Research Article

Raising the EFLs Learner Autonomy Via Self-Awareness and Language Awareness Techniques

10492

Views & Citations9492

Likes & Shares

There has been a focus in the field of Applied Linguistics on developing autonomy among learners to promote success in language learning. Autonomous learners can use effective strategies, have appropriate knowledge, and hold positive beliefs and attitudes. Other factors related to success in language learning are self-awareness, a fundamental academic skill, and language awareness which is linked to conscious metacognition. This chapter aims to investigate whether the introduction of self-awareness and language awareness techniques to Grade Ten English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students can influence the development of autonomy. An intervention plan of 12 questions was implemented on 52 EFL Grade Ten learners in a private school in Lebanon. Results showed that the intervention succeeded in introducing self-awareness and language awareness to the learners, and with time students started showing autonomy. Accordingly, recommendations are made to introduce the two strategies into the national and school curricula at earlier school levels.

Keywords: Cognitive strategies, English as a foreign language, Learner-Centered Approaches, Learner independence, Metacognitive strategies, Self-Directed strategies, Student-Centered classrooms

INTRODUCTION

The crucial goal of education is “to produce lifelong learners who are able to learn autonomously” [1]. Holec [2] first introduced learner autonomy in the field of language learning in 1979 and defined it as “the ability to take charge of one’s own learning” and a potential capacity to act in a learning situation. Thaine [3] proposed that learner autonomy develops when learners begin to understand that they have a significant role to play in their own learning. This includes recognition of their needs, setting their goals, and finding the strategies that help them what and how them to learn.

Self-awareness and language awareness are two factors that are believed to play a significant role in the learners’ success in language learning. Price-Mitchell [4] stated that self-awareness plays a critical role in improved learning because it helps students become more efficient at focusing on what they need to learn. Bilash [5] suggested that focusing on language awareness helps in creating student-centered classrooms and assists the teacher to present material accordingly to student readiness.

This chapter attempts to investigate the success of implementing self-awareness and language awareness techniques to promote autonomy among learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) in Lebanon.

BACKGROUND

This section defines the three factors examined in this study: autonomy, self- awareness and language awareness and discusses how they have been implemented in the classrooms according to the related literature.

Autonomy

The concept of learner autonomy has developed from learners doing things on their own ‘for themselves’ [6]. Oxford [7] defined learner autonomy as the ability and willingness to perform a language task alone, with adaptability, transferability, reflection, and the intentional use of appropriate learning strategies. Liu [8] described autonomy as a construct of a sense of responsibility, involvement in tasks, and perceived ability. Little [9] identified the role of learners in the autonomy classroom as communicators in the target language (TL), experimenters with language, and intentional learners developing an explicit awareness of affective and metacognitive aspects of language learning. According to Colthorpe [10], learner autonomy is the learners’ capacity to take charge of one’s own learning, set appropriate learning goals, and construct knowledge from direct experience. Autonomy is not the learners’ self-instruction, nor an easily identifiable behavior, nor a steady state achieved by learners, nor the banning of the teacher’s intervention, nor a new methodology.

Independent learners use cognitive strategies and make use of techniques that they have stored and know are effective. For example, in order to comprehend and store information, independent learners take notes, summarize, and use charts, tables and graphs. To relate new information to their own prior knowledge, they use brainstorming techniques and create semantic maps. Independent learners also use metacognitive strategies; they plan, monitor and evaluate their language learning. They also arrange suitable conditions for learning, know how to monitor their writing and check their progress, and compare their self-assessment with other measures of proficiency [11].

Raising autonomy in the classroom

Autonomy has been examined in a number of studies. White [12] examined the influence of strategy used by 417 distance and classroom foreign language learners enrolled in a dual-mode institution. Findings showed that the mode of study influences most metacognitive dimensions of strategy use. Distance learners frequently used self-management metacognitive strategies and improved their self-knowledge. This urges the use of self-management strategies that improve a more autonomous approach to language learning. Cotterall [13] implemented a language course where the writers were provided a means of meeting their own needs. The findings from the observation of the students, their journals, and a written evaluation suggested that the tasks related to learners’ goals reflected a high level of motivation. Learners appreciated discussion of and solving problems, used ‘course’ strategies outside class, and improved their ability to assess their performance. Moreover, including material on learner strategies and the application of selected strategies helped in solving the problem of limited time, familiarized the learners with a problem-solving process, and helped them develop confidence in adopting strategies.

Liu [8] studied autonomy as a construct and its relationship with motivation among university freshmen students learning EFL. Findings suggested that the learners had a satisfactory level of autonomy when asked about their perceptions of responsibility, but an unsatisfactory level regarding engagement in learning activities. Motivation effectively contributed to predicting autonomy. Henriksen [14] reported the success of two complementary mindsets when students described their experiences: creative and reflective practice mindsets. The most successful was when they structured their interactions, and second was when they engaged in creative projects. The researchers recommended that autonomy be constructed through careful design in project work or interactions and communication.

Dam [15] proposed a simplified model for developing learner autonomy. In the center of the model, there are steps which are part of any teaching/learning environment: planning what to do, carrying out the plans, evaluating the outcome, deciding on the next step, and new planning. Since the aim in the autonomy classroom is to move towards a learner-directed environment, the learners are involved in managing their own learning process. However, there is constant interdependence between what the learners and the teachers do, such as in taking decisions regarding next steps. Moreover, students should be given choice which serves as a motivating factor in supporting their autonomy [16]. Katz [17] proposed that choice can be motivating when the options are relevant to the students’ interests and goals; meet the students’ need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness; are not too numerous nor complex; and are congruent with the values of the students’ culture.

For students to become more autonomous, Warren [18] suggested that teachers renounce control and give students responsibility. Teachers have to adjust the way in which they teach, moving away from deductive to inductive teaching of language skills. Warren [18] further suggested implementing flipped classroom lessons where students discover and learn the content at home. Moreover, the use of projects encourages students to work independently in pairs or small groups, develop 21st century skills, employ all four language skills, develop media literacy and increase motivation. Furthermore, students need to learn how to assess themselves and to do this honestly. Warren [18] suggested the use of Can-do statements at the end of a lesson for students to evaluate their work on a five-point scale. They can also learn to proofread their written work individually or in pairs and listen to their recorded speaking and evaluate it using criteria such as task achievement, fluency, accuracy and pronunciation. As to setting goals, students are helped to track progress, give a sense of direction and increase motivation. This can be done via statements that include specific goals related to certain tasks such as grammar, listening and reading. Mariani [11] illustrated with an example of students’ reading word by word aiming to understand or translate every word instead of implementing the prediction strategy to improve their reading speed and comprehension. A video without sound, or a photo story, is used for students to guess what the speakers are saying. Students say what has helped them to guess, they get feedback by watching the videotape with the sound on or see the story with the script and discusses why some guesses were incorrect. Then, they discuss how predictions are made, and whether they think prediction can be used while reading a text. Finally, teachers try to find out, through a brief discussion or questionnaire, if the learners use the strategy, when, how and why.

The strategies and techniques proposed above: cognitive and metacognitive strategies; planning, performing, taking notes, storing information, and keeping track of progress serve as a basis for the implementation plan.

Self-awareness

Self-awareness evolves during childhood, and its development is linked to metacognitive processes of the brain that develop after the age of three years [4]. When people focus on themselves, they compare their current behavior to their internal standards and values. They become self-conscious as objective evaluators of themselves [19]. Goleman [20] defined self-awareness as a person’s internal states, preference, resources, and intuitions. It is being aware and capable of monitoring one’s mood, emotion and thoughts about them. It is one of the four realms of emotional intelligence besides self-regulation, empathy, and social skill. People know that there are certain circuits that map their mental life via self-awareness. Self-awareness is a skill that people can learn; some people develop these mindsight map-making areas well and have good self-awareness. Besides being self-analytic, self-awareness is the presence of the mind to be flexible in the way people respond [20]. Weisinger [21] wrote that high self-awareness enables individuals to observe and monitor their behavior. According to Baron [22], self-awareness is a special type of schema that consists of all the knowledge we possess about ourselves. They maintain that this information is processed more deeply and is better organized than other information; thus, it is remembered more readily than other forms of information.

Rochat [23,24] proposed that self-awareness is of five levels that develop from birth to the age of 5 years. He stated that infants perceive their own bodies as differentiated, situated, and agent entities among other non-self-entities in the environment, namely physical objects and people from the first few weeks of life. Moreover, they develop rapidly a sense of themselves as perceived by others, i.e., "co-awareness", or the awareness of self in relation to and through the eyes of others. According to Eisenberg [25], self-awareness is the balancing and management of one’s emotions in everyday life. Effective learners successfully guide attention and intention towards the self as a doer,

thinker, and an evaluator and help yield academic and social goals set by self for self. Kamath [26] built on Premack [27] concept of the Theory of Mind which refers to the ability to attribute mental states, such as knowledge, to oneself and others. She hypothesized that a nurtured self-awareness can enable learners to make better decisions, manage stress, and establish purposeful self-advocacy. Self-aware students experience less anxiety and view challenges with a growth mindset when they recognize their own strengths and challenges. They seek help with a growth mindset when they learn to identify the nature of personal errors and accept them as part of learning new skills. And finally, they attune with others’ feelings and needs and begin to control their actions when they become aware of the impact of their own actions on others [26]. When students gain awareness of their own mental states, they begin to answer important questions about their own life, such as how to live happily, become a respected human being, and feel good about oneself and also to understand other people's perspectives. Self-awareness plays a critical role in improved learning because it helps students become more efficient at focusing on what they still need to learn. The ability to think about one's thinking increases with age, grows mostly around the age of 14 years. Furthermore, when students develop the metacognitive strategies related to students' schoolwork, they improve in reflecting on their emotional and social lives [4].

Raising self-awareness in the classroom

Kamath [26] suggested that teachers use self-awareness techniques to guide students to acquire Executive Function skills. These skills are self-management skills that help students succeed in achieving their goals. Students should be able to manage their emotions, focus their attention, organize their work and time, and revise their strategies [28]. Kamath [26] proposed that explicit development of students’ self-awareness influences their academic and personal lives. Through the following seven self-awareness techniques in the teaching model, a growth mindset and behaviors can be fostered to develop self-devised strategic thinking.

- Students note down and reflect on what they do well and what they find difficult to help themselves achieve their goals.

- Students identify and model emotions relating to skills assessment, task complexity and executionary demand through classroom conversations to help control and redirect emotions effectively.

- Students identify what causes stress and/or confidence and suggest strategies for defeating challenges to attain goals.

- Students listen to the teacher modeling a personal growth struggle. Then discuss, do the same, listen, restate the feedback, and reflect on the comments to develop their own action plan for improvement.

- Through reading and journal writing, students learn about others’ culture and environment by noting a character’s motives behind a certain action. And they consider their own motives for certain behaviors which influences their personality and actions.

- Students consider the reasons they are asked to do certain tasks, refer to the goals when doing assignments to see if they are on track, learn to manage distractions, and focus on the goals of each task.

- Students share opinions and become open minded and can formulate self-directed strategies when indulged in assignments where multiple opinions exist [26].

Kamath [26] concluded that through the direct and explicit teaching of Executive Function skills, students become aware of their and others’ strengths and challenges, and collaborative by exploring diverse ideas. They will be able to push their learning forward by understanding how to achieve their goals independently and collectively. Kamath’s [26] proposed techniques served as part of the framework for the implementation of the study in an EFL context promote self-awareness.

Language awareness

Carter [29] explained that the concept of language awareness was, in the 1980s, a reaction to prescriptive approaches, and at the same time developed a motivation to the neglect of language forms of some communicative approaches. Recently, it has progressed along language description which is larger than words- that of discourse, and it includes a cognitive reflection on language. Research showed learners’ increased motivation resulting from task-based activities which involve the learners in inductive learning specially of language forms. Language awareness has developed in all language learning contexts: first, second and foreign language contexts. Carter [29] defined it as the learners’ development “of an enhanced consciousness of and sensitivity to the forms and functions of language”.

Language awareness can be defined as the learners’ conscious development of and awareness of the forms, properties, functions and use of language in a comprehensive language education [29-31]. A focus on language awareness is a key aspect of creating student-centered classrooms and assists the teacher to present material accordingly to student readiness [5]. Language awareness allows the student to reflect on the process of language acquisition, learning and language use [32]. It improves the knowledge of the language acquisition and learning processes as it clarifies the similarities and differences between the learners’ native language and

the foreign languages [33]. Language awareness is composed of content about language, language skill, attitudinal education, and metacognitive opportunities which allow the student to reflect on the process of language acquisition, learning and language use. All these aspects of language awareness need to be integrated into the existing subject areas [32].

Bourke [34] proposed that language awareness in a foreign language context enriches a learner’s knowledge of the language as it helps to find out how language works and to reflect on the available linguistic data. The learners should be actively involved in discovering the language and the teachers help them to effectively explore, internalize, and acquire understanding of the TL.

Raising language awareness in the classroom

There are two views about developing language awareness. The first promotes an explicit focus on ‘how language works’ and encourages a structured and systematic language awareness-specific analysis of the meaning of discourse [33]. The second supports an incidental mentioning during lessons only when a topic lends itself.

Yang [35] investigated how 68 EFL college students in Taiwan improved their use of learning strategies through awareness-raising in group interviews and informal learner training. Results showed significant differences between students’ use of learning strategies in the pre-test and post-test. The Interactive discussion in group interviews helped to raise strategy-related awareness among respondents and improved their use of learning strategies in both frequency and variety. Bull [36] introduced learning style–learning strategies (LS-LS), an interactive learning environment to raise learner awareness of language learning strategies. Strategies of potential interest to a student are suggested based on the student's learning style, and similarities between new strategies and strategies already used by the individual. LS-LS is intended primarily for use in contexts where resources are limited. An initial study suggests that learners will find many of the strategy recommendations useful.

Garcia [37] proposed that language awareness in teaching includes three concepts: (a) knowledge of language, i.e., proficiency, the ability to use language appropriately in many situations, awareness of social and pragmatic norms, (b) knowledge about language, i.e., subject-matter knowledge, forms and functions of systems- grammar, phonology, vocabulary, and (c) pedagogical practice, i.e., creating language learning opportunities or classroom interaction. In a parallel way, Bilash [32] suggested a number of ways for students to build language awareness. They can examine their native language- structure and use, word order, word etymology, word formation and meaning. They may develop an appreciation for language in general and the TL specifically by developing the confidence to make an attempt or take a risk and become aware of strategies they can use to learn it. They will become more active and responsible for their learning. Moreover, language awareness is fostered when they integrate what they learn in other classes to TL learning. She further suggests activities: Open Discussion, Synonyms and Expressions, Social Register, Language Variation or Dialect, Cognates and Word Origins to increase the students’ own language awareness [32]. The similar propositions by Garcia [37] and Bilash [32] served as part of the framework for the implementation of the study in an EFL context to promote language awareness, besides Kamath’s [26] proposed techniques to promote self-awareness.

The role of the three factors

Reviewing the related literature on learner autonomy, self-awareness, and language awareness, which were mainly done on older learners and relate to the participants in this study, one can state that there have been various attempts to promote them to see their influence on success in language learning. Autonomous learners use cognitive and metacognitive strategies that guide them to plan, process and evaluate their learning process [11]. Researchers Dam [15], Warren [18], Ryan [16] and Katz [17] proposed classroom techniques and models to test the development of autonomy among learners. Cotterall [13] and Henriksen [14] reported the success of special programs that promoted autonomy.

Self-aware learners have skills such as how to perform better and be more efficient at the tasks they do which lead them to be better learners. Kamath [26] proposed the use of explicit self-awareness techniques to develop self-devised strategic thinking among learners that is expected to influence their academic and personal lives.

The learners who possess language awareness are conscious of the forms and functions of language; this consciousness allows them to reflect on their language acquisition and use. Researchers Bilash [32], Yang [35] and Bull [36] suggested interactive ways to raise learner awareness of language and language learning strategies.

Therefore, this study hypothesizes that developing autonomy via self-awareness and language awareness lead to success in learning English in a foreign language context.

Implementing an educational plan

Based on the literature on the concepts above, this study aims at implementing a plan to raise self-awareness and language awareness to attain autonomy among Grade 10 learners in an EFL context- Lebanon. The following section presents the problems related to developing learner autonomy, the context and elements of the study, and the findings and their analysis.

Issues in learner autonomy in an EFL context

The implementation of a program promoting learner autonomy may face some challenges. Learners are generally used to having a passive role at schools and hesitate to become responsible of their own learning, i.e., to set learning targets, select learning materials and activities, and evaluate learning outcomes [6]. Second, autonomy can take a variety of forms, depending on learning context and learner characteristics [38]. Learner autonomy was introduced and promoted by academics in the West. And since the approach to teach language awareness involves culture and social aspects, attempts to implement learner autonomy in EFL contexts may face difficulties [39]. Palfreyman [40] examined whether learner autonomy and culture interact in a range of learning contexts. He raised questions about the meaning of learner autonomy in the context of particular cultures, whether autonomy is an appropriate educational goal across cultures, and if so, how it can be enhanced in a variety of cultural contexts. Palfreyman [41] interpreted culture in three ways: (a) national/ethnic cultures such as “the West”, i.e., whether learner autonomy is ethnocentric, (b) values and customary behavior in different kinds of community, e.g., the culture of a school and a classroom; and (c) the learner in sociocultural context as opposed to in isolation which is associated with autonomy. Missoum [42] also examined the relationship between general and educational culture and autonomous learning among 35 teachers and 135 students in Algeria. Though the subjects showed positive attitudes towards learner autonomy, there was some uncertainty about the role of the educational culture in developing Algerian learners’ autonomy. Missoum [42] suggested that the general and educational culture must be taken into consideration in the implementation of reforms in education.

Lebanon is an EFL context for the teaching and learning of English where culture may be a significant factor in developing autonomy. This research study aims to answer the following research question: how does the implementation of self-awareness and language awareness techniques among EFL learners affect the development of their autonomy in the language learning process in Lebanon as an EFL context?

The context of the study

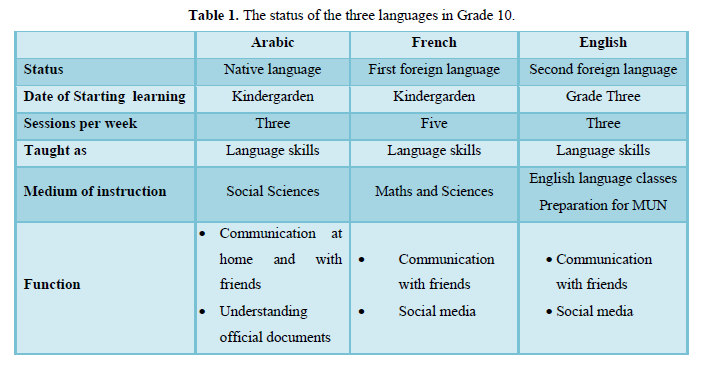

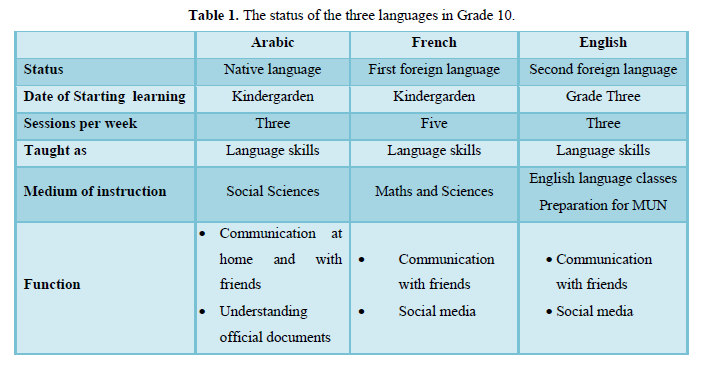

The study took place in a private school in Lebanon. The school gave consent to administer this study and publish the results. The native language of the learners is Arabic, and two foreign languages are taught; French and English. The former is the first foreign language and the medium of instruction for sciences and mathematics, and the latter is the second foreign language. It is here essential to describe the curriculum of English as a second foreign language in Lebanon.

The Centre for Educational Research and Development (CERD) founded the Plan for Educational Reform- 1994, and the New Framework for Education in Lebanon- 1995 [43]. The curriculum aligns with the current theories, findings in the area of second language acquisition, and foreign language curriculum design and teaching methodology. The curriculum attempts to develop the use of English for three major purposes: social interaction, academic achievement, and cultural enrichment. Some of the features of the new curriculum are: (a) students will learn content-related information while acquiring English language skills in listening, speaking, reading, and writing, in addition to thinking skills, (b) the new curriculum attempts to develop native-like proficiency in English- fluency first, then accuracy, and (c) language will be presented to students in its proper cultural context [43]. The curriculum specifies that English as a second foreign language is taught two hours a week in grades 7 through 12; yet private schools can assign more hours. Learning English as a second foreign language allows learners to follow university education through the medium of English and thus would be better prepared for future careers in the fields of trade and communication and of science and technology [43].

Though the Lebanese curriculum of teaching English reflects an ideal base for an effective learning, the researcher’s observation of the EFL classes in the school over a year did not reflect the principles of teaching a second foreign language as stated by CERD:

- Language learning is learning to communicate

- Language varies according to the context of communicative interaction

- Learning a new language is becoming familiar with a new culture

- Language learning is most effective when it takes place through meaningful, interactive tasks

- Language skills-listening, speaking, reading and writing are interdependent [43].

The reasons for the mismatch between the principles of the curriculum and their application in the language classroom may vary. There is the large number of students per class-around 30 who are seated in the traditional classroom arrangement of students in rows and columns, with the teacher in the front, and the blackboard in front. The number of language classes per week is low-3 classes and the skills are not integrated, i.e., each skill is taught separately per session. Moreover, the school and parents are not yet ready to accept a minimized teacher’s role in the classroom versus the learners’ and they still expect the educational system to focus on some skills like grammar and reading aloud, and on homework assignments.

It is here hypothesized that the EFL teacher's implementation of self-awareness and language awareness techniques in the EFL classroom affect the development of Grade 10 students' autonomy in language learning.

The study

The participants in the study were 52 Grade 10 students and their EFL teacher in a private school in Beirut. Grade 10 marks the beginning of the secondary level in the Lebanese curriculum, i.e., Grades 10, 11 and 12, and it is expected that by this level the students have developed appropriate language skills to be able to respond to a language awareness program and to be able to manifest it in the three secondary years before they graduate from high school and enter the university. The participants started learning English in Grade Three, so they have been studying it for eight years. In Grade 10, they study English three sessions every week as a second foreign language; the study includes reading and listening comprehension, oral communication, writing, and preparation for Model United Nations (MUN), a popular extra-curricular program in which advanced students at the school volunteer to role-play delegates to the United Nations every year. The program aims to develop a strong bond between the UN and Model UN participants across the globe through workshops and conferences [44].

The students' native language is Arabic, and they study it as a language three times a week during which they analyze Arabic literature texts. Arabic is also the medium of instruction for social studies: History and Geography, and later on in the future to understand official documents.

It is essential to state that French is the students’ first foreign language that they start learning when they enter school at the Kindergarten level, so they have been studying it for 12 years. They study it five times a week and it is the medium of instruction for Mathematics, sciences, Computer, Economics, Sociology, and ‘Travaux Personnels Encadres’ (TPE), translated as: Personal Supervised Work, one of the exams required to pass the French Baccalaureate at the end of the secondary cycle. So besides being subjected to French two additional sessions than the other two languages every week, many students use French for communicative purposes with the parents and siblings at home, with their friends outside the school setting, and in the social media. The following table presents the status of each of the three languages in Grade 10 (Table 1).

An intervention plan for the EFL classroom was adapted from Garcia’s [37] and Bilash’s [32] identification of the components of language awareness and Kamath’s [26] suggestion of the self-awareness techniques. This study adapted an explicit language awareness plan of 12 steps over four class sessions. The first three questions aimed towards promoting the subjects’ language awareness, and the rest aimed for promoting their self-awareness. The researcher met with the class teacher prior to the start of the intervention to discuss the plan and guide her into the implementation of the steps by providing the points for discussion and some examples to illustrate the points of discussion. It was seen best that the EFL teacher introduce the plan to the students and carry out the steps herself to reduce any risk to influence the participants in any way. However, the researcher attended the class sessions as students were used to having her as a visitor for the second year. The teacher first introduced the plan to the students pinpointing the benefits it may have on their scholastic achievement as well as their future academic work. She explained that the plan would take four sessions in which she would pose a question and some issues for discussion.

The students expressed some surprise in this plan but said they would participate with curiosity to see what it was. Every time the teacher started the discussion, students took time to start responding. A few were the ones who always volunteered answers. However, in each session a few more students volunteered. After each session, the researcher and the EFL teacher met and discussed the students’ response to the discussion and notes were written down.

Twice after the intervention, after one month and after two months, the EFL teacher responded to a set of questions as an assessment of the students' observed autonomy in their academic work and behavior.

Students’ responses and analysis

The following are the questions raised in the classroom, followed by the students' responses during the intervention procedure, and the EFL teacher's comments. Content analysis was used to determine the presence of certain concepts in the students’ responses to the issues raised by the teacher which are considered qualitative data.

Language awareness

The first three questions were on language awareness and took one class session.

- Think about the languages you know: English, Arabic and French- the purpose of learning languages, word formation, words in English with Arabic origin:

The students started their answers by why they learn French; for most, it was a family decision and a social requirement. They reported, we learn English ‘for fun’; it is needed to communicate on the social media; it may be a requirement for university education in Lebanon or abroad later on. This last response matched the curriculum statement which specifies that learning English as a second foreign language allows learners to follow university education through the medium of English as specified by CERD [43]. When they were asked about why they learn Arabic, a few commented, it is difficult to learn it. When redirected towards considering the purpose behind learning Arabic, a few said, it is the language of the country.

Students’ first response about why they learn languages was focused on French. This raises the question whether it is the language they are used to using most outside the classroom, or they associate themselves with it culturally! English came next in the order of the students’ responses. The purpose they identified was, besides ‘for fun’, functional or instrumental. The function that they could identify for learning Arabic was that it was their native language; this can be taken positively as it is part of their identity, but it does not reflect any other function they could identify.

Another point of discussion was whether the students were aware of the similarities and/or differences between Arabic, English and French. There was no response. The teacher tried to elicit examples of words they know in French or English that are similar and referred the students to some texts they had taken before. She got a number of responses from different students: capable, nuance, transparent, and a number of words ending with -ion: attention, information, nation, mission. Then she asked whether they could think of any words in English and French that are similar to their equivalent in Arabic. After a moment of silence, she started giving them clues and elicited the words, “when you are injured and you need to disinfect the injury, you use” alcohol; “something related to mathematics, not geometry, but” algebra; “a fruit, sour”: lemon; “something used to make tea sweet”: sugar. It was obvious that the students did not have any background information about the linguistic similarities and differences in the three languages and they could not think of examples without having a verbal prompt from their teacher or their textbooks. The teacher explained that this issue had never been raised in class before- though earlier class observations noted that she used to refer to French to guide students in learning a vocabulary word.

To build on word formation, the EFL teacher referred to the word alcohol to ask what the prefix al- refers to. She gave some words in Arabic with the prefix alsaf (the classroom) and albab (the door). A few students realized that al is the definite article attached to a noun in Arabic. The teacher used this prefix to introduce the use of prefixes and suffixes in Arabic as markers for specific meanings and elicited examples of both: alkitab (the book), kitabuhu (his book), and qalamuha (her pen). The discussion proceeded to mark the use of affixes for different meanings. Some students gave examples: akaltu (I ate), akaltum (you ate); anta (you), antuma (you two); and saathhab (I will go). The students were led to verbalize the function of these markers- possessive pronouns –hu, -ha, -tu, -tum, -ma; and for the future tense as-.

Then the teacher raised the question whether there are similar processes in French and English. Students’ reference to the use of plural -s was common and a number of examples was given in both languages- French: Maisons, students, and in English: houses, students. When focused on English, students identified the past tense marker -ed and illustrated with played, betrayed.

Word order was a point of discussion. The teacher asked how they form a sentence in English; the students showed familiarity to this concept and the answer was direct and clear: SVO, and they illustrated with examples: I bought a sandwich. We borrowed stories from the library. Claude took a chalk. Students were then asked to identify the word order in Arabic, but no answers were given. The teacher asked students to give examples of sentences and were guided to note that in Arabic word order is freer, thahabat albintu ila lmadarasa or albintu thahabat ila lmadarasa (The girl went to school); the word order of the subject and the verb is free.

- Think of the skills you have acquired, and you do well.

A minority in each of the two classes was aware of the skills they have acquired through time. Guided by the teacher’s examples, a few said that they could feel they were getting better in reading for comprehension rather than details or in reading fast; a few others thought they were becoming less subjective in class discussions and acquiring a more scientific attitude in general others reported they were getting better in process writing.

- Think of what skills you find difficult.

The students were able to identify the skills they found difficult. At first, they gave the main language category, e.g. I’m weak at grammar and writing. I can’t elaborate or illustrate with examples. I can’t speak well. I can’t express myself clearly. A few reported they find it difficult to work with others in a group or even to make friends. Doing research was another point of difficulty.

The EFL teacher later noted that with time once the students became aware of their skills, they became proud of themselves and more motivated to demonstrate their knowledge, help a peer, correct a peer’s work, etc. Moreover, the students who could identify their point of weakness could work better on overcoming their difficulties by asking for help directly from her or by referring to sources such as the internet or the reference books they have in the classroom and the school library.

Self-awareness

The second set of questions related to self-awareness.

- Think about how you can use your strengths to achieve your goals in learning.

In the class discussion, the students were guided to think of how they can do better in their scholastic achievement in any subject matter and if they use their points of strength.

Examples were given to some acquired skills or strategies, such as skimming and scanning a text before reading, and note taking while reading an assignment.

The students’ responses were limited to the teacher’s suggestions, i.e., the use of pre-reading and reading for comprehension strategies. The majority of the students found difficulty in identifying their strengths and could not relate how to use them to attain the bigger goals. The teacher elaborated on planning to achieve a task on time, setting deadlines and meet them, talking to people to share ideas, listening to others to gain insights, and being objective to succeed in results. She noted later that the majority of the students could not or did not implement the strategies that they suggested through time; it remained theoretical only!

- Identify your emotions relating to skills assessment, task complexity and executionary demand.

Students noted that they were afraid of and stressed out by tests. They also verbalized their boredom of some activities or the difficulty they face in doing them. They said out loud: This is very difficult. I don’t know what to do. Few expressed their confidence in themselves and their determination to keep focused and do better. The students’ replies are alarming; stress, difficulty and boredom can be detrimental to the students’ achievement. In constructing any curriculum such factors need to be well examined and surpassed.

- Identify what causes you stress in learning.

Many students blamed the English language itself: It’s very difficult! The teacher tried to bring to the surface other sources of stress such as lack of specific knowledge, time management, and better preparation. She later commented that if some learners do not get the point of a question from the first reading or understand a concept from the very first time, they get stressed out. This comment should serve as a corner stone to lessen the students’ negative opinion and maintain their motivation.

- Identify what causes confidence in the learning process.

The students who participated in this discussion identified the following notions: comprehension of a notion, motivation from teachers and peers, and realization that a certain task is done correctly. The teacher suggested additional points: ability to communicate, prepare, plan, ask for help, and self-evaluate, and guided the students to discuss and elaborate.

- Suggest strategies for you to beat the difficulties you face to attain goals.

The students responded to question number eight by suggesting conferencing with peers and asking a friend to help in doing the task. The EFL teacher added and held a class discussion about organizing the steps, planning the task, aiming on goal, approaching people for help. The teacher later commented that these were basic suggestions- not very creative as they were subjected to a number of strategies. This may reflect that they lacked awareness of these strategies when they were subjected to them.

- Identify any person’s motives behind taking a certain action.

To help students in thinking of motives, the EFL teacher referred to some reading and listening texts they had covered. She asked if they could identify the characters’ motive behind the behavior, and the majority of the students’ responses showed sound analysis. The responses were based on some facts in the texts: developing relations, building a career, finding a source for money, being popular, and enjoying oneself. This reveals that the students had been subjected to this kind of analysis and have acquired the skill.

- Consider your own motives to perform a task, e.g., being at school and later at the university, attaining a degree, acquiring sills such as reading or writing.

The majority of the students exhibited clear answers, such as to get good grades to pass, to get into university, to be accepted in a university abroad, to have a good career. The students’ responses again corresponded to the national curriculum’s specification that learning English as a second foreign language allows learners to follow university education through the medium of English and thus would be better prepared for future careers in the fields of trade and communication and of science and technology [42]. Moreover, the EFL teacher commented that students specially in grades 10, 11, and 12 have clearer motives as they are preparing for the French Baccalaureate, for their majors and for the universities entrance exams.

- Consider the reasons you are asked to do a task, listening, speaking, reading or writing.

Most replies showed that the reasons were not clear and that they just do it. After some attempts to elicit more focused answers, some students added that the reason may be clear in a writing task when it embodies a certain function that is clear to them or when the audience is specific. One student said that the reason is clear when they are asked to read the prompt again. This shows that students need to be told what the purpose of each activity they are required to do is. Furthermore, the responses show that the students have confidence the curriculum and the school system. This is an advantage that should be utilized to introduce the new strategies into both curricula.

- Formulate your own self-directed strategies.

Very few students had a positive response, mostly about laying out plans for their revisions prior to exams. The teacher tried to give few other examples such as setting a goal for a task, planning, setting deadline, cooperating with others, seeking help from the teacher or peers, ask for others’ opinion, and doing research.

The EFL teacher explained that the majority of the learners who could identify self-directed strategies had already set beautifully laid out plans. One can conclude that the learners in general could only see the limited short-term plan or rather the academic achievement required by the school as reflected in the grades.

Observed autonomy

To follow up the students' development of autonomy, the EFL teacher observed the students' academic work and behavior for two months and evaluated them via the following questions:

- Can your students demonstrate better capacity to take charge of their own learning?

- Can they better use effective strategies such as set appropriate learning goals, plan a task and meet deadlines, and seek their own sources to construct knowledge?

- Have they showed more positive beliefs and attitudes towards language and towards themselves as learners?

After one month, the EFL teacher reported that less than half of each of the two classes, maybe a third, showed better capacity to take charge of their learning in the sense that they tried to depend on themselves to get answers to any queries they had more than referring to her. They showed more initiative to work together in pairs or teams but were not very successful to meet deadlines in handing in edited essays. After two months, more than half of the students showed a stronger will to be more self-dependent in executing any classroom tasks and collaborated more with their peers in doing homework. The teacher reported that some students showed pride in the change they were experiencing in themselves and that they felt more mature. Some expressed their interest in what they were exposed to: This is the first time we learn about important things that we never thought of before. Maybe this will help us in the future. These students reported that they felt they were more aware of the languages they knew, their function and benefits in different areas in their life. Besides feeling the same about the students, the teacher could identify a slight change in their attitude and motivation.

To sum up the results, the intervention showed that students were intrigued by the plan and the points of discussion. It was obvious that they need time to consider, grasp and internalize self-awareness and language awareness strategies. The plan was a starting step for them to acquire the skills of needed for them to evaluate their goals, recognize their options, choose strategies, and look for sources to be autonomous.

DISCUSSION

After presenting the findings of the study and analysis, we can say that participants expressed their content in their ability to compare and contrast linguistic features in the three languages that they had been learning for years without being aware of their characteristics. A few expressed their desire to have more of these discussions that they found ‘amusing’ and ‘awakening’ to facts related to the languages. Both the EFL teacher and the researcher noted that the students could pinpoint the differences and similarities among the three languages if they are given examples of the above cases. It was obvious that they were most at ease with French, while they found English and Arabic difficult.

To answer the research question whether the introduction of self-awareness and language awareness techniques to Grade 10 EFL students can influence the development of autonomy, it is safe to say that implementing a self-awareness and language awareness plan is a starting point to open the students’ minds to skills they could acquire to promote success in their learning. Thus, the hypothesis that the EFL teacher's implementation of self-awareness and language-awareness techniques in the EFL classroom may affect the development of some Grade 10 students' autonomy in language learning is accepted provided they have time to learning and internalizing the strategies.

After the student’ direct exposure to self-awareness and language awareness, and based on their responses and the teachers’ evaluation of the intervention process, one can say that the findings of this research study are parallel to those in the related literature. The subjects’ reporting to the EFL teacher that they were more aware of what they were doing in relation to their study habits and behavior as a result of the intervention and the observation of their interest in discussing their personal and relational life reflects their concern about their image are parallel to the literature that suggested that self-awareness enriches people’s lives in several ways. In particular, the findings agree to Weisinger’s [21] report that high self-awareness enables individuals to observe and monitor their performance and Price-Mitchell’s [4] suggestion that when students become aware of their mental states, they begin to answer questions about their personal life- how to be happy, respectful, satisfied with themselves, understanding of others’ views, focused on what they should learn, and reflecting on their emotional and social lives. Furthermore, the findings of the study agree with Bourke’s [34] suggestion that when learners are actively involved in discovering language aspects and reflect on the available linguistic data and how the language works, their knowledge of the language becomes deeper. There was evidence that the participants started showing more positive attitudes towards the languages they learn, and their behavior exemplified in their queries and reports about how to handle their studies and future careers and life. The findings are also parallel to Cotterall [13] that a special language course that promotes autonomy fosters learners’ control over their language learning process and their developing language proficiency. Regarding the influence of the foreign culture as part of language learning, the students seemed not to be threatened by it, which is against Missoum’s [42] finding. Students’ first responses came in reference to French.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Following the findings in the literature as well as the study, it is recommended that self-awareness and language awareness be promoted in the various levels of the educational hierarchy. First, the Lebanese national curriculum should include the promotion of the two factors in its principles of teaching in general and English in particular. Meanwhile, schools in Lebanon take the responsibility of introducing the related strategies in the English language classes as well as all subject matters.

An explicit plan of five principles for autonomy is here suggested to design a course which is suitable for English language learners in any context. The learners:

- Analyze their personal and language learning strengths, weaknesses and needs

- Set their own goals based on their analysis of their status quo

- Construct their own plans based on the above two principles

- Choose activities and use strategies for independent language learning

- Self-assess the plans, tasks and attainment of their goals.

This plan reflects an overall approach, a systematic plan, an up-to-date methodology, a modern classroom setting, and a matching assessment policy. It entails training the teachers to a new role in guiding the learners to identify their strengths and weaknesses, to coach them to specify their goals and plan their learning path, to find the strategies and assess all the above. Teachers will be equipped with necessary resources and materials to use in the classroom. The learners have to be made aware of the main goal behind developing the new strategies that improve their proficiency in learning and performance in language use. They will also have to realize and accept their new role of self-dependence to identify their goals and plan their study accordingly.

The plan will also include practical steps for the learners to acquire the skills needed in their academic life as well as their careers and personal lives. For the plan to promote successful autonomy among the EFL learners, it needs to start at an earlier time in a student’s life to last for a longer period of time and the development of the skills has to be regularly monitored. This plan needs to take into consideration specifically the EFL context in which language learning and autonomy development are taking place. Tulasiewicz [33] warned that the absence of an explicit language awareness element from school curricula, besides aiming to teach according to specific statements of attainment, may make a direct introduction of the topic in the school syllabus rather difficult.

The plan may take into consideration a few techniques that were suggested by some researchers. Following Cotterall [13] for example, the language learning process is made relevant to guide learners understand and manage their learning in a way which contributed to their performance in specific language tasks. Moreover, according to Liu [8], learners can create simple word games to learn words they need which corresponds to role 3; they use the games to perform basic interactive routines in the TL and become fluent which relates to the first role; and their interaction with the written words begins to develop their awareness of linguistic form which is role 2.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This research was limited to a number of factors that could have affected the findings. The factors are the context, the learners’ age and grade level, and the duration of the intervention. Future research should extend to other contexts, all learners’ ages and grade levels and cover a long period of time. This could be paralleled by measuring the students’ proficiency in English and attitudes towards themselves as well as their achievement in their studies, particularly in English. Autonomy is a general concept that embodies a variety of practices that need time to develop and be demonstrated.

CONCLUSION

The study aimed at investigating the implementation of a direct plan to raise self-awareness and language awareness among learners in an EFL context to promote long term autonomy. The plan succeeded in showing initial steps to promote self-independence in some aspects of the students’ study habits and behavior. It further showed that the students became interested in how the three languages, English, Arabic and French are comparable and how they can develop, academically and personally to become better individuals. This is anticipated to guide the learners into success in language learning, careers and future life.

A curriculum should start with specific learning objectives as well as personality development goals. The implementation of any instructional plan is crucial to the success of promoting autonomy among learners. Research has to assess existing plans, modify or accept them, and construct a self-contained plan to scaffold teachers and students through the new aspects: self-awareness and language awareness. It also has to evaluate their impact on improving autonomy, language performance and attitudes towards languages.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks are due to the school which has always welcomed the introduction of new techniques, and the EFL teacher who showed willingness and enthusiasm to apply new procedures.

-

Kaur N, Malaysia M (2013) The need for autonomous vocabulary learners in the Malaysian ESL classroom. GEMA Online J Lang Stud 13(3): 7-16.

-

Holec H (1981) Autonomy and Foreign Language Learning. Pergamon Press.

-

Thaine C (2010) Teacher Training Essentials: Workshops for Professional Development. Cambridge University Press.

-

Price-Mitchell M (2015) Metacognition: Nurturing Self-Awareness in the Classroom. George Lucas Educational Foundation. Available online at: https://www.edutopia.org/blog/8-pathways-metacognition-in-classroom-marilyn-price-mitchell

-

Bilash O, Tulasiewicz W (1995) Language awareness and its place in the Canadian curriculum. In K. McLeod (Ed.) Multicultural Education. CASLT.

-

Little D (2007) Language Learner Autonomy: Some Fundamental Considerations Revisited. Innov Lang Learn Teach 1(1): 14-20.

-

Oxford R (1999) Learner Autonomy as a Central Concept of Foreign Language Learning, Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses. 38: 109-126.

-

Liu H (2015) Learner Autonomy: The Role of Motivation in Foreign Language Learning. J Lang Teach Res 6(6): 1165-1174.

-

Little D, Legenhausen L (2017) Introduction-the autonomy classroom: Procedures and principles. In Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. Language Learner Autonomy: Theory, Practice and Research. Multilingual Matters.

-

Colthorpe B (2019) Increasing Learner Autonomy. NEAS-Quality learning series. Available online at: https://neas.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/QLS-Increasing-Learner-Autonomy-PDF.pdf

-

Mariani L (1992) Language Awareness/Learning Awareness in a Communicative Approach: A key to learner independence. J TESOL- Italy 18(2): 1-10.

-

White C (1995) Autonomy and strategy use in distance foreign language learning: Research findings. System 23(2): 207-221.

-

Cotterall S (2000) Promoting learner autonomy through the curriculum: Principles for designing language courses. ELT J 54(2): 109-117.

-

Henriksen D, Cain W, Mishra P (2018) Everyone Designs: Learner Autonomy through Creative, Reflective, and Iterative Practice Mindsets. J Formative Design Learn 2(2): 69-78.

-

Dam L (2018) Learners as researchers of their own language learning: Examples from an autonomy classroom. SiSAL J 9(3): 262-279.

-

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am Psychol 55(1): 68-78.

-

Katz I, Assor A (2007) When Choice Motivates and When It Does Not. Educ Psychol Rev 19(4): 429-442.

-

Warren A (2019) Encouraging Learner Autonomy. National Geographic Learning. Available online at: https://infocus.eltngl.com/2019/11/21/enouraging-learner-autonomy/

-

Lou HC (2015) Self‐awareness-an emerging field in neurobiology. Acta Paediatr 104(2): 121-122.

-

Goleman D (2015) How Self-awareness Impacts Your Work. Penguin Random House. Available online at: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/69105/emotional-intelligence-by-daniel-goleman/9780553804911/readers-guide/

-

Weisinger H (1998) Intelligence at Work. Jossey Bass.

-

Baron RA, Byrne D (1991) Social psychology: Understanding human interaction. 6th ed. Allyn and

-

Rochat P (2003) Five levels of self-awareness as they unfold early in life. Conscious Cogn 12(4): 717-731.

-

Rochat P (2004) The emergence of self-awareness as co-awareness in early child development. In D. Zahavi, T. Grünbaum, & J. Parnas eds. Advances in consciousness research. The structure and development of self-consciousness: Interdisciplinary perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp: 1-20.

-

Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND (2010) Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6: 495-525.

-

Kamath S (2019) Cultivating Self-Awareness to Move Learning Forward. Available online at: https://www.k12dive.com/spons/cultivating-self-awareness-to-move-learning-forward/565498/

-

Premack D, Woodruff G (1978) Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci 4(4): 515-526.

-

Executive Function Skills: The Key to Academic Success. Available online at: https://www.beyondbooksmart.com/what-are-executive-function-skills

-

Carter R (2003) Language awareness. ELT J 57(1): 64-65.

-

Fairclough N (1992) Critical Language Awareness. London: Harlow.

-

Yiakoumetti L (2006) A Bidialectal Program for the Learning of Standard Modern Greek in Cyprus. Appl Linguist 27(2): 295-317.

-

Bilash O (2011) Language Awareness. Available online at: https://bestofbilash.ualberta.ca/languageawareness.html

-

Tulasiewicz W (1997) Language Awareness: A new literacy dimension in school language education. Teach Develop 1(3): 393-405.

-

Bourke MJ (2008) A rough guide to language awareness. Engl Teach Forum 1: 12-21.

-

Yang ND (1995) Effective Awareness-Raising in Language learning Strategy Training [Paper Presentation]. The 29th Annual Convention & Exposition of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Long Beach, California, USA.

-

Bull S, Ma Y (2001) Raising Learner Awareness of Language Learning Strategies in Situations of Limited Resources. Interact Learn Environ 9(2): 171-200.

-

Garcia O (2009) Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Knowledge about Language. Springer. 6: 385-400.

-

Hurd S (2005) Distance education and languages. Multiling Matters, pp: 1-19.

-

Farahian M, Rezaee M (2015) Language Awareness in EFL Context: An Overview. I J Lang Liter Cult 2(2): 19-21.

-

Palfreyman D (2006) Social Context and Resources for Language Learning. System 34(3): 352-370.

-

Palfreyman D (2003) Introduction: Culture and Learner Autonomy. In D. Palfreyman, & R.C. Smith eds. Learner Autonomy Across Cultures. Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Missoum M (2016) Culture and Learner Autonomy. J Faculty University of Blida2, Algeria, pp: 57-92.

-

Centre for Educational Research and Development (1998) English as a Second Foreign Language. Republic of Lebanon. Curriculum. Curricula of 1997 Creed 10227/97.

-

United Nations (1997) Model United Nations. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/mun

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- International Journal of Internal Medicine and Geriatrics (ISSN: 2689-7687)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- International Journal of Medical and Clinical Imaging (ISSN:2573-1084)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- Journal of Carcinogenesis and Mutagenesis Research (ISSN: 2643-0541)

- Chemotherapy Research Journal (ISSN:2642-0236)