Research Article

IS THE PARTICIPATION OF WOMEN IN THE RURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT OF SERBIA VISIBLE?

1094

Views & Citations94

Likes & Shares

The economic position of women is unfavorable, and access to services is important for strengthening economic participation is extremely limited. Compared to rural men, it is higher among rural women participation of inactive and unemployed (55% of women versus 39% of men). Educational programs for acquiring new knowledge and skills, especially those adapted local economic conditions, are generally not available to women. The lives of women and their families marks the predominant gratification of the basic existential need, with highly represented material deprivation; participation in the social community is superficial, cultural patterns consumption indicates passivity and dominance of lifestyles aimed at mere reproduction. The authors presented a short part of the research on the position of women in the rural tourism sector. Interview research in rural areas of Serbia shows a very weak connection of the female workforce with rural tourism, although they can contribute to improving the development of this activity. A brief overview of the work and certain segments of the research will be given in the following paragraphs.

Keywords: Rural Development, Tourism, Women, Employment, Serbia.

INTRODUCTION

Serbia has a large number of villages with natural and cultural values, but unfortunately insufficiently valorized areas and poorly represented on the tourist market. The diversity of tourist resources and the richness of the cultural heritage are enriched by the hospitality and cordiality of the rural population. The issue of rural development and the well-being of the rural population is one of the main issues of the overall sustainable development of Serbia. Rural areas still represent a significant part of the territory of Serbia 85%, and a significant part of the population of Serbia still lives in them 42% (Gajić et al., 2018). However, rural areas face a number of serious problems such as strong depopulation, economic underdevelopment, rising poverty and generally unfavorable living conditions. The development of rural tourism in Serbia dates back to the 1970s (Cvijanović et al., 2020). Serbia is one of the most agrarian and rural countries in Europe. In such a context, women are seen as subjects, not objects of development or non-development, as agents, not as victims, as those who possess valuable human resources for development, and not as those who seek help and who are dependent on "help. Gender property inequalities in the surveyed households are very pronounced - women in the status of helping household members are usually not the owners of the houses in which they live, they do not own land, nor the means of production. Only every tenth household in the sample lives in a house owned by a female member. The authors of the paper conducted a survey on the position of women in the villages of Serbia. The aim was to determine the position of women in the development of rural tourism, and the contribution of women to general rural development. Descriptive statistical analysis determined the sus demographic characteristics of the respondents, while the t - test significantly confirmed that there is no statistically significant difference in the categories of the position of women in relation to education as a category. The importance of the research is reflected in a comprehensive overview of the unenviable position of rural women in Serbia. On this basis, this research, as well as similar ones in the world, can contribute to the creation of strategic measures for the advancement of women, and their activation in the field of tourism and contribution to economic development, as well as gender equality.

However, the position of women in the countryside, from the perspective of gender equality, has been the subject of a small number of studies. Rural areas are in many ways specific to urban areas and as such deserve special attention, which means that gender policies need to be adequately contextualized (Baum, et al., 2016). Although it is generally accepted among development actors that it is impossible to define gender policies without their adequate contextualization, in Serbia there is a deficit of knowledge about who are women in the countryside, how they live and what they think (Gajić, et al., 2018). In a word, they are not sufficiently recognized as subjects, whether they are development policies, research or specific activities. If we talk about them, it usually seems from two perspectives that have their undoubted limitations. The first perspective is one that sees women, and especially rural women, exclusively as “victims” of traditional patriarchy and transition, and the second perspective is one that focuses the entire approach to development on women rather than gender (Minoz, 2005). It is assumed that gender differences and similarities are manifested primarily in the sphere of everyday life, i.e that they structure the everyday life of women and men in a specific way. However, what is characteristic of rural areas on the periphery is not only the increase in poverty, but the process of impoverishment, which is closely linked to the collapse of previous development achievements and the collapse of human, institutional, infrastructural and natural resources (Risman, 2004). Gender regimes are always a specific dynamic of relations between genders, as large social groups, and they are ultimately socially, culturally and historically conditioned. Behind gender differences are quite strong and stable structures (economic, political, cultural) that reproduce, change, redefine or re-construct them (Baum, 2007; Tom, 2015). Assisting household members, according to the definition of official statistics, are persons who are engaged in family work without being paid for that work. While in the EU this category of active persons is in the process of disappearing (0.9% of total employment), according to LFS data from 2007-6.7% of total employment in Serbia goes to assisting household members. The majority of this category are women (74%), and the vast majority of assisting household members (93%) are employed in agriculture (SBS, LFS, Report for 2006) (Gajić, et al., 2020). The authors conducted an on-site interview survey, on a total sample of 99 rural women. The aim was to determine their position, if they participate in rural tourism development. A brief overview of the research is given, with the aim of pointing out the main characteristics of women's participation and unenviable position. SPSS software version 23. oo was used. Descriptive statistical analysis showed basic demographic indicators, participants, while t-test proved that there are no statistically significant differences in relation to the category of education. The position of women remains unenviable and very bad in the villages of Serbia. The significance of this paper is of a scientific and social character, because on the basis of the obtained data it will be possible to analyze the position of women, and to take corrective measures to bring about changes and their greater engagement in the field of rural development.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Numerous studies in Europe show that rural women are willing to stay in their communities and contribute to their development, provided that certain conditions exist, which include: the possibility of employment nearby, including part-time jobs; the possibility of gaining work experience and qualifications; local education and training opportunities; business services that will support women's projects and women's entrepreneurship; developed local public transport; developed network of preschool institutions and services for the elderly and sick (Charlsworth, et al., 2014). The position of women in the countryside is the result of the position of women in society as a whole, the position of agriculture as an economic branch, global economic processes that affect agricultural production, the demographic situation of the rural population, the position of rural areas in relation to urban, ecological situations rural areas, levels of development and acceptance of technological change, as well as relations between majority and minority communities (Elaine, et al., 2017).The European Parliament's report on the situation of women in rural areas in the EU, one of the most recent documents related to public policies aimed at improving the position of women in rural areas (2008), pointed out that gender mainstreaming is a key strategy. not only for the promotion of equality, but also for economic growth and sustainable development (Fu, et al., 2020).

Gender theory as a social structure must clarify certain phenomena in organizations with attention to gender implications (Gentry, 20007). Gender is deeply embedded as a basis for stratification not only in our personalities, our cultural rules or institutions, but in all of these, and in complicated ways. Nowadays, it is very difficult for women in the countryside to achieve and harmonize their work and family functions, because they do not have enough support from institutions (Zheng, et al., 2019). Women engaged in rural tourism, mostly live in the countryside and are engaged in agriculture (Thrane, 2008; Chang, et al., 2018). Women have limited opportunities for employment, education and economic independence, do not own property, and find it very difficult to start their own private business. In some parts of Serbia, there is progress in this regard, in the sense that women from rural areas are recognized in the competitions of relevant institutions. The basic characteristics of rural tourism in Serbia are small and underused accommodation capacities, underdeveloped capacities of medium quality, incomplete basic and supplementary offer, low prices of services that characterize small economy, small investment capacities, inadequate promotion, inadequate labor force (Demirović, et al., 2017; Eslami, et al., 2019).

As for investing in rural tourism, it has practically been reduced to investing in public infrastructure, which is primarily of social importance, and only then important for the development of tourism. Revenues are generated from accommodation, food and beverage services to the greatest extent. Revenues from ancillary services are almost negligible. Rural tourism can usually only be one of the sources of alternative income in the region, so its role in sustainable development is greatly influenced by the performance of other economic sectors. In transition countries, changes have become more frequent, affecting both urban and rural populations, but mostly women (Fleisher, et al., 2000). The participation of women in the process of maximizing human resources in rural areas can affect the revitalization of the local economy, poverty reduction, economic growth and sustainable development. Women in their participation in rural tourism development affirm their activism through various handicrafts (Kara, et al., 2012). Handicraft production is considered the second source of income for farms after primary agriculture, and it can be a promising branch that with minimal investment can provide self-employment and a source of income for over a thousand women from all over Serbia and contribute to tourism and promotion of the country and region (Thrane, 2008). Therefore, women’s participation must not be negligible in tourism and the sustainable development of society and cultural values. Gender research in tourism helps to explain the current situation of the role of women in this sector. The work that women do in rural areas still seems “invisible” and is often underestimated and insufficiently recognized despite the fact that a woman is the main head of the family household. That is why it is necessary to understand, evaluate and affirm women (Yang, et al., 2016). Women participate significantly less in the labor force than men, either as employed or unemployed persons (Gentry, et al., 2007). Their activity and employment rates lag far behind men’s rates, and the absence of a difference in unemployment rates may indicate that in unfavorable labor market conditions, women are more easily discouraged and stop looking for work and become inactive. The position of these women was shown to be equal to that of women in agriculture. One third of women in rural Europe are employed in food production, and almost more than half in the food-related services sector.

METHODOLOGY

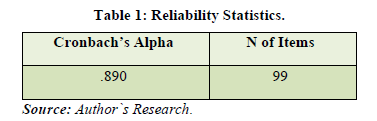

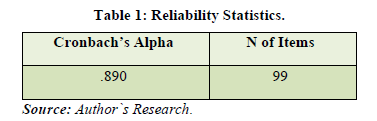

The research was conducted in the villages of Serbia, on a total sample of 99 women from the village, participant in the survey. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the socio-demographic profile of the rural population and to describe the perception of the rural population about the development of tourism, as well as for their support. The reliability of the questionnaire was checked by Cronbach's Alpha (must be above 0.07), as well as the confirmation of the grouping of the given items into four groups through factor analysis. The factor analysis also confirmed reliability, through the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy, whose value had to be greater than 0.6, in order for each item to gain in reliability. The authors also used the t test of significance statistics. T-test for independent samples, also known as Student's t-test, compares the average values of two independent groups of samples, the same dependent variable, continuous type. This test is applied when unknown variance of basic sets, so that it is evaluated on the basis of sample variances.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1. Gives an insight into the reliability test, in this case α is 0.890, which indicates a very high reliability of the questionnaire.

A total of 99 women took part in the survey in Serbia, who were ready to give complete answers to the questions. The largest percentage of survey participants ranged in age from 30 to 50 years (64.4%). Most of our interlocutors have completed high school (67.7%) and most have had work experience. Older women mostly lost their jobs due to the bankruptcy of the company in which they worked or because they could not reconcile business and family obligations. However, younger interviewees worked illegally, most often in trade or trafficking, and did not see opportunities to find employment in the formal sector. The majority of survey participants stated that 64.6% had a desire to improve (m = 1.54; sd = 0.787). Only 17.2% were against training for work in rural tourism. The authors of the paper asked the research participants whether there are real opportunities for training and education, more precisely whether such training workshops are organized. A total of 59.6% of respondents gave a positive answer, and 35.4% negative (m = 1.45; sd = 0.594). There was no training on standards, but there were other trainings on rural tourism. Depending on the municipality, some participants attended trainings. However, the importance of tourism for the village is not a question to which women have given an affirmative answer. Most of them declared themselves indefinitely, more precisely that they are not sure that tourism will contribute to rural development (59.6%). Only11.1% of women are sure that tourism is the future for their village. The participants in the survey think that tourism can influence the independence of women in rural areas. A total of 83.8% gave an affirmative answer and 13.1% a negative answer (m= 1.19; sd = 0.467). Family support for the inclusion of women in rural tourism development is very important. The arithmetic value was m = 1.04, and the standard deviation was sd = 0.224. A total of 97% of women gave an affirmative answer to this question regarding family support. Participants point out that engaging in rural tourism requires the joint work of the whole family. All household members have equally important but different roles. In some households, in addition to their regular jobs, women make art objects, souvenirs and sell them. All women surveyed said that tourism affects their budget. The arithmetic value for this item was m = 1.00. The importance of rural tourism is reflected in the sustainable development and preservation of the traditions and culture of the people. Respondents of mostly the same opinion 65.7% confirmed the fact, and 18.2% denied (m = 1.51; sd = 0.761). Most of the interviewees believe that the development of tourism in their village increases the importance of women’s work in the countryside (76.8%).

Women in the countryside do not have working hours, they are mostly engaged in unpaid, housework, and the care of children (their own or grandchildren) and the elderly is exclusively theirs. In addition, most of them are engaged in agricultural work. Households inhabited by several generations and extended families have a clearer division of roles: everyone is responsible for their work (orchard, greenhouse, livestock, cooking), with household chores being distributed among female family members. The traditional division of roles is maintained in the domain of unpaid work while at the same time taking over men’s jobs. Compared to rural men, the share of inactive and unemployed people is higher among rural women. Among employed women, as many as 58% are employed in agriculture. In addition, employment in agriculture takes place almost entirely within the household. A large number of women have the status of an auxiliary member of the household, more precisely, women extremely rarely participate in the ownership of the household and are not equal in deciding on the production and distribution of income. The same is the case when it comes to the education and training of women in the countryside. Most of them believe that tourism increases the level of their knowledge and awareness of society, 57.6% (m = 1.63; sd = 0.803). A total of 76.8% believe that the development of rural tourism can contribute to the stay of women in the countryside, more precisely to reduce migration to urban areas. The arithmetic value for this item was m = 1.23, and the standard deviation was 0.424. By further conversation and surveying the interviewees, it was concluded that 58.6% believe that tourism will provide them with a better future, while 22.2% deny this fact. In the villages where they come from, patriarchal upbringing is present, which is confirmed by the survey of interlocutors where 67.7% gave an affirmative answer (m = 1.06; sd = 0.703). What the largest percentage of survey participants agree on is that the position of women in the village is very poor (97%).

The authors performed a t - test of statistical significance of the difference between the arithmetic mean of given educational subjects and the poor position of women in rural areas. Based on the obtained data, it is noticed that there is no statistically significant difference of arithmetic means, with: t statistical = 1.212, with statistical significance df = 97, and 95% confidence interval (L = 0.236; U = 0.057). The level of education does not affect the attitude of the interlocutors that the position of women is very bad. The largest percentage of them confirmed that.In 80% of cases, rural women earn less than 50% of household income. However, although a large percentage state that they cannot estimate, the fact is that a large number of women contribute to the family budget through a monetary contribution that is at least 20% higher than that of men. Examining the decision-making process as a key determinant of equality has shown that the most important decisions are most often made together. But if they are not brought together, then the influence of the husband is far greater than the influence of the wife.

Although women are the vital factor on which rural revitalization and rural development in general depend most, their disadvantage and the problems they face, from basic living needs to long-term interests in sustainable development, remain a marginal topic in processes and policies, from entity to local level. Rural women generally play a significant role in the economic survival of their families and communities (Asadzadeh & Mousavi, 2017). However, rural women generally receive little or no recognition for their efforts, and are often denied access to the results of their work or the benefits of the development process. Women in rural areas have a double burden of farming and housework, and in some cases, if employed, formally or informally, even a triple burden. On the other hand, there is a big difference between different households, especially between different generations of women.

In a rural family, the entire burden is on the back of a woman. He has to listen to the older members of the household, and the husband is the head of the family and his word is first and last. They do both men’s and women’s jobs. Women in the countryside do not have time to follow the news and ask for the information they need so they do not even know all their rights.

Nowadays, it is very difficult for women to achieve and reconcile work and family functions, because they do not have sufficient support from institutions. In the countryside, this problem is particularly pronounced. Rural women have limited opportunities for employment, education and economic independence.

CONCLUSION

Rural women around the world, including Serbia, play an important role in the development of rural areas, but are exposed to various forms of discrimination. Women living in the countryside are a very diverse social group, but what they have in common is that they are not sufficiently recognized in society or in the local community, and the jobs they do every day are underestimated and unrecognized. Women living in rural areas are at increased risk of poverty, are less likely to find employment, and health and social care services are inadequate. Farmers-pregnant women and mothers-in-law are in a particularly unfavorable position because they do not exercise the right to financial compensation during maternity leave because they are not recognized in the legal system as employed persons or entrepreneurs. Therefore, they are not subject to regulations relating to the exercise of the right to financial support for families with children, primarily the right to financial compensation during maternity leave and leave from work to care for a child. With modest opportunities for their own and children's education, the existing infrastructure in the villages is worse than in the city. Nowadays, it is very difficult for women to achieve and reconcile work and family functions, because they do not have sufficient support from institutions. In the countryside, this problem is particularly pronounced. Rural women have limited opportunities for employment, education and economic independence. Most often, they do not own property, which is a limiting factor in starting their own business. However, the impression is that this situation is slowly changing, so women from rural areas are recognized in the competitions of relevant institutions. At the same time, associations are being established, manifestations are being organized whose task is to connect, educate and economically empower rural women. The position of women in the countryside is difficult, and prejudices limit their progress, the importance and need for their economic empowerment must be constantly pointed out, on the one hand, and on the other hand motivate them to take care of their health and go for preventive medical examinations. women in the countryside live in a patriarchal and traditional environment, so men are mostly homeowners. Many women in the countryside are not employed, they are registered as housewives and often do not have health and pension insurance. Lately, there has been more and more talk about the position of women in the countryside, but the real truth is that only women who live that life can talk about it. Only we know and feel all the problems and needs. In the research, the authors came to the position of women in rural areas of Serbia, even when it comes to tourism, which is the great future of rural Serbia.

- Asadzadeh, A., & Mousavi, M.S.S. (2017). The Role of Tourism on the Environment and Its Governing Law. Electronic Journal of Biology 13(2), 152-158.

- Baum, T., Kralj, A., Robinson, R.N., & Solnet, D.J. (2016). Tourism workforce research A review taxonomy andagenda. Annals of Tourism Research 60, 1-22.

- Baum, T. (2007). Human resources in tourism Still waiting for change. Tourism Management 28(6), 1383-1399.

- Chang I.K.G., Chien, H., & Hen, H. (2018). The Impacts of Tourism Development in Rural Indigenous Destinations an Investigation of the Local Residents Perception Using Choice Modeling. Sustainability 10, 2-15.

- Charlesworth, S., Welsh, J., Strazdins, L., Baird, M., & Campbell, I. (2014). Measuring poor job quality amongst employees The VicWAL job quality index. Labour& Industry A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 24(2), 103-123.

- Cvijanović, D., & Gajić, T., (2020). Analysis of the Market Values of Lemeska spa Importance and Possibility of Renewal Through the Cluster System. Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development in Terms of the Republic of Serbia Strategic Goals Realization Within the Danube Region. Thematic Proceedings. Institute of Agricultural Economics Belgrade 177-193.

- Demirović, D., Kosić, K., Surd, V., Zunić, L., & Syromiatnikova, Y. (2017). Application of tourism destination competitiveness model on rural destinations. Journal of Geographical Institute, Jovan Cvijić SASA 67(3), 79- 295.

- Elaine., C., Catheryn K., & Charles, A., (2017). A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tourism Management 58, 89-100.

- Eslami, S., Khalifah, Z., Mardani, A., Streimikiene, D., & Han, H. (2019). Community attachment tourism impacts quality of life and residents support for sustainable tourism development. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 36(9),1061-1079.

- Fleischer, A., & Tchetchik, A. (2005). Does rural tourism benefit from agriculture. Tourism Management 26(4), 493-501.

- Fu, X., Riddersataat, J., & Jia, H. (2020). Are all tourism markets equal Linkages between market-based tourism demand quality of life and economic development in Hong Kong. Tourism Management 77, 2020.

- Gajić, T., Penić, M., Vujko, A., & Petrović, M.D., (2018). Development Perspectives of Rural Tourism Policy Comparative Study of Rural Tourism Competitiveness Based on Perceptions of Tourism Workers in Slovenia and Serbia. Eastern European Countryside 24(1), 144-154.

- Gajić, T., Vujko, A., Petrović, M.D., Mrkša, M., & Penić, M. (2018). Examination of regional disparity in the level of tourist offer in rural clusters of Serbia. Economic of agriculture Ekonomikapoljoprivrede 65(3), 911-929.

- Gentry, K.M. (2007). Belizean women and tourism work: opportunity or impediment Annals of Tourism Research 34(2), 477-496.

- Kara, D., Uysal, M., & Magnini, V.P. (2012). Gender differences on JS of the five-star hotel employees the case of the Turkish hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 20(7), 1047-1065.

- Bullon, F.M. (2009). The gap between male and female pays in the Spanish tourism industry. Tourism Management 30(5), 638-649.

- Risman, B., (2004). Gender as a social structure Theory wrestling with activism. Gender and Society 18(4), 429-451.

- Thrane, C. (2008). Earnings differentiation in the tourism industry gender human capital and socio demographic effects. Tourism Management 29(3), 514-524.

- Tom B., (2015). Human resources in tourism: Still waiting for change e A 2015 reprise. Tourism Management 50, 204-212.

- Yang, E.C.L., & Tavakoli, R. (2016). Doing tourism gender research in Asia an analysis of authorship research topic and methodology. In Tourism and Asian genders C. Khoo Lattimore & P. Mura Bristol UK Channel View 22-39.

- Zeng S., Liu W., & He J. (2019). Rural Revitalization How to Develop Rural Tourism Guo Yanron. The renewal of rural tourism model based on Internet Jushe 34, 8.