destinations and the destination branding model can be premeditated showing how people influence the branding of a destination since people influence image, brand knowledge, brand loyalty and brand awareness.

Brand image: (Freire, 2007) notes that before moving to a place, individuals form themselves an image of a destination by stereotyping the typical local people. Satisfied residents with positive perceptions of their city reinforce and may communicate favourable associations of that place. Unhappy and dissatisfied residents can harm the brand image of a destination held by visitors and potentially other residents through negative word-of-mouth (Insch & Florek, 2008). This is clear evidence that the host community play a vital role in destination branding.

Brand knowledge: Branding should start with residents to attract visitors as people are the ones who help deliver the experience and have knowledge of the local norms. As a result, the host community are the ones who has brand knowledge and are likely to influence destination branding. People know their culture and values hence are the one who can educate others more precisely. While they practice it, they make it more known to others.

Brand loyalty: Brand loyalty is a measure of the attachment that a customer has to a brand (Aaker 1991, cited in EURIB 2009b). (Hurombo et al., 2014) argue that local people have an impact on the overall destination image affecting brand loyalty and word of mouth promotion. The scholars do agree that friendly people result in a more relaxed environment that allows greater ratification thus encouraging positive word of mouth promoting increased brand loyalty. This signifies the importance of people in a destination as a stakeholder.

Brand Awareness: Brand awareness is defined as a brand’s ability to be remembered and recognized that comes from the mental process used by the customer in identifying it (Keller, 2003). It is reflected by the customer’s ability to identify the brand under a different condition (Hurombo et al., 2014). While Aaker,1991 defines it as the potential of the customer in recognizing or remembering that the brand is present for a certain type of offering. People play an important role in shaping the perception of a place to those who view it thereby promoting destination awareness.

Brand responsibility and participation: Host community have the responsibility of participating in the brand implementation. People not only create positive brands but disseminate the positive brand to a broad spectrum. This hence shows why people are vital in branding a destination.

CONCLUSION

Branding is a useful tool for destination marketing. Given the vital role of branding in the tourism industry, it is prudent for a destination marketing organisation to create effective brands to position themselves in the market. However, for destinations to create effective brands in the branding process they should have a holistic approach including all stakeholders. The host community is one of the most important stakeholders in the branding process. The host community augment the branding process in an area to enhance the brand image, brand knowledge, brand loyalty, brand awareness and brand responsibility and participation. It is therefore a key consideration to comprehend all the numerous roles of the host community to ensure that an effective brand is created in particular in the tourism industry where the product is intangible. It must primarily consider to include the host community in the branding process for the host community possess a lot of benefits in the branding process.

- Andersson, M. & Ekman, P. (2009). Ambassador network and place branding. Journal of Place Management and development 2(1), 41-51.

- Anholt, S. (2005). Brand new justice how branding places and products can help the developing world. Oxford UK Elsevier Butter worth Heinemann.

- Anholt, S. (2003). Elastic Brands. Brand Strategy 28-29.

- Aronczyk, M. (2008). Living the brand nationality globality and identity strategies on nation branding consultants. International Journal of Communication 2(1), 41-65.

- Ashworth, G.J. & Kavaratzis, M. (2015). Rethinking the roles of culture in place branding. Available online at: https://doi.ordg/10.1007/78-3-319-1242-7-9.

- Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G. & Ashworth, G.J., (2015). Rethinking place branding comprehensive brand development for cities and regions. Cham, Switzerland Springer International.

- Badal, J., Bahl, P. & Salbhlok, P. (2008). Learning branding from the experience of Available online at http://www.iitk.ac.in/infocell/convention/papers/ marketing.

- Baker, B. (2012). Destination branding for small cities the essentials for success place branding. Portland Oregon.

- Bennett, R. & Savani, S. (2003). The rebranding of city places: an international comparative investigation. International Public Review 4(3).

- Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M. & Zenger, S. (2013). My city my brand the different roles of resident in place branding’. Journal of Place and Development 6(1),18-28.

- Buncle, T. (2009). Handbook on tourism destination branding: an introductory. World Tourism Organisation.

- Burns, N. & Grove, S.K. (2009).The practise of nursing research appraisal synthesis and generation of evidence. Philadelphia Saunders.

- Canavan, B. (2013). The extent of domestic tourism in Small Island the case of Isle of Man. Journal of Travel Research, 52(3)340-352.

- Chellan, N., Mtshali, M. & Khan, S. (2013). Rebranding of the Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park in South Africa: reflections on benefits and challenges for the former of St Lucia. Journal of Human Economics 43(1), 17-28.

- Cook, R.A., Yale, L.J. & Marqua, J.J. (2006). Tourism the business of travel New Jerseys Prentice Hall.

- Diaz Soria, I., & Llurdes Coit, J. (2013). Thoughts about proximity tourism as a strategy for local development. Cuademos de turisme 32, 65-88.

- Eghbali, N., Kharazmi, O.A., & Rahnama, M.R. (2015). Assessing Effective Factors for the Formation of City Image in Mashhad from the viewpoint of Tourists by Structural Equation Modeling. Science Journal 36(3), 133-148.

- Eshuis, J., Klijn, E.H. & Braun, E. (2014). Place marketing and citizen participation branding as strategy to address emotional and dimension of policy making. International Review of Administrative Science 80(1), 151-171.

- Enemuo, O.B. & Oduntan, O.C. (2012). Social impact of tourism development on host communities of Osun Oshogbo sacred grove. Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2(6), 30-35.

- Fournier, S., Solomon, M.R., & Englis B.G. (2008). In when brand resonate (Schmitt, B. H and Rogers D.I) Handbook on brand and experience management.

- Freire, J.R. (2009). Local people a critical dimension for place brand. Journal of Brand Management 16(7), 420-438.

- Gudlaugsson, T. & Magnussen, G. (2012). North Atlantic Island tourism destination in tourists’ minds. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 6(2), 114-123.

- Guzman, F & Sierra, V. (2012). Public private collaboration branded public service. European journal of Marketing 46(7/8), 994-1012.

- Henderson, J.C. (2007). Uniquely Singapore A case study in destination branding. Journal of Vacation Marketing 13(3), 261-274.

- Holloway, C. (2006). The business of travel England Prentice Hall.

- Hospers, G. (2010). Making sense of place: from cold to warm city marketing. Journal of Place Management and Development 3(3), 182-193.

- Hurombo, B., Kaseke, N. & Muzondo, N. (2014). Critical issues in rebranding evidence from Zimbabwes national tourism organisation. Business Review 2(2), 61-76.

- Hurombo, B. (2012). Critical issues in rebranding Zimbabwe a stakeholder perspective. Master’s Thesis University of Zimbabwe unpublished.

- Insch, A. & Florek, M. (2008). A great place to live, work and play conceptualisation of place satisfaction in the case of a citys residents’ Journal of Place Management and Development 1(2), 138-149.

- Jesca, C., Kumbirai, M. & Hurombo, B. (2014). Destination rebranding paradigm in Zimbabwe a stakeholder approach. Journals of Advanced Research in Management and Social Science 3(1), 1-12.

- Katzenbach. J. (2003). Pride a strategic asset. Strategy and Leadership 31(5), 34-8.

- Kasapi, I. & Cela, A. (2017). Destination branding A review of the city branding literature. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 8(4), 129-142.

- Kavaratzis, M. (2009). Cities and their brands lessons from corporate branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 5(1), 26-37.

- Keller, K.L. (2008). Strategic brand management building measuring and managing brand equity. New Jersey Prentice Hall.

- Kepferer, J.N. (1997). Strategic brand management creating and sustaining brand equity long term. London Kegan page.

- King, C. (2010). One size doesnt fit all Tourism and hospitality’s response to internal brand management. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 22(4), 517-534.

- Klijn, E.H., Eshuis, J & Braun, E. 2012. The influence of stakeholder’s involvement on the effectiveness of place branding. Public Management Review 14(4), 499-519.

- Jeuring, T.H.G. (2016). Discursive contradictions in regional tourism marketing strategies: The case Fryslan, the Netherlands. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 5(2), 65-75.

- Malek, A. & Costa, C. (2014). Integrating communities into tourism through social innovation. Tourism Planning and Development 12(3), 1-19.

- Mazur, B. (2010). Cultural diversity in organisational theory and perspective. Journal of Intercultural Management 2(2), 5-15.

- Misener, L. &Mason, D.S. (2006). Development citizens through sporting events balancing community involvement and tourism development Current Issues in Tourism, 9(4), 384-398.

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Pride, R. (2004). Brand portfolio strategy creating relevance differentiation energy leverage and clarity. New York Free Press.

- Munjoma, K. (2012). Poetic & politics of destination branding rebranding Zimbabwe An evaluative and comprehensive study Master’s thesis. University of Stavanger.

- Ndlovu, J. (2009). The destination branding process and competitive positioning. Pretoria University of Pretoria.

- Ndlovu, J. (2009). Branding as a state strategic tool to reposition a destination a survey of key tourism stakeholders in Zimbabwe Dissertation University of Pretoria.

- Nworah, U. (2006). Re branding Nigeria. Critical perspectives on Heart of Africa image project.

- O Reilly, A., Williams, K.Y. & Barsade, W. (1998). Group demographic and innovation does diversity hep Gruenfeld, D. Research on managing groups and team, 1,183-207, St Louis MO Elsevier.

- Ozarslan, L. (2014). Branding Boutique hotels management and employees’ perspectives. Thesis. Kent State University College and Graduate school of education.

- Piggott, R. (2001). New Zealand and the Lord of Rings leveraging public and media relation in country as brand product and beyond.

- Rijamampinina, T & Carmichael, A. (2005). Pragmatic and holistic approach to managing diversity problem and perspectives in management. 1.

- Ryann, J. & Silvanto, S. (2010). World Heritage sites the purposes and politics destination branding. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 27(5), 553-545.

- Saraniemi, S. & Kylanen, M. (2011). Problematizing the concept of tourism destination: an analysis of different theoretical approaches. Journal of Travel Research 50(2), 133-143.

- Sartori, A., Mattironi, C. & Corigliono, M. A. (2012). Tourism destination brand equity and internal stakeholders an imperial research. Journal of Vocation Marketing 18(4), 327-340.

- Smith, S. l. (2001). Measuring the economic impact of visitors to sport tournament and special events. Annals of Tourism Research 28(3), 829-31.

- Stojanovic, M., Petkovic, N. & Mitkovic, P. (2012). Culture and creativity as driving forces for urban regeneration in Serbia. World Academy of Science Engineering and Technology. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 6(7), 1853-1859.

- Therkelsen, A. (2007). Branding af turisme destination er muligher or problemer. In Sorense, A. Gurundbogi turisme. Frydenlund.

- Vanolo, A. (2008). The image of the creative city: some reflections on urban branding in Turin. Cities, 25, 370-382.

- Wager, O., &Peter, M. (2009). Can association methods reveal the effects of internal branding on tourism destinations stakeholders. Journal of Place Management and Development 2(1), 52-69.

- Anholt, S. (2016). Place identity image reputation. Palgrave McMillan.