Research Article

Coping Strategies and Disposition towards Gratitude among Type-A Personality: An Exploratory Study among Clinical Psychologists and Counselors

149950

Views & Citations148950

Likes & Shares

Mental health professionals work under a great deal of stress. Although the occupational-stress literature in general is vast, there are a few studies of stress among psychotherapists. The purpose of the current research was to study whether Type-A personality differs from Type-B personality in their use of coping strategies, the disposition of Type A/B people towards gratitude as well as to study the relationship between gratitude and coping in a sample of psychologists and counsellors. Type-A personality, Disposition towards gratitude and Coping strategies were measured using the Framingham Type A Scale (Haynes et al., 1978), the Gratitude Questionnaire (McCollough, Emmons & Tsang, 2002) and the Ways of Coping Scale (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988) in 54 professional counsellors and/or psychologists (45 females) meeting the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the participants was 33 years with standard deviation of 9.01. Data analysis included t test and spearman’s correlation. No significant difference was found between Type A and Type B psychologists and counsellors concerning coping strategies. However, Type A individuals were found to use AR, EA, and EF coping strategies more than Type B individuals. A strong correlation was found between disposition towards gratitude and coping. Results are discussed along with strengths and limitations of the study and some future recommendation.

Keywords: Personality, Type A, Disposition towards gratitude, Coping

Abbreviations: PF: Problem-Focused; EF: Emotion-Focused; G: Disposition Towards Gratitude

INTRODUCTION

Today, the nature of a clinician’s job has become more complex and demanding than before. There can be business-related, client-related, setting-related, personal challenges of therapy and evaluation-related stressors for a therapist [1]. A substantial literature testifies to the potential negative effects of therapy work on therapists. However, less is known about the potential positive effects and aspects of being a therapist. The therapeutic training and practicing orientation of the therapist can also contribute to their growth and wellbeing. The present study is an attempt to refocus and rekindle the interest and curiosity in the positive aspects of being a therapist.

TYPE A AND TYPE B PERSONALITY

American Psychological Association [2] defines personality as “individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving,” thereby emphasizing an individual’s uniqueness and adopting an idiographic view. However, Eysenck views types as the general dimensions around which personality is organized [3]. Friedman and Rosenman described two personality types A and B. ‘Type A’ refers to an ‘overall style of behavior’ that is observed in persons who are excessively time conscious, competitive, ambitious, hard-driving, and confident [4]. Cooper et al. [5] characterized the ways in which Type A individuals respond as aggressive, achievement oriented, dynamic and hard driving, assertive, fast paced (in eating, walking and talking), impatient, competitive, ambitious, irritated, angry, hostile and under time pressures. Dembroski [6] described Type B individuals as generally relaxed, calm, quiet, attentive, and mellow. They are open to criticism and try to make others feel accepted and relaxed.

COPING

Broadly, coping has been defined as “any effort at stress management” [7]. Coping mechanisms include individual’s attempt to directly alter the threatening condition, to change their appraisal of stressors as less threatening, and/or to regulate stressful emotions.

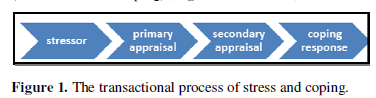

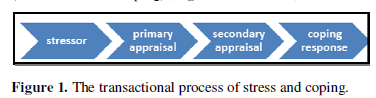

The cognitive theory of psychological stress and coping by Folkman and Lazarus [7-9] views the process as transactional wherein the person and the environment are in a dynamic, mutually reciprocal, relationship [10].

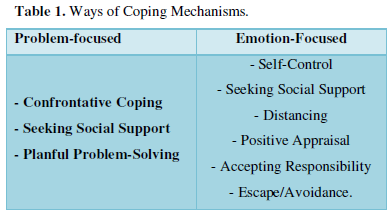

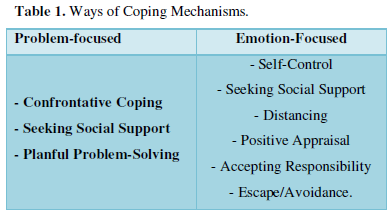

Generally, coping strategies have been divided into two categories, i.e., problem-focused (PF) or emotion-focused (EF). According to Lazarus and Folkman, problem-solving strategies are efforts to do something active to alleviate stressful circumstances, whereas emotion-focused coping strategies involve efforts to regulate the emotional consequences of stressful or potentially stressful events. Therefore, researchers conclude that coping has two major functions: dealing with the problem that is causing the distress (problem-focused coping) and regulating emotions (emotion-focused coping) (Figure 1 & Table 1).

Research indicates that people use both types of strategies to combat most stressful events. These two coping types can be seen as complementary coping functions rather than independent coping categories. Personal style and the type of stressful event, both influence the type of strategy used [11]. The present study is primarily concerned with the use of problem-and emotion-focused coping as theorized by Lazarus and Folkman.

Disposition towards Gratitude

Most people experience the emotion of gratitude frequently and strongly. As a psychological state, gratitude is a felt sense of wonder, thankfulness, and appreciation for life [12], experienced by more than 90% of adults. According to Emmons and McCullough [13], gratitude stems from the recognition of a positive outcome as being generated by another individual who behaved in way that was (1) intentionally rendered, (2) costly to him/her and (3) valuable to the recipient.

Gratitude, like other affects, could exist as an affective trait, a mood, or an emotion. It has been conceptualized in two ways: dispositional (i.e., trait) gratitude and state gratitude [14]. Dispositional gratitude is the tendency or proneness to experience gratitude, which might be called a personality trait. It is a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains. There are four facets of grateful disposition: intensity, frequency, span, and density. These elements are referred to as facets because they are believed to co-occur [15]. Conversely, state gratitude is the momentary experience of the emotion of gratitude when one realizes that something good has happened because of some other person or force [16].

LITERATURE REVIEW

A comprehensive literature review provided an understanding of the existing patterns and relationships among these variables.

Coping and Personality

Several empirical studies have demonstrated significant associations between personality variables and coping responses. For instance, internal locus of control is associated with greater use of active, problem-focused strategies [17-19]. High extraversion and low neuroticism predict the use of coping strategies judged as more effective [20]. Similarly, Type A individuals report greater use of active coping, planning, and suppression of other activities than Type Bs [18,21]. Cognitive theorists propose that individuals with a high score on personality traits, such as neuroticism [22], and characteristics of Type-A personality [23] utilize ineffective coping strategies, which in turn lead to higher levels of distress. Investigating more complex relations between personality and coping, Edwards [24] found that one major pathway by which personality influences stress-outcome relations is through the different coping patterns adopted by individuals differing in personality. Coping also acts as a mediator between personality and health [25]. Direct measurement of coping behavior can, therefore, provide an alternative or complementary approach to use personality measures in explaining variation in health outcomes.

DeLongis and Holtzman [26] found that personality influenced coping and stress outcomes based on the situational context in which stress occurred. Although situational factors appear to explain the majority of variance in coping responses [27-29], personality plays an important role in almost every aspect of the stress and coping process, such as the likelihood of the occurrence of stressful events [30,31], appraisal of an event as stressful [32], using certain coping strategies [33,34], and the effectiveness or outcomes of these coping strategies [31,32]. Those high on Neuroticism cope poorly by choosing ineffective strategies that may intensify stressful situations whereas those high on Extraversion cope actively and are more likely to use various coping strategies effectively, including cognitive reframing and active problem solving [26]. However, there is limited research on the coping strategies of Type Bs since researchers often discount their ability to experience stress due to their easygoing and relax characteristics.

Coping and Disposition towards Gratitude

A theoretical rationale for the possible relation between dispositional gratitude and coping strategies is presented by Fredrickson [35], who suggests that since gratitude is a positive emotion, frequent experiences of gratitude would build enduring cognitive resources. She suggests that the broaden-and-build theory could offer a wider view on dispositional gratitude, and that through broaden-and-build processes grateful people could develop superior social and cognitive resources such as positive coping responses. According to Wood and colleagues [36], gratitude broadens thought action repertoires by causing one to habitually seek emotional and instrumental support, which leads to superior social and cognitive resources. These habitual thought action repertoires constitute grateful coping [16], which is an enduring positive affective state involving the predisposition to experience gratitude [37] along with a distinct pattern of coping strategies [38].

Grateful people can cope more effectively with everyday stress, show increased resilience despite trauma-induced stress, recover more quickly from illness, and enjoy more robust physical health [39-42].

Wood [36] Found positive correlations between gratitude and seeking both emotional and instrumental social support, positive reinterpretation and growth, active coping, and planning. While gratitude correlated negatively with behavioral disengagement, self-blame, substance use, and denial. Coping strategies appeared to mediate up to 51% of the relationship between gratitude and stress, and 11% of the relationship between gratitude and satisfaction with life. More specifically, grateful people were more likely to seek emotional and instrumental social support as a means of coping. They also generally used more positive coping strategies, broadly characterized by approaching the problems (using positive reinterpretation and growth, active coping, and planning) rather than avoiding the problems (behavioral disengagement, self-blame, substance use, and denial). Certain coping strategies are related to well-being and possessing adaptive coping strategies could explain the emotional benefits of having a grateful disposition [36]. Mofidi [43] found that trait gratitude was consistently related to each aspect of grateful coping in their research lending further evidence that these particular coping styles are reflective of a grateful outlook on life. Therefore, coping may partially explain why grateful people are less stressed

Personality and Disposition towards Gratitude

Although there is considerable research on gratitude and personality, the focus is more on gratitude as a trait rather than in correlation with a personality type. McCullough and colleagues [15] found that people who rated themselves as having a grateful disposition perceived themselves as having prosocial characteristics. Experimental research supports the prosocial nature of gratitude [44, 45]. “The prosocial nature of gratitude suggests the possibility that the grateful disposition is rooted in the basic traits that orient people toward sensitivity and concern for others [15].” Saucier and Goldberg [46] found that people who rated themselves (or other people) as particularly grateful also rated themselves (or other people) as higher in agreeableness (r = .31).

Individuals with a grateful disposition are thankful for the good things that occur in their lives and acknowledge others’ contributions. The grateful disposition also correlated with other Big Five factors, such as neuroticism (negatively), extraversion (positively), conscientiousness (positively), and openness (positively) [15]. However, despite these robust correlations, the Big Five only accounted for approximately 30% of the variance in the disposition towards gratitude, indicating that the grateful disposition cannot be reduced to a linear combination of the Big Five.

The association between gratitude and the seeking of emotional and instrumental social support is consistent with conceptions of gratitude as a socially oriented personality trait [36]. Neto [47] indicated that gratitude is a significant predictor of trait forgiveness i.e., it explained a significant amount of variance beyond the personality domains for overall tendency to forgive.

In their case study, Emmons and Stern [39] found that gratitude had one of the strongest links to mental health and satisfaction with life than any personality trait-more so than even optimism, hope, or compassion. Grateful people experience higher levels of positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, love, happiness, and optimism, and gratitude as a discipline protects us from the destructive impulses of envy, resentment, greed, and bitterness.

In summary, both situational factors and personality factors play a significant role in coping. Type A individuals or those having characteristics of Type A personality tend to report greater use of active coping, planning and suppression of other activities than Type Bs. However, more researches are needed on Type B people to elucidate the difference. Grateful disposition was linked with pro-social characteristics suggesting that it is rooted in the basic traits that orient people toward sensitivity and concern for others. It also correlates well with Big Five personality traits. It is strongly linked to mental health and satisfaction with life. Grateful people also experience higher levels of positive emotions. According to Fredrickson [35], frequent experiences of gratitude help build cognitive resources such as grateful coping, which is an enduring positive affective state involving the predisposition to experience gratitude along with a distinct pattern of coping strategies reiterating the idea that gratitude as a positive emotion can be quite useful in diversifying our coping strategies. It also has a positive influence on a person’s mental and physical health.

OBJECTIVES

In a sample of counsellors and psychologists, the current research aimed to study:

- whether Type-A personality differs from Type-B personality in their use of coping strategies

- the disposition of Type A/B people towards gratitude

- the relationship between gratitude and coping strategies (EF, PF, and combined) in the total sample

HYPOTHESES

H1: People with Type A and Type B personalities will differ significantly in the coping strategies used by them.

H2: People with Type A and Type B personalities will differ significantly in their disposition towards gratitude.

H3: People with Type A personality will be positively correlated with problem-focused coping strategies and negatively correlated with emotion-focused coping strategies.

H4: People with Type A personality will be negatively correlated with disposition towards gratitude.

H5: People with Type B personality will be positively correlated with emotion-focused coping strategies and negatively correlated with problem-focused coping strategies.

H6: People with Type B personality will be positively correlated with disposition towards gratitude.

H7: It is expected that there will be a positive correlation between disposition towards gratitude and coping.

H8: There will be a significant correlation between disposition towards gratitude and emotion-focused coping.

H9: There will be a significant correlation between disposition towards gratitude and problem-focused coping.

METHOD

Design: An ex-post facto exploratory research design was used to test the hypotheses.

Participants

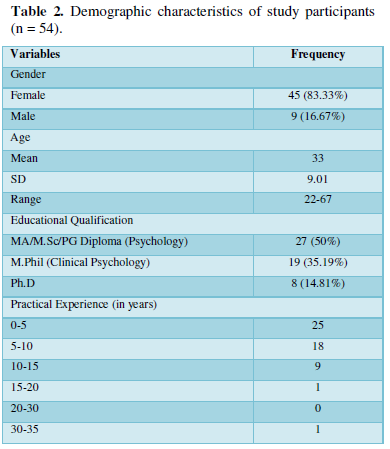

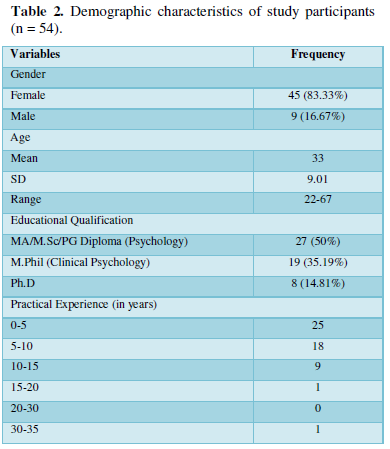

The ethical considerations were reviewed. Informed consent was sought from the participants before recruiting them for the study. Using purposive sampling technique, data was collected between September 2018 and November 2018. In all, 92 professionals (clinical psychologists and counsellors) volunteered to participate. There was missing data for 38 participants. The final sample constituted 54 professionals comprising clinical psychologists and counsellors. The participants’ mean age was 33 years with standard deviation of 9.01. Of the 54 respondents, 45 were female (83.33%). The practical experience of the professionals ranged from 2 years to 32 years.

Inclusion criteria

Individuals who met the following criteria were included in the study

- Clinical Psychologist and/or Counsellor (in any area of Psychology)

- A minimum 2 years of experience in the practical field

Measures

The Demographic Profile Sheet, the Gratitude Questionnaire [15], the Framingham Type A Scale [48] and the Ways of Coping Scale [49] were used.

Demographic Profile Sheet was created to gather participants’ socio-demographic information excluding name and contact information to provide assurance for response confidentiality.

Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) [15] was used to measure the disposition to experience gratitude by the participants in their daily life. This six-item self-report questionnaire is based on a 7-point Likert Scale (1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree). Two items are reverse-scored to inhibit response bias. The score on this scale ranges between 6 and 42 points. Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the six- item totals have ranged from .76 to .84. The GQ-6 has good internal reliability, with alphas between .82 and .87.

Framingham Type A Scale (FTAS) [48] was used to measure Type A Behavior Pattern, developed as part of the Framingham Heart Study. It comprises 10 items that evaluate specific Type A features related to competitive drive, sense of time urgency, and perceived job pressure. Scoring the Framingham Scale involves tabulating scores from weighted items to provide a cumulative Type A score. Individuals who score above the designated median are considered to be Type A and those scoring below the median are identified as Type B. The scores on this scale range from 5 to 40 points. Framingham Type A Scale was developed keeping both males and females in mind. Reliability coefficient of this test is .71 and .70 for men and women, respectively. The empirical and face validity of the test was reported to be high. Regarding convergent validity, Haynes [48] reported the following inter-scale correlation coefficients: (a) ambitiousness (.31), (b) emotional lability (.43), (c) tension (.42), (d) daily stress (.47) and (e) anger symptoms (.34).

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WOC) [49] was used to measure the coping processes used during stressful encounters. It is derived from the cognitive-phenomenological theory of stress and coping that is articulated in stress, appraisal and coping by Lazarus and Folkman [8]. It is a 66-item (50 rated items and 16 “fill in” items) self-report inventory with a 4-point Likert scale in which scores range from ‘1’ (Not Used), ‘2’ (Used Somewhat), ‘3’ (Used Quite a Bit) to ‘4’ (Used a Great Deal). Responses are scored into eight subscales which can also be classified in terms of their overall Problem focused or Emotion focused orientation. Higher scores indicate more frequent use.

The WOC contains the following eight empirically derived subscales.

- Confrontative Coping: Describes aggressive efforts to alter the situation and suggests some degree of hostility and risk taking.

- Distancing: Describes cognitive efforts to detach one self and to minimize the significance of the situation.

- Self-control: Describes efforts to regulate one’s feelings and actions.

- Seeking social support: Describes efforts to seek informational, tangible and emotional support.

- Accepting responsibility: Acknowledges one’s own role in the problems with a concomitant theme of trying to put things right.

- Escape-avoidance: Describes wishful thinking and behavioral efforts to escape or avoid the problems. Items on this scale contrast with those on the Distancing scale, which suggest detachment.

- Planful problem solving: Describes deliberate problem focused efforts to alter the situation coupled with an analytic approach in solving the problem.

- Positive reappraisal: Describes efforts to create positive meaning by focusing on personal growth. It also has religious dimensions.

Respondents are asked to direct their ratings of real-life stresses experienced during the past 7 days. Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities, for the 8 subscales, ranged from 0.56 to 0.85. Inter-scale correlations ranged from -0.04 to +0.39. The questionnaire also exhibits adequate face validity and construct validity.

Procedure

A web-survey, including the aforementioned measures, was set up and run on a secure web server (Google Forms) for data collection. To collect a sample of willing participants, a message containing a brief study description, inclusion criteria, and a request to participate was circulated among psychologists and counsellors across India through social networking sites and applications. The E-mail Ids received from the willing professionals were then sent an official email describing the study and inclusion criteria along with the prepared survey link. Regardless of the recruitment method, all participants completed the study strictly through a mail questionnaire. Data was collected between 1st September and 3rd November 2018. Thereafter, the link was made inaccessible. Scoring was computerized.

Data Analyses

Excel, SPSS version 23 [50] and Vassarstats [51] were used for data analysis. The compiled data was on an ordinal scale; therefore, Spearman’s correlation was used to measure the relationship between the two ordinal variables that are related, but not linearly. t test was conducted to measure differences between people with Type A and Type B personality within the scales.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In a sample of counsellors and psychologists, the current research studied whether Type-A personality differed from Type-B personality in their use of coping strategies, the disposition of Type A/B people towards gratitude, and the relationship between gratitude and coping strategies. Table 2 presents the sample’s demographic distribution.

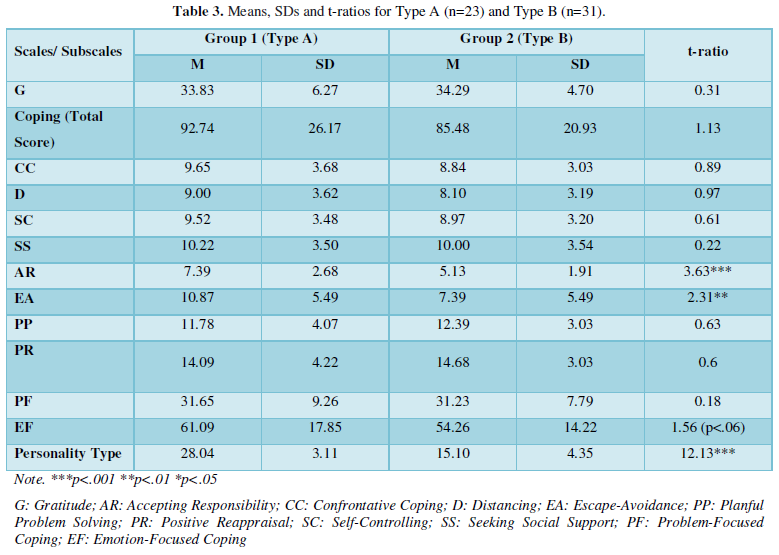

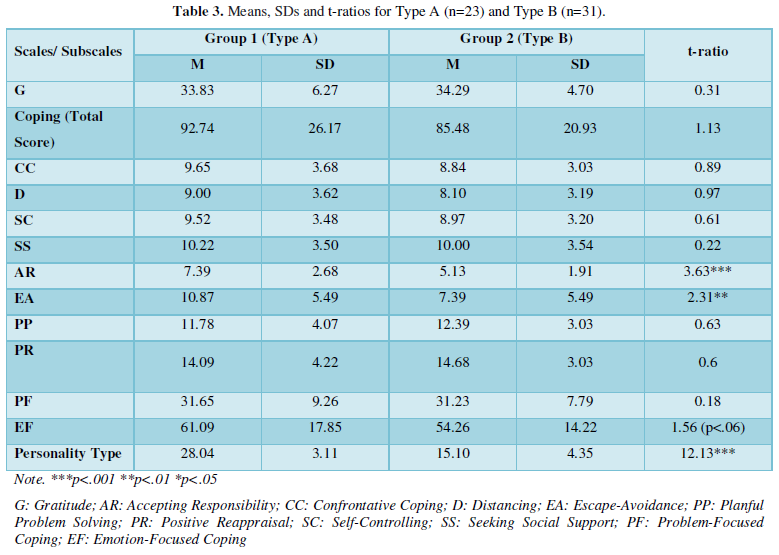

The t test revealed a statistically significant difference between Type A and Type B groups (Hypothesis 1) on a) the coping strategy of accepting responsibility (AR) (t = 3.63, df = 52, p<.001), b) the coping strategy of escape-avoidance (EA) (t = 2.31, df = 52, p<.01), and c) emotion-focused coping strategies (t = 1.56, df = 52, p<.06) with Type A individuals having higher means than Type B (Table 3). These findings are supported by Carver et al. [18] and Latack [21], who found that Type A individuals reported greater use of active coping, planning, and suppression of other activities than Type Bs. Although, there is a dearth of studies in this regard with psychologists and counsellors as sample, understanding these results considering the studies done on lay population or the lack of studies on Type B personalities can be misleading and may reveal half-truths. Considering how well-equipped and unique this sample is, the lack of statistically significant difference between Type A and Type B personalities should not be surprising. Psychologists and counsellors have clinical training in using a wide range of coping strategies. It is, therefore, quite possible that over time, clinical training combined with practical experience with varying client and personal situations, they have moved beyond their personality characteristics and engage in whatever strategy suits them best in that situation. In this study, positive reappraisal and planful problem-solving coping strategies were used more on an average by both Type A and Type B groups as well as the overall sample. In a study by Prochaska [52], psychotherapists reported using helping relationships significantly and more frequently than the laypersons. This difference was attributed to the interpersonal emphasis of the profession and stronger social support network for psychotherapists. Predictably, psychotherapists would be expected to find interpersonal coping processes both satisfying and efficacious, whether it is for themselves or their patients [53].

No significant difference (Table 3) was found between Type A and Type B personalities in their disposition towards gratitude (G), thereby rejecting hypothesis 2. Maximum participants (96.29%) in the present study scored high on dispositional gratitude irrespective of their personality type. It suggests that the clinical training and practical experiences may have helped develop or enhance their disposition towards gratitude over time that may not be associated with their personality type. The literature on gratitude and personality focuses more on gratitude as a trait than in correlation with a personality type. Therefore, this finding partly supports the results of Emmons and Stern (2013) that gratitude has one of the strongest links to mental health and satisfaction with life than any personality trait. There is also an association between gratitude and the seeking of emotional and instrumental social support [36].

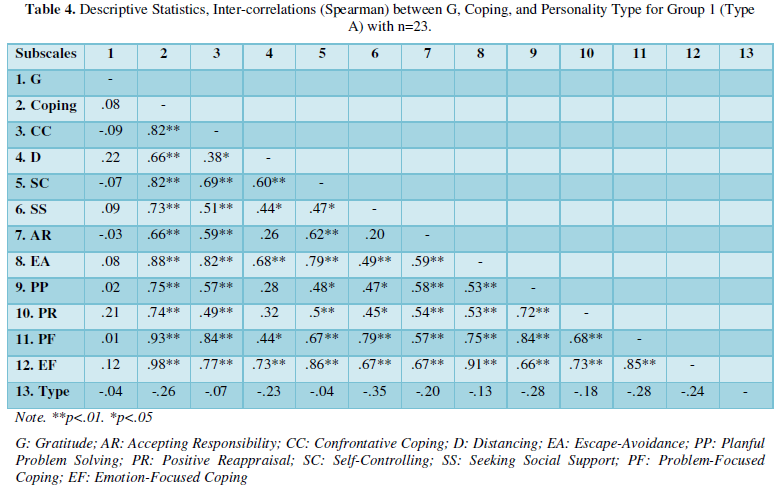

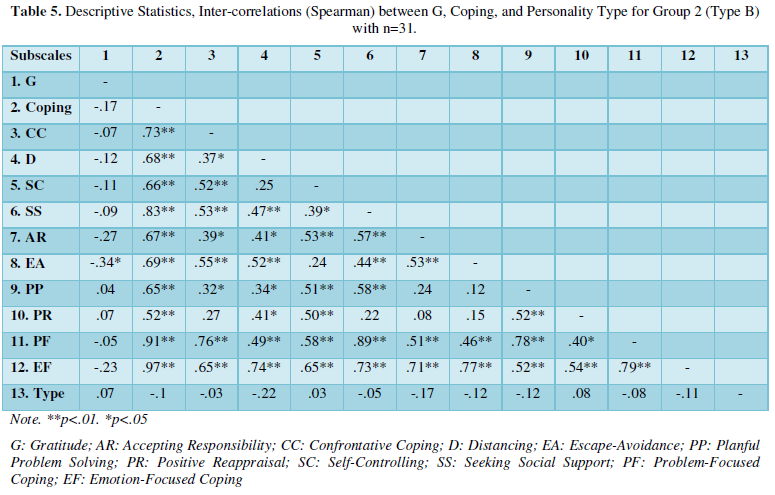

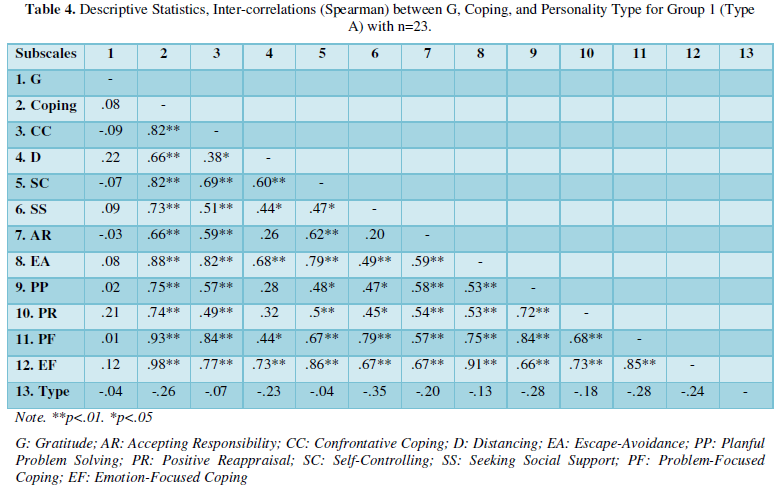

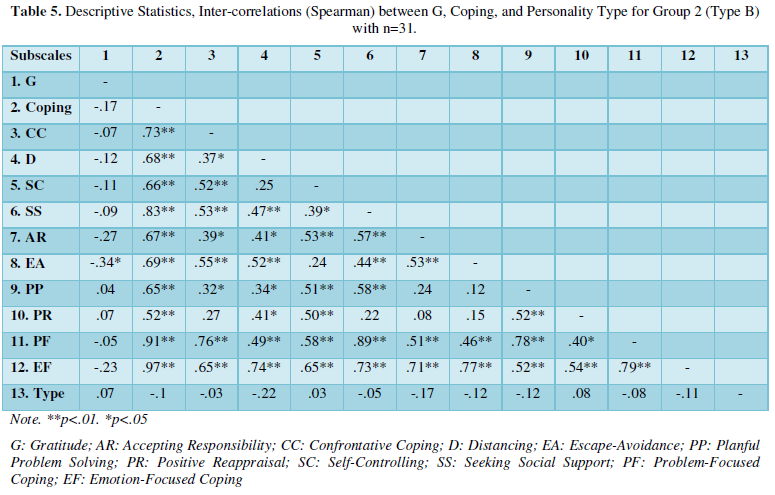

No significant correlations were found between Type A personality and problem-focused coping strategies, and Type A personality and emotion-focused coping strategies (Hypothesis 3; Table 4). No significant correlations were found between Type B personality and emotion-focused coping strategies, and Type B personality and problem-focused coping strategies (Hypothesis 5; Table 5). These hypotheses were not based on an earlier study or a pre-existing hypothesis but on the basis of the characteristics of the personality Types A and B. None of these hypotheses are found to hold their ground. Neither did we find any support for these predicted correlations.

No significant correlations were found between Type A personality and disposition towards gratitude (Hypothesis 4; Table 4), and between Type B personality and disposition towards gratitude (Hypothesis 6; Table 5). Despite the fact that 96.29% of the sample scored high on gratitude, there was no significant correlation found between Type A or Type B personality and disposition towards gratitude. It can be inferred that, in such a sample, personality type does not have an association with gratitude as much as a personality trait does (Emmons and Stern, 2013; McCullough et al., 2002). Despite robust correlations with the Big Five, the Big Five only accounted for approximately 30% of the variance in the disposition towards gratitude, indicating that the grateful disposition cannot be reduced to a linear combination of the Big Five. Additionally, the high scores on gratitude, as speculated earlier, maybe attributed to the clinical training and practical experiences which may have led them to develop or enhance their disposition towards gratitude over time that may not be associated with their personality type.

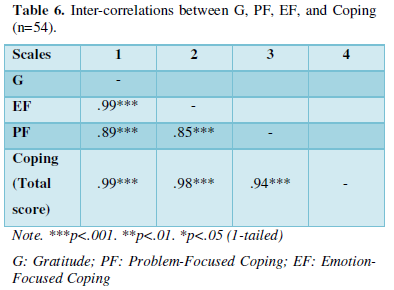

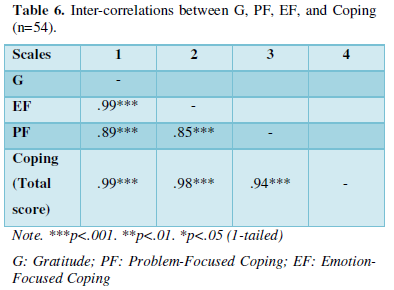

A significantly high positive correlation was found between G (disposition towards gratitude) and Coping (r = .99, p< .001; Table 6) in the total sample, substantiating Hypothesis 7.

As shown in Table 6, a significantly high positive correlation was found between G and EF strategies (r = .99, p< .001), substantiating Hypothesis 8.

A highly significant positive correlation was also found between G and PF strategies (r =.89, p< .001; Table 6), substantiating Hypothesis 9.

The relationship found between disposition towards gratitude and coping (hypotheses 7, 8, & 9) is consistent with the previous research. Theoretically, gratitude is a positive emotion and frequent experiences of gratitude builds enduring cognitive resources [35]. According to the broaden-and-build theory, gratitude broadens thought-action repertoires by causing one to habitually seek emotional and instrumental support, which leads to superior social and cognitive resources [28]. Psychotherapists have been found to engage more in seeking helping relationships than laypersons [52,53] and also have strong social support networks. Researchers have also found that people who experience gratitude can cope more effectively with everyday stress, show increased resilience against trauma-induced stress, recover more quickly from illness, and enjoy more robust physical health [39-42].

CONCLUSION

In summary, unsurprisingly no significant difference was found between Type A and Type B psychologists and counsellors concerning coping strategies, indicating that personality type may not influence their use of coping strategies in this unique sample. Personality type, however, may influence more frequent use of a particular type of coping strategy. For example, Type A individuals were found to use AR, EA, and EF coping strategies more than Type B individuals. This lack of difference can be linked with the positive effect of participants’ clinical training and practical experience. Positive reappraisal and planful problem-solving were also used more on an average by both Type A and Type B individuals. Maximum participants (96.29%) were high on gratitude irrespective of their personality type. Despite this, no significant association was found between type A and gratitude, and type B and gratitude. This suggests that personality type may not be associated with gratitude among psychotherapists. Also, a strong correlation was found between gratitude and coping in this sample.

Psychologists and counsellors are fully equipped with using positive reinterpretations, have a wide array of coping strategies at their disposal, do not stick to one particular kind of coping and can enhance or develop qualities that can benefit their mental and physical health. Therefore, it can be inferred that clinical psychologists/counsellors may avoid many pitfalls and successfully cultivate sustainable well-being through understanding and putting into practice a broad-based and increasingly evidence-based framework to living a grateful and healthy life.

Strengths and Limitations

This research addresses a gap in literature that has been largely untouched in India. It includes a sample of clinical psychologists and counsellors, which can provide us insight into how training, practice, and experience can render certain aspects of our personality ineffective, and help us develop and enhance our overall wellbeing. The method of data collection was strictly mail questionnaire. High levels of confidentiality and anonymity were maintained. There was no incentive for participation. Slow response or no response using mail questionnaire was a limitation. The sample was not randomly selected. Therefore, it is not representative of the entire population.

Future Recommendations

Future researches can study the traits of Type A/B personalities that are linked with a grateful disposition in such a sample. Research on how cultivating the qualities of a psychotherapist such as positive reinterpretation, optimism, introspection, etc., can benefit students can also help establish psychology as a subject in schools not only for senior secondary but also for primary and secondary classes. A longitudinal study can also be done to trace and study the development or enhancement of skills of psychologists and counsellors and how their personalities change over time with their increasing clinical experience.

- Kahn BK, Hansen ND (1998) Rafting the rapids: Occupational hazards, rewards, and coping strategies of psychotherapists. Prof Psychol Res Pract 29: 130-134.

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/personality/

- Carducci BJ (2009) The Psychology of Personality, Second edition. UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Rees WL (1990) Etiological factors in Asthma. Psychiatr J Univ Ott 5: 250-254.

- Cooper CL, Kirkcaldy BD, Brown J (1994) A model of job stress and physical health: The role of individual differences. Pers Individ Differ 16: 653-655.

- Dembroski TM, Dougall JM, Shields JL, Pettito J, Lushene R (1978) Components of the Type A Coronary-prone behavior pattern and cardiovascular response to psychomotor performance challenge. J Behav Med 1: 159-176.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS (1988) The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med 26: 309-317.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS (1985) If it changes it must be a process. J Pers Soc Psychol 48: 150-170.

- Darshani RKND (2014) A Review of personality types and locus of control as moderators of stress and conflict management. Int J Sci Res 4.

- Baqutayan SMS (2015) Stress and Coping Mechanisms: A Historical Overview. Mediterr J Soc Sci 6: 479.

- Goodenough U (1998) The sacred depths of nature. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Emmons RA, Cullough MEM (2003) Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol 84: 377-389

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Maltby J (2008) Gratitude uniquely predicts satisfaction with life: Incremental validity above the domains and facets of the five-factor model. Pers Individ Differ 45: 49-54.

- Cullough MEM, Emmons RA, Tsang J (2002) The Grateful Disposition: A conceptual and Empirical Topography. J Pers Soc Psychol 82: 112-127.

- Watkins PC, Gelder MV, Frias A (2009) Furthering the science of gratitude. In S. Lopez & R. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed). NY: Oxford University Press.

- Amirkhan JH (1990) A factor analytically derived measure of coping: the coping strategy indicator. J Pers Soc Psychol 59: 1066-1074.

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 56: 267-383.

- Parkes KR (1984) Locus of control, cognitive appraisal and coping in stressful episodes. J Pers Soc Psychol 46: 655-668.

- McCrae RR, Costa PT (1986) Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. J Pers Soc Psychol 54: 385-405.

- Latack JC (1986) Coping with job stress. J Appl Psychol 71: 377-385.

- Bolger N (1990) Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol 59: 525-37.

- Contrada R, Czarnecki E, Pan R (1997) Health-damaging personality traits and verbal-autonomic dissociation: The role of self-control and environmental control. Health Psychol 16: 451-457.

- Edwards JR, Baglioni AJ, Cooper CL (1990a) Stress, Type-A. Coping, and psychological and physical symptoms: a multi-sample test of alternative models. Human Relations 43: 919-956.

- Williams PG, Wiebe DJ, Smith TW (1992) Coping processes as mediators of the relationship between hardiness and health. J Behav Med15: 237-255.

- DeLongis A, Holtzman S (2005) Coping in Context: The role of Stress, Social Support and Personality in Coping. J Pers 73(6): 1633-1656.

- O’Brien TB, DeLongis A (1997) Coping with chronic stress: An interpersonal perspective. In B. H. Gottlieb (Ed.), Coping with chronic stress. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation.

- Parkes KR (1986) Coping in stressful episodes: The role of individual differences, environmental factors, and situational characteristics. J Pers Soc Psychol 51: 1277-1292.

- Terry DJ (1994) Determinants of coping: The role of stable and situational factors. J Pers Soc Psychol 66: 895-910.

- Bolger N, Schilling EA (1991) Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. J Pers 59: 355-396.

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A (1995) A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol 69: 890-902.

- Gunthert KC, Cohen LH, Armeli S (1999) The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. J Pers Soc Psychol 77: 1087-1100.

- David JP, Suls J (1999) Coping efforts in daily life: Role of big five traits and problem appraisals. J Pers 67: 265-294.

- Costa PT, Crae RRM (1985) The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Fredrickson BL (2004) Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In RA Emmons & ME McCullough (Eds.), the Psychology of Gratitude (145-166). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Linley PA (2007) Coping Style as a Psychological Resource of Grateful People. J Soc Clin Psychol 26: 1076-1093.

- Watkins PC, Woodward K, Stone T, Kolts RL (2003) Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Soc Behav Pers 31: 431-452.

- Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 56: 218-226.

- Emmons RA, Stern R (2013) Gratitude as a Psychotherapeutic Intervention. J Clin Psychol 69: 846-55.

- Barusch AS (1997) Self-concepts of low-income older women: Not old or poor, but fortunate and blessed. Int J Aging Hum Dev 44: 269-282.

- Coffman S (1996) Parents’ struggles to rebuild family life after Hurricane Andrew. Iss Ment Health Nurs 17: 353-367.

- Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D (2005) Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Rev Gen Psychol 9: 111-131.

- Mofidi T, Alayli AE, Brown AA (2014) Trait Gratitude and Grateful Coping as they relate to college student persistence, success and integration in school. J Coll Stud Ret16: 325-49.

- Tsang J (2006) Gratitude and prosocial behaviour: An experimental test of gratitude. Cogn Emot 20: 138-148.

- Bartlett MY, DeSteno D (2006) Gratitude and Prosocial Behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci 17: 319-325.

- Saucier G, Goldberg LR (1998) What is beyond the big five? J Pers 66: 495-524.

- Neto F (2007) Forgiveness, Personality and Gratitude. Pers Individ Differ 43: 2313-2323.

- Haynes SG, Feinleib M, Levine S, Scotch N, Kannel WB (1978) The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham Study II: Prevalence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 107: 384-402.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS (1988b) Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

- IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Lowry, R. (1998). VassarStats: Website for Statistical Computation. U.S.

- Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, Diclemente CC (1986) Psychotherapists' self-change vs. laypersons' self-change: A comparative analysis of treatment strategies. J Clin Psychol 42(5): 834-840.

- Norcross JC, Prochaska JO (1986) Psychotherapist heal thyself-I. The psychological distress and self-change of psychologists, counsellors and laypersons. Psychother 23: 102-114.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Allergy Research (ISSN:2642-326X)

- Journal of Nursing and Occupational Health (ISSN: 2640-0845)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- Journal of Pathology and Toxicology Research

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- Journal of Cancer Science and Treatment (ISSN:2641-7472)