Research Article

ITALIAN PUBLIC TOURISM SECTOR, MANAGERIAL APPROACH IN TWO MACRO AREAS: CAMPANIA AND TUSCANY

3618

Views & Citations2618

Likes & Shares

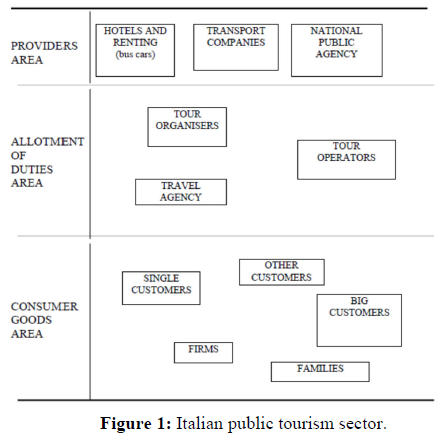

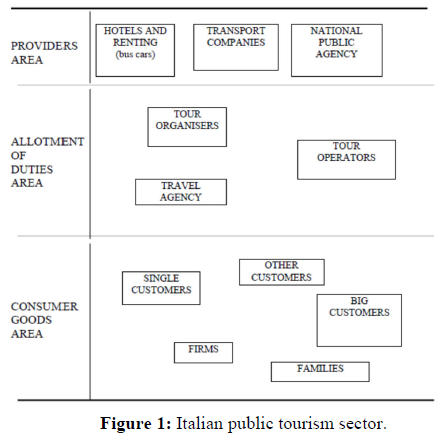

This work takes into account of organizational analysis about the relationship between two different areas, Campania and Tuscany, ofItalian public tourism sector (IPTS). After the presentation of theIPTSwe consider two macro areas, the regions of the Campania and Tuscany, representative of the south and north Italy, analyzing the case study.The sector is summarized in Figure 1, provider’s area, allotment of duties area, consumer goods area. The main data of the sector, the maps of region and SWOT analysis of the two regions will be showed. Data’s analysis underlines strategic role of management in the sector.Furthermore items of questionnaire Likert statements, using factor analysis and varimax rotation,underline different typology of management. We analyze how the Italian managers characterize the structures of the organizational and service provision in Campania (South Italy) and Tuscany (North Italy). In the conclusions the authorsshowsome possible actions to create efficiency and productivityof the areas considered and also to provide a clear picture of the complex tourism system on a macro level.

Keywords: Italian public tourism sector, Managerial approach, Campania and Tuscany, Factor analysis, SWOT analysis, Organization theory

INTRODUCTION

Tourism Sector can be a driving force for local development for all the areas that highlightspotential resources. An expanding sector, it allows to dynamise traditional economic activities and to enhance local cultural specificities, offering people new opportunities for employment (Benur, & Bramwell, 2015). Through a rigorous assessment that takes into accounttrends can make it possible to determine whether a territory has a real tourist development potential that justifies new investments. Numerous studies (Canavan, 2016) have shown that a timely analysis may be supportive of overcoming obstacles such as poor vision of local tourist potentialthat can lead to overly large projects, withadverse environmental impacts: pollution, degradation of natural sites, cultural problems, loss of or folklore of local identity and economic repercussion for all territory dependence, increased cost of living, indebtedness of municipalities. Furthermore an erroneous perception of the characteristics and specifics of the territory makes it more difficult to develop an original local tourist offer that allows differentiation from competing comparable regions (Andraza, Gonçalves, & Norte, 2015). An Insufficient knowledge of customer characteristics and market trends by local managershampers the development of tourist products that can satisfy existing demand. Although it can not provide absolute certainty about the actual development prospects of the sector, a precise assessment of the tourism potential, including managers, constitutes an excellent decision-making basis for to develop sector, enabling to reduce to the slightest risk of engaging in the wrong investment.The study takes into account two Italian regions, Campania and Tuscany, considering tourist morphology and comparative analysis of their public sectors also to provide a clearer view of the local tourist opportunities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Italian public tourism sector

The national figures, concerning the operative sites available to the tourists of the public sector combined, can be synthesized as follows:

- 607 Museums;

- 802 Monuments;

- 330 Archaeological Sites.

More than 70% of the total is owned and managed by the public sector. If the number of tourists is considered by place typology(Italian Tourist Council 2016), art cities are second only to the seaside resorts:

- 38% seaside;

- 30% Cities of artistic and historical interest;

- 15% mountain resorts;

- 8% lake resorts

- 4% hill and various resorts.

Annually, the three most visited public sector attractions are:

- The Colosseum, the Palatine Hill, and the Roman Forum;

- Excavations of Pompeii (Campania);

- Uffizi Gallery, (Florence, Tuscany).

In this context, we analyze the two regions where there are the largest number of tourist visits: Campania and Tuscany.

Case study context

In Europe, it is a cliché to state that the demand for tourism services has increased significantly over the last few decades. Many public organizations (Etzioni, 1964) have recognized (Chemin, 2016) a potential for adding to tourism supply in areas that were previously not considered attractive destinations (Aaker, Kumar, & Day, 2003; Hristov, Minocha, &Ramkissoon, 2018) for tourists. At the local level, (Beirman, 2003) particularly in Southern Europe, tourism has often been seen as a means of generating economic prosperity (Gartner, 2000) and playing a role previously attributed to manufacturing. Additionally, tourism can enable public authorities to achieve a variety of social objectives, such as improving employment (Commission of the European Communities, 2016) and the physical environment of an area (Michailidou, Moussiopoulos, & Vlachokostas, 2016). Campania and Tuscanymanager experiences are within this track, infactthese two regions are driving for development of new investments by the European Union and public actors that are changing the old manufacturing areas in the new and competitive tourist arena (Estol, & Font, 2016). In this context (Aram, 2013) the different two areas of the IPTS will beinvestigated. The Italian public tourism sectoris illustrative of the different, disjointed interests between administrative (Simon, 1947) - organizational and managerial aspects. First, the sectors may be considered as comprising of three areas as shown in Figure 1.

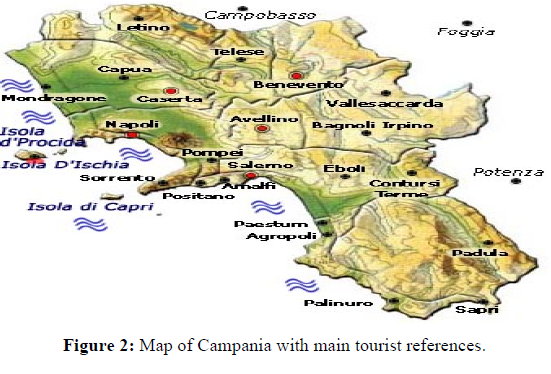

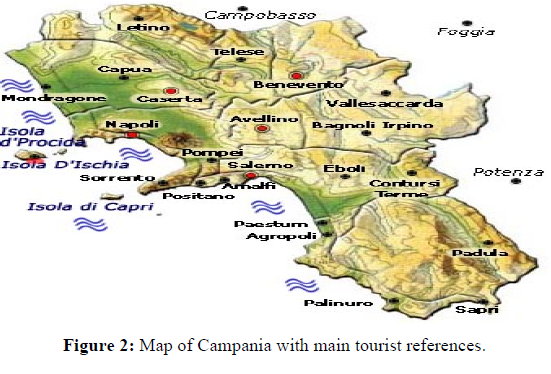

Thus it must interact with the surrounding economic and social environment for which it should fulfill a role of regulating the social (Merton, 1949) and economic processes. The tourist sector is not the result of a simple addition of the performance of all units. On the contrary it depends on a relationship existing among all tourist sector units and of the managers decisions linked to it, among the different economic and social goals and between these and the organizational and managerial actions (Thompson, 1967) of visible hand. To start from this assumption means surrendering the omni comprehensive idea of a tourist sector and replacing it with one of networks of complementary but often competing units (Perrow, 1969). For example, Campania (Figure 2) has a very favorable climate and a wealth of natural resources. The morphology favors the coastal area where most of the plains are situated. The coast presents four gulfs including the gulf of Naples, which provides an excellent view of the only active volcano in continental Europe even though secondary volcanic phenomena like hot springs are still present in certain Neapolitan areas like the Phlegrean Fields. The islands, Ischia, Procida and Capri are quite near and easily accessible, via boat or hydrofoil from different parts of the coast but mainly the port of Naples.

There are many UNESCO sites throughout the region including the recent addition of Naples’s historical city center.

Thus it must interact with the surrounding economic and social environment for which it should fulfill a role of regulating the social (Merton, 1949) and economic processes. The tourist sector is not the result of a simple addition of the performance of all units. On the contrary it depends on a relationship existing among all tourist sector units and of the managers decisions linked to it, among the different economic and social goals and between these and the organizational and managerial actions (Thompson, 1967) of visible hand. To start from this assumption means surrendering the omni comprehensive idea of a tourist sector and replacing it with one of networks of complementary but often competing units (Perrow, 1969). For example, Campania (Figure 2) has a very favorable climate and a wealth of natural resources. The morphology favors the coastal area where most of the plains are situated. The coast presents four gulfs including the gulf of Naples, which provides an excellent view of the only active volcano in continental Europe even though secondary volcanic phenomena like hot springs are still present in certain Neapolitan areas like the Phlegrean Fields. The islands, Ischia, Procida and Capri are quite near and easily accessible, via boat or hydrofoil from different parts of the coast but mainly the port of Naples.

There are many UNESCO sites throughout the region including the recent addition of Naples’s historical city center.

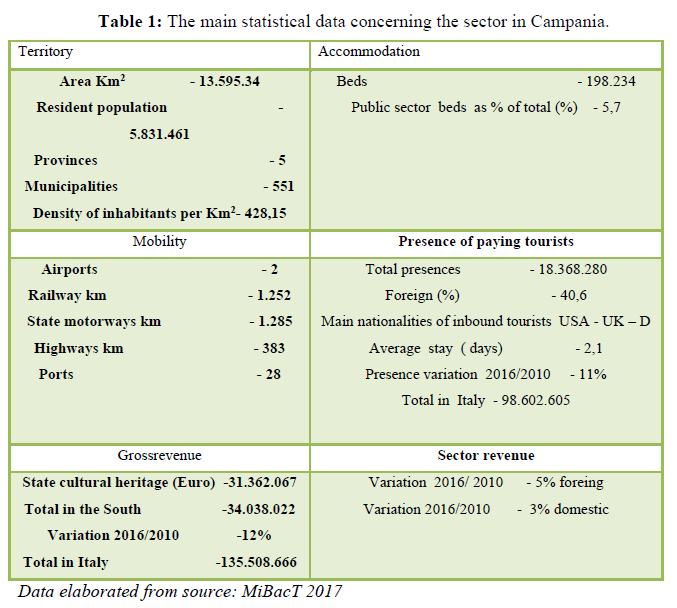

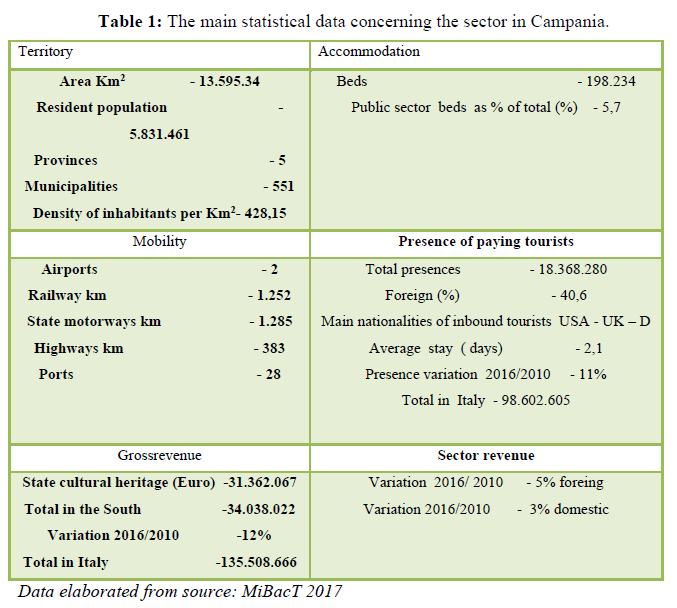

The Campania public tourism sector, particularly, the main statistical data concerning the sector in Campania was represented in Table 1, particularly attention is addressed to negative score about:

- Presence variation – 11%;

- Variation in Gross revenue, -12%;

- Variation sector revenue, -5% foreign &3% domestic.

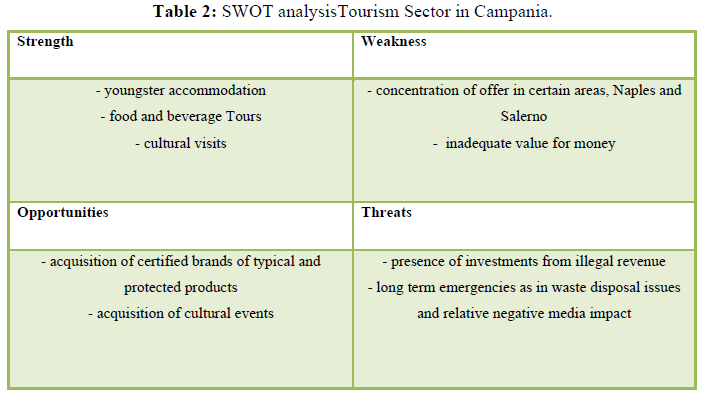

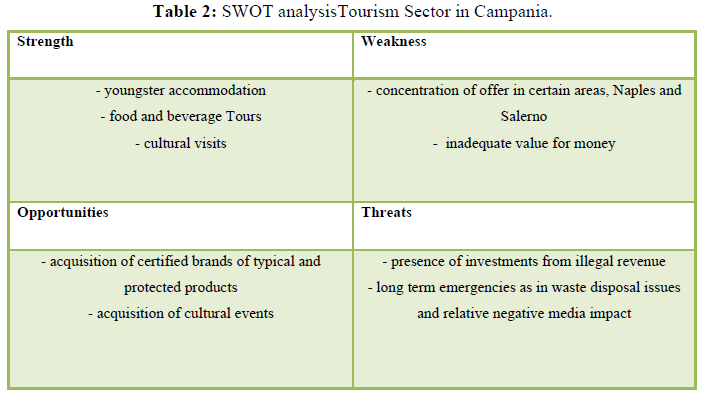

SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats) analysis below synthesizes the sector in Table 2.Is strategic underline structural problems linked to threats, particularly:

- Presence of investments from illegal revenue;

- Long term emergencies as in waste disposal issues and relative negative media impact.

About these problems regional and national action was been implemented but results are disjoint and not effectiveness.

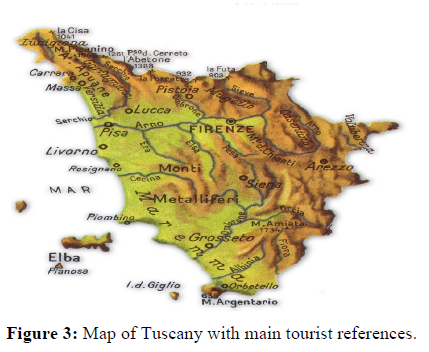

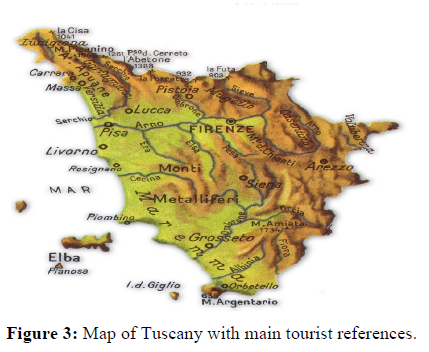

Tuscany (Figure 3) has a very favorable climate and a wealth of natural resources. The morphology favors the coastal area where most of the plains are situated. Tuscany has a triangular shape with a west coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. There are mountain ranges that surround and cross the region and some fertile plains. Florence, Pisa and Empoliare among the most important Tuscan cities and are situated on the banks of the Arno River. In the inland areas there is a tourism related to agriculture linked to the typical wine and food products. The islands, Elba, Giglio, are quite near and easily accessible, via boat or hydrofoil from different parts of the coast but mainly the port of Piombino. There are many UNESCO sites throughout the region.

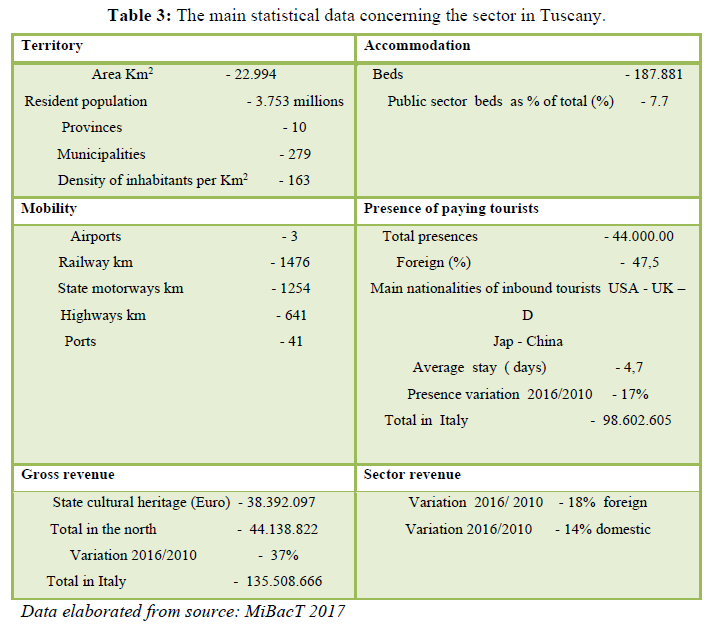

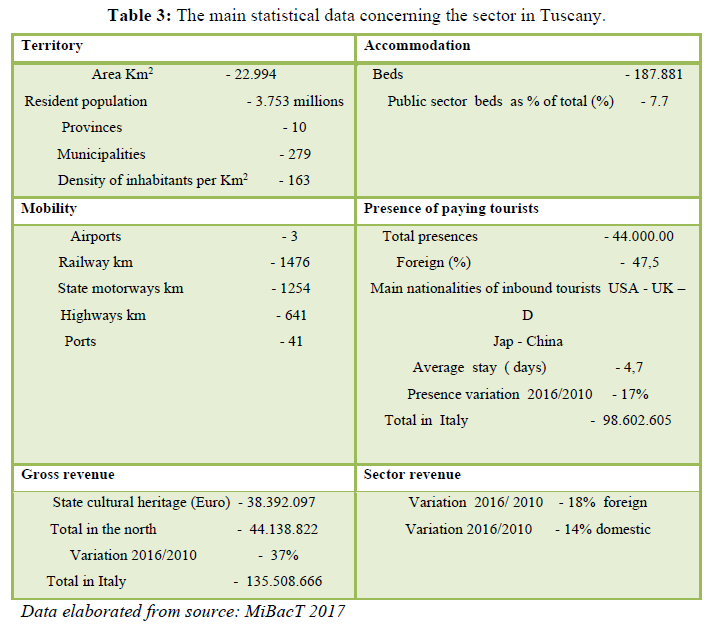

The Tuscany public tourism sector, particularly, the main statistical data concerning the sector in Tuscany was represented in Table 3, particularly attention is addressed to positive score about:

- Presence variation - +17%;

- Variation Gross revenue - + 37%;

- Variation Sector revenue - foreign + 18%,domestic + 14%.

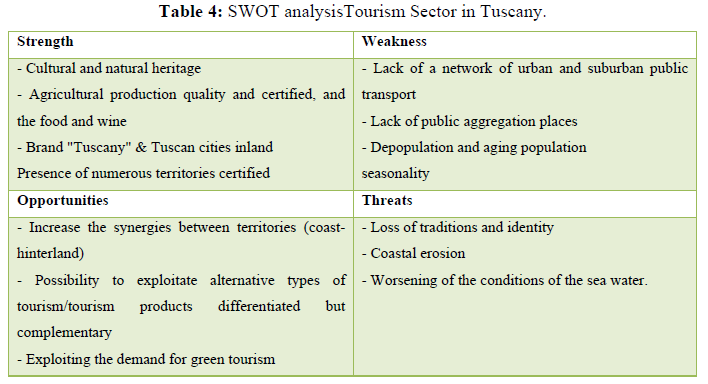

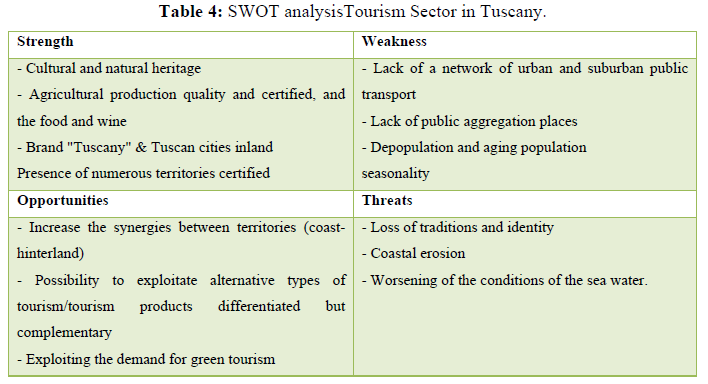

SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats) analysis below synthesizes the sector in Table 4. Is strategic underline structural problems linked to threats, particularly:

- Coastal erosion;

- Worsening of the conditions of the sea water.

About these problems regional and national action was been implemented but results are disjoint and not effectiveness.

These two macro areas considered, Campania and Tuscanyregions, are representative of the tourist Italian public sector with more of 62 thousand of presences on 98 thousand.

Northern vs SouthernItalian public tourism sector

A changing relationship between the northern and southern Italian public sectors (Ouerfelli, 2010) is necessary. These changes affect the attractiveness of destinations, the consequences of tourism development on social and physical environments (Chen, & Var, 2010).

New logic and a cultural challenge are linked to application of management theory in the tourist sector (Chen, 2016). Many issues, including:

- The characteristics of the task the public tourist sector are supposed to carry out;

- The normative foundation of their work and;

- In this context some strategic organizational and managerial elements are considered for to improve management and managers.

These three elements are referred to as the task context, the normative context, organizational context.

The task context

The tourist experience is typically produced by two production circuits. The first relates to travel patterns and motivations. The second is more diffuse and complicated. It concerns the local manager’s goal for which the specific services can be seen as a means and an end. In this latter approach tourism is not about an individual’s concerns, but about the reproduction and development of their country’s culture. In this way the public tourist sector carries out both aggregative and integrative functions. On the one hand they must take as a point of departure citizens’ needs (aggregation); on the other hand they socialize and regulate citizen behavior (integration).

The normative context

The normative context contains the consideration, principles and demands to which the managers must generally relate. In this way we find many varying elements, all of which can be seen as restrictions on internal processes and the way in which services are produced and distributed. The issues here relate to resource use, the productivity and efficiency of services and quality of those services.

The organizational context

In this context some strategic organizational and managerial elements, particularly starting from SWOT analysis and 24privileged witnesses to the tourism sector, 8 for each of the 3 areas that make up the sector in Figure 1 are considered (Blau, 1971). Motivational Factors and working organization (Lundberg, Gudmundson, &Andersson, 2009), knowing how and why to motivate employees is an important managerial skill, motivation is the set of forces that cause people to choose certain behaviors from among the many alternatives open to them.The role of the public institution (William, 2003), public tourist organizations take on the qualities and characteristics of aninstitution. They must become vehicle for societal ambition, combining reliable performance with high levels of legitimacy. Linked to this approach tourist public legislation is strategic (Devine, 2011)for formulate a legal and regulatory framework for the sustainable development and management of tourism.Job stability(Namasivayam, & Zhao, 2007), particularly, the fact of an employee, or a group of employees, being able to keep the same job for a long time. Furthermore investment in information technology (ICT), (Marino, & Pariso, 2017; Baum, 2007) the role of private organization (Wang, & Xu,2014), allotment of duties (Wang, & Wal, 2007),managerial culture (Park, Doh, & Kim, 2014), part of the organization culture, is a major form of manifestation of thehuman factor at the organization level. During their existence, organizations are seen in different ways dueto the powerful influence of the top managers’ professional style and personalities on the people formingthe organization (Dhar,2015).These variables will be investigated for to know better mutual conditioning and possible innovationof the managers (Chen, 2017).

METHODOLOGY

The sample of Italian public managers was selected during June 2017, the interviews has started during October 2016. The high number of Campania and Tuscany managers, 800 for each region, have take many time for organized the contact and the visit in the different organizations (large, small and medium firms). A large part of interviews 70% has been made inside the organization and the remaining part by skype interview. It can be said the IPTS is characterized by:

- A presence of a few large companies (provider area);

- A presence of small firms (Cyert, & March, 1963) (allotment of duties area) with at most

ten employees and,

- A presence of a consumer good area.

The three areas (see Figure 1) has been investigated by questionnaire that take into account, starting from privileged witnesses, three different contest of analysis:

- Social background variables of managers;

- Productivity variables;

- Efficiency variables.

The questionnaire comprised 30 pre-developed, 15 for each part, Likert statements, designed to measure the fivedifferent areas of questionnaire. Specifically, respondents were asked to indicate the level of criticizes on a seven point scale, ranging “stronglycriticizes” (7) to low criticizes (1) by different items.The 30 Likert statements were explored by principal components factor analysis and varimax rotation, which resulted in a four - factor solution, two for each region. The purpose of factor analysis (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995) was to combine the statements into a set factors that were deemed to represent a first organizational types linked to the interviews of managers into different regions. The internal consistency of each factor was examined by Cronbach’s alpha tests. All the alpha coefficients were above 0.5, which means that high correlation existed between the items.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

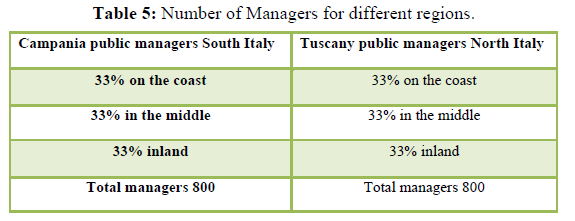

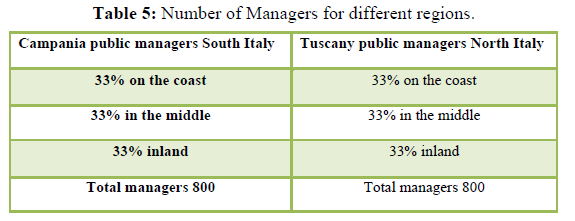

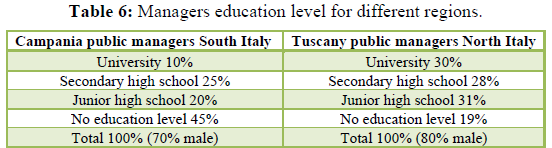

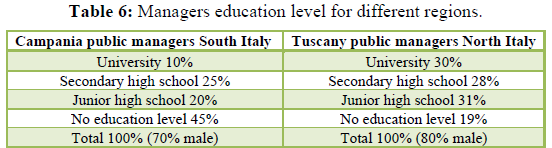

These issues were examined by questioning a sample of Campania and Tuscany managers in the IPTS. These were distributed by geographical and educational attainment as shown in Table 5, 6. Table 6 shows the general lack of tertiary sector educational qualifications among the staff.

The decision to divide the region into three main areas is dictated by the different orientation of the management culture (Schein, 1985) linked to privileged witnesses. Within the three macro areas, culture and service (Selznick, 1953, Sasser, Olsen, & Wychoff, 1978) orientation is homogeneous in relation to the school curriculum and previous experience in the field. Table 6, shows the different number of graduates for the two regions and in particular, the high number of “No educational level” in Campania, is the frequency with the greatest number of responses for both regions. Tuscany with a degree in management, law, engineering, cultural heritage (also these prevail for Campania)andSecondary high schoolcollects with 58%, the highest frequency.

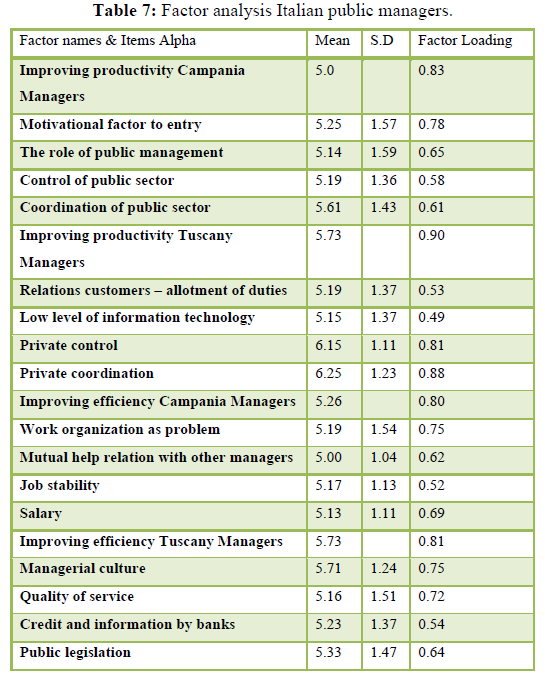

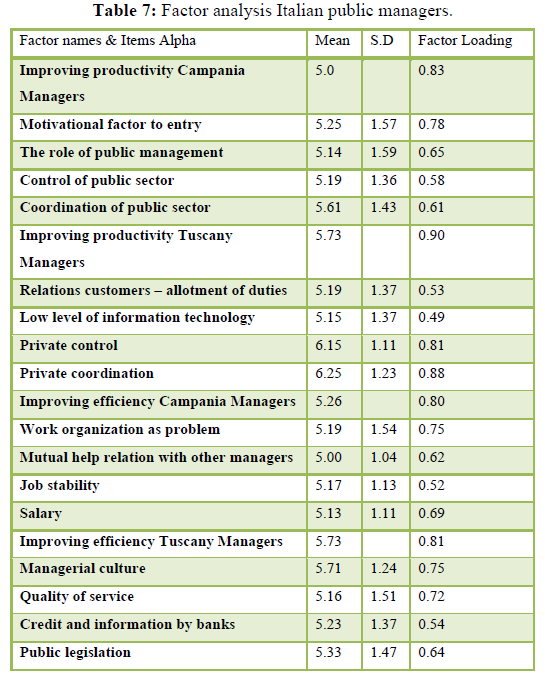

The purpose of factor analysis, which resulted in a three factors solution, was to combine the statements into a set factors that were deemed to represent the organizational types linked to the interviews of managers into different areas. Specifically, items with higher loadings, 16 factors, (Table 7) were considered (alpha coefficients above 0.5) as more important and as having a greater influence (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995) on organizational types.

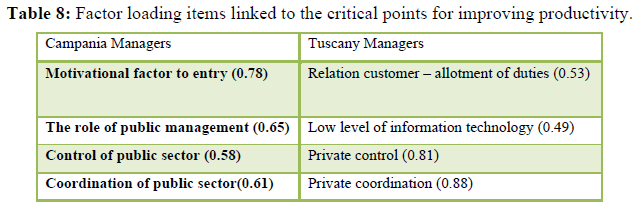

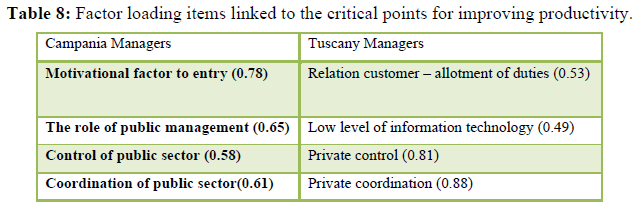

Managers were asked about what they saw as the critical points for improving productivity. The results are categorized in Table 8. South Italian managers (Campania) emphasized motivational factors to entry, especially incentives for productivity and training, and then factors described as ‘the form of management’ and ‘coordination of the tourist sector’. North Italian public managers (Tuscany) considered the first element to be ‘coordination’ and ‘control of public sector’. Both groups of managers underline the necessity of a new normative context and strongly criticize the role of an Italian Government.

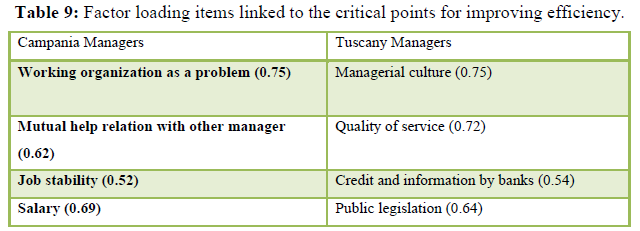

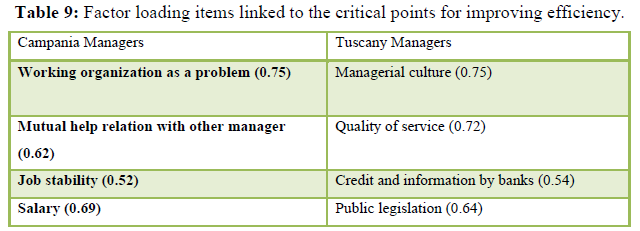

For the items linked to efficiency (Table 9) the critical factors are, for the south managers, Campania: ‘work organization’, ‘mutual help relationships with other agencies’ and ‘salary’. In the first element managers underline the absence of gerarchical influences and ‘professionality’ linked to the service supply. The second element is the necessity to change, for the better, the mutual help relationships with other managers. In this case the managers underline the modalities by which the different members of organization undertake their specific tasks, professional functions and roles. These modalities particularly concern the relations of exchange and their characteristics, linked again to the absence of gerarchical influence. Salary is the last element; the managers argue that individual economic reward should be taken into account to improve productivity and efficiency. North managers, Tuscany, underline the importance of ‘managerial culture’ and ‘quality of service’ in terms of paying more attention to the specific managerial culture of the sector and the needs of its users. One important bottle neck of this second aspect, (quality of service) is linked to the relations between customers and the allocation of duties withreference to the need for a quick response about the coordination and control of information flows.

Starting from Tables 8 & 9, the data showed four different organizational types:

- Insensitive organization;

- Sensitive organization;

- Participated organization;

- Proactive organization.

The insensitive organization, the main characteristics refer to low attention to the identification of user's needs, and to productivity and efficiency. This configuration is present in a large part of Campania, particularly inland and middle. These types of organization takes into account for improving productivity:

- motivational factors to entry (0.78);

- the role of public management (0.65),

- and for improving efficiency:

- Work organization as problem (0.75);

- Salary (0.69).

The sensitive organization, it shows interest in the knowledge of user's needs, and productivity and efficiency. This configuration is present in Campania on the coast and inland of Tuscany. In these areas organization, takes into account for improving productivity:

- control of public sector (0.58);

- coordination of public sector (0.61);

- for improving efficiency:

- mutual help relation with other manager (0.62);

- -job stability (0.52).

Participated organization on themiddle Tuscany, these types of organization takes into account for improving productivity:

- relations customers - allotment of duties (0.53);

- low level of information technology (0.49);

- for improving efficiency:

- public legislation (0.64);

- Credit and information by bank (0.54).

The proactive organization; an organization that shows great interest in user's requests, and productivity and efficiency. This configuration is present in a large part of coast Tuscany.

These types of organization takes into account for improving productivity:

- private control (0.81);

- private coordination (0.88);

- for improving efficiency:

- managerial culture (0.75);

- Quality of service (0.72).

DISCUSSION

The four organizational typologies,the insensitive, sensitive,participated and proactive organization, highlight in the empirical results how themanagers have strategic influence on the services productivity of tourist sector linked to natural, archeological and cultural heritage resources of the country.In the areas considered in the analysis, Campania and Tuscany, south and north Italy, emerge two different approaches linked to managers within IPTS.In recent years there has been an increasing interest in the use of management theory (Italian Tourism Council, 2016) within the IPTS. This interest has two aspects: first, an interest in the application of management theory in the tourist sector. This takes the form of importing ideas and methods developed in and for the private sector. The assumption is that the private sector is superior to the public sector in specific ways: private sector organizations are more costconsciousness, more inclined to implement modern personnel management and more capable of developing corporate culture as a steering instrument. Such a debate considers facets like incentives for productivity and particularly the necessity to create in the tourist sector some reliable measures of management efficiency. The second aspect is an interest in the use of management theory in the study of the tourist sector. Here the aim is somewhat different.Because the management theory should be verified starting from the real behaviors and organizational culture of managersdo theories and concepts from management theory help us to understand the tourist sector better.From 2013 the public sector in Italy has become more important than previously, with particular attention to the role of managers. About this in the literature review- case study context - and empirical results the managers of two different areas have two approaches completely different: in Tuscany are important variables linked to private control and coordination and underline the importance of ICT and allotment of duties. Campania instead, always improving productivity, underline the importance of control and coordination of public sector, motivational factor and the roleof public management.The improving efficiency in two regions underline a different variables set that for Tuscany is linked to: managerial culture, quality of service, role of bank and public legislation, Campania instead: working organization, mutual help, job stability and salary. The difference between the regions within same Country, highlights that despite the profound differences in managerial approach between the two regions, both attract a growing number of tourists and are within the nation at the forefront of the importance the tourism industry provides to GDP (see SWOT analysis literature review). Operative and theoretical action are important for to improve tourist sector. At operative level some organizational action are strategic for manager in different regions. Particularly a cross contamination between managers in the different areas of regions could be an interesting operative approach for improve efficiency and productivity of Campania by large part of coast Tuscany managers is important underline that operative action should be linked to theoretical level will be important implemented a governance idea of Italian public tourism sector. In addition there are different configurations in the same areas, such a view rejects a stance whereby the normative and task context can be regarded as ultimate and unchanging. It must instead be seen as under constant development and re-interpretation.

CONCLUSION

We argues that these two regions linked to the strategic role of management are important for economic development of Italian country. This work argues that while change is possible, such change must take into account to the different experiences and culture of managersofthe two areas of Italy and in each of these broad areas there are significant differences in relation to the location and culture offer the tourist service with different market opportunities of each. Of over-riding importance is a needed change in terms of values and operative decisions.We have drawnfourorganizational typologies, insensitive; sensitive; participated; proactive organization. The first concerning insensitive organization, representative of large part of Campania, particularly inland and middle. Here the manager underline the importance of motivational factor to entry and work organization as problem, in this configuration the high number of “no educational level”, is a problem for to improve efficiency and productivity. Second configuration, underline the importance of mutual help relation with other manager. Here the need is for a managerial approach between different stories, cultures and tourism management, a tight confrontation to understand what the best strategies to follow and implement are. It is worth noting that in these two configurations the presence of Campania is exhausted and therefore it is placed between the insensate and sensitive configuration, while here have the inland of Tuscany linked to no educational level.In the third configuration there is only Tuscany, in particular the center, with the need for greater investment in ICT, low level of information technology, was considered an interesting variables for to improve the productivity. The proactive organization is present in large part of coast in Tuscany, where are concentrate managers with degree in management, engineering and law and there is a family firm structure with excellent control and coordination of activities. Managerial culture and quality of service are best practice.Is necessary a managerial cross contamination between the manager of two different regions where the proactive organization managers with a job and cultural focus training support particularly insensitive organization with relevant presence in Campania: inland and middle. Managerial cross contamination is an important level for change. The national policy linked to tourist sector, as governance idea by managerial approach, starting from different culture of managers is a strategic action parallel to the first one. These to levels, operative and theoretical, can represent an interesting mix of organizational and economical levels for improve Italian managers of IPTS.The values and culture of publicservice in order to produce a tangible economic and social return, is underline in the north, Tuscany. South Italy Campania, to replace one bureaucracy by another is not progress. The role of Italian public tourism sector is an open question and therefore, in the diagnosis of reform, actually there isnot a one bestway.Managerial approach and manager role are a strategic variable for to improve public sector and its performance. A kind of diagnosis that reflects the nature of different systems and contributes to the discovery of strategic key areas in which a change could produce a better performance for the service and users.

- Aaker, D.A., Kumar, V. & Day, G.S. (2003). Marketing Research. 8th Edition, Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Andraza J.M., Gonçalves, H.S., &Norte, N.M. (2015). Effects of tourism on regional asymmetries: Empirical evidence for Portugal. Tourism Management 50, 257-267.

- Baum, T. (2007). Human resources in tourism: Still waiting for change. Tourism Management 50(6), 1383-1399.

- Beirman, D. (2003). Restoring tourism destinations in crisis. A strategic marketing approach.CABI Publishing. pp: 288.

- Benur, A.M., & Bramwell B. (2015). Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tourism Management 50, 213-224.

- Blau, P.M., & Schoenherr, R.A. (1971). The Structure of the Organizations, Basic Books.

- Canavan, B.J. (2016). Tourism culture: Nexus, characteristics, context and sustainability. Tourism Management 53, 229-243.

- Chen, B.T. (2017). Service innovation performance in the hospitality industry: The role of organizational training, personal-job fit and work schedule flexibility. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 26(5), 474-488.

- Chen, X. (2016). Tourism enterprise: Developments, management and sustainability. Tourism Management 55, 324-325.

- Commission of the European Communities. (2015). The tourism sector of the community: a study of concentration, competition and competitiveness. pp: 182.

- Chemin, J.E. (2016). Re-inventing Europe: the case of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela as European heritage and the political and economic discourses of cultural unity.International Journal of Tourism Anthropology 5(1-2), 24-46.

- Chen, P.T., & Var, T. (2010). Distribution of tourism economic impacts: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Tourism Policy 3(2), 91-112.

- Cyert, R.M., & March J.G. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice-Hall International series in management.

- Crozier, M. (1963).The bureaucratic phenomenon. Available online at: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199646135.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199646135-e-26

- Devine A., & Devine, F. (2011). Planning and developing tourism within a public sector quagmire: Lessons from and for small countries. Tourism Management 32(6), 1253-1261.

- Dhar, R.L. (2015). Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tourism Management 46, 419-430.

- Dwyer, L., &Wickens, E. (2013). Event Tourism and Cultural Tourism: Issues and Debates. Routledge, pp: 280.

- Eisenschitz, A. (2013). The politicization and contradictions of neo-liberal tourism. International Journal of Tourism Policy5(1), 97-112.

- Estol, J.,&Font, X. (2016).European tourism policy: Its evolution and structure. Tourism Management52, 230-241.

- Etzioni, A. (1964). Modern Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall.

- Gartner, W.C. (2000). Tourism Development and Growth-the challenge of sustainability. Routledge, pp: 179-198.

- Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. & Black W.C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Open Journal of Applied Sciences 7(4).

- Hristov, D., Minocha, S., &Ramkissoon, H. (2018). Transformation of destination leadership networks. Tourism Management Perspectives 28, 239-250.

- Italian Tourism Council. (2016).Available online at: http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/sito-MiBAC/Contenuti/MibacUnif/Comunicati/visualizza_asset.html_293698082.html

- Lundberg, C., Gudmundson, A., & Andersson, T.D. (2009). Herzberg's Two-Factor Theory of work motivation tested empirically on seasonal workers in hospitality and tourism. Tourism Management 30(6), 890-899.

- Marino, A., & Pariso, P. (2019). Italian Cloud Tourism as Tool to Develop Local Tourist Districts Economic Vitality and Reformulate Public Policies. In International Conference on P2P, Parallel, Grid, Cloud and Internet Computing. pp 609-615.

- Marino, A., & Pariso P. (2017). Economic-Organizational Analysis of the Public Tourism Sector in Campania, Italy: Management andHuman Asset Issues.Journal on Tourism & Sustainability 1(1).

- Merida, A.L., Carmona, M., Congregado, E., &Golpe, A.A. (2016). Exploring the regional distribution of tourism and the extent to which there is convergence. Tourism Management 57, 225-233.

- Merton, R.K. (1949). Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/user1/Downloads/Merton,%20Social%20Theory%20and%20Social%20Structure.pdf

- MiBac. (2015). Available online at: http://www.statistica.beniculturali.it/

- Michailidou, A.V., Moussiopoulos, N., &Vlachokostas, C. (2016).Interactions between climate change and the tourism sector: Multiple-criteria decision analysis to assess mitigation and adaptation options in tourism areas. Tourism Management 55, 1-12.

- Namasivayam, K., Zhao, X. (2007). An investigation of the moderating effects of organizational commitment on the relationships between work–family conflict and job satisfaction among hospitality employees in India. Tourism Management 28(5), 1212-1223.

- Ouerfelli, C. (2010). Analysis of European tourism demand for Tunisia: a new approach. International Journal of Tourism Policy 3(3), 223-236.

- Park, D.B., Doh K.R., & Kim K.H. (2014). Successful managerial behaviour for farm-based tourism: A functional approach. Tourism Management 45, 201-210.

- Perrow, C. (1969). Organizational Analysis: a sociological view. Tavistock Publications, London. pp: 192.

- Sasser, W.E., Olsen, R.P. & Wychoff, D.D. (1978). Management of service operations: texts cases and readings. Boston Mass.

- Schein, E.H. (1985). Organization Culture and Leadership. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Selznick, P. (1953). TVA and the Grass Roots. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp: 274.

- Simon, A.H. (1947). Administrative behavior. Wiley, NY.

- Swanson, J.R. & Brothers, G.L. (2012). Tourism policy agenda setting, interest groups and legislative capture. International Journal of Tourism Policy 4(3), 206-221.

- Thompson, J.D. (1967). Organizations in action.Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory.Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1496215

- Tribe, J. (2016). Strategy for Tourism. Goodfellow Publishers Ltd. Oxford, pp: 280.

- Wang, C., & Xu, H. (2014). The role of local government and the private sector in China's tourism industry. Tourism Management 45, 95-105

- Wang, Y., &Wal, G. (2007).Administrative arrangements and displacement compensation in top-down tourism planning- A case from Hainan Province, China.Tourism Management28(1), 70-82.

- William, K. (2003). Tourism public policy and the strategic management of failure. Routledge, 1st Edition, pp: 312.