3934

Views & Citations2934

Likes & Shares

The purpose of this sabbatical and study was to allow me the opportunity to create art [1,2], be in the creative process [3-5], build on my identity as an artist [1,2], and use Jung’s processes of active imagination and dream journaling to better know myself on my path of individuation [6]. The emphasis was on the practical experience of creative self-expression through painting, process or product, to explore painting for soul connection and my artist’s identity. I used a mixed method phenomenological heuristic methodology to describe my lived experience of intuitive creativity to explore painting for soul connection and my artist’s identity. To do this, I used process and product painting over a 9-month sabbatical experience. To validate the qualitative results, I triangulated the data with measuring changes in anxiety, depression, self-esteem, and creativity.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Process painting is defined as painting from the source, with no plan or direction [3,7]. Process painting involves responding intuitively with no judgment to the materials, with no end product in mind [3,7]. Painting from the source is therapy and art [3].

Miller [8] utilizes process painting in art therapy supervision based on Cassou and Cubley’s [7] intuitive painting approach. Miller [8] calls her process the el duende one-canvas process painting experiential, a mysterious force manifesting as creativity. This art-based supervision experience involves five-phases: an experiential invocation, weekly depth process painting, photographing the process, reflective journaling, and a culminating project [8,9].

In the el duende process, the canvas becomes a metaphor for the developing self [9]. When the authentic expression of the supervisee is present in the artwork, the “soul’s voice” of the supervisee appears (p. 16). Robb and Miller [10] note that supervisee disclosure is visible in the artwork before conscious awareness by the supervisee. By intuitively painting, the unknown unconscious material becomes conscious [9]. By making the unconscious, conscious, a tension of the opposites can occur to evoke new learning. Jung [11] calls this process the transcendent function. Process painting is an example of what Jung [6,11] calls active imagination or an enactment technique [12] to engage the transcendent function. An enactment technique uses an unstructured situation or material, e.g. paint, for direct interaction with the unconscious while one is awake in response to a dream or an image [12]. I am drawn to the use of creative media, e.g. painting, to explore my own unconscious and the use of my nightly dreams to guide my way in this creative process [6,11,13].

Wallas defined the creative process in four stages: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification [5]. The Second stage involves unconscious processes. Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of the unconscious in creative thinking describes what occurs in this stage [5,14]. His theory expands on psychoanalytical theory [5]. In this incubation stage, there is an interaction between the conscious and unconscious minds, where the unconscious has the ability to work on many problems at once in a parallel process mode [5,14]. Insights result as ideas produced in the unconscious become conscious [5,14]. More recent investigations in neuroscience support empirical evidence that the process of insight is a complex whole brain activity involving interconnections between the right and left hemispheres as well as the front and back lobes [15-17]. Csikszentmihalyi’s research in the 1990’s supports people’s need to structure solitary idle time followed by intense work to create space for insights, like on vacations or sabbatical [5]. Theoretical approaches to creativity are traditionally defined in terms of process, product, person, and place [4]. “Creativity tends to flourish where there are opportunities for exploration and independent work” [4]. My sabbatical provided the opportunity to be in unique places for me to explore my creative process and investigate my experience in terms of process and product.

In addition, Moon [1] advocated that the art therapist develops the artist within in order to be a more compassionate therapist. Moon [1] recommends dedication to acquiring knowledge, immersion in the arts, and attention to self-study. For this study, this dedication involved support and stimulation in various workshops, individual sessions, and immersion into the art world of New Mexico, New York City, and Italy.

Creative blocks were addressed, challenged, and explored in both the painting and a daily reflective journaling [18]. To explore my depths of my psyche, access is gained through art’s depiction of dreams, imagery, and the imagination [18]. The soul is awakened or liberated with each artwork [19,20].

To approach this study of my creative process painting for soul connection and artist’s identity, a convergent parallel mixed method approach was utilized combining the heuristic model of qualitative inquiry and quantitative validated questionnaires [21] to answer the research question. Mixed methods provide open ended and closed ended data to complement the research question [21,22]. The qualitative and quantitative data were collected, analyzed separately, and compared to confirm or not confirm each other [21]. Long [22] identified that there is a dearth of mixed method studies on creativity published in the last 15 years. Less than 5% (n = 22) of the 612 empirical studies on creativity were mixed methods. Mixed method studies have been identified as areas of interest to advance the field of art therapy [23].

The heuristic model requires the researcher to delve into the phenomena under exploration because it has personal meaning [24,25]. As a result, the researcher has the opportunity for growth in self-knowledge and self-awareness [25]. Moustakas’ [26] study on loneliness is a classic heuristic study. He explored his own feelings of loneliness. Then he explored the feeling in other people. Fenner [27] applied the methodology to her exploration of creating brief drawings over a two-month period to enhance personal meaning and change. Cole [28] utilized the heuristic methodology to explore her experience of time and its significance in therapy.

I used a convergent parallel mixed method approach that included the phenomenological heuristic methodology to answer the research question: what is my lived experience of intuitive creativity to explore painting for soul connection and my artist’s identity over a 9-month sabbatical experience? To validate the qualitative results of this lived experience and add depth related to my creative process and emotional experience, I triangulated the data with measuring changes in anxiety, depression, self-esteem and creativity. The quantitative questions explored the change in depression, state and trait anxiety, self-esteem, and creativity over the same time period.

METHODS

Research Design

This convergent parallel mixed method approach utilized the heuristic self-study design [25] and quantitative validated questionnaires [21]. The heuristic self-study design based on Moustakas’ [25] is a six-stage model combined with quantitative self-report measures for anxiety, depression, self-esteem, and creativity for one participant. Moustakas’ [25] six stages are initial engagement, immersion, incubation, illumination, explication, and creative synthesis.

The qualitative question is: What is the lived experience of intuitive creativity to explore painting for soul connection and my artists identify? The quantitative question is: How does anxiety, depression, self-esteem and creativity change over the period of the sabbatical related to my lived experience with creativity? I hypothesized that State Anxiety and depression would diminish; Trait Anxiety would remain the same; and self-esteem and creativity would increase.

Instrumentation

The standard assessment tools used are: State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) [29], Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI) [29], Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) [30], Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) [31], and the Barron-Welsh Art-Scale (BWAS and BWAS Revised) [32]. The state anxiety inventory (SAI) measures a person’s response to anxiety at any given moment or situation [29]. The trait anxiety inventory (TAI) measures the relatively stable individual differences in how people perceive anxiety. Trait anxiety is expected to remain constant, whereas state anxiety is situation dependent and expected to vary over time. The two scales range from 20 to 80 where the higher the number on the scale, the greater the anxiety.

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) reflects a degree of depression, not a diagnosis of depression [30]. The scores range from 0 to 63, where 0 to 13 indicates minimal depression, 14 to 19 indicates mild depression, 20 to 28 indicates moderate depression, and 29 to 63 indicates severe depression.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) is a measure of self-esteem [31]. The scale ranges from 0 to 30. Scores between 15 and 25 are within the normal range. Scores below 15 suggest low self-esteem.

The Barron-Welsh Art-Scale (BWAS) and its revised scale [32] measure creativity. The scales range from 0 to 60 where the higher the scale on each, the more creative the person.

Procedure

The procedure involved Moustakas’ first two stages of initial engagement and immersion for 303 days of the sabbatical. These stages involved focused opportunities to paint and be immersed in art in private studios, workshops, and museums. The artwork was documented with photographs. Private studio painting was in the northeast and the southwest. Workshops were in New Mexico and Texas. Museum experiences were in New Mexico, New York, and Italy. Following the sabbatical, the experience was summarized in written format using the qualitative questions. The qualitative data included the artwork created, daily journal entries, and the written summary.

The quantitative instruments were measured at the beginning (August), middle (December), and the end (June) of the sabbatical experience. The quantitative data also included the descriptive data that supports the lived experience. The descriptive data is: number of paintings produced, number of hours painting, number of journal entries, dream entries, meditations, and exercise routines over time.

Validity/Credibility

For heuristic phenomenological studies, qualitative validity is defined in terms of trustworthiness, authenticity, and credibility [21]. To enhance the validity of the qualitative data, the data was triangulated with the quantitative data and the literature, the results used rich, descriptive language in the final narrative, and the researcher’s bias is noted in the limitations [21]. For the quantitative instruments used, each assessment tool has documented validity and reliability [29-32]. Snir and Regev [33] argue that self-report assessment tools with documented validity and reliability add value to art therapy research.

Data Analysis

The data analysis occurred after the sabbatical experience. The qualitative data analysis involved Moustakas’ incubation and illumination stages. In these stages, the qualitative data was organized, read and reread, and coded for themes. Moustakas’ final stages, explication and creative synthesis, complete the process. The result is a rich, descriptive narrative, which answers the qualitative research questions. The quantitative assessment data was calculated after the 9-month experience, except for the BWAS, which was calculated by the on-line program via www.mindgarden.com when the assessment was taken [32]. However, the results were not analyzed until the 9-month experience ended.

RESULTS

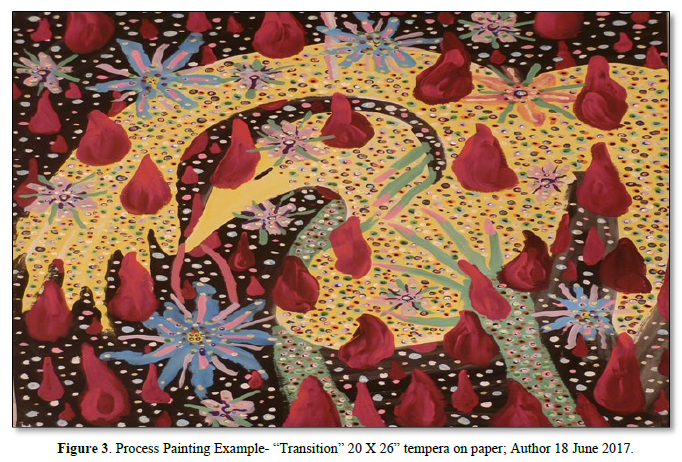

Table 1 summarizes the sabbatical descriptive data. Figure 1 summarizes the descriptive data in a bar graph depicting the number of hours painting, number of journal entries, dream entries, meditations and exercise routines over time. I created the following artworks: 37 process paintings-tempera and watercolors (examples in Figures 2 & 3), 47 product paintings-watercolors (examples in Figures 4-6), and 4 others-2 mandalas and 2 collages. Over the 303 days, I produced: 0.28 artworks per day (2 artworks per week). I painted an average of 1 hour per day (7h per week). I wrote in a journal daily and I wrote 255 journal entries and 256 dream entries. I produced an average of 1 journal or dream entry per day and an average of 6 journal or dream entries per week.

The assessment results are:

- The SAI was 60, 20, and 29, respectively

- The TAI results were 27, 40, and 21, respectively

- The BDI-II results were 17, 7, and 0, respectively

- The RSE results were 29, 26, and 30, respectively

- The BWAS results were 32, 38, and 45, respectively

- The BWAS Revised results were 37, 48, and 50, respectively.

The BWAS scales are normalized for gender and creative expression.

Qualitative Results-The Narrative Experience

The Journey

The journey began with a road trip to Taos, NM in August 2016. For eight weeks, I rented a 900 square foot artist’s studio. The studio’s doors looked out onto Taos Mountain. At week four I participated in a process painting workshop.

The driving journey from Taos towards home began at the end of October via Texas so I could attend another process painting workshop. I arrived home in the northeast the week before Thanksgiving. I had been on the road for 12 weeks. For the spring, I also traveled to various process painting workshops, but I did not stay away for an extended period of time.

Both at home and in the Taos studio, I had space for the process painting. The tempera paints were set up to my right to be easily accessible and inviting. I had multiple large white tables set up separately for my watercolors, also accessible.

Process Painting

In both the studio spaces, I explored the question: How do I experience the process painting on my own? I set up the white paper on the easel. I had a variety of brushes available, an assortment of colors of tempera paint, and water ready for cleaning.

Process painting involves no planning or long-term decision, only in-the-moment decisions. What color am I drawn to? Red? Blue? Yellow? How do I make a mark on the paper? A line? A dot? A figure? Do I have an image in mind? How do I start with that image? I do not fill the paper, I leave the pregnant white void as long as possible. I never know what may come days from when I begin in a corner of the void. I may paint big broad strokes. I may paint tiny dots.

Often when I wonder what to paint next, I look at the colors. I may be drawn to light blue, I look at the paper. There seems to be a glowing space on the paper where I need to put that dot. I know that is where the next bit of paint needs to go. I keep the brush moving. I may get a sense of the next image and I paint it.

If I am feeling stuck, I may refer to Cassou’s [34] book of Questions to stir my process. Questions that I found helpful are: “If I could paint what I thought was the ugliest, the most disgusting, or the sweetest sugary picture what would I paint? Then why don’t I paint it?” I gave myself permission that anything goes and I did not have to show the pictures to anyone. I trusted my higher Self, especially when I really wanted to resist. What I truly did not want to paint, needed to be painted.

Being in the group for process painting workshops allowed me to answer the question regarding my experiences in groups. The structured workshop helped me with more focused time and discipline on painting. I was not so easily distracted by the need to go to the grocery store, do laundry, or make dinner. I painted longer days and bigger pictures. If I really hated the painting, I simply needed to keep on painting. It was amazing how many paintings I detested and yet came to love.

I painted 37 process paintings of various sizes typically ranging from 19 X 25” to as big as 52 X 76”. Figure 2 is a process painting depicted at the beginning of the sabbatical, titled “White bugs taking hold” (18 X 24”, 26 September 2016). In Figure 3, the final process painting is titled, “Transition” (20 X 26”, 18 June 2017).

Product Painting

For product painting I focused on watercolors. I need to plan a product painting. The watercolor media also requires planning because of the technique. If not done right, the watercolor paints would blend and flow into one another creating “mud.”

I was inspired to paint watercolors in the fall when the fall foliage took hold of the Taos landscape. The colors of the sky, the trees, the adobe, and the desert were breathtaking and awe inspiring. I could not get enough of the contrast of the yellow of the changing leaves and the turquoise blue sky (Figure 4). I would paint yellow bursts of trees changing colors, setting suns across desert landscapes, and desert canyons (Figure 5). I painted 47 watercolors. Figures 4-6 depict those watercolors.

Journaling and Dreams

Over the course of the sabbatical I journaled daily. I started each day’s entry with the dream content. Then I wrote my daily discourse. I use stream-of-consciousness writing. The daily journaling allowed me the space to process life events, e.g., death of my mother-in-law, national presidential election, and cancer diagnosis and treatment. I explored feelings, emotions, and experiences. For example, on 9/24/16 as I started the first process painting workshop, I journaled, “The dream is dark. It’s chaos. I am searching. I am wondering what to do next. I go into the dark room. I am in a large place, a castle. I’ve been here before. Everyone tells me what to do. I am tired of everyone telling me what to do.” I was focused on facing the void of the empty sheet of paper to paint while being part of the group experience. I was afraid.

Life events

Numerous life events impacted me during this experience. In the fall while in Taos, my mother-in-law died. My husband and I met up for her funeral. Having the studio space in Taos to return to provided me time and solitude to process this loss. I painted.

The emotional impact on me of the national presidential election surprised me. I was downright depressed when the Republican candidate won. I was alone in Texas at that time. How could I process this? I continued to journal and paint. For example, on 11/10/16, after the election, while I spontaneously painted a “rat,” I dreamt the following:

The dream is dark and full of chaos. I keep repeating a trip down a class III rapid around a blind corner at the end. As I pass the blind corner I tell myself, “The first time I did this part of the rapid, I was a kid and it was an accident.” I paddle more and more of the rapid from further upstream. I do it again and again. I paddle and then swim out again and again. Also, a big herd of elephants come around again and again. The elephants are familiar with me as I am with them. I wander through the herd with no problem. I notice that on this particular day, the elephants’ skin is thicker, layered in an almost scaly fashion, and droopy. I return to the rapids and run them again. I’m not afraid of the elephants. I seem relieved by that.

When I returned home in November, I followed up on my annual gynecological exam, including my annual mammogram. I was notified to return for a follow-up mammogram. I had the following dream (1/16/17) depicted in Figure 6.

The dream is full of chaos. The house has all sorts of boulders scattered on the roof. I stand by the front door entrance. A boulder comes roaring, rolling towards me. This boulder is the size of a small car. It stops to rest by the front door, just missing me. “Oh My God! A bolder almost crushed me!” I cry. I rush further inside the house for cover, but am I really safe? The booming noise still bounces and moves boulders on the roof. “What the hell is going on here?” I wonder.

In the follow-up in January, I was informed I had breast cancer. My first response came from a place of denial. I quickly understood that this diagnosis was serious. Cancer kills people. My health was my first priority. Shock is also a stage experienced when learning about this diagnosis. One reason is that I have always and still do feel great. I may have had a cancer diagnosis, but I was not ill. The cancer was stage one, the most common stage. After three surgeries, I am cancer free. The next phases of treatment continued as I continued to journal and paint.

Ah-hah’s and Insights

I experienced ah-hah moments and insights that lead to inspirations. These inspirations relate to my experience painting, my need to purge and paint, relationships, meditation, exercise, and the need for balance. For example, in the fall, I wondered, “does this loss of my mother-in-law also contribute to my inspirations?” I painted. When I returned to home after 12 weeks on the road, all I wanted to do was purge and paint. The purging took the form of compulsive intense sorting, shredding, tossing, donating, and recycling. Then I discovered I had cancer. Symbolically, this diagnosis fits with my compulsion to purge, sort, shred, toss, and donate. The cancer literally had to be “cut out” of me with surgery.

Being away from my husband for the most part of 12 weeks in the fall helped me to realize that I did not want to be away from my husband for 12 weeks. I realized a level of depth and love regarding my feelings for my husband. In addition, to celebrating the importance of our relationship and work on my sabbatical agenda, we traveled to Italy in the spring for our 25th wedding anniversary. In Italy, we immersed ourselves in art.

I also had the realization that I needed to balance my need to paint, to be in a relationship, to be spiritual and meditate, and to be healthy by eating well and exercising. My meditation and exercise routine started more regularly in December when I returned home (Table 1 & Figure 1). I made a point to hike 2.7 miles the day before each surgery, as well as the day following surgery.

DISCUSSION

In this mixed method research study, the qualitative question was: What is the lived experience of intuitive creativity to explore painting for soul connection and my artists identify? The qualitative themes describe this lived experience painting with the journey into the experience, continued with process and product painting, enumerated the role of journaling and dreams, elucidated life events, and concluded with ah-hah moments. To connect with my soul and my artist’s identity, the experience takes me into the actual activity of painting, whether it is painting for process or painting for product. I created 37 process paintings to connect with my intuitive self for soul connection. I created 47 product paintings using watercolors to connect with my public persona as an artist. The acts of daily journaling and dream recording are highlighted to touch on the idea of how I use these to explore soul connection and my sacred shadow.

Life continued on as I took this sabbatical break. I worked through major life events of death, politics, and cancer. For example, the process painting helped me as I worked through the cancer diagnosis, three surgeries, and preparation for radiation treatment. This creative process also inspired me to new actions or renewed vigor. To deal with this health event, I was inspired to exercise and meditate. I was therefore able to regulate my emotions, my anxiety, and my depression as my emotions went on a roller coaster ride dealing with cancer. I was able to maintain a healthy self-esteem. I was able to continue being creative and paint more and connect with myself, my soul.

I had some ah-hah moments. These moments bubbled up to consciousness from the unconscious in moments of scheduled solitary time journaling or hiking followed by work with painting like respondents reported in Csikszentmihalyi’s studies [5,14]. As I painted, journaled, exercised, then paused, I discovered a new depth of love for my husband and my need to not be far away for extended periods of times. I connected to my life and found new meaning in my own existence. I connected to my soul.

The lived experience of painting supported both my soul connection and my artist’s identity, whether I painted for process or product. Moon [1] argues that the purely spontaneous expression has no place in the world of art therapy. I disagree. My experience of facing the void of the white paper, the flow of the paint, the images that were birthed are grounded in the theoretical foundation of Jung’s concept of making the unconscious, conscious and further supported by Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of the unconscious in creative thinking [5,14]. It is this spontaneous expression with the tempera paint, without the critical voice of my conscious mind, that connects me more and more to the language of my unconscious mind. It is nightly dreams that Jung recommends one to connect to in order to unearth one’s unconscious, one’s shadow in order to grow to be more whole, more connected with the Self [13]. This spontaneous expression is my link to my soul. Chilton [35] notes that neurologically, “the execution of artistic behavior provides access to information that the brain retains but which cannot come to consciousness any other way” (p. 66). For example, Robb and Miller [10] note that supervisee disclosure is visible in the artwork before conscious awareness by the supervisee when the using el duende process painting. In this process, the evidence of my illness appeared in my dream (Figure 6) as well as in the painting in the form of the “white bugs taking hold” the 26th September 2016 (Figure 2) long before the diagnosis in January 2017.

I recalled my dreams daily and I journaled them. My dreams relate to the painting process in that both processes are stream-of-consciousness experiences. I have found that by simply writing down the dream content, or even painting it, I am often aided with understanding and insight. At other times these acts simply result in a feeling of being grounded and connecting to myself. These acts are what Jung calls tools of active imagination [6,11]. Thus, my act of dream journaling, and occasionally painting them, was an act of soul connection for me, a way to connect with my shadow, unconscious material [6]. These acts were part of the creative stage of incubation, a stage where unconscious processes occur for insight formation to bubble to consciousness [5,14]. Paying attention to my dreams daily aided me in working through the sadness and grief on the fall trip to my mother-in-law’s funeral, my angst and depression regarding the national presidential election, and my shock and denial of my cancer diagnosis. I journaled then I painted. And I painted then journaled more. My dreams are an important part of my lived experience of intuitive creativity using painting for my soul connection of making my unconscious conscious.

To cultivate my artist’s identity, I approached my sabbatical in a systematic, disciplined way to allow for the creation of art as Moon [1] recommends. I designed the project in response to Allen’s [2] concerns about the experience of the art therapist’s “clinification” as we develop our professional roles as art therapists. I needed the opportunity to create art, immerse myself in art, in nature and in the beauty of the world. From a product painting perspective, I was inspired by the fall Taos landscape and I painted watercolor after watercolor. From a process painting perspective, I needed to paint to process difficulties in my life, e.g. death, illness, and politics. I painted and painted. I journaled and meditated. I responded and painted more.

I experience process versus product painting differently, as evidenced by the pieces in Figures 2-5. These differences can be explained by the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) [36]. My approach to process painting is from the “bottoms-up” direction according to the ETC. Creative synthesis has been achieved in the process paintings in Figures 2 & 3. Process painting is a kinesthetic/sensory experience. Whereas, in referring to the watercolors in Figures 4 & 5 these examples of my product paintings are from the “tops-down” direction of the ETC. Creative synthesis has been achieved for these watercolors. My product painting is primarily a cognitive/symbolic experience. In both instances of process and product painting, I have been able to experience the flow, which is linked to my creative expression and well-being [35]. The description of my experience in both process and product painting support my creative expression and my artistic identity. I need both process and product painting to be truly connected to my Self.

Then at the end, I took a clinical view of the standard assessment data for anxiety, depression, self-esteem and a creativity measure to see if I did indeed change over time while being immersed in this creative process. In addition to exploring my creativity, my lived experience involved dealing with life events of death, politics, and illness. Having emotional fluctuations of anxiety, depression, and self-esteem would be normal under these circumstances, and one could speculate they might influence my experience with my creativity.

The quantitative question was: How does anxiety, depression, self-esteem and creativity change over the period of the sabbatical related to my lived experience with creativity? I hypothesized that State Anxiety and depression would diminish; Trait Anxiety would remain the same; and self-esteem and creativity would increase. The quantitative data supports my improved well-being albeit I was dealing with death, politics, and cancer. For example, I hypothesized that the SAI and the BDI-II would diminish and it did. When my sabbatical commenced, I exited a full-time work experience preparing for coverage of my sabbatical. My anxiety and depression were high. I suspected disengaging from the work responsibilities and focusing on the creative expression of process painting helped me to be less anxious and depressed. The fact that the SAI subsequently increased slightly is not surprising as I was also dealing with my cancer diagnosis and treatment. My TAI results had an average value of 29. Whereas, the RSE results support that my self-esteem remained stable over the time period. The RSE results were within the normal range of self-esteem with an average of 28 [31].

My creative expression as measured by the BWAS and BWAS revised supports that it increased as hypothesized. The BWAS results of 32 and higher relate to creative individuals like art institute students, playwrights, and architectural firm employees [32]. Similarly, the BWAS Revised results of 37 and higher correspond to creative individuals like playwrights [32].

This specific quantitative result supports my qualitative question. I was able to improve my creativity being immersed in my creative process, be it product or process, for soul connection and my artist’s identity over this sabbatical period.

LIMITATIONS

There are many limitations in this study. The major limitation is this study focuses on the subjective experience of one person. Both the qualitative and quantitative results are therefore biased. Self-report tools reflect the person reporting [33]. Although a third party on-line calculated the BWAS results, I calculated the other quantitative results. The results cannot be generalized to other populations.

IMPLICATIONS

The design of this mixed methods study allows for its replication. Combining the exploration of the phenomena of intuitive creativity in painting for soul connection and artist’s identity, immersion into painting, be it for process or product, journaling daily and paying attention to dreams, coupled with measuring changes in anxiety, depressions, self-esteem and creativity allow for further avenues of research for other art therapists. The study allowed for the exploration of process versus product painting; how these two avenues of approaching the application of art therapy, process versus product painting, could be further explored as phenomena by art therapist and/or client. Are they different experiences? How can the ETC explain each experience? In addition, new research questions that emerged in the process of this analysis. The new research questions are: (a) what archetypes reveal themselves in the paintings and the dream data? And (b) Are there any archetypes present in the paintings and the dream data that suggest a relationship to the life events that occurred during this time period, i.e. death, political strife, or cancer?

CONCLUSION

I described the lived experience of intuitive creativity using painting for soul connection and my artist’s identity over a 9-month period. My soul connection requires painting, dreaming, and journaling. As a result, I have a change in perspective on life. As a human being, I need to create art regularly, whether it be for process or product. Jung’s process of active imagination is useful to better know myself. Creating art is helping me conquer my cancer diagnosis. I trust that my intuition knows what I need to paint for my soul connection. My mantra is “I’m alive and I feel great!” I recommend painting, dreaming, and journaling for all.

- Moon CH (2002) Studio art therapy: Cultivating the artist identity in the art therapist. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Allen PB (1992) Artist-in-Residence: An Alternative to “Clinification” for Art Therapists. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 9(1): 22-29.

- Gold A (1998) Painting from the source. New York: Harper Collins Books.

- Kozbelt A, Beghetto RA, Runco MA (2010) Theories of creativity. In J.C. Kaufman & R.J. Sternberg, (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp: 20-47.

- Weisberg RW (2006) Creativity: Understanding innovation in problem solving, science, invention, and the arts. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jung CG (1990) Dreams. Vol: 4,8,12,16. In G. Adler, M. Fordham, W. McGuire, & H. Read, (Eds.); Hull, R.F.C., Trans., The collected works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, New Jersey: Bolligen Series XX Princeton University Press.

- Cassou M, Cubley S (1995) Life, paint and passion-reclaiming the magic of spontaneous expression. New York: Jeremy Tarcher/Putman Book.

- Miller A (2012) Inspired by El Duende: One-canvas process painting in art therapy supervision. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 29(4): 166-173.

- Miller A, Robb M (2017) Transformative phases in el duende process painting art-based supervision. Art Psychother 54: 15-27.

- Robb M, Miller A (2017) Supervisee art-based disclosure in El Duende process painting. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 34(4): 192-200.

- Jung CG (1977) Two essays on analytical psychology. Vol: 7. In G. Adler, M. Fordham, W. McGuire, & H. Read, (Eds.); Hull, R.F.C., Trans., The collected works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, New Jersey: Bolligen Series XX Princeton University Press.

- Hall JA (1986) The Jungian experience: Analysis and individuation. Toronto, Canada: Inner City Books.

- Jung CG (1989) Memories, dreams, and reflections. (R. and C. Winston, Trans.). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Csikszentmihalyi M (1996) Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins.

- Corballis MC (2018) Laterality and creativity: A false trail? In. R. E. Jung & V. Oshin (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the neuroscience of creativity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp: 50-57.

- Fiore SM, Schooler JW (1998) Right hemisphere contributions to creative problem solving: Converging evidence for divergent thinking. In M. Beeman & C. Chiarello (Eds.), Right hemisphere language comprehension: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erbaum Associates. pp: 349-371.

- Salvi C, Bricolo E, Kounios J, Bowden E, Beeman M (2016) Insight solutions are correct more often than analytic solutions. Think Reason 22(4): 443-460.

- McNiff S (1992) Art as medicine. Creating a therapy of the imagination. Boston: Shambala.

- Learmonth M, Huckvale K (2008) Art psychotherapy: The wood in between the worlds. New Ther 53: 11-19.

- McNiff S (1989) Depth psychology of art. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, Publisher.

- Creswell JW (2014) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Long H (2014) An empirical review of research methodologies and methods in creative studies (2003-2012). Creat Res J 26(4): 427-438.

- Kaiser D, Deaver S (2013) Establishing a research agenda for art therapy: A Delphi study. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 30(3): 114-121.

- Bloomgarden J, Netzer D (1998) Validating art therapists’ tacit knowing: The heuristic experience. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 15(1): 51-54.

- Moustakas C (1994) Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Moustakas C (1961) Loneliness. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Fenner P (1996) Heuristic research study: Self-therapy using the brief image-making experience. Art Psychother 23(1): 37-51.

- Cole A (2014) ‘Being time’: An exploration of personal experiences of time and implications for art psychotherapy practice. Int J Art Ther 19(2): 71-81.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) STAI manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) BDI-II: Depression Inventory II-Second Edition: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.

- Rosenberg M (1979) Conceiving the self. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Welsh GS, Gough HB, Hall WB, Bradley P (2003) Barron-Welsh Art-Scale: Manual and sampler set. Available online at: www.mindgarden.com

- Snir S, Regev D (2014) Expanding art therapy process research through self-report questionnaires. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 31(3): 133-136.

- Cassou M (2004) Questions: To awaken your creative power to the fullest. San Rafael, CA: Michele Cassou.

- Chilton G (2013) Art therapy and flow: A review of the literature and applications. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 30(2): 64-70.

- Lusebrink VB (2010) Assessment and therapeutic application of the Expressive Therapies Continuum: Implications for brain structures and functions. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc 27(4): 168-177.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Carcinogenesis and Mutagenesis Research (ISSN: 2643-0541)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- International Journal of Diabetes (ISSN: 2644-3031)

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

- Journal of Allergy Research (ISSN:2642-326X)

- International Journal of Radiography Imaging & Radiation Therapy (ISSN:2642-0392)

- Journal of Pathology and Toxicology Research