Research Article

THE CONTRIBUTION OF FEEDBACK CONTENTS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF STUDENT THESIS: A CASE STUDY IN A TOURISM SCHOOL OF HIGHER EDUCATION

3203

Views & Citations2203

Likes & Shares

This paper aims to investigate feedback contents to improve the development of student thesis. This case study employed qualitative design that used multiple data collected from nine participants (six supervisors and three supervisees). The data were obtained from the textual evidence of students’ thesis drafts and in-depth interviews with the three students and their six supervisors. The data were analysed by labelling, categorizing and comparing for similarities and differences to uncover patterns and determine meanings. The results show that corrective feedback on writing mechanism gives less contribution to improve student thesis. Feedback of praise and criticism does not make a contribution to improving student thesis. Specific, descriptive and suggestive feedback on the concept and order of ideas indicates much improvement to the development of student thesis. The paper concludes that the feedback contents received from the supervisors determines student responses to improve the development of student thesis quality.

Keywords: Feedback, Thesis writing, Contribution, Contents, Development.

Supervisors’ feedback in thesis writing and its development is the main practices of thesis supervision. Feedback is an oral or written correction, critique or comment on student’s paper or a judgment about student’s writing performance (Leo, 2015). Feedback is very important for thesis students as it replaces the types of instruction received by students in lectures and classrooms (Bitchener & Basturkmen, 2006; Kumar & Stracke, 2007; Hyland, 2009; Bitchener 2011). It is also to help students improve their thesis to meet the standard criteria of thesis quality (Sharmini & Kumar, 2017, Leo, 2013 & 2017). Further, Engebretson (2008) and Bitchener (2011) stated that positive and comprehensive feedback from supervisors is essential to the effective completion and improvement of the thesis. The improvement of students’ thesis depends on how effective the feedback is provided. Feedback is effective when it communicates constructively to an individual or group regarding how their behavior and performance have been affected. Effective feedback is “positive, consistent, timely and clear, with a balance between positive and constructive comments and comments that critiqued their work” (Bitchener 2011). The effectiveness of feedback can be seen in the improvement or development of students’ drafts of thesis after being revised based on the feedback.

In many respects, feedback strengthens the type of instruction that students receive in classroom (Hyatt, 2005; Kumar & Stracke, 2007; Hyland, 2009). In thesis supervision, feedback creates writing knowledge as it indicated inherent pedagogical dimensions in the nature of research supervision (Engebretson, 2008 & Bitchener, 2011). In the process of writing thesis, students need to depend on feedback provided by their supervisors to receive input and guidance in order to improve quality of their thesis (Wang & Li, 2009). This process which provides an amount and quality of feedback is crucial in developing better understanding to be more process oriented, collaborating knowledge creation, and fostering independent learning among students as researchers (Lee, 2007). In other words, knowledge is produced within and through the feedback system, particularly when feedback is facilitated by nature, showing the intrinsic pedagogical characteristics of the nature of research supervision.

There have been a number of studies on writing feedback in different institutions. Sharmini & Kumar (2017) investigated examiners’ commentary on thesis with publications of health institution students. The findings indicated that they provide more feedback than summative assessment, and expected candidates to make changes on published papers. Azman (2014) examined supervisory feedback practices and their impact on student’s thesis development of Language Studies and Linguistics students. The findings direct in depth investigation of supervisory feedback practices towards framing an overall pedagogical approach to student supervision with the integration of effective supervisory styles. Mustafa (2012) and Buswell & Mathews (2004) investigated feedback on the feedback of Graduate School of Education students. The findings showed that students were very positive about a clear effort to make them read comments before receiving the mark and that the feedback they want is very distinct from what they receive. Sivyer (2005) examined the effect of positive/negative feedback awareness on self-efficacy and writing performance of educational psychology students. The findings indicated: a) positive feedback did not affect self-efficacy more than negative feedback; b) learners receiving feedback wrote less during the second learning period than they did before; and c) there was no statistical significance in the connection between feedback scores and performance scores. Alamis (2010) investigated students’ reactions and responses to teachers’ written feedbacks of university students. The findings showed that learners usually think that remarks from teachers help them improve their writing abilities. Patchan (2009) examined a validation study of students’ end comments of undergraduate history course students. The findings favored the use of peer review and the remarks of the learners appear to be quite comparable to the remarks of the teachers.

This paper intends to fill in the gap by investigating different types of feedback contents that are provided by supervisors and students’ responses to improve the quality of tourism students’ thesis. The contribution of feedback to the development of students’ thesis is indicated by the responses of the students to the feedback displayed by the revised drafts of students’ thesis. The results of this study will be more functional to enhance the quality of students’ thesis and will guide further in-depth inquiry of supervisory feedback practices as parts of general pedagogical strategy to the supervision of tourism graduate students by integrating efficient supervisory styles and communication techniques.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Literature reviews on writing feedback are focused on responses, comments, critiques or reactions to students’ drafts of thesis based on the interviews and documents of student drafts of thesis. Feedback content is effective when it indicates the most important points related to major learning goals to improve the quality of thesis, while less effective is when every error in writing mechanics is edited. Feedback contents provided by supervisors are classified into focus, comparison, function, valence, clarity, specificity and tone (Brookhart, 2008).

Focus feedback is provided on the work itself, on the process, and on the student’s self-regulation (Brookhart, 2008). On the work feedback is to indicate specific error types for correction. On the process feedback is aimed at the process used to create a product or a complete task or at the processing of information, or writing process requiring understanding or completing a task (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Self-regulation involves interplay between commitment, control, and confidence addresses the way students monitor, direct, and regulate actions toward the learning goal (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). It regulates autonomy, self-control, self-direction, and self-discipline. Focus feedback is effective when the information communicated to the students is intended to modify their thinking or behavior to improve learning (Shute, 2007).

Focus feedback applies to particular language forms such as spelling, capitalization, and punctuations or grammar, etc. Fazio (2001) & Sheen (2007) found that focus feedback is the most efficient in terms of improving writing mechanics. Further, Ferris (1999:8) stated that the lack of any form of grammar feedback could frustrate learners to the point that it might interfere with their motivation and confidence in writing. However, Truscott (1996: 328) argues that grammar correction is not important in writing courses and should be abandoned. For that reason, it is important to be selective to make the students not overwhelm with the amount of correction and to avoid over-attending to forms but respond more to concept and organizations or order of thoughts (Zamel, 1985) which are helpful to shape “an individual’s task strategy” to improve the quality of thesis (Early 1990: 103). Over attending to forms or writing mechanics is less effective in enhancing thesis quality than focusing on concept and arrangement of ideas or organization.

Comparison feedback consists of criterion reference, norm-reference and self-reference (Brookhart, 2008). Criterion-referenced feedback assesses whether a student has achieved the intended learning objectives and performance outcomes of a subject (Connoley, 2004). Thesis leaning objectives and outcomes are indicated in the guide book or school rubric in thesis writing. Knight (2001) found that the standard of the school rubrics has potential advantages as the assessment criteria is based on criterion reference. Norm-referenced feedback is comparing a student performance to other students. Kluger & DeNisi (1996) point out that students who have poor performance tend to attribute their failures to lack of ability and demonstrate decreased motivation on subsequent tasks. Self-referenced feedback provides information on how much students have improved by comparing their achievement with their past achievements (Youyan, 2013). In thesis writing, students’ achievements can be seen from the development of their drafts of thesis after getting feedback from supervisors. McColskey and Leary (1985) found that, compared to norm-referenced feedback, self-referenced feedback resulted in higher expectancies regarding future performance and increased attributions to effort.

Function feedback is to evaluate progress, performance or achievement, to encourage and support, and to learn high-quality work and how it might be achieved (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). The first feedback function is descriptive to indicate the specific standards for an excellent performance in which the successes and errors are identified and provides students a clear picture of their progress towards their learning goals and how they can improve (Jinguji, 2008). The second is evaluative to show how well student has performed on a particular task (Black & Wiliam, 1998). The next is corrective to support and to enhance the readability of the paper (Davies, 2003). For that reasons, teachers should reduce the amount of evaluative feedback and increase the amount of corrective descriptive feedback to improve student learning feedback.

Valence feedback refers to positive and negative feedback as an indication of emotional reactions (Frijda, 1986). Positive feedback needs to be credible and informative as negative feedback is likely to discourage motivation (Hyland & Hyland, 2001). However, Holmes (1988) found that positive feedback encourages the reoccurrence of appropriate language behaviors where writers are accredited for some characteristics, attributes or skills. Negative feedback demotivates students (Hyland & Hyland, 2006). Similarly, Karim & Ivy (2011) and Brockner (1987) suggest that negative feedback which is not constructive may make students lose their interest in writing and has the potential to elicit a wide variety of motivational responses. In fact, it may decrease, increase, or have no effect on individuals, depending upon certain situational and dispositional factors.

Clarity is clear message using simple written and spoken language for checking students’ developmental level and that they understand the feedback. Good clarity feedback uses simple vocabulary, writes or speaks on the student’s work, and checks student’s understanding. While bad clarity feedback uses big words and complicated sentence structure, shows what supervisors know and assume the student understands the feedback (Brookhart, 2008; Irons, 2007). Clarity includes showing the location of problems, providing comments in the margins, global comments at the end of a paper, and oral comments (Biber 2011). This is important to ensure the feedback is clear for in terms of the problems and space for writing the comments for revision.

Specificity is the level of information provided in feedback messages (Goodman, 2004). It does not only provide information about students’ accuracy but also provides more directive than facilitative information (Shute, 2007). It points to exact parts of the problems; is clear about what exactly the problem was; explains why it was a problem and makes the comments helpful (Nelson & Schunn, 2009). This kind of feedback is almost similar to clarity feedback but is more specific and students prefer to have this kind of feedback to improve or revise their thesis specifically. On the other hand, general feedback was not as effective as specific feedback (Williams, 1997; Fedor, 1991). It is because students are doubtful to give response to this feedback.

Tone fedback is conveyed by word choice and style. Word choice should take students into account and position them as active agents of their own learning (Johnston, 2004). However, rresearch shows that teachers often talk with good students as if they were active, but often do not care for poor students (Brookhart, 2008). Praise is almost similar to positive feedback. This feedback is quite often in the form of oral feedback commenting mostly on the attitude such as attendance/presence, behavior, or politeness and slightly on the work. It is not effective as it hardly carries information about thesis writing and often does not make students focus on the task (Brophy, 1981). Kluger & DeNisi (1996) in their research show that praise does not have significant impact on achievement. However, Gottschalk & Hjortshoj (2004) found that this kind of feedback encourages and motivates the students to accomplish the goals.

The theories of feedback contents above are the central issues which guide the researcher to design instruments to collect data. Data of interviews and document analysis are categorized into types of feedback contents that cover focus, comparison, function, valence, clarity, specificity and tone. The feedback from supervisors is to investigate contribution of feedback to the development of students’ thesis which will be indicated by the responses of the students to the feedback displayed by the revised drafts of students’ thesis.

METHODOLOGY

Data of this case study was collected by means of in-depth interviews with nine saturated participants and document analysis of students’ thesis from a leading tourism school of higher education in Indonesia. Morse (2015) takes the view that saturation is commonly considered as the 'gold standard' for determining sample size in qualitative research. The nine participants included six supervisors and three undergraduate students as supervisees, two supervisors supervised one student. Supervisors 1a and 1b supervised student number 1, supervisors 2a and 2b supervised student number 2, and supervisors 3a and 3b supervised student number 3. All supervisors were the most experienced lecturers whose teaching experience and thesis supervision for more than fifteen years and were appointed by their school managements to give supervision as the topics of the research were suitable for their expertise in tourism subjects. The three undergraduate (S1 degree) students were in their last semester out of eight-semester courses conducting research and writing their thesis. They were from three different study programs and were rated as the best students who gained the highest achievement in their study programs. This tourism school has been accredited by Tourism Education Quality under World Tourism Organization and belongs to the most senior school that becomes the model of other tourism schools in Indonesia.

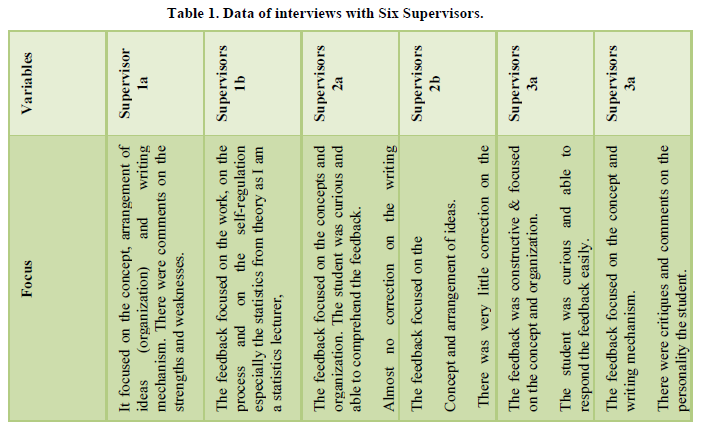

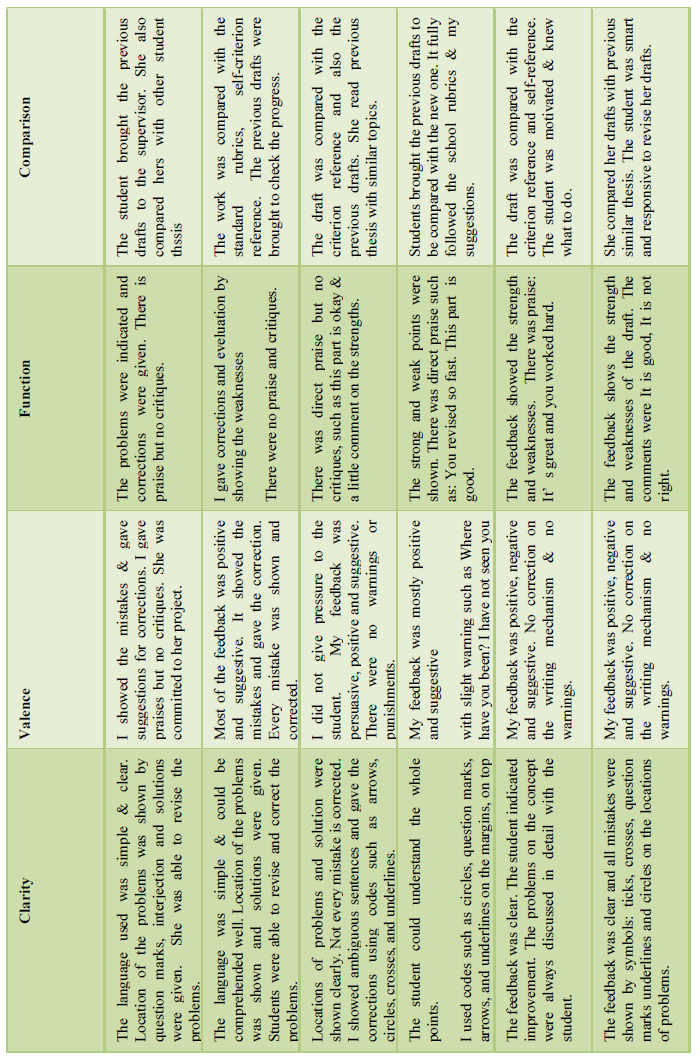

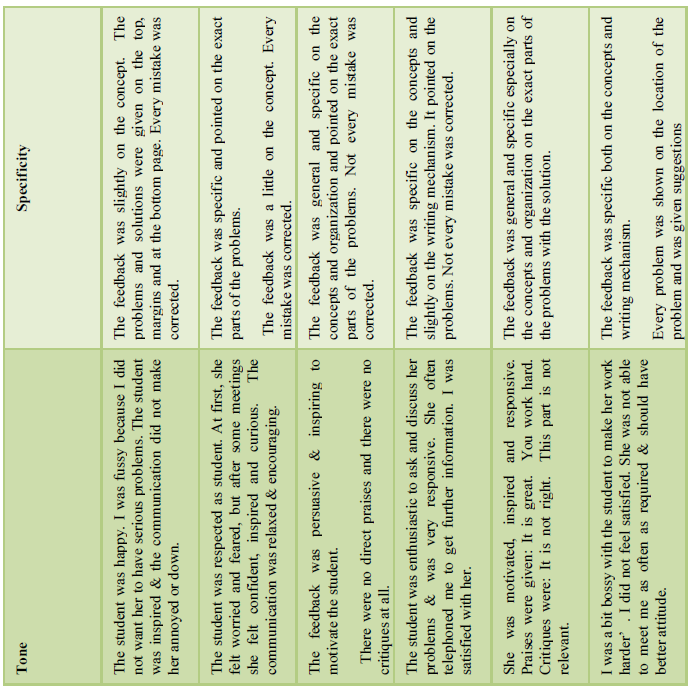

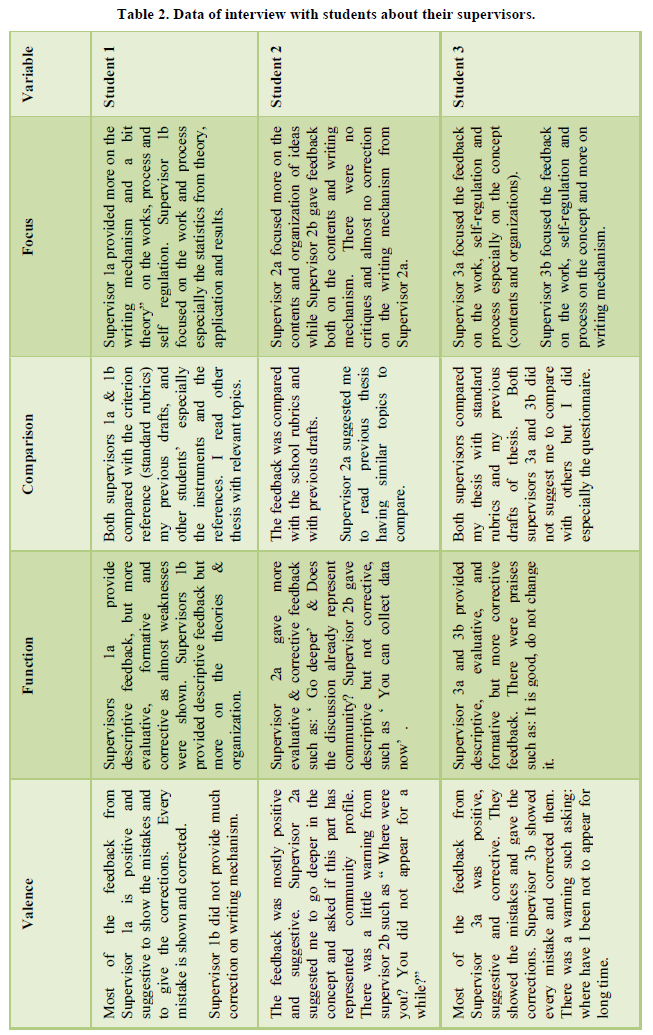

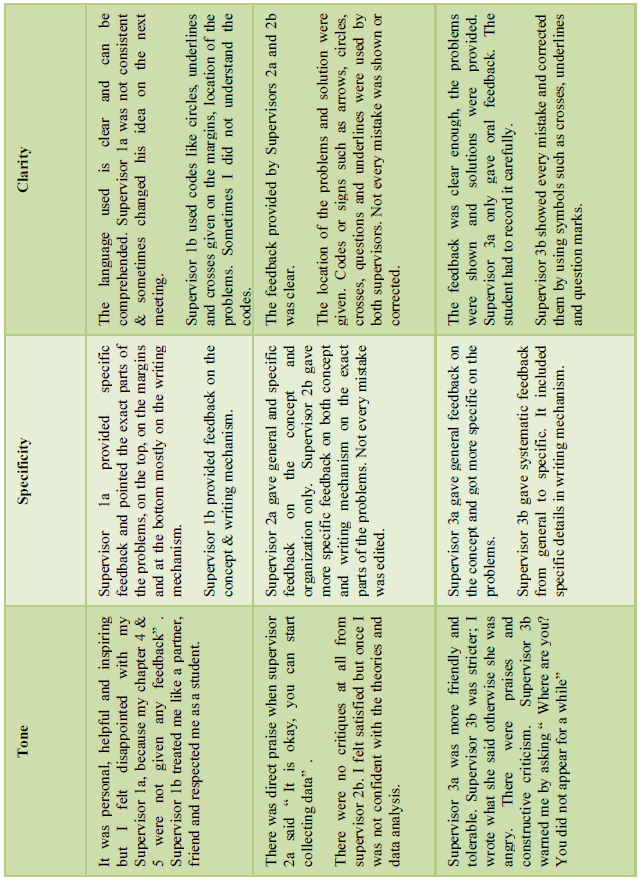

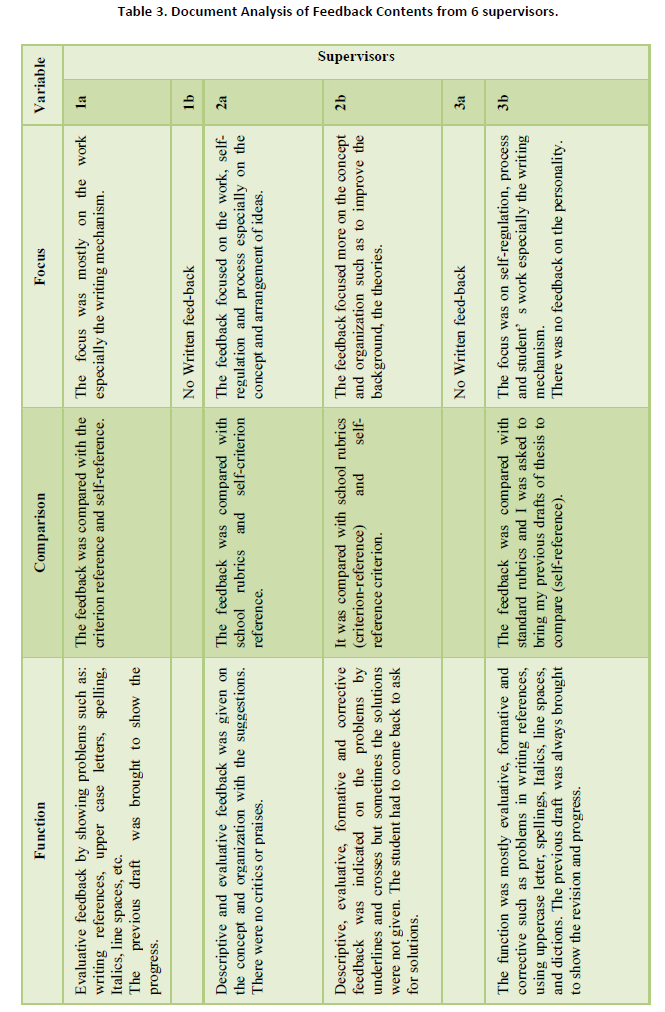

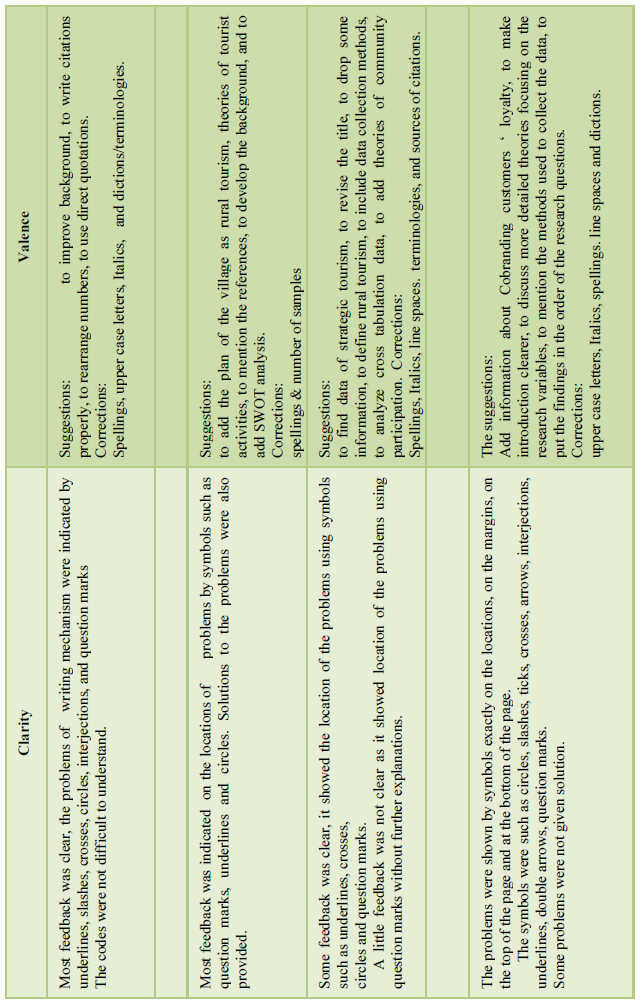

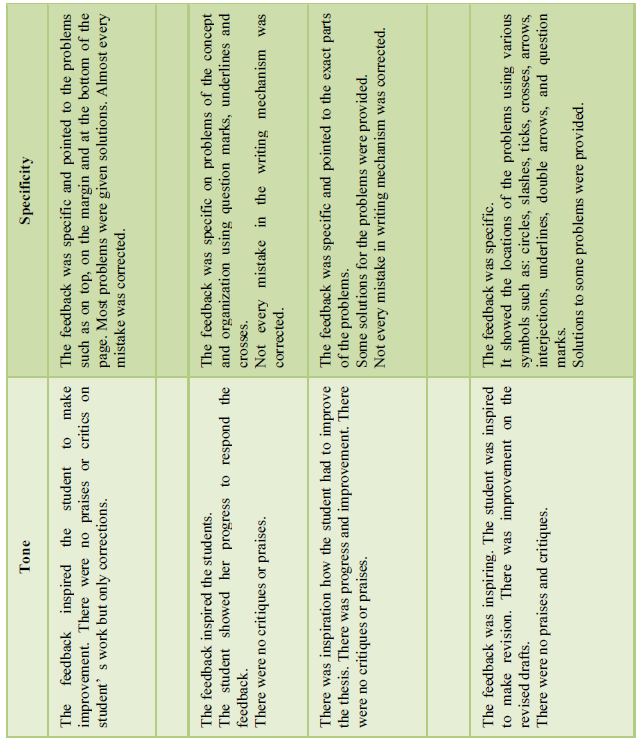

The interviews were conducted after supervisees’ drafts of thesis were returned to the supervisees with the supervisors’ feedback. The interviews were conducted face to face with the supervisors and supervisees individually and were recorded for analysis. The analysis was to identify the types of feedback contents that supervisors provided during the supervision process. The data of feedback contents from the interviews with the supervisors (Table 1) and supervisees (Table 2) was coded on the basis of focus, comparison, valence, function, clarity, specificity and tone. The data of document analysis (Table 3) was collected after students’ drafts were returned to the supervisees with the supervisors’ feedback and were revised. Two supervisors only provided oral feedback without written feedback on the drafts.

The analysis of feedback contents was carried out by the researcher alone to ensure the depth and consistency. The data of the interviews with supervisors and supervisees were reduced by selecting, simplifying, abstracting, and transforming the data that appeared in transcriptions in order to gain the meanings of the findings. To make a sense of the data, the coded data was compared within and across transcripts and across dimensions considered to be essential to the study. Finally, the data was interpreted by recreating the important codes and categories in a way that demonstrates the relationships and ideas obtained during the comparison phase and that explains them more widely in light of current information and theoretical views.

FINDINGS OF FEEDBACK CONTENTS

The findings of feedback contents from interviews with the six supervisors, three students and document analysis of the three students from their six supervisors are displayed separately below. The recorded data from the interviews were reduced, simplified and organized in accordance with the number of supervisors and supervisees based on the types of feedback contents being investigated. Table 1 displays feedback contents based on interviews with the six supervisors, table 2 displays feedback based on the interviews with the three students, and table 3 displays the six supervisors’ feedback on the three students’ drafts of thesis.

Table 1 shows data of interview about feedback contents provided by the six supervisors about their three students. The data was reduced, labeled and organized on the basis of focus, comparison, valence, function, clarity, specificity and tone.

Table 2 shows data of interview with three students about the feedback contents from their six supervisors (SPV). The data from the students were coded, organized and displayed in groups of focus, comparison, valence, function, clarity, specificity and tone.

Table 3 shows data of textual evidence based on students drafts of thesis about feedback contents from the six supervisors for their three students. The textual evidence was coded, organized, and displayed in groups of focus, comparison, valence, function, clarity, specificity and tone. There was no evidence of feedback on the students’ drafts of thesis from supervisors 1b and 3a as they did not give any written feedback. They only gave feedback orally to the students.

DISCUSSIONS

The discussions focused on the feedback contents based on interviews with their six supervisors, with the three students, and textual evidence of feedback contents on the students’ thesis from the six supervisors. The feedback contents were analyzed on the basis of focus, comparison, valence, function, clarity, specificity and tone in sequence.

The focus feedback revealed that all supervisors provided feedback on the work, on the process and on the self-regulation. Two supervisors (1a & 3a) focused on the work especially on correcting mistakes based on the interviews with the students. The evidence of writing mechanism corrections on the students’ drafts of thesis (except supervisors 1b & 3a) were such as misspelled words, uncapitalized words, line spaces, Italics, etc. This feedback that includes ideas to control form, and ability to use appropriate academic writing and research conventions was effective in line with Fazio (2001), Sheen (2007) and Goldstein (2006). They found that this feedback helped students improve their writing accuracy.

With regard to the feedback on the process, all supervisors helped students to process information to improve thesis quality and to complete thesis within the allocated time. The evidence of this encapsulated in the statements of supervisors and students. “When the student came to the next meeting, she brought the previous drafts of thesis with some revisions.”; “The supervisors guided me with the whole parts of the thesis, met me regularly and pushed me to complete on time.” Students admitted that his feedback helped them to go deep into the meaning not just surface structure. Such feedback is helpful to shape “an individual’s task strategy” (Early, 1990) to improve and complete students’ thesis.

Connected with self-regulation, all supervisors provided feedback to regulate student’s self-direction and self-discipline. The evidence of this was gathered from supervisors who said that students attended the meetings regularly and they were very enthusiastic and showed a great progress with their thesis and finished the thesis on time. And, it was evident from the feedback that the three students could finish their study on time. This evidence is consistent with the idea that self-regulation feedback involves interplay between commitment, control, and confidence addresses the way students monitor, direct, and regulate actions toward the learning goal (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

In short, on the work feedback that focused on the content quality and writing mechanism contributes to the development of contents and organization of ideas, convention, styles and tones of students’ thesis. The process feedback helps students to process the entire feedback. This feedback contributes to the development of the entire parts of students’ thesis. The self-regulation feedback helps students regulate their action to follow the standard of thesis writing and to complete their thesis on time. This feedback also contributes to the development and completion of their thesis.

For the comparison feedback, four supervisors compared students’ work with norm-reference and all supervisors compared students’ work with criterion-reference and self-reference. The evidence of interview with supervisors showed in what they said, “I also read previous thesis having relevant topics.” from a student, “When the topics are the same I asked the students to compare and discuss each other.” from a supervisor , “I sometimes asked her to compare with previous similar thesis.”, “The student was actually smart and she might have read the previous thesis.” Concerning the norm-refernce criterion, all supervisors asked the students to read and compare with the previous similar thesis. The students said that they actually read previous theses before deciding their topics and compared their drafts of thesis while writing the drafts. This approach was consistent with McColskey’s & Leary’s (1985) suggestion that norm-referenced feedback resulted in high expectancies regarding future performance and increased attributions to effort.

With regard to the criterion reference feedback, all supervisors compared students’ work with the school guidebook to write thesis. The evidence from students (1, 2 & 3) was such as “Both supervisors compared my thesis with the criterion reference (standard rubrics).”; “The feedback was compared with the school guide book”; “The feedback was compared with criterion reference (school rubrics/guide book) and ”; and “The feedback was compared with the school guide book (criterion reference) and self-reference.” In fact, both students and supervisors stated that they read and followed the guide book from the school. The guide book (rubrics) contains guideline of writing thesis that includes regulations, writing organization and mechanism. This feedback provides information by comparing student achievement with a learning target or standard (Youyan, 2013). These supervisors also suggested that the other students should follow the standard of the school rubrics. Knight (2001) suggests that the standard of the school rubrics (criterion-referenced assessment) has potential advantages as the assessment criteria clearly identify what is valued in a curriculum and identify exactly what learners have achieved, and it is possible to make judgments about the quality and quantity of learning.

The self-referenced criterion feedback was done as all supervisors always asked students to bring their previous drafts when they came to the supervisors. The evidence included such as “I asked my students to bring the previous drafts to compare.”; “Supervisor 3a compared my thesis with my previous drafts of thesis.”; “The feedback was compared with the students’ previous drafts of thesis.”; “The draft was compared with the criterion reference (school guide book) and students’ previous drafts (self-reference)” Here, students were able to show what they have revised based on their previous draft and the supervisors were able to see their progress. This evidence is relevant to Youyan (2013) that the feedback provided is indicated by information on how much students have improved their draft of thesis by comparing their achievement with their past achievements.

From the above discussion, the criterion reference feedback contributes to the thesis develoment according to the standard rubrics of the school. The norm-reference criterion make contribution to the development of students’ thesis on the parts that the students compared especially on the content quality. The self-referenced feedback makes contribution to the development of thesis both on the content quality and writing mechanism. The progress has been confirmed sufficiently in the revised drafts shown to the supervisors.

In the feedback functions, it was found that all supervisors provided descriptive, evaluative and formative feedback and four supervisors (1a, 2a, 2b, & 3a) provided corrective feedback. The descriptive feedback measures the specific standards for an excellent performance in which the successes and errors are identified to provide students with a clear picture of their progress towards their learning goals and how they could improve (Jinguji, 2008). The evidence of descriptive feedback were such as: a) to drop and change the research objectives, b) to develop knowledge and theory about service quality; and c) to inform the results of the research to the industry. This descriptive feedback helped students revise their next drafts following exactly what has been suggested by the supervisors. The more amounts of descriptive feedback that the students received, the more they learned significantly (Black & William, 1998). However, the descriptive feedback showed more on the weaknesses of the thesis drafts than the strengths of the thesis.

This evaluative feedback provided by all supervisors such as “I showed the mistakes and gave the corrections.”; “The feedback showed the problems of the content and organization.”; “My supervisor showed problems by codes such as underlines, crosses and question marks that I could not understand, then I had to come to get clarification”. The codes or symbols used were also such as: circles, slashes, ticks, crosses, arrows, interjections, underlines, double arrows, linking lines and question marks. Underlines, crosses and question marks were not effective or even useless for the students. This evaluative feedback is actually to correct the concepts and organization of ideas) and writing mechanism to improve students’ thesis Bitchener (2011) and Azman (2014) but the codes used by the supervisors did not help students.

Concerning the formative feedback, four supervisors (1a, 2a, 2b, & 3a) provided formative feedback with evidence such as: “a) to erase too general information, b) to include pages in the references for direct quotations, c) to include definition of rural tourism, d) to add definition of social assessment (not clear), e) to add factors of social assessment such as demography, socio-economy, local values, analyses stakeholder, etc., f) to add tourism product such as natural attractions, cultural attractions, cultural activities, facilities, and accessibility, g) to change tourism object into tourism attractions.” This formative feedback was effective as the students were able to improve their drafts based on the written comments from the supervisors. This evidence functions to communicate to the students what is intended to modify either the student’s thinking or behavior for the purpose of improving learning (Shute, 2007; Race, 2001). This formative feedback provided by the supervisors helped students revise and improve the contents and organization of their thesis and contributed to student learning. As the students acknowledged that this feedback was useful to improve the quality of their thesis drafts.

With regard to the corrective feedback, the evidence of the four supervisors (1a, 2a, 2b & 3a) provided corrections on students’ problems such as spelling mistakes, using upper case letters, using spaces, writing citation sources, and using italics. These conventional corrections are easy to understand in order to follow the conventions in writing. This evidence of corrections is consistent with Hefferman & Lincoln (1996) and Steel (2007) as to enhance the readability of the paper. This feedback contributes the development of student’s thesis in terms of the writing conventions but no contribution to the improvement of concept and organization.

Based on the discussion above, the descriptive feedback provided descriptions of strength and weaknesses of student performance in the forms of comments and suggestions, to contribute to the development of students’ thesis both on the content quality and writing mechanism. The evaluative or judgmental feedback that summarized how well the learner has performed using check marks or coded symbols such as crosses, underlines, circles, question marks, etc. contributes to the improvement of the thesis especially on the writing mechanism.

The formative feedback that provided comments and suggestions on the students’ works contributes to the development of students’ thesis through the provision of information about their performance. The corrective feedback that provided corrections of every error in writing mechanism contributes to the improvement of students’ thesis especially the writing conventions but is not effective to the content and organization of the thesis.

The valence feedback revealed that all supervisors provided positive and suggestive feedback and two supervisors (2a & 3b) provided negative feedback. The evidence of positive feedback from the interview with the supervisors is such as: I did not give pressure like my own students at Unpad. My feedback was mostly persuasive, positive and suggestive.” The positive feedback mentioned above provided ‘positive reinforcement’ that includes rewards, general praise, and that increases learner’s motivation (Brookhart, 2008). It is good to motivate learners to continue the work eagerly. It also helped students to reduce the amount of uncertainty associated with what students have to do or revise.

Two supervisors (2a & 2b) provided positive feedback with praises with evidence from statements such as: “It is okay, you can start collecting data.”; ‘It is great.’ and ‘You worked hard.’; “It is good, do not change it.”; “It is good.” These positive comments did not indicate any parts in the students’ drafts thesis for improvement. This kind of feedback may increase student’s motivation as they feel good or able to do something good. The students may be happy with it and gain more confidence. However, it does not give any contribution to the development of students’ thesis.

Concerning negative feedback or criticism from the two supervisors (2a & 3b). The evidence includes: “Where were you? You did not appear for a while?”; “Where have you been?”; “I have not seen you for long time”, “I also gave warnings to make her punctual and disciplined.” and “You cannot ask me to give 8 signatures when you came to me less than that.” These all negative comments refer to students’ presence, punctuality, and school regulation but they have nothing to do with their drafts of thesis for revision. It contains general criticism which was considered “punishment” and shows dissatisfaction of the supervisors with the students (Brookhart, 2008). The impact of this negative statement is relevant to (Hyland & Hyland, 2006) that it may demotivate students. The facts student three (3) for example was reluctant to see the supervisor 3b. Consequently, this student was the latest student who completed the thesis because of losing the interest in writing. This happened because she had difficulties to make appointment with the supervisors and demotivated to see the supervisors (Hyland & Hyland, 2006).

Connected with suggestive feedback from four supervisors (1a, 2a, 2b & 3a). The suggetsons include : a) to give more detail analysis for table of cross tabulation of education, occupation and income, b) to give line spaces for Local Socio politics, c) to include table of community value and needs, d) to analyze community value and needs in more detailed, etc. The suggestive feedback has a positive orientation as it can be incorporated into revisions to make the writing better (Brookhart, 2008). The development of student’s thesis occurs mostly on the revision of the content’s quality based on the comments, suggestions and corrections.

In summary, the positive comments that motivate, make students aware of the work, and encourage them to make in progress with the thesis writing contributes to the development and completion of students’ thesis. The negative feedback that contains general criticism and is considered as punishment does not make students lose their motivation, does not contribute to the development of thesis. The negative feedback does not help students take actions to revise the thesis and does not make contributions to the development of the students’ thesis both on the content quality and conventions.

The clarity feedback indicates that all supervisors who provided clear feedback, four of them (1a, 2a, 2b, and 3b) showed the locations of problems using codes or symbols on the locations of problem such as underlines, crosses, circles and question. The evidence of such comments includes: “It showed the locations of the problem by giving symbols such as crosses, underlines, ticks, circles, and question marks.”; “The feedback was clear; it discussed the problems found in the drafts and solutions were given.” The evidence indicates that the supervisors showed the problems clearly and gave the solutions to the problems. This evidence is in line with the ideas of Brookhart (2008) and Biber et al. (2011).

About the language used, the evidence is encapsulated in statements like “The words and sentences used were simple and understood by the student.” From the evidence above, the feedback was clear in terms of the simple language used and the written comments shown on the locations of the problems. This is in line with what Brookhart (2008) and Irons (2007) argue that the feedback in this writing supervision: a) uses simple vocabulary; b) writes and speaks on the student’s work; and c) checks that the student understands the feedback to improve their thesis. However, the feedback was less clear when the problems were indicated by interjections, underlines, and question marks without comments or suggestions. This happened to student one who sometimes did not understand the codes and had to ask for clarification.

In short, clarity feedback that uses simple understandable language and point out the locations of the problems with the solutions contributes to the development of students’ thesis. The less clear feedback with symbols or codes such as interjections, question marks or underlines without any comments or solutions on how to correct the problems, does not contribute anything to the development of thesis.

In the feedback specificity, all supervisors provided specific feedback with evidence such as “the feedback was specific and pointed the exact parts of the problems and provided solutions on the margins, on the top and and the bottom of the page.”; “The feedback was specific and pointed the exact parts of the problems but orally only.” The feedback was specific.”; “It showed specifically on the problems of the concept and organization.” The specificity of feedback that pointed the exact problems and the location (Nelson & Schunn, 2009) functions as expected. This feedback does not only provide information about students’ accuracy (writing mechanism) but is also more directive than facilitative (Shute, 2007). It provides detailed corrections of how to improve the quality, not just indicates the problems or mistakes on the student’s work.

Connected with general feedback on the contents from two supervisors (2a and 3b) that was indicated by question marks and interjections such as “Co-branding and affinity partnering? Loyalty? The introduction is not clear!” was not clearly understood by students. This feedback was not effective for students as it made them doubtful how to respond to the feedback (Williams, 1997; Fedor, 1991). This feedback needs greater processing activity on the students to understand the intended message. It took more time and energy as the students had to see the supervisors and asked what they meant.

From the above explanation, the specifity feedback shows the problems and the locations of the problems together with general feedback that is accompanied with specific feedback contributes to the students’ thesis development in terms of content quality and conventions, styles and tones.

In terms of tone feedback, it was found that all supervisors provided inspiring feedback, two supervisors (2b &3a) gave praises, and three supervisors 2b, 3a & 3b) provided critiques. With regard to the inspiring feedback by all supervisors, the evidence is such as “She sometimes telephoned or sent message to me to get some consultation about research methodology, etc.” and “The feedback was inspiring because the student was enthusiastic to ask questions and discuss her problems.” This feedback motivated the students to make progress with their theses and finally they were able to complete their theses on time. This evidence is consistent with Gottschalk & Hjortshoj (2004) who stated that this kind of feedback encourages and motivates the students to accomplish the goals.

With regard to the praises, there were two supervisors (2b and 3a) who provided feedback with praises such as ‘Bagus, kamu kerja keras” (It is great’ and ‘You work hard); ‘The recommendation is okay’ Praise, how small it is, belongs to positive feedback. This kind of feedback certainly increases learner’s motivation (Brookhart, 2008). However, praise is not always effective as it carries little information that provides answers and often disturbs student attention and becomes not focus on the task (Brophy, 1981).

Concerning feedback critiques from the three supervisors (2b, 3a, and 3b), the evidence was such as ‘It is not right’, ‘This part is not relevant’, ‘The recommendation is okay but you’d better provide more operational one.’ This kind of feedback (general criticism) was often considered as a punishment. The impact of critiques or negative feedback demotivated students. This evidence is consistent with Hyland & Hyland (2006) and Karim & Ivy (2011) that negative feedback which is not conveyed properly or if the criticism is not constructive, it makes students lose their interest in writing. In this study, however, the critiques do not have effect on individual motivation.

Based on the above discussion, tone feedback inspires and motivates students to work on their thesis contribute to the development of students’ thesis. Praising that may make the students motivated and confident does not contribute to the development of students’ thesis and critiques that may lose students’ interest and motivation do not have any effects on the contribution of students’ thesis.

To sum up the above discussion, it can be stated that each feedback dimension makes different level of contribution of ranging from low, medium and high contribution. Feedback focus, comparison, and function make high contribution to the student thesis development. Corrective gives low contribution. Positive and negative feedback has low contribution. However, suggestive feedback focusing on concept and organization makes high contribution to the thesis development. Similarly, clear feedback makes high contribution while unclear feedback does not make any contribution. Specific feedback also contributes highly to the thesis improvement and general feedback gives medium contribution. Finally, inspiring feedback has high contribution, but praises and critiques do not have contribution to the student’s thesis development (Hefferman & Lincoln, 1996, Wang & Li, 2009; Williams, 1997).

CONCLUSION

In this case study, feedback contents from the supervisors contribute to the developments of students’ thesis. The feedback is effective when it is specific, descriptive, and suggestive on the concept and arrangement of ideas. Specific feedback showing specific problems on the location of problems with descriptions and suggestions or solutions of the problems is very efficient in improving the quality of thesis. On the other hand, corrective feedback on writing conventions like the use of uppercase letters, Italics, misspelled words, and line spaces is less efficient in contributing to the enhancement of the thesis quality. While positive and negative feedback, including praise and criticism is not efficient in Improving the students’ thesis. The research concludes that particular, descriptive, and suggestive feedback on concept and arrangement of ideas is efficient in gaining responses from students that contribute to their thesis development. The enhancement of the students’ thesis is shown in the updated thesis drafts of the students. It is suggested that supervisors provide particular, descriptive and suggestive feedback on the concepts and organization of ideas. This study has the following consequences: a) Thesis writing guides, research methodology lecturers and supervisors are very important components to guide learners in producing standard thesis quality. Further study on how effective thesis-writing guidebooks, research methodology lecturers, and thesis- writing supervisors guide learners in writing is therefore crucial; b) All thesis supervisors were senior lecturers, however their perceptions in providing feedback are different. For this reason, it is essential to investigate the perceptions of thesis supervisors in providing feedback; c) As this qualitative research involved a limited number of samples, further quantitative research involving a representative number of respondents is recommended.

- Alamis, M.M.P. (2010). Evaluating Students‟ Reactions and Responses to Teachers‟ Written Feedback. Philippine ESL Journal, 40-57.

- Azman, H., Fariza, Nor, N.F.M., & Aghwelaa, H.O.M. (2014). Investigating supervisory feedback practices and their impact on international research student’s thesis development: A case study. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 141, 152-159.

- Biber, D., Nekrasova, T. & Horn, B. (2011). The effectiveness of feedback for L1-English and L2 writing development: A meta-analysis. (TOEFL iBT Research Report No. 14). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. Available online at: https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-11-05.pdf

- Bitchener, J., Basturkmen, H. & East, M. (2011). The focus of supervisor written feedback to thesis/dissertation students. International Journal of English Studies, 10(2), 79-97.

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment in classroom learning. Assessment Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

- Brockner, J., Grover, S., Reed, T., DeWitt, R., & O’Malley, M. (1987). “Survivors’ reactions to layoffs: We get by with a little help for our friends.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 32: 526-542.

- Brookhart, S. M. (2008). How to give effective feedback to your students. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 121.

- Brophy, J.E. (1981). Teacher praise: A functional analysis. Review of Educational Reseach, 51(1), 5-32.

- Buswell, J. & Matthews, N. (2004). Feedback on feedback! Encouraging students to read feedback: A University of Gloucestershire case study. The Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 3(1).

- Davies, A. (2003). Feed Back ... Feed Forward: Using Assessment to Boost Literacy Learning. Primary Leadership, 2(3), 53-55.

- Engebretson, K., Smith, K., McLaughlin, D., Seibold, C. Teret, G., et al. (2008). The changing reality of research education in Australia and implications for supervision: A review of the literature. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(1), 1-15.

- Fazio, L. (2001). The effect of corrections and commentaries on the journal writing accuracy of minority- and majority-language students. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(4), 235-249.

- Fedor, D.B. (1991). Recipient responses to performance feedback: A proposed model and its implications. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 9, 73-120.

- Ferris, D. (1999). The case for grammar correction in L2 writing classes: A response to Truscott (1996). Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(1), 1-11.

- Frijda, N.H. (1986) The Emotions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodman, J.S. & Wood, R.E. (2004). Feedback specificity, learning opportunities and learning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 809-821.

- Gottschalk, K, & Hjortshoj, K. (2004). The elements of teaching writing: A resource for instructors in all disciplines. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-101.

- Hefferman, J. & Lincoln, J. (1996) Writing: A concise handbook. New York: Norton.

- Holmes, L. & Smith, L. (2003) Student evaluation of faculty grading methods. Journal of Education for Business, 78(6), 318-323.

- Holmes, J. (1988). Doubt and certainty in ESL textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 91(1), 20-44.

- Hyatt, D.F. (2005). ‘Yes, a very good point!’: A critical genre analysis of a corpus of feedback commentaries on Master of Education assignments. Teaching in Higher Education, 10(3), 339-353.

- Hyland, K. & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students’ writing. Language Teaching 39(2), 83-101.

- Hyland, F & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the pill Praise and criticism in written Feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 79(3), 185-212.

- Irons, A. (2008). Enhancing learning through formative assessment. New York:Routledge. New York: Routledge.

- Jinguji, M. (2008) The importance of feedback: Descriptive and evaluative feedback. Available online at: www.innovations4pe.com

- Karim, M.Z. & Ivy, T.I. (2011). The Nature of Teacher Feedback in Second Language (L2) Language Classrooms: A Study on Some private universities in Bangladesh. Journal of Bangladesh Assosiation of Young Researchers, 1(1), 31-48.

- Knight, P. (2001). Formative and Summative, Criterion and Norm-Referenced Assessment, LTSN Generic Centre, Assessment Series No. 7.

- Kluger, A.N. & Denisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254-284.

- Kumar, V. & Stracke, E. (2007). An analysis of written feedback on a PhD thesis. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(4), 461-470.

- Lee, A. (2007) "How Can a Mentor Support Experiential Learning?", Journal of Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(3), 333-340.

- Leo, S. (2017) Mencerahkan Bakat Menulis, Jakarta: Gramedia.

- Leo, S. (2015) Thesis Writing Supervision: A contribution of feedback to the development of students’ thesis writing, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. Available online at: repository.upi.edu, perpustakaan.upi.edu

- Leo, S. (2013) Kiat Jitu Menulis Skripsi, Tesis dan Disertasi, Jakarta: Erlangga.

- McColskey, W. & Leary, M.R. (1985). Differential effects of norm-referenced and self-referenced feedback on performance expectancies, attribution and motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 10(3), 275-284.

- Morse, J.M. (2015). “Data Were Saturated . . ..”. Qualitative Health Research, 25(5), 587-588.

- Mustafa, R.F. (2012). Feedback on the Feedback: Sociocultural Interpretation of Saudi ESL Learners’ Opinions about Writing Feedback. English Language Teaching 5(3), 3-15.

- Nelson, M.M. & Schunn, C.D. (2009). The nature of feedback: How different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science, 8, 375-401.

- Patchan, M.M., Charney, D. & Schunn, C.D. (2009). A validation study of students’ end comments: Comparing comments by students, a writing instructor, and a content instructor. Journal of Writing Research, 1(2), 124-152.

- Race, P. (2001). Using feeedback to help students learn. The Higher Education Academy. Available online at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/id432

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., et al. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization, Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893-1907.

- Sharmini, S. & Kumar, V. (2017). Examiners’ commentary on thesis with Publications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(6), 672-682.

- Sheen, Y. (2007). The effect of focused written corrective feedback and language aptitude on ESL learners’ acquisition of articles. TESOL Quarterly, 41(2), 255-283.

- Shute, V. J. ( 2007). Focus on Formative Feedback. Princenton, NJ: Educational Testing Services.

- Sivyer, D. L. (2005). “The Effect of Positive/Negative Feedback Awareness on Self-Efficacy and Writing Performance”. Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations.

- Steel, Kimberly (2007) Definition for Writing Conventions. Accessed on: June 23, 2014. Available online at: kimskorner4teachertalk.com

- Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language Learning, 46(2), 327-369.

- Wang, T. & Li, L. (2009). International research students’ experience of feedback. Proceedings of the 32nd Higher Education Research Development Society of Australia (HERDSA) Conference, 6-9 July 2009, Darwin, Australia, pp: 444-452.

- Williams, S.E. (1997). Teachers’ written comments and students’ responses: A socially constructed interaction. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the conference on college composition and communication, Phoenix, AZ.

- Youyan, N. (2013). Using Feedback to Enhance Learning, National Institute of Education, Available online at: http://singteach.nie.edu.sg/issue40-research04/

- Zamel, V. (1985). Responding to student writing. TESOL Quarterly, 19(1), 79-101.