Research Article

SAFETY MOTIVATION FOR DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL AND TOURISM EXPERIENCE: IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINED PATRONAGE FOR THE TRAVEL AND TOURISM INDUSTRY IN CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA

6321

Views & Citations5321

Likes & Shares

This study was aimed at understanding the perceived relationship between safety motivation and travel/tourism experience, and also, safety motivation for domestic and international travel and tourism patronage in Cross River State, Nigeria. Cluster and purposive sampling techniques were used in sampling 70 key informants who were engaged in key informant interview sessions and focus group discussion sessions. Also, Yaro Yamene formula was used in downsizing the huge study population to 265 sample size for questionnaire distribution. The result shows that these civil servants perceived significant relationship between safety motivation and, travel and tourism experience in Cross River State. The last result also shows that there is above average patronage for domestic and international travels in Cross River State despite the activities of militants in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. The implication of the study is that there is reasonable safety guarantee for travel and tourism experiences in Cross River State Nigeria.

Keywords: Safety motivation, Travel experience, Tourism experience, Sustainable tourism, Pearson correlation model, Post-primary school teachers.

The UNWTO's Annual Report (2016) “affirmed the importance of travel, noting that it' has become one of the fastest growing international tourism segments representing more than 23 percent of tourists traveling internationally every year” (UNWTO, 2016). Travel is one of the essential components of human living not minding the distance travelled or the mode used (Nwankwo, 2017). It is central in tourist activities hence an individual may not be classified as a tourist until some certain criteria is taken into consideration, and travel is one of the essential parts of such criteria (Breda & Costa, 2005; Chang, 2007; Richards, 2015; Han, Kim & Kiatkawsin, 2017).

However, previous studies identified some notable factors that influence travel and tourism experience. This includes safety issues, level of income, tourist attitude, situational factors, attitude of the host, and environmental factors among others (Laws, 1995; Venkatesh, 2006; Nwankwo, 2017). These factors revolve around motivation which initiates the travel intention among tourists or other travelers (Chang, 2007; Correia, Oom do Valle & Moço, 2006).

Hence, travel motives and motivations are among the most revered factors in travel decisions (George, 2005; March & Woodside, 2005), likewise safety motivation which has so many implications for the travel industry since the dawn of the new millennium. Food safety issues, crimes, natural disasters, health hazards and terrorism, communicable diseases, among others, are the predominant safety concerns (Huang & Xiao, 2000; Breda & Costa, 2005; Popescu, 2011; Kim & Chalip, 2004; Nwankwo, 2017).

The incidence of 9/11 in USA had a major setback in the travel industry and the industry has not completely recovered from the effect. This effect had great negative economic implication on the global economy through the sets back of the travel industry which is one of the prominent global industries across continents (Breda & Costa, 2005; Popescu, 2011; Tarlow, 2002; Henderson, 2007; Cohen, 2012). This is coupled with the most recent global economic disaster, Covid-19 pandemic. Some literatures have identified safety as the major concern for the travel and tourism industry. Terrorism, militancy, banditry, crime among others are the trending challenges of the travel and tourism industry across the globe (Sömez & Graefe, 1998a; Sonmez, 1998; George, 2005; Neumayer, 2004) and dangerous communicable diseases like the Ebola, Zika virus, Flu and Convid-19 pandemic, among others.

However, some studies have noted that there is decline in travel and tourism experience among civil servant in Nigeria since the turn of the 21st century as a result of average income level of this category of income earners in Nigeria. These studies may have anchored their arguments on the fact that about 70% of civil servants in Nigeria earn less than ₦2,000,000.00 (less than 5000USD) per annum. Also, that their limited income has been channeled to family needs, children’s educational development, personal carrier development, farming activities (in some cases), among others, with less than 5% of their income channeled to travel and tourism experience (Aribigbola, 2009; Gberevbie, 2010; Aluko, 2012; Salau, 2015; Magbadelo, 2016; Iwuagwu, Onyegiri & Iwuagwu, 2016; Aduwo, Edewor & Ibem, 2016; Eze, 2019; Ogechi; 2019; Nwanunobi & Odum, 2019). In addition, some studies have noted that the level of insecurity in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, occasioned by militant activities, has crippled the travel and tourism statistics in the region. As a result, those states in the region have recorded low patronage from domestic and international travels since the turn of the 21st Century (Paki & Ebienfa, 2011; Olasupo, 2013; Dialoke & Edeja, 2017; Moses & Olaniyi, 2017; Abomaye, Williams, Abomaye, Tamunobarasinpiri & Iyerikabo, 2018). However, these claims motivated this research which seek to understand how civil servants perceive the relationship between safety motivation and, travel and tourism experience, and also understand the implications of safety motivation for domestic and international travel and tourism patronage in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. One of the states in the region (Cross River State) was sampled for the study with focus on post-primary school teachers as civil servants and other tourists/visitors to the state.

METHOD

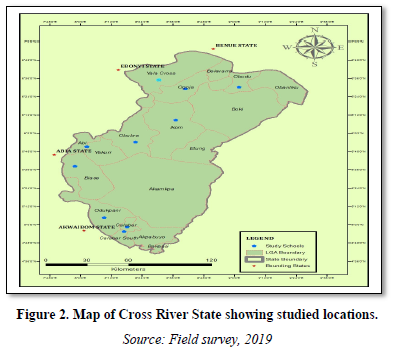

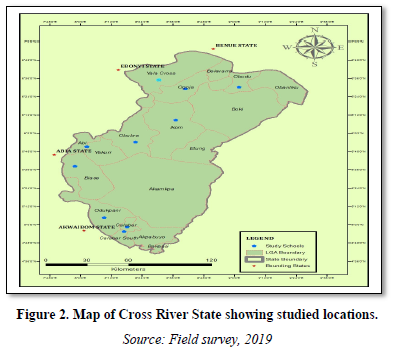

Both qualitative and quantitative research approaches were used for the study. For the qualitative approach, cluster and purposive sampling techniques aided in the clustering of secondary schools in Cross River State into ten clusters, and five key informants were purposively sampled from each of the ten clusters to give a total of 50 key informants. In addition, 20 tourists/visitors were conveniently sampled from notable tourist sites in the state for more in-depth interview sessions. The opinions of these tourists were used to verify the claims of those secondary school teachers that were used for the study. Ten Focus Group Discussion sessions were organized for each of the clusters. The FGD sessions lasted for one hour forty minutes on the average. This was complimented by detailed field observations. However, from the quantitative approach, Yaro Yamene formula was used in downsizing the study population to 265 sample size, and simple random sampling techniques was further used in the questionnaire distribution. However, 265 questionnaires were distributed but only 232 were returned for the analysis. 125 teachers and 107 tourists/visitors made up the returned questionnaires. Pearson Correlation was used in understanding safety motivation for travel and tourism experience among the study population. T-test analytical method was used to test the alternative hypothesis at 0.5 significance level. Mean and standard deviation were used to answer the research questions.

PREVIOUS STUDIES

Some studies have maintained that a greater percentage of civil servants in Nigeria are below average income earner (Aribigbola, 2009; Iwuagwu et al., 2016; Aduwo et al., 2016; Adegun, Joseph & Adebusuyi, 2019). These studies went further to assert that these civil servants spend less on relaxation and travel needs that do not add to their physical income. They put more effort on providing the basic needs on man for their families. Also assert that the inability of these civil servants to engage in travel and travel experience is only the function income factor and not safety. In addition, Aluko (2012), Salau (2015), Eze (2019), Anunobi and Odum (2019) and Ogechi (2019) in their separate studies inform that frequency of travels and visits to tourist sites in Nigeria is quite poor among the civil servants who are greater in population and maintained the bulk of low income earners in Nigeria. These studies maintained that this has adversely affected the aggregate patronage on the transport and travel industry in Nigeria. Most of these studies anchored their arguments on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs which placed safety among the least needs. Although this is not in tandem with the views of Castelli (2018) who maintained that apart from income level, other factors like choice, amount of leisure and safety can determine the frequency of travels among adults. This view of Castelli was among the motivations for this current study to see if safety as a factor do motivate travel and tourism experience among civil servants in Nigeria regardless of the low-income factor.

Another motivation for the second objective of this study came from some results from some other studies on the state of safety and its implications for travel and tourism experience in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. In their separate studies, Paki and Ebienfa (2011), Olasupo (2013), Moses and Olaniyi (2017), Dialoke and Edeja (2017), inform that persistence activities of militants have grossly affected the economy of the region. This has characterized the region with high rate of insecurity among other issues. The threat to human lives and properties has negatively affected the rate of travel and tourism experience in the various states in the region. These studies further claimed that safety issues as a result of militant activities in the region have reduced the tourist/visitors flow to the region (Paki & Ebienfa, 2011; Olasupo, 2013; Moses & Olaniyi, 2017; Dialoke & Edeja, 2017) resultant safety factor on human lives and properties. Also, Abomaye et al. (2018) had in their study maintained that there is decline in domestic and international travel and tourism activities in the Niger Delta as a result of intense militant activities in the region; hence the government has to put in some measures to check these militant activities and save the region from total economic collapse. This is also the motivation for the second objective of this study which tends to investigate the level of domestic and international patronage on travel and tourism in the region.

However, from some other studies, Floyd, Gibson, Pennington-Gray and Thapa (2004) conducted a survey on the “effects of travel motivation on satisfaction using the case of older tourists. The findings of the study highlighted the relationships between four motivations - culture, pleasure-seeking, relaxation and physical and overall tourist satisfaction with the destination. In particular, their results indicate that the effects of the four motivations vary depending on the age of the respondents. Also, Cooper & Hall (2008) conducted a study to understand the travel motivation among youth travelers in Kenya. Their results show that students formed the majority of youth travelers in Kenya, and further demonstrated that “push” factors are more important determinants of youth travel in Kenya than the “pull” factors. In addition, Oh, Fiori and Jeong (2007) carried out a study on travel motivations and experience of tourists to a South African resort. The study revealed that the main travel motivations are resting and relaxation, enriching and learning experiences, participation in recreational activities, personal values and social experiences.

It is imperative to note from this study that motivation is a factor in choice and frequency of travel. The motivation varies from financial motivation, leisure motivation, time motivation and other categories of motivation. However, this current study extended the existing literature on motivation for travel choices, destinations and frequency, by investigating the relationship between safety motivation and travel and tourism experience among civil servants in Nigeria. Their frequency of travel and that of other tourists to the state to understand further the influence of safety motivation on domestic and international patronage on the travel and tourism industry of Cross River State, Nigeria. Moreover, Post-primary school teachers and tourists/visitors in this particular state were targeted for the study. The result of the study is expected to reveal the perceived relationship between safety motivation and travel and tourism experience among civil servants in Cross River State, and also the level of domestic and international patronage on the travel and tourism industry in the state.

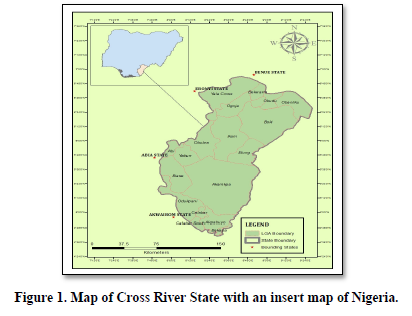

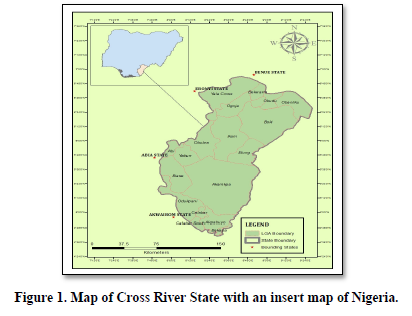

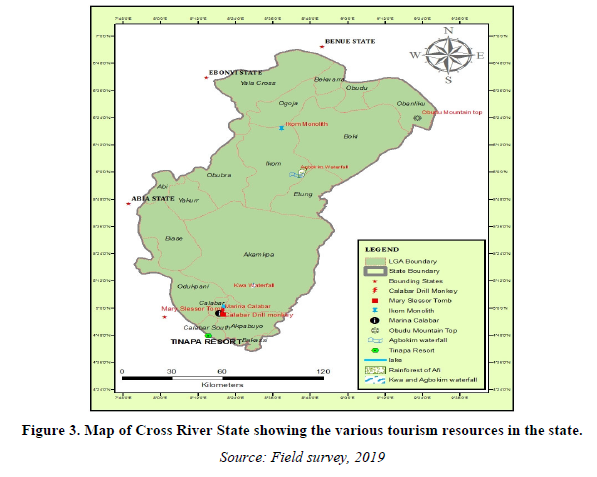

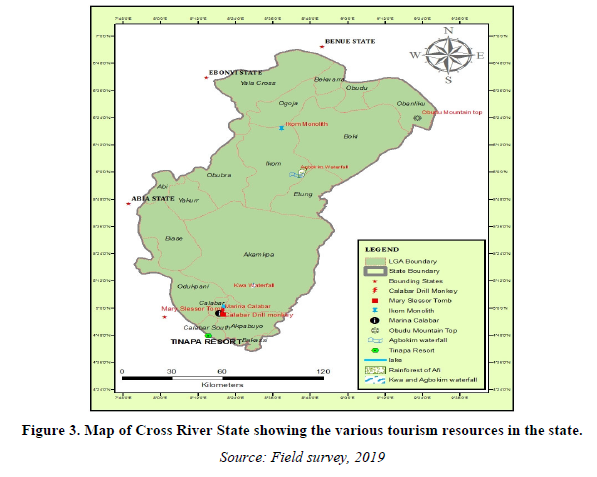

Brief information on the study area

Cross River is among the states in south southern part of Nigeria (Figure 1) Ejagham, Qua and Efik are the major ethnic groups in the state. The state has a major river that lies between latitude 5°45' N & 8°30' N and longitude 8°18' E & 8°22' E. Also the state has landmass of 20,156km2” Major cities in the state include Ugep, Obanliku, Akampka, Obudu, Ikom, Ogoja, Clabar, Akpabuyo, Biase, Obubra, and Odokpani among others.

INVENTORY OF MAJOR TOURISM RESOURCES IN CROSS RIVER STATE

There are some notable tourism resources in Cross River that have the potentialities of attracting huge number of tourists and other visitors. These include the famous Obudu mountain resort located on a plateau found on the Oshie Ridge of the Sankwala Mountain range of Obanliku Local Government Area of the state. The resort which is said to be closer to Cameroon has a temperate climate that fluctuates between 20-24 degrees Celsius on daily basis. It has unique natural, cultural and man-made attractions. Another interesting tourist resources in the state is the Afi Rainforest and Waterfalls in Agbokim Wildlife sanctuary. It is a protected area for wildlife preservation in the state.

There is also Tinapa Business Resort which is a man-made attraction and event center built by the state government in partnership with some private sector establishments. The resort is made up of an open exhibition area where trade exhibitions and events, coupled with a movie production studio, take place.

Moreover, there is a popular museum in Calabar that is known as an Old Residency Museum which was said to have been built in Glasgow Scotland in 1884 and shipped to Calabar Nigeria to house the then colonial governor. It was declared a national monument by National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) in 1959. Apart from the colonial heritage, the museum also has in its collections relics of ancient palm oil trade in the area, slavery, coupled with relics of Efik history. Mary Slessor’s Tomb Duke town within European Cemetery is another notable attraction in the state. The woman contributed significantly in the abolishment of slavery, unlawful killing of albinos and twins in the history of the people.

Other notable attractions in Cross River State include Marina Resort; Slave history museum that gives a historical reconstruction of the slave era in Nigeria; Slave Anchor which is used to commemorate the arrivals and berthing of slave ships from Europe; Ekpo Hall which was an old court that was used by the British Colonia government to judge offenders and punished them accordingly; Ekpe Shrine (Egbo)- one of the remarkable masquerade festivals in the state with historic shrine in Duke town; Chief Ekpo Bassey House which was declared monument to mark the contribution of a notable lawyer from Cameroon to the historical development of Calabar; European cemetery where notable European figures in the historical development of Calabar were buried; Cross River National Park; among others (Figure 3).

RESULTS

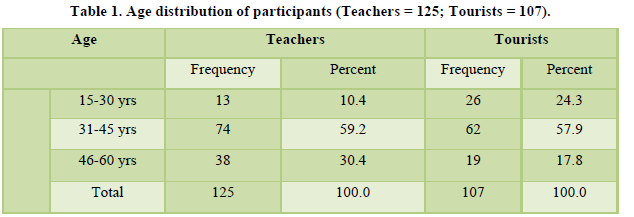

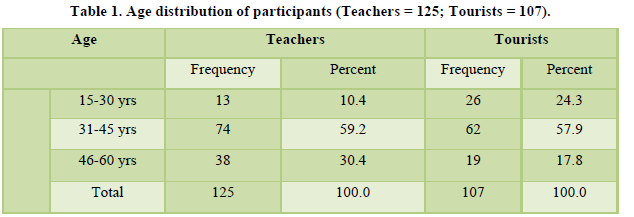

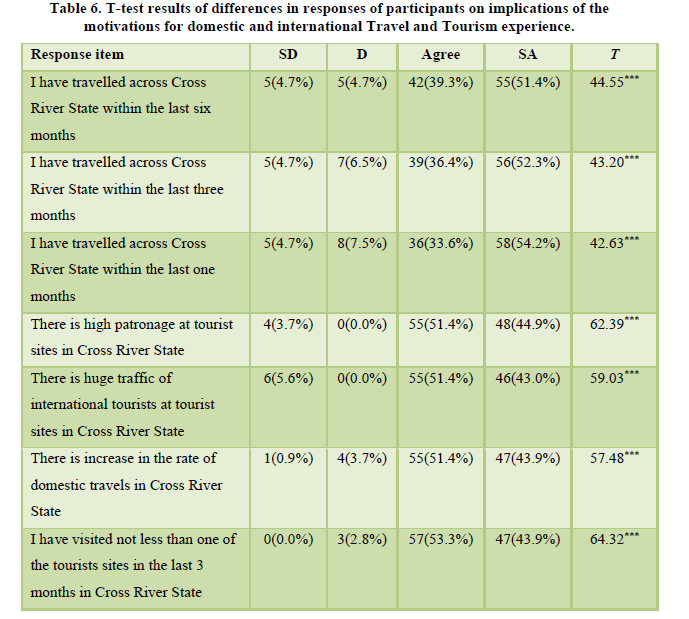

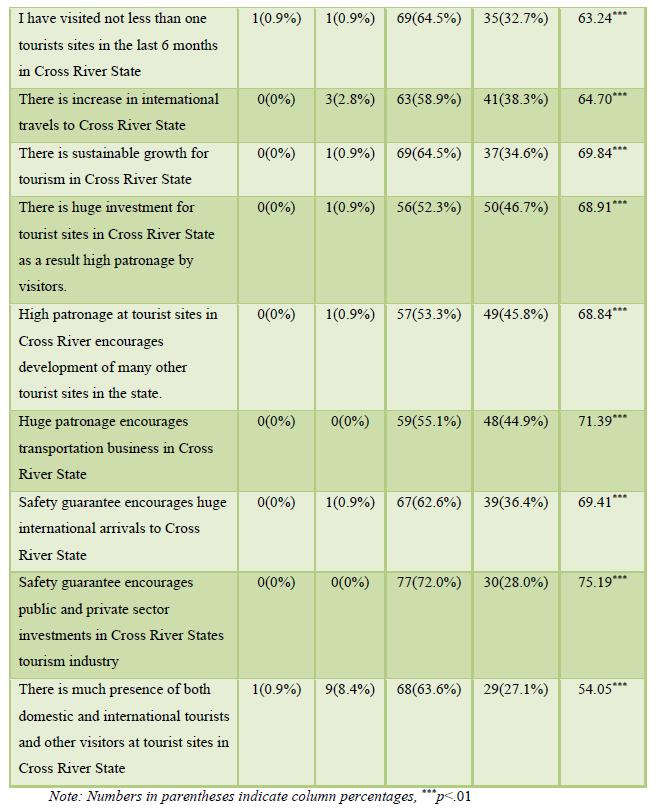

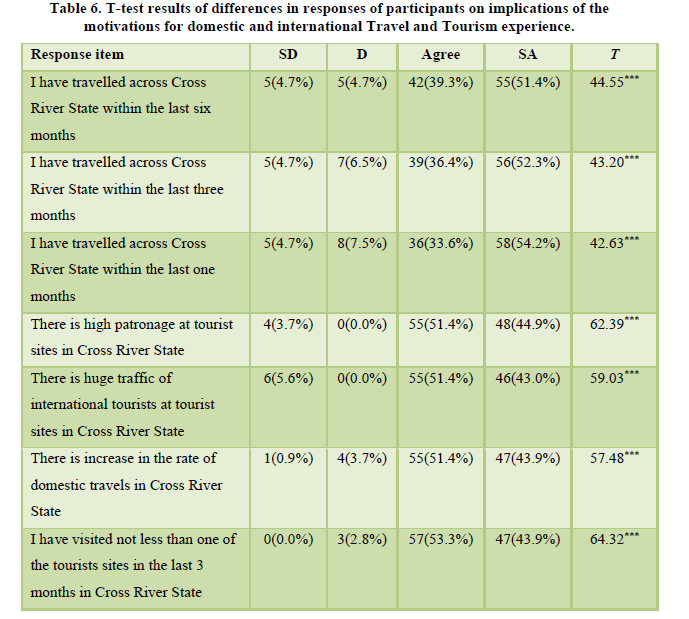

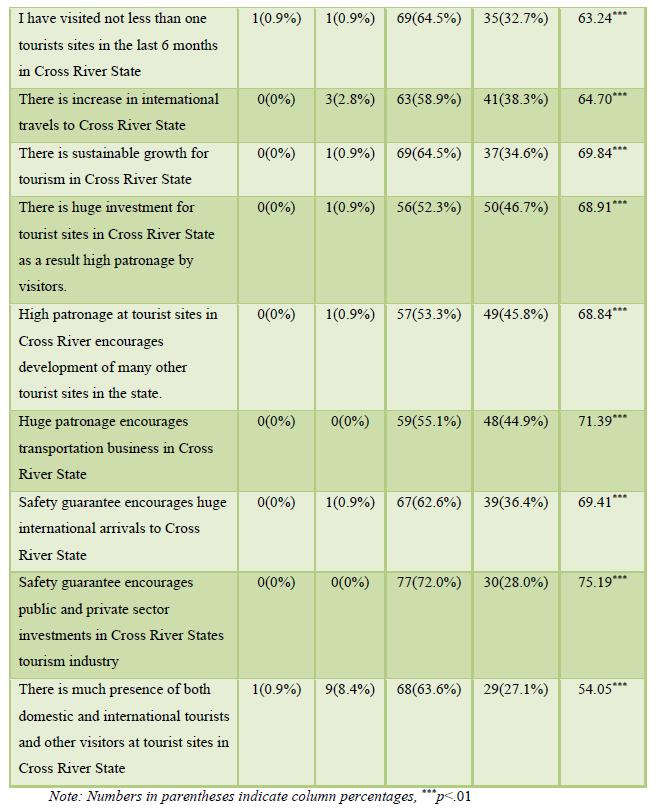

The results are organized based on the study’s hypotheses. Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown first for the teachers indicating associations of safety motivations for travel and tourism experience. The data analysis for tourists showed the implications of the motivations for domestic and international travel and tourism experience.

Table 1 showed that for the teachers, majority of them were aged between 31-45 years (n = 74, 59.2%). Similarly, majority of tourists were also aged between 31-45 years (n = 62, 57.9%), signifying the active age for leisure travel and other travels.

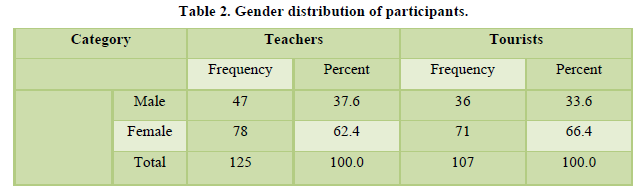

Table 2 showed that majority of the teachers who took part in the study were females (n = 78, 62.4%), and majority of the tourists were females too (n = 71, 66.4%).

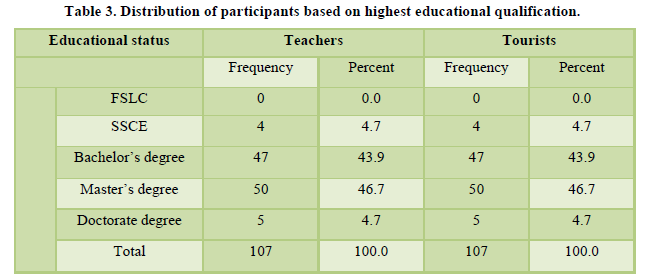

In the samples for the study, many of the respondents (teachers and tourists) had master’s degree (n = 50, 46.7%). This number was followed by the bachelor’s degree holders who were 47 (43.9%). None of the participants had First School Leaving Certificate (n = 0. 0%) (Table 3).

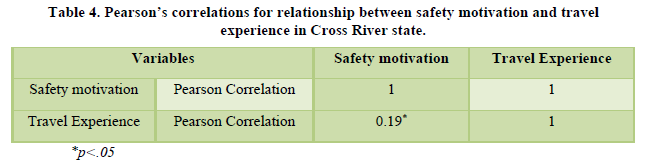

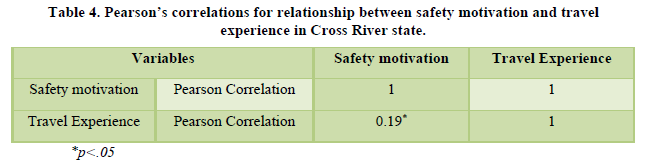

Table 4 indicated that there was a significant relationship between safety motivations and travel experience in Cross River state (r = 0.19, p<0.05). Specifically, higher safety motivation was associated with higher travel experience among the participants. Hence those who reported higher perceptions of safety were more likely to have positive travel experience.

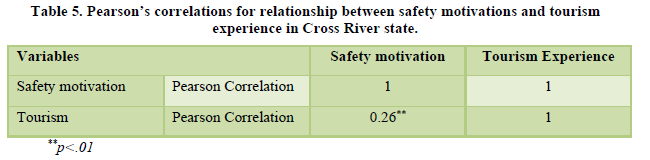

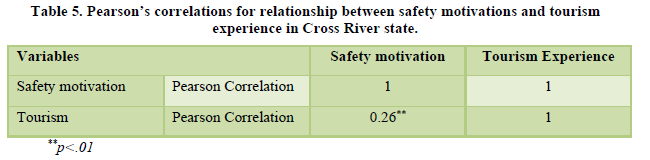

Table 5 indicated that there was a significant relationship between safety motivations and tourism experience in Cross River State (r = 0.26, p<0.01). Specifically, higher safety motivations were associated with higher tourism experience among the participants. Hence those who reported higher perceptions of safety were more likely to have positive tourism experience.

Majority of the participants strongly agreed that they have travelled across Cross River State within the last six months (n = 55, 51.4%). Five respondents (4.7%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 44.55, p(Table 6).

Majority of the participants strongly agreed that they have travelled across Cross River State within the last three months (n = 56, 52.3%). Five (4.7%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 43.97, p<.001.

Also, most of the participants strongly agreed that they have travelled across Cross River State within the last one month (n = 58, 54.2%). Five (4.7%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 62.39, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was high patronage at tourist sites in Cross River State (n = 55, 51.4%). Four (3.7%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 59.03, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was huge traffic of international tourists at tourist sites in Cross River State (n = 55, 51.4%). Six (5.6%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 57.48, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was increase in the rate of domestic travels in Cross River State (n = 57, 53.3%). One (0.9%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 64.32, p<.001.

Majority of the participants agreed that they have visited not less than one of the tourists sites in the last 3 months in Cross River State (n = 69, 64.5%). Three (2.8%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 63.24, p<.001.

Majority of the participants agreed that they have visited not less than one tourists sites in the last 6 months in Cross River State (n = 63, 58.9%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 64.70, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was increase in international travels to Cross River State (n = 69, 64.5%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 69.84, p

Most of the participants agreed that there was sustainable growth for tourism in Cross River State (n = 56, 52.3%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 68.91, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was huge investment for tourist sites in Cross River State as a result of high patronage by visitors (n = 57, 53.3%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 68.84, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was high patronage at tourist sites in Cross River encourages development of many other tourist sites in the state (n = 59, 55.1%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 71.39, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that there was huge patronage encourages transportation business in Cross River State (n = 59, 55.1%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 71.39, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that safety guarantee encourages huge international arrivals to Cross River State (n = 67, 62.6%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 69.41, p<.001.

Most of the participants agreed that safety guarantee encourages public and private sector investments in Cross River States tourism industry (n = 77, 72.0%). None (0%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 75.19, p<.001.

Majority of the participants agreed that there was much presence of both domestic and international tourists and other visitors at tourist sites in Cross Rive State (n = 68, 63.6%). One (0.9%) strongly disagreed with the statement. The differences in the responses was significant, t (1, 106) = 54.05, p<.001.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The first objective of the research was to understand the relationship between safety motivation and travel experience, Table 4, Pearson’s correlation for relationship between safety motivations and travel experience shows that there is significant relationship between the two variables. This implies that higher safety motivation breeds higher travel experience. That is to say that people travel more in the state when they feel a higher level of safety guarantee for such travels. This was also shown in 1, 2, and 3 item statements in Table 6 which was used to test the frequency of travel. Most of the respondents claimed to have travelled more frequently. The implication is that there is moderate safety guarantee for travels in the state. During the interview sessions, over 70% of the informants claimed to have travelled more within the state in the last one year because of the feeling of moderate safety guarantee. It was only a minute percentage (less than 30%) of these informants that claimed to have travelled out of necessity not minding the safety threats. Some of the previous literatures support this view by noting that adults and other travelers tend to travel more when there is feeling of high or moderate safety guarantee (Breda & Costa, 2005; Gram, 2005; Breda & Costa, 2005; Law, 2006; Correia, Oom do Valle & Moco, 2006; Kozak, Crotts & Law, 2007; Beirman, 2009; Popescu, 2011; Brock, 2014).

Moreover, the second objective of the study was to understand the relationship between safety guarantee and tourism experience among the study sample. Pearson’s correlation for relationship between safety motivation and tourism experience as can be found in Table 5 shows that there is a significant positive relationship between the two variables. This implies that high safety motivation translates to high tourism experience in the state among adults. In Table 6, Item statements 4, 7, 8, and 11 were used to understand the frequency of visits to tourist sites in Cross River State among adults. A greater percentage of respondents informed that there is high patronage at these tourist sites as a result of high tourist flows to the state. Also, that this has motivated sustained tourism investments in the state. This was equally confirmed during field visits to these tourist sites in the state. In addition, during in-depth interview sessions, informants agreed that there is traffic to these sites by both local and foreign visitors/ tourists. Few of the informants who claimed not to have frequency visits to the sites attributed that to financial constraints and lack of leisure time, for such visits and not necessarily on the safety issues. The implication of this result is that there is reasonable safety guarantee at tourist sites in Cross River State. Similar studies also agreed with this fact by noting that tourist destinations with moderate safety guarantee stand more chances of having more tourist traffic than counterparts with less safety guarantee (Kim & Chalip, 2004; Dolnicar, 2005; Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Lepp & Gibson, 2008; Chon, 2012).

Finally, this last objective of the study was to understand the implications of safety motivation for travel and tourism experience for domestic and international tourism experience in Cross River State. In Table 6, Item statements 5, 6, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15 & 16 were used to investigate these implications. And the result shows that there is huge traffic for both domestic and international travels to the state, motivated sustainable tourism growth, development of more tourist sites in the state, and increased transportation business among others. A greater percentage of responses affirmed these implications during the quantitative survey. Also 85% of the informants agreed that there is increased traffic for both domestic and international tourists to the state, and increased tourism investment from both the public and private sectors. This informs that there is reasonable safety guarantee to visitors in the state since tourists are not motivated to visit risk-prone destinations (Obieluem, Anozie and Nwankwo, 2016; Nwankwo, 2017). During field observations it was discovered that most of these tourist sites in the state record huge tourist flow. The implications of this result is that reasonable safety motivation has greater positive implications for sustainable tourism growth and development in a given tourist destination (also see Crompton, 1979; Cossens & Gin, 1995; Floyed et al., 2004; Venkatesh, 2006; Chang, 2007; Kozak et al., 2007; Chi & Qu, 2008; Hu & Bai, 2013).

CONCLUSION

Safety factor has been identified as among the major challenges of travel and tourism industries across the globe. This study was focused on addressing safety motivation for travel and tourism experience and the implications of this for domestic and international tourism experience in Cross River State, Nigeria. The result of the study revealed that there is a significant relationship between safety motivation and travel/tourism experience. This was supported by Dann’s Theory of Push and Pull Motivations (Dann, 1996) and Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs as was proposed by Maslow in 1943. This implies that safety motivation has a lot to contribute to sustainable tourism development. Safety motivation is among the central points in making considerations for choice, decision and frequency of travels and visits to tourist sites (Jennings, Sook, Ayling, Lunny, Cater & Ollenburg, 2009). The study further buttress that there is reasonable safety guarantee for travel and tourism experience in Cross River State as was determined through patronage. The implications being that not minding the activities of militants Cross River State has moderate safety guarantee for travellers and tourists.

However, to promote sustainable domestic and international travel and tourism experience in Cross River State, there is need for a concerted effort from both the public and private sectors to enhance safety guarantee at tourism sites to motivate huge tourist traffic which has great implication for sustainable tourism development (Jackson, White & Schmierer, 1996; Decrop, 2006; O’Dell, 2007; Cooper & Hall, 2008). There is also a need to establish functional safety units at these tourist sites in Cross River state to monitor safety levels in the sites, collect safety data for safety analysis, and regularly redesign existing safety policies in the site to measure up with the current situation in safety discuss. Such efforts should also be extended to various travel routes in the state to enhance domestic travels within the state. An improved safety guarantee for travel and tourism experience in Cross River State would add more positive transformation to the economy of the state in the post COVID-19 pandemic regime in the state.

- Abomaye, N., Williams, A.S., Abomaye, N., Tamunobarasinpiri, C.E. & Iyerikabo, H. (2018). The activities of Niger Delta militants: A road map to development. Global Journal of Human Social Science; Economics 18(6), 45-60.

- Adegun, B.O., Joseph, A. & Adebusuyi, A.M. (2019). Housing affordability among low income earners in Akure, Nigeria. A Conference paper presented at the first International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructural Development, pp: 1-7.

- Aduwo, E.B., Edewor, P.A. & Ibem, E.O. (2016). Urbanization and housing for low income earners in Nigeria: A review of features, challenges, and prospects. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 7(351), 347-357.

- Aluko, O. (2012). Impact of poverty on housing condition in Nigeria: A case study of Mushin Local Government Area of Lagos State. Journal of African Studies and Development 4(3), 81-89.

- Anunobi, H.N. & Odum, C.J. (2019). Urban transport and its impact in tourism industry, Port Harcourt Rivers State, Nigeria. A paper presented for the 2019 ATDiN Conference Proceedings, pp: 9-22.

- Aribigbola, A. (2009). Housing affordability as a factor in the creation of sustainable environment developing world: The example of Akure, Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Science 5, 93-103.

- Beirman, D. (2009). Medical: Pandemic Threat: Tourist Industry Nightmare? Tourism Review, 36-45.

- Breda, Z. & Costa, C. (2005). Tourism, Safety and Security: From Theory to Safety. MA: Elseview Butterworth-Heinemann, pp: 187-208.

- Brock, J. (2014). Ebola fears slowing tourist flow to Africa. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-ebola-africatourism/ebola-fears-slowing-tourist-flow-to-africa-idUKKBN0GK1GG20140820

- Castelli, F. (2018). Drivers of migration: Why do people move? Journal of Travel Medicine (2018), 1-7.

- Chang, J.C. (2007). Travel Motivations of Package Tour Travelers. Original Scientific Paper 55 (2), 157-176.

- Cooper, C. & Hall, M. (2008). Contemporary tourism: An international approach, London, Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Correia, A., Oom do Valle, P. & Moco, C. (2006). Why People Travel to Exotic Places? International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality 1(1), 45-61.

- Crompton, J.L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research 6(4), 408-424.

- Chi C.G.Q & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management 29, 624-636.

- Chon, K.S. (2012). Tourism destination image modification process. Tourism Management 12, 68-72.

- Cohen, E. (2012). Toward a sociology of international tourism. Social Research 39(1), 164-189.

- Cossens, J. & Gin, S. (1995). Tourism and AIDS: The perceived risk of HIV infection on destination choice. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 3(4f), 1-20.

- Dann, G.M.S. (1996). Tourist motivation: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research 8(2), 187-219.

- Decrop, A. (2006). A grounded typology of vacation decision-making. Tourism Management 26(2), 121-132.

- Dialoke & Edeja (2017). Effects of Niger Delta Militancy on the Economic Development of Nigeria (2006-2016). International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research 3(3), 25-36.

- Dolnicar, S. (2005). Understanding barriers to leisure travel: Tourist fears as a marketing basis. Journal of Vacation Marketing 11(3), 197-208.

- Eze, C.I.N. (2019). Transport development: It’s Impact on the tourism sector. A paper presented for the 2019 ATDiN Conference Proceedings, pp: 1-8.

- Floyd, M. F., Gibson, H., Pennington-Gray, L., & Thapa, B. (2004). The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 15(2-3), 19-38.

- Gberevbie, D.E (2010). Nigerian Federal Civil Service: Employee recruitment, retention and performance. Journal of Science and Sustainable Development 3(2010), 113-126.

- George, R. (2005). Tourist's perception of safety and security while visiting Cape Town., Tourism Management 24, 575-585.

- Gnoth, J. (1997). Expectations and Satisfaction in Tourism: An Exploratory Study into Measuring Satisfaction. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Otago, New Zealand.

- Gram, M. (2005). Family holidays. A qualitative analysis of family holiday experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 5(1), 2-22.

- Han, H., Kim, W. & Kiatkawsin, K. (2017). Emerging youth tourism: fostering young travellers’ conservation intentions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 34(7), 905-918.

- Huang, A. & Xiao, H. (2000). Leisure-Based Tourist Behavior: A Case Study Of Changchun. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 12(3), 210-214.

- Hu, X. & Bai, K. (2013). A Study on the tourism destination image restoration scale: A contrast perspective of domestic and inbound tourists’ integration. Tourism Tribune/LvyouXuekan 28, 73-83.

- Iwuagwu, B., Onyegiri, I. & Iwuagwu, B. (2016). Unaffordable low-cost housing as an agent of urban slum formation in Nigeria: How the architect can help. International Journal of Sustainable Development 11, 5-6.

- Jackson, M.S., White, G.N. & Schmierer, C.L. (1996). Tourism experiences within an attributional framework. Annals of Tourism Research 23(4), 798-810.

- Jennings, G., Young-Sook, L., Ayling, A., Lunny, B., Cater, C. & Ollenburg, C. (2009). Quality tourism experiences: Reviews, Reflections, Research Agendas. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 18, 294-310.

- Kim, S.S. & Chalip, D.B. (2004). The influence of push and pull factors at Korean national parks. Tourism Management 24, 169-180.

- Kozak, M., Crotts, J.C. & Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travelers. International Journal of Tourism Research 9(4), 233-242.

- Law, R. (2006). The perceived impact of risks on travel decisions. International Journal of Tourism Research 8(4), 289-300.

- Laws, E. (1995). Tourist destination management: Issues, analysis and policies. London: Routledge.

- Lepp, A.N. & Gibson, H. (2008). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606-624.

- Magbadelo, J.O (2016). Reforming Nigeria’s Federal Civil Service: Problems and prospects. Indian Quarterly 72(1), 75-92.

- March, R.G. & Woodside, A.G. (2005). Tourism Behavior: Travelers’ decisions and actions. Cambridge: CABI Publishing, Cambridge.

- Moses, D. & Olaniyi, A.T. (2017) Resurgence of militancy in the niger delta region of Nigeria. Journal of Political Science and Public Affairs 5(4): 1-6.

- Neumayer, E. (2004). The impact of political violence on tourism- dynamic cross-national estimation. .Journal of Conflict Resolution 48(2), 259-281.

- Nwankwo, E.A. (2017). Fundamentals of tourism studies. Nsukka, University of Nigeria Press.

- Obieluem, U.H., Anozie, O.O. & Nwankwo, E.A. (2016). A study on safety and security issues at selected tourist sites in Eastern Nigeria. International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences (IJRASS) 9(1), 66-77.

- O'Dell, T. (2007). Tourist experiences and academic junctures. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 7(1), 34-45.

- Ogechi, I.A. (2019). Developing beach tourism in Unwana Golden Sand Beach: Its implications on the local community. A paper presented for the 2019 ATDiN Conference Proceedings, pp: 293-307.

- Oh, H., Fiore, A.M. & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research 46, 119-132.

- Paki, F.A.E. & Ebienfa, K.I. (2011). Militant oil agitations in Nigeria’s Niger Delta and the economy. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 1(5), 140-145.

- Popescu, L. (2011). Safety and Security in tourism. Case Study: Romania. Forum Geografic 10(2), 322-328.

- Richards, G. (2015). The new global nomads: Youth travel in a globalizing world. Tourism Recreation Research 40(3), 340-352

- Salau, T. (2015). Public transportation in metropolitan Lagos, Nigeria: Analysis of public transport user’s socioeconomic characteristics. Urban, Planning and Transport Research 3(1), 132-139.

- Sönmez, S.F. & Graefe, A.R. (1998b). Determining future travel behaviour from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research 37(2), 171-177.

- UNWTO Report (2016). Travel and Tourism: Economic Impact 2016 World.

- Venkatesh, U. (2006). Leisure: Meaning and impact on leisure travel behavior. Journal of Services Research 6(1), 87-108.

- Yoon, Y. & Uysal, M. (2005). An Examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management 26, 45-56.