Communication in tourism is essential. Sale of intangible products when purchasing requires the use of a wide range of elements of product presentation, a wide range of extremely markers that will be presented to potential tourists so that they can choose a destination in accordance with their expectations. How close or far from the truth is the image that tourists build for a chosen destination depends on the fairness, honesty and accuracy of semiotic language chosen by the bidder (Kolcun, Kot & Grabara, 2014). Tourism, when considered instrumentally, as a “mechanism” that a tool of “economic leverage” that transforms natural and cultural assets- “the sources”- to goods and services due to its very “nature”. Besides, series of problems emerge as: which of these natural and cultural assets will be part of valorisation and how. The chief problem occurs to challenge with is, the “nature” of tourism commercialization that the tourism assets highly depend on the cultural and symbolic world of a given place. In other words, the touristic goods and services are almost unconceivable commodities without their unique socio-cultural habitats (Sezerel & Taşdelen, 2016). The escalation of the mass tourism generated a widespread phenomenon, so called the tourist gaze (Urry, 1990), to educate and discipline the modern tourists on what to look and how to look at the things that are organised for their pleasure. This organization around the touristic attractions are needed to be promoted to receive tourists from all over the world. The attractions in tourism industry have their marketing and promotion strategies to attain a place in the market. Possessing solely a set of touristic assets (natural, cultural, etc.) is not adequate for attracting tourists and the methods to stimulate tourist’s attention comes into prominence. Then one is compelled to ask: “Why should I visit this destination?” The industry is already prepared to provide some objects to respond proactively: the tourism promotional materials (Sezerel & Taşdelen, 2016).

In this paper, we deal with the issue of the effectiveness of communication in tourism or its contents, which are seen from a different perspective, with an emphasis on strategic communication and its semiotic immanence. The content of the communication process in the tourism industry are the messages transmitted towards the tourist market. In tourism, the key messages are the tourism slogans of the destinations that seek to position themselves strategically through advertising. Therefore, this paper will be followed by the of advertising in tourism and its purpose to present a clear and convincing message (a slogan), to the market. Advertising is, in fact, information communication and tourism is important because of the perceptive planning of communication. Since without content there is no communication, there is a question of its comprehensive understanding so that tourist destinations communications can achieve the set goals through slogans. For that reason, this paper is specifically focused on the study of tourism slogan from a semiotic perspective. Specifically, we will try to view a complex issue of tourism advertising as an integral part of the promotional mix (Harrel, 2008) from a different perspective.

SEMIOTICS AND ADVERTISEMENT

The semiotic analysis of an advertising spot (both verbal and non-verbal) centers on the following elements: Color, logo and intonation. Color is a visual symbol of communication that creates the right atmosphere for the acceptance of the advertised product, leading the receiver’s eye through its contours and projecting a powerful and idealized form of the product. The logo characterizes the products or services of a firm-organization. It can be either verbal (consisting of one or more words-phrases) or composite (including a combination of words-phrases, images-designs and sound). Intonation conveys the transmitter’s attitude towards the transmitted message to the receiver and modifies the degree of informativeness of the advertising message (Poulios & Senteri, 2016).

SEMIOTICS IN TOURISM

Methodology

In the following analyses, we focus on the sign–object relationship to demonstrate how a formal analysis based on the semiotic method can provide both academics and destination marketers with an interpretive tool with which to identify any given representation’s complex sign-object relationship and with which to understand how that relationship conveys meaning(s) that can influence reception of the representation. In these formal analyses, we apply the semiotic method to representations used to market cultural and heritage tourism. In our interpretations of the photographs, we provide examples of how identifying the indexical aspects of a representation explain a representation’s potential to communicate messages about authenticity. We also provide examples of the way in which identifying iconic aspects can explain a representation’s potential to communicate familiarity. Finally, for each representation, we show how symbolic aspects of a representation can be interpreted to reveal multiple cultural and social layers of meaning. Each close reading suggests how the various aspects of the sign–object relationship often work in conjunction to generate hybrid meanings. Where relevant, the role of collateral experience as a prerequisite forgetting any idea signified by the sign will be noted.

RESULT AND ANALYSIS

Suspension bridge

Verbal signs in an advertisement are about texts. The texts in an advertisement explain the product and other terms which are supporting the product, for example the name of the product and the advantages of the product. Sometimes a text is hard to understand. In analyzing it, one person with the other can have different argument about it. Different people read and interest texts in ways, and it is possible to ask different groups of consumers how they interpret or understand a specific text. In the tourism brochures, visual sign become the major focus. The pictures as the visual sign can describe the product, the benefit of the product and what people could do through the product. Through the visual sign the audience can understand the meaning of the tourism brochures easily. Person who perform at the tourism brochures has important role to makes the audience attracted to the brochures. In order to understand the meanings of an advertisement in this case a tourism brochure featuring human subject we need to delineate the principle visual communication means by which people communicate. This picture takes from the cover one of the brochures in Meshginshahr county (Figure 1).

This means the advertiser wants to inform that attracts the readers not only to visit regency in Meshginshahr. The advertiser also wants to guarantee that the guests who came to the area will enjoy the beauty and exciting of the area. The visual signs in the this brochure show the beautiful area which is called The longest suspension bridge in the Middle East. This brochure can attract the tourist to come and join the tours, in this brochure most of the pictures are the real situation that can be found in the area. If we look inside of the page we can see a attract pictures of Meshginshahr city suspension bridge area.

Nomads of Shahsavan Meshginshahr

For example, we can see the nomads of Shahsavan Meshginshahr (Figure 2). The below picture we can see the local costume of the Shahsoon tribes, which is a symbol of beauty and simplicity. Life goes on according to their ancient customs and traditions. All the visual signs are match with the verbal sign and it’ make these brochures are so attractive for the tourist. Each brochure in this Travel has different pictures which are attractive picture so the readers can do something and understand between the texts and the pictures meant.

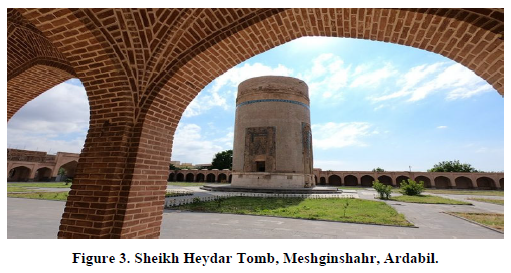

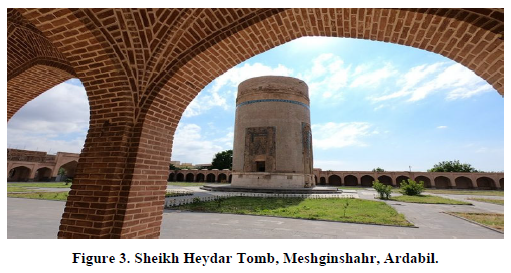

Sheikh Heydar Tomb

For iconicity to occur, the person whose interpretant completes the representation triad must be familiar with and recognize the object, and thus able to realize that the content of the photograph resembles the object photographed. The representation Brick structure with turquoise tiles conveys the structure’s historical accuracy: the object is a Brick structure; the architecture Sheikh Heydar Tomb is recognizably Safavid era. Thus, a potential tourist with the adequate collateral experience, considering traveling to Meshginshahr, would perceive not only a sign of an object that resembles tower; the tourist would readily see that the photograph depicts the old town tower lit up against an evening sky. Sheikh Heydar Tomb exemplifies the landmark as an iconic sign. Landmarks are unique cases of icons that are easily and quickly recognized as, for “a rare and treasured cultural resource”. Besides its iconic and indexical qualities, the photograph Sheikh Heydar Tomb also invokes a symbolic sign–object relationship, crucial to the successful marketing of heritage tourism. Any interpretation of that relationship draws heavily on those parts of a heritage tourist’s collateral experience, which allows him/her to associate and identify with related, real or imagined, cultural or historical contexts. Sheikh Heydar Tomb as a historic landmark, is likely to invoke a latent conception of a local past highly pertinent to some tourists. Depending on the tourist’s prior knowledge of relevant aspects of Safavieh history, can be a potent symbol of the Safavieh heritage, or of the process of maturation into nationhood (Figure 3).

This short analysis of a photograph of the Sheikh Heydar Tomb illustrates the relevance of analyzing destination representations with a view to potential semiotic interpretations of the sign–object relationship. Such detailed analysis would help destination marketers target with greater precision the desired audience of potential tourists and foretell, with some accuracy, the meanings the sign feeds into tourists’ destination images.

Shahar Yeri Ancient Site

In this example, the semiotic method is applied to the analysis of a photograph Shahar Yeri Ancient Site, as a representation of Ardabil culture. From a slightly high angle, the photograph captures include stones made by hand in shape of human form consisting of face without mouth, hands and sword. Ancient Site of Shahar Yeri, which dates back to 8 thousand years BC, includes hundreds of stones in shape of human. The photograph itself lacks certain indexical qualities, photograph of an old raised stone stands indicates nothing about the time or place that the photograph was taken. The objects in the photograph, though, have indexical qualities that signify their distinctness. Firstly, they are constructed from beech, although these are not simply wooden toy soldiers in any generic sense. They are a particular well-known kind. The human carvings on the stones are in the form of people holding hands to their chests with daggers and usually without mouths, and only one engraved statue of a woman has been found to have a mouth. The site contains 280 ancient man-made stones that are estimated to be more than 8,000 years old. The artifacts of this area date back to the Late Bronze, Neolithic and Late Copper periods, as well as the Early Iron Age. The artifacts of this area date back to the Late Bronze, Neolithic and Late Copper periods, as well as the Early Iron Age (Figure 4).

Fine dining in Gasabeh rural

Gastronomy has become an increasingly important component in marketing local attractions in tourism. Figure 5 is not an advertisement for itself or for any particular object represented in the photograph – not the entrées, not the families, not the Restaurant where the photograph was taken. It is an advertisement for dining out as such or more precisely, fine dining as a cultural experience awaiting the tourist who comes to Meshginshahr.

The composition of the image is traditional, with one table nearly center. The foreground is dominated by the several women, who are smiling. In the middle ground are the several men and the one woman, who is serving an additional portion, while the background is blurred by shallow focus, although other servers as well as the rest of the dining room remain indiscernible. There is no clear indication of either couple’s marital status, which allows the photograph to represent young unmarried or married couples at the same time, a reading that presumes the several families are sitting next to and not across from one another. The seating arrangement indicates at least partial adherence to the social custom of Observance of Islamic cover women. Their attire suggests that the four are middle to upper middle class (the only visible jewelry is a silver watch on one of the women’s arms). All four are relatively look healthy. Their expressions represent, as indeed they are surely intended to do, a pleasant moment shared by friends. At the same time, their social class, age, and attractiveness function to perpetuate a traditional objective of tourism advertising: Providing symbolic representations for status display that would otherwise be socially invisible in everyday life. In this case, the status is that associated with dining at a fine restaurant. The ability to recognize the dining situation in a photograph depends on iconicity and the ability of potential tourists to recognize familiar patterns of social behavior that conform to their collateral experience. Thus, the photograph subtly appeals to a potential tourist’s collateral experience of episodic information about eating at a restaurant, the cultural categories related to fine dining, and knowledge of or interest in ethnic foods fare served. It does so by iconically representing such disparate objects as water glasses, rice, patrons, and as well as symbolically representing imagined objects that are social concepts or cultural categories such as “having a good time” or leisure activities or lifestyle activities such as fine dining or dining in an restaurant. While leisure activities such as shopping and dining out must be represented by familiar – iconic – signs, they also have to be imbued with an aura of difference or exoticness, if they are to function as “pull” factors. In the photograph of the diners, the table presents the crowded, such as Each of the guests’ plates is visible, rice plate, barbecue plate is, visible as well as a bottle water in the middle of the table. As a whole, the symbolic opulence of the scene invites the potential tourist to participate in a “tourist culture that encourages people to behave in a hedonistic manner to a degree that may not be acceptable in their place of origin”. At the same time, the guests’ attire and demeanor, and the dignity of the architecture of the Patio dining room iconically assure the viewer that eating at the Gasabeh rural would be a gastronomical and not a Excellent experience. The attire, demeanor, and architecture also foreground indexical and symbolic aspects related to ethnic food and heritage tourism. In sum, this photograph serves to capture ritual at two levels: at that of the advertisement, which provides a “stylized presentation of tourism as a ritual activity” and, and that of dining out, which is itself a highly ritualized and culturally laden event. If “every tourist is a voyeuring gourmand”, the photograph represents the potential for an enjoyable culinary experience.

CONCLUSION

This article has shown how semiotic analysis can be applied advantageously in tourism studies. The representation triad was applied to destination representations by conceptualizing destinations, related activities, or entities as objects; photographs or textual descriptions as signs; and potential tourists’ comprehension of the sign as interpretants. Through analyses of photographs utilized in cultural and heritage tourism as well as national branding, it was emphasized that the sign–object relationship is always characterized by a combination of iconic, indexical, and symbolic qualities, each of which destination marketers should take into consideration because of the influence those qualities exert on reception. In sum, the semiotic model can assist marketers in making informed decisions about the relevance and probable impact of the iconicity, indexicality, or symbolism of representations, and helps to avoid conceiving of representations as if they were uniform and static rather than diverse and dynamic components in an ongoing process.

Adams, K.M. (1984). Come to Tana Toraja, “Land of the Heavenly Kings”: Travel agents as brokers in ethnicity. Annals of Tourism Research 11(1), 469-485.

Bandyopadhyay, R., & Morais, D. (2005). Representative dissonance: India’s self and Western representations, Annals of Tourism Research 32(4), 1006-1021.

Berger, A. (2004) Deconstructing travel: Cultural perspectives on tourism, Walnut Creek, CA, Altamira Press.

Bruner, E. (2005). Culture on tour: Ethnographies of travel, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cho, M. & Kerstetter, D. (2004) The influence of sign value on travelrelated information search. Leisure Sciences 26(1), 19-34.

Dann, G. (1996) The language of tourism. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International.

Echtner, C. (1999) The semiotic paradigm, Implications for tourism research. Tourism Management 20(5), 47-57.

Ge, J. (2017) ‘Humour in customer engagement on Chinese social media. Doctoral Dissertation Summary’. European Journal of Tourism Research 15(3), 171-174.

Harrell, G. D. (2008) Marketing, Connecting with Customers. Chicago, Chicago Education Press, John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Hunter, W.C. (2015) ‘The visual representation of border tourism: Demilitarized zone (DMZ) and Dokdo in South Korea’. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(2), 151-160.

Jenkins, O. (2003) Photography and travel brochures: The circle of representation. Tourism Geographies 5(3), 305-328.

Kolcun, M., Kot, S., Grabara, I. (2014) Use of elements of semiotic language in tourism marketing. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences 26(8), 1-6.

Krippendorf, J. (1987) Les vacances, et après? – Pour une nouvelle comprehension des loisirs et des voyages [English translation: The holidaymakers], Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan.

Lian, T. & Yu, C. (2017) ‘Representation of online image of tourist destination: a content analysis of Huangshan’. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 22(10), 1063-1082.

Lo, I. S. & McKercher, B. (2015) ‘Ideal image in process: Online tourist photography and impression management’, Annals of Tourism Research 52(9), 104-116.

Mehmetoglu, M. & Dann, G. (2003) Atlas/ti and content/semiotic analysis in tourism research. Tourism Analysis 8(3), 1-13.

MacCannell, D. (1999) The tourist–A new theory of the leisure class, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, [first edition 1976].

Metro-Roland, M. (2009) Interpreting meaning: An application of Peircean semiotics to tourism. Tourism Geographies 11(2), 270-279.

Mehmetoglu, M. & Dann, G. (2003) Atlas/ti and content/semiotic analysis in tourism research. Tourism Analysis 8(2), 1-13.

Moriarty, S. (2005). ‘Visual semiotics theory’, in Smith, K.L., Moriarty, S., Kenney, K. &Barbatsis G. (eds.), Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media. London: Routledge 227-224.

Peirce, C.S. (1991). Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic, Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press.

Poulios, I & Senteri, E. (2016). Branding Athens at a time of crisis: a semiotic analysis of the current tourism campaign of the historic city. Pharo 21(1), 37-56

Santos, C. (2004). Framing Portugal: Representational dynamics. Annals of Tourism Research 31(1), 122-138.

Sezerel, H., & Taşdelen, B. (2016). The Symbolic Representation of Tourism Destinations: A Semiotic Analysis. e-Consumers in the Era of New Tourism 10(5), 1-12.

Stepchenkova, S. & Zhan, F. (2013). ‘Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography’. Tourism Management 36, 590-601.

Sternberg, E. (1997). The iconography of the tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research 24(4): 951-969.

Tresidder, R. (2014). ‘The semiotics of tourism marketing’, in MacCabe, S. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Marketing. London: Routledge, 116-128.

Urry, J. (1990). The Tourist Gaze. London: Sage.

Zhang, X. & Sheng, J. (2017). ‘A Peircean semiotic interpretation of a social sign’. Annals of Tourism Research 64, 163-173.