Research Article

Reproductive Health, Poverty and Social Inclusion of Combatants’ Daughters in Higher Education: A Proposal to Rovuma University in Mozambique

742

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Introduction: This article is a proposal on how the Rovuma University (UniRovuma) can be an instrument for the social integration of marginalized groups in Mozambique, in this case, the daughters of former freedom fighters. It started from the observation that it is possible to have a scholarship for a specific group after the University has decided to enroll (without entrance exams) about 111 students from military conflict areas in Cabo Delgado, in April 2021. The fact is that in addition to the armed conflict victims, there are other anonymous victims such as the former combatants’ daughters who suffer a double stigmatization of society; first because of being the ex-combatants’ daughters and, second, because they are women. As a general rule, Mozambican society does not respect former freedom fighters, which affects their descendants, especially females. When there is an opportunity for study or employment, boys are who benefit from them. If a man shows up promising them marriage, they are forced to drop out of school by their elders and, as housewives, they have to stay at home to take care of it and their parents. Because they get married early, they tend to have many children, which hinders their economic and reproductive life. Our proposal is that, if they have the opportunity to study in higher education, as happened with military conflict victims, they will not only be able to improve their reproductive life, but also cut the cycle of poverty that characterizes them. But that means offering them an incentive, one of which is a scholarship that we propose.

Objective: to contribute to the design of techniques and mechanisms for the inclusion and retention of girls in Mozambican higher education in order to reduce social inequalities based on gender.

Methods: This study is the result of field research carried out in two moments and with two distinct groups, one of which served as an experiment on the possibility of implementing a gender inclusion policy that can be genuinely designed to contribute in fact. The first study was conducted from September to November 2020 in Murrupula district (about 70 km from Nampula) and involved around 800 former freedom fighters and their families. The existence of the coronavirus pandemic greatly interfered on data collection so the first phase’s period was very long. First, our focus was on girls who have not yet had the opportunity to enter university and then we worked with those who are already at the Rovuma University, believing that the difficulties of those girls who have already advanced in their studies can serve as examples to others who wish to also move forward. The second phase of the study took place from January to April 2021 in the Mozambican provinces of Nampula, Niassa and Cabo Delgado, where UniRovuma is present with the participation of the female academic community from the aforementioned university. Interviews, questionnaires and observation were used as research instruments for data collection. In addition, the normative documents from both the former combatants and the UniRovuma were consulted and the students’ statistical data, teachers and administrative staff number, in their representation by gender, were analyzed. The students’ lists enrolled in the first year were analyzed, following their evolution until the following years. The special focus in the female academic community was directed to girls who appeared to have low academic performance, where we sought to know the conditions, they were in when they took the exam or test. Outside the University, ex-combatants were asked about their expectations and those of their descendants, as well as how they see the higher education role and the results of the armed struggle in which they participated.

Results: This is a new and unprecedented work both in the country and at Rovuma University, since there are not many studies focused on microsociology and mainly on specific groups such as the freedom fighters’ descendants. If freedom fighters are more studied in Mozambique, their descendants do not deserve the same special attention from researchers. In the microsociology specialization area, the theme is important because it brings light to rethink approaches that lead to lasting solutions for concrete problems in Murrupula. Recently, Rovuma University admitted, without passing the entrance exam, more than a hundred children whose parents were victims of the armed conflict that is taking place in Cabo Delgado province, where terrorist groups have been in military confrontation with the Mozambique Defense Armed Forces. On the basis of this, we believe that it is possible to replicate the same model to other marginalized groups. In fact, two immediate results may emerge from this study, in the medium term. The three provinces where UniRovuma is present have 56 districts. If Rovuma University manages to recruit 56 girls a year - the equivalent of one girl per district - by placing them in the technical areas, it will have trained 280 girls in each cycle of five years. Likewise, if Rovuma University awards five scholarships per district each year, at the end of the five-year cycle it will have train 1,400 women in higher education, which will represent a revolution in a country where women remain marginalized.

Conclusion and recommendation: Just as it were sensitive to the case of victims of the armed conflict in Cabo Delgado, the Rovuma University Rectory must have the same sensitivity towards other marginalized groups, creating a grant specifically aimed at women from the most disadvantaged social classes. But this sensitivity must also take into account the creation of internal conditions within the university to continue removing the obstacles that push girls who are already studying to drop out. It is true that university education is offered on an equal footing between boys and girls. However, as this study will reveal, there are particular characteristics of women that interfere in their learning process and that should deserve the attention from managers of the educational process. In other words, studies must be carried out to ensure that women are not victims of their biological condition as a woman.

Keywords: Murrupula, Gender, Rovuma University (UniRovuma), Sexism, Former freedom fighters’ daughters

INTRODUCTION

This article is part of a specific case study at Rovuma University in Mozambique, where a gender policy is designed not only to increase the number of girls at the University but also to include them in technical knowledge areas. In fact, the Rovuma University’s Rectorate launched a project to realize the women empowering idea in the northern part of Mozambique. The idea is based on the assumption that women’s empowerment is a way of reducing family poverty and women’s dependence on men. Therefore, this article does not only examine the social factors of women’s exclusion from higher education. It initiates some rifle.

THE PROBLEMATIZATION

In March 2020, the Rectorate of Rovuma University (Uni Rovuma) gave us a task to investigate two issues related to women. The first one was about the participation of Macua women (the majority ethnicity living in northern Mozambique) in the armed struggle for national liberation. The second task focused on the main concerns of girls attending this university, which was created in 2019 following the breakup of the Pedagogical University, from which were five other universities emerged. The first mission not only revealed us the miserable lives of former freedom fighters, but also showed that their daughters never had the opportunity to receive the highest level of education. Although former freedom fighters send their daughters’ lists to enter university every year according to the agreements signed for this purpose in the past, these daughters are never accepted. When we tried to find out why the children of combatants did not study at the highest levels, the answer we were given was that, in the first place, as primary education is free, the parents’ poverty does not interfere with their children’s lack of education. Unlike primary education, admission to tertiary education is paid. As parents do not have the money to enroll their daughters in the entrance exam, it is impossible to make this dream come true, although there is never a lack of desire. Back at Rovuma University, we raised this concern with some individuals. Our conversation served as a probe to see if it would be possible to create a loophole in which the former freedom fighters’ daughters could enter university without the entrance exam, due the lack of money. The unanimous response was that this would not be possible because it would violate the regulation that requires all students at the Rovuma University to apply for the entrance exam. Meanwhile, the military conflict in Cabo Delgado intensified. The Rectory thought it was good for the university to receive the children of parents who were victims of that conflict because, as was justified, their parents had lost everything. This suggestion was accepted and praised. From this episode on, our understanding of the possibility or not of placing students without the entrance exam changed. We were now increasingly convinced that it is possible to offer scholarships for specific groups. And freedom fighters are not just a specific group; they preserve the symbolism that Mozambicanity keeps in the annals of its history. As the former freedom fighters themselves claim, their place is occupied by the daughters and sons of the chiefs living in the provincial capital. The common ignorance among the descendants of former freedom fighters is reproducing not only poverty in Murrupula, but also cyclical violence in a vicious circle. Several times the government has promised them a peace fund [1] but its fate is also unknown. Former combatants who feel cheated tend to be easy prisoners for any armed group that wants to recruit men, as seen in the armed disturbances that since 2012 have found fertile ground in Murrupula. In terms of reproductive health, the former freedom fighters’ daughters, because they are poor, they see the number of their children as a support and a blessing to assist them in various domestic activities, as their parents believed in the past. Women’s health has been affected by many factors, such as psychosocial factors resulting from a woman’s family environment, society, work and personal characteristics, including her fertility status. If, worldwide, women’s life expectancy is higher when compared to men, in almost all societies women suffer more illness and stress than men [2]. The purpose of the second task was to create the basic conditions for the formulation of an institutional gender representation policy at UniRovuma. In the first case, if the exclusion of the former freedom fighters’ daughters in education was notorious, in the second case, it was clear that women as all were underrepresented both in the University and in the so-called exact or technical sciences. Women often experience dramatic moments in the classroom, at work or on a walk when their condition as a woman is not always taken into account by prevailing sexism. No one denies that great strides have been made in ensuring women’s rights and countries and institutions have sought to design and implement gender equality policies in different ways. The establishment of international mechanisms to ensure gender equality resulted from an understanding that equality transcends national borders and is an indication of the existence of a problem of socially and politically accepted inequality between men and women. Creating mechanisms for women’s advancement and social inclusion means accepting that the inequality of which they are victims can be transformed into equality through these mechanisms [3]. In the first case, we look at students from Rovuma University. In addition to them, this article analyzed the academic situation of former freedom fighters’ daughters from their parents’ educational background. It was assumed that studies carried out by parents are a model for their children to study as well. However, as many ex-combatants did not study because at school age they were fighting for the country’s freedom, later on, their children also did not study due to the lack of models, causing a vicious cycle of both illiteracy and poverty from which entire families cannot escape. Although the national armed struggle for the liberation was worthwhile for the majority of the people, for the combatants themselves it was not worth it, unless efforts were made to include them in the benefits of independence. One of the benefits of independence is, without a doubt, study. The ex-combatants are old and they recognize that. As a reward, they insistently ask government that their children and grandchildren study to care for their old age with a dignity that the government has failed to give them. In Murrupula, where there is a matrilineal kinship system, the ones who take care of the elders are usually the daughters, so our choice for this social group. In addition to biological factors, the health status of many women around the world deteriorates for socioeconomic reasons and the risk of contracting diseases is greater in women with inadequate economic conditions. Women with economic and, consequently, health problems will also not be able to contribute to both the domestic and national economy [2]. Therefore, it is necessary to break the cycle caused by this indirect relationship between economic status and women’s health. One of the best ways is to strengthen mechanisms for the social advancement of women, including quality education. There are many taboos surrounding women’s rights to education. Society resists sending their daughters to school for fear that their parents will not have the necessary support, as girls who study tend not to return to the village. Rovuma University can play an important role in the process of transforming minds, as the lack of opportunities for access to higher education can lead to failure and dropout. As seen, children from poor and uneducated families generally fail high school and college entrance exams. The fact that the children from a poor family are also poor and cannot escape this spiral of poverty reveals the importance of the correlation of forces between poverty and lack of education. In addition, parents’ academic qualifications say a lot for their children’s future. The link between the qualifications of parents and children is expressed by the social mobility concept. Indeed, children from families with educational levels above a certain threshold can achieve a high level of education and quality of life.

THE ROVUMA UNIVERSITY AND ITS WEAKNESSES

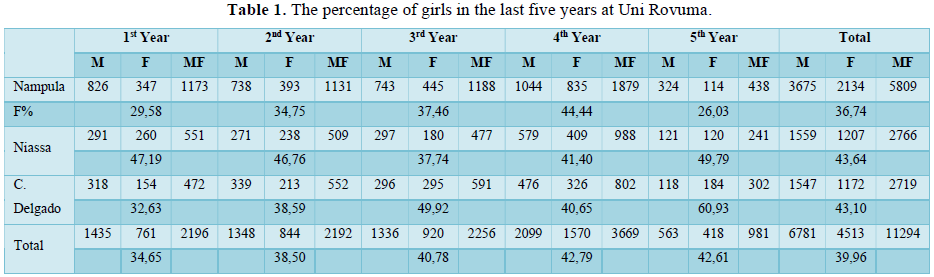

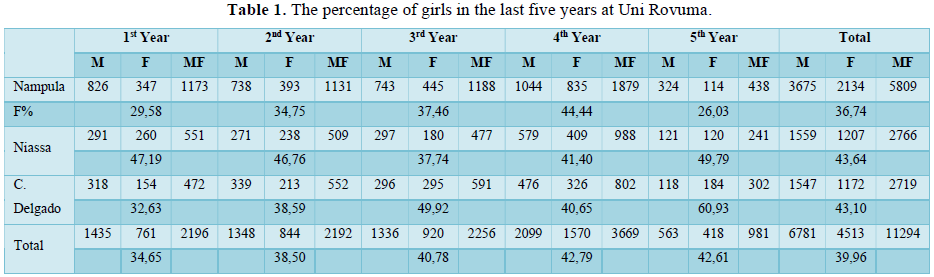

Anyone who deals with the study of the struggle’s women have been waging around the world [4] knows that, although the last years of the 20th century have shown great advances in gender relations, studies at the micro level highlight that discrimination and social exclusion based on gender still has profound implications for women’s participation in the labor market, in education and in society as a whole [5]. Worldwide, several studies have been and are being published on gender discrepancies, covering from the broadest topics, such as sexuality, employment, to the reproduction and sexual freedom issues. The same is true for scientific production, where women’s articles are cited less than men [6]. Of course, since the resumption of feminism in the late 1960s, scientific work and technological development have been under the constant gaze of the feminist gaze. And it was through this view that it became evident that the different disciplines were constituted from the exclusion (or distorted representation) of women’s lives and experiences, based on discriminatory practices that gave rise to male predominance among scientists, especially in the natural sciences field. As a result, in this, as in other fields of knowledge, an androcentric bias also prevailed in the choice and definition of the problems addressed, as well as in the design of projects and interpretation of the results obtained, which also had consequences for technological developments [5]. Several countries have included the debate on the women emancipation in their teaching programs, but such programs are designed by men who, as expected, conceive them according to their preferences. In Mozambique, gender studies are also carried out [7] and their contents are included in the first level of the national education system. İn higher education, content about women’s rights and their struggles and achievements are scarce. The debates’ paucity on gender and related rights in higher education means that women’s reproductive health issues and debates in this regard are ignored, remaining taboo among students. When we talk about reproductive and sexual health, the basic elements of the concept are related to the normal functioning of the female reproductive organs; In addition to a healthy and happy sex life, it is the ability to live sexuality and fertility without coercion, to decide whether to have children or when and how many children to have. But it also means having healthy children as a result of planned pregnancies. Reproductive health, reproductive system, functions and related processes are not only the absence of diseases and disabilities, but also the complete physical, mental and social well-being of all of them. Reproductive health also means that people have a satisfactory and safe sex life, the ability to reproduce and the freedom to decide to use their reproductive skills [8]. Now, if women live in extreme poverty and ignorance, it is impossible to experience all this. Although the women’s participation in higher education has increased across the country, and in particular at Rovuma University, they are still underrepresented both by their region of origin and by social characteristics, which means that so-called women from disadvantaged families continue to face all difficulties in accessing higher education. If general education is apparently free, the same cannot be said for public higher education in Mozambique. There are two obstacles in the way, all related to poverty. The first obstacle is the entrance exam, which is performed centrally. As former combatants are unable to buy books and other modern means of disseminating knowledge to offer their daughters, those do not pass the entrance exam and end up failing. The parents’ lack of money means that their daughters do not have the money to go to university. In other words, the entrance exam and the dependence of daughters on poor parents prevent them from entering higher education. This is where the central problem lies. Evil and weakness are identified. As we can see, there is a vicious cycle here. Combatants cannot send their daughters to university because they are poor as a result of which they are poor because they could not study while fighting to free the country from the colonial yoke. Therefore, it is necessary to alleviate one end of the problem to break the vicious cycle as a whole. What to do to get around this. The wealthy families avoid the embarrassment that the entrance exam brings to their daughters, sending them to private universities, which the ex-combatants cannot dream because of the petty pension they receive. The socially unprotected strata women’s exclusion from higher education means that their potential is not being used for the country’s development. Women, excluded from productive work, are anchored in craft work, basic needs and social welfare, linked to reproduction, that is, “the work performed by women ends up assigning them the place of users rather than producers of technology” [5]. However, a society in which women have a complete and accredited education in all areas of specialization can easily face a number of challenges, ranging from development issues, maternal and child health to home economics issues. If, on the one hand, the importance of female participation in higher education is increasingly recognized, on the other, the academic community seems to lack strategies to better understand the mechanisms that can stimulate the recruitment of disadvantaged women both for education and for the work. Rovuma University, which, although only existing for three years, has a history dating years ago when it was the pedagogical University that had poles across the country. From the Pedagogical University restructuring, five universities emerged, namely the Save University, the Licungo University, the Pungue University, the Rovuma University and a small part that remained the Pedagogical University. Of these five universities, Rovuma University is the largest in terms of both the number of students and the area in which it is located. However, in terms of qualified teachers and gender representation, Rovuma University is not the best. From the first to the fifth year, the number of students remained stable, but below 50%. It should be noted that the trend has decreased, being 34.65% in the first year and 39.96% in the fifth year. Considering that of the total of girls who enroll in the first year, 9,6% drop out during the course for different reasons, it can be concluded that these data are not encouraging. This reveals a relaxation in the policy of gender participation in education, so there is a need to work towards reversing the scenario. Analysis of the university’s statistical data reveals that in the three provinces under the jurisdiction of Rovuma University there are districts that are underrepresented or not represented by any students.

See the Table 1 below:

When the University was founded by the government as a public institution, it had in its statutes the mandate to transform itself into a classical University, in the sense of all courses in all areas of scientific knowledge. And gradually the University is taking part in these courses. From the very beginning, the direction of the new University had to map the region it was inserted into to learn about the deep needs in terms of scientific knowledge, and it was clear that engineering is the most sought-after course. This was because in the past and recent history of higher education in Northern Mozambique, the focus and investment has been more on the social, human and educational sciences. What remains to be done is the more practical and technical area. Because of this lack, the University has difficulty to create and manage courses in both practical and technical areas as it has very little experience. However, there are some courses that have recently been introduced such as: Civil engineering, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, electronics, geology and the computer course, which are more practical and recently introduced. However, these courses are not very strong and do not have enough stability as the teaching staff is very young and inexperienced. Rovuma University is in a good area with fertile land and plenty of water, the sea with beautiful beaches, but it is a poor region for beef production. She has to take the veterinary course as one of the bets and an agronomy course which is a weakness. Gas and oil, recently discovered in the same region where the University is located, are calling multinational corporations to the place where they set up platforms to extract these resources. Although the region has great potential for mineral resources such as rubies, gold, heavy sand, precious and semi-precious stones, the level of human development is low, economic development is low, and socio-economic conditions are very low. With multinational companies settling in this region, Mozambicans from this region who do not have a father and have never had the opportunity to get a scholarship to go abroad to study do not have access to the labor market. Therefore, they are automatically excluded from the labor market because they do not have the required qualifications. The multinationals want people to be trained in these areas of engineering and the most technical areas, and they want the region to offer beef because they need the meals and for all other aspects. However, Rovuma University is unable to offer anything despite all the conditions.

IMPACT OF THIS STUDY OVER THE NEXT FIVE YEARS

One of the questions may be how this scientific study is likely to bring about changes in the next 5 years. It is April 2021 and at this moment Rovuma University has just taken its entrance exam. In this exam, the number of girls who applied for the vacancies advertised was below 40%. Several factors may have contributed to the girls’ lack of interest in applying for the vacancies advertised, including the reduced number of vacancies proposed. In its editing, the university proposed the creation of small classes with between 20 and 30 students justified by the state of public clamor that the world goes through due to COVID-19. This study contributes for the number of girls at Rovuma University to grow more and more not only in general, but also in the exact sciences. In addition, we said elsewhere that Rovuma University was created to respond to the needs of higher education in northern Mozambique. As such, it does not make sense for districts to be underrepresented in terms of female students. Our proposal is that ‘in the future, Rovuma University can contact the district directorates where there are secondary schools that offer the average level of schooling. When contacting the boards of these schools, it is possible to identify 5 students per district to be sent to the university to fill the vacancy of the scholarship to be proposed. We have to cut the cycle of women’s exclusion from the educational system with determined proposals. The exclusion of women from scientific and technological activities was based on scientific discourses, which postulated, based on biological determinations, that women would be less capable of producing science and technology [5]. One of the problems that arises is that the university will lose its revenues if this is done. However, the reality of the Coronavirus showed that the University preferred to decrease the number of students per class. But our research shows that, at the end of the course, almost 10% of students drop out for a variety of reasons. In this case, when creating classes of 25 to 30 students, the university will be rowing in the tide that can lead to unsustainability. For this reason, we suggest increasing the number of post-employment courses, taking into account first that they drop out along the way and, second, because this increase will compensate for the losses that scholarship students can cause to the university. In other words, the university will not spend anything in monetary terms with these students, whose responsibility will be borne by the parents. The university will simply have the mission of offering the learning space. The creation of a few numbers of students per class based on COVID 19 does not seem to be a sustainable idea. Epidemics and endemics are fleeting, as history proves [9] and science is there for that [10]. So, we have to think positively that this disease will pass as well as the others or we will have to learn to live with it because of what our decisions on institutional sustainability should be.

FEATURING THE GIRLS OF UNI ROVUMA

Field study data in Morupule district places the combatants’ daughters and descendants as one of the most excluded social strata in society. In addition to suffering all kinds of stereotypes and stigmas because their parents went to fight to liberate their country, these daughters do not find opportunities to study at the most advanced levels of education and, consequently, do not have access to the job market. Additionally, the daughters of combatants tend to have more children (on average 6 children) which has the immediate consequence of the inability to be able to educate them all; the land on which they practice agriculture tends to be increasingly reduced and women’s reproductive health tends to deteriorate. Meanwhile, the desire of combatants is to see their descendants trained academically in order to reduce poverty rates. In this sense, Rovuma University can play a leading role in the emancipation of women through higher education because its internal data shows that less than 40 percent is made up of female students. As the number of teachers and technical-administrative staff is under 20 and 15 percent, respectively, this university can also employ more women in order to deal with specific problems that only the female world can understand. In fact, from the carried study, the result is that at least 9.6% of girls drop out during the course due to various reasons such as sexual harassment, corruption, stigma, pregnancy, etc. Some of these reasons also interfere with the academic performance of girls who study at this University. In addition, more than 70% of women are included in the social and educational sciences, with the exclusion of them in the technical sciences, which is worrying.

MURRUPULA’S WOMEN UNDER POVERTY

The reasons for wealth and poverty between countries or between people, that is, why some countries and people are rich in relation to others, are obviously quite complex and, since before Adam Smith, many economists around the world have tried to understand them. And in the end, we continually ask ourselves: why are we richer or poorer than our neighbors? When we read the works of [11-13] we find some of the justifications for this collective national failure. If some think that the reasons for this must be inserted in the context of the African failure, others adopt the opposite view, considering that the independence of countries like Mozambique has given its citizens the possibility to choose their own economic trajectory to be pursued collectively. Regarding the factors of the Mozambican backwardness itself, obviously, several hypotheses were raised: Mozambique is poor because of its geographical location; colonialism; bad leaders; corruption, black race, idleness culture, lack of discipline at work, Mozambique is poor because of this or for that [14]. Some of these arguments find logical support when the dominant elite that defends the value of independence, self-esteem and the promotion of national products goes abroad to receive medical assistance, school for their children, products for domestic use, etc., while national hospitals do not have medicines, border facilities are devoid of toilets, schools with the usual problems and national farmers give up due to unfair competition from cheaper products from abroad. There is an inductive reasoning to be done when we look at the miserable lives of the former freedom fighters, today excluded from the benefits of their struggle, one of which is education. They did not study because they were struggling and their descendants are not studying because their parents did not study. Murrupula’s women as a whole and the daughters of former combatants in particular live in chronic poverty. Until they receive studies, their poverty cannot be expected to become temporary, that is, short-term or periodic poverty. As is well known, this occurs as a result of periodic fluctuations in people’s living standards and well-being levels. But these people have no expectations for the best. Temporary poverty results from factors such as financial crises, natural disasters, seasonal and temporary unemployment, high inflation and external shocks. Based on the fact that the duration of poverty is an important indicator, the definition of “chronic poverty is not only a lack of economic rights, but also long-term violent poverty that is passed down from generation to generation. The most important feature of the former combatants’ daughters in Murrupula is that they have a very low chance of breaking this cycle and getting out from poverty, their poverty is chronic, it persists for a long time in people’s lives and it is transmitted mainly to their children.

SOME BARRIERS TO GIRLS’ PROGRESS

If for girls from middle class families studying at higher level is a greater challenge, for those from poor families, this is an insurmountable obstacle. Firstly, the evaluation system that gives access to higher education is done without taking into account the local realities of the country. In other words, the University’s entrance exam only favors those who live in urban centers where there are means of communication, technology and libraries for consolidating reading. In rural areas, where 68% of the Mozambican population lives, there are no facilitating learning means other than those made available in the classroom by teachers in the respective courses. The amounts paid for enrollments to the entrance exam are another obstacle, because the parents and guardians are not sure if their relatives will be approved or not. This situation means that many girls who are dependent on their parents and guardians do not compete for the entrance exam, even if they have the desire to do so. Secondly, once at the University, evaluation methods that do not take into account the women’s particularities prevent them from continuing their studies by giving up from studies under subtle justifications.

Associated with these evaluation methods, most girls are enrolled in the social sciences because, for most of them, the technic sciences are not for them [5]. In a country where premature marriages prevail, many girls who enter University are either married or engaged for marriage. In Mozambican society, the power of men as a determinant of women’s conduct remains present. This causes girls to be overwhelmed and to do other domestic tasks or to dedicate themselves more to the desire of their partners, which interferes in their didactic contents learning. In the period when they are menstruating or pregnant, for example, it is normal to lose evaluation but teachers do not take into account that these conditions are exclusively biological over which the girls do not have the power to control them. Since the time that the Pedagogical University had its headquarters in Maputo, a policy that included women in education in general and higher education in particular has lacked clarity. What women have achieved so far is the result of an awakening either of themselves or their parents and never of a coordinated institutional policy for their inclusion. Now that the rectory is in Nampula and with a clear vision of what can be done in favor of girls, it is time for the university’s board of directors to rethink what can be done to materialize this. In proposing these measures, we are aware of the unfavorable arguments that will take refuge in the law itself. Legalists will say that women cannot have the privilege of accessing higher education while defending gender equality because the measure will be very unfair to men. We can answer in advance that the woman has long been a victim of the invisible exclusion that begins in the family and extends through the community and into the countryside, so the time has come to help her break free. If the woman comes to study at the university, she will be free from traditional obligations, such as overwork at home, marriage, poverty and ignorance of her reproductive social rights. And because she will be married later, she will have fewer children who will be able to give them an education which cut the poverty line in which they perpetually live. Some will try to see in this proposal an affront to sexism that dominates Mozambican legislation. We will say that everything that man has conceived can be modified and we must make changes as long as we have opportunities. Some make revolutions just for fear of the revolution itself, while others give gas for the revolution to happen regardless of its real and imaginary consequences. Others still do nothing more for the change because they have accommodated themselves in the wages that their position as institutional decision maker provides.

POVERTY AMONG FREEDOM FIGHTER IN MURRUPULA: A PROBLEM WITH DIFFERENT APPROACHES

Poverty can vary according to the country, region, gender, political regime and culture. According to the relevant literature, two basic approaches are used when examining their causes. The first approach argues that poverty is caused by socioeconomic and structural problems in each country, region or community. Talking about socioeconomic and structural reasons is the same as talking about the unequal distribution of income between countries, regions or communities, inadequate spending on savings, barriers to investment, poor education and health and ineffective social security. Among the effective factors in their implementation are the economic policies implemented by the day’s regimes against the will of the poor, the unequal opportunities to citizens and the insufficient labor markets to attend the economically active population. The second approach focuses on personal and collective skills, collective determination to overcome obstacles, discipline in the workplace, decisions made in search of opportunity and even luck. These two approaches are not exclusive, but complementary in themselves [15]. The socioeconomic and structural problems point to the macro causes of poverty, while the situations of individuals and groups refer to micro causes. It has been accepted that the macro causes of poverty derive from events that have a wide variety of effects that occur outside the individual, society or country’s characteristics, while the micro causes are due to the individual and the family sociodemographic characteristics (education, gender, religion, political-party relationship, etc.) as well as the personal decisions (migration, investment, etc.). Poverty has a female face in Murrupula. The simple observation of a couple going to or leaving the machamba in the street can attest to this. For example, if a man has slippers, his partner will certainly walk barefoot. This fact is repeated when we look at the daughters of freedom fighters. Poverty is an indelible mark on their faces. The concept of “the feminization of poverty” was first used by Diane Pearce in 1978. Pearce used this concept to draw attention to the fact that women constituted 2/3 of the poor in America in those years and the economic position of women deteriorated between 1950 and 1970, despite the increase in the female labor force participation rate over time. Many studies have also revealed that the number of poor women is excessively greater than the number of poor men and that poverty is experienced differently by men and women. In 1995, the term “Feminization of Poverty” was included in the Plan of Action of the 4th World Conference on Women [16]. The lack of a common definition of poverty that is agreed upon by different disciplines and different schools of thought, and the existence of very different approaches to the causes, consequences and ways of dealing with poverty have made this concept extremely controversial. Furthermore, the basic emphasis of the concept of poverty has changed with the effect of paradigms that have dominated in different periods, especially from the industrial revolution to the present. Dozens of different definitions of poverty were made, sometimes focusing on work, sometimes on development and growth, sometimes on consumption. Thus, poverty has become a magical tool that can cover up different contradictions in each period. For example, today it has become a general trend to look for solutions to poverty rather than examining class contradictions and the consequences of neoliberal policies. The reason why the masses with different social positions share poverty is, without a doubt, the appropriation of the means of production by the propertied classes, if we believe what the Marxists claim. However, the abundance of women among these poor masses and the differentiation of their experiences of poverty cannot be understood without including the patriarchal system in the analysis. Although Murrupula lives the matrilineal kinship system, women’s poverty is a result of the unequal pattern of socially sanctioned gender roles. Although different definitions of poverty have been made and poverty has different content according to theoretical contexts, it seems that basically all definitions are based on the lack of access to basic income and the resources necessary for human life. The clear relationship between women’s inability to access resources and income on equal terms with men, their unequal participation in the control of property and income, the devaluation of their work and the feminization of poverty as a whole make family inequality invisible. The data revealed that although women account for 40% of employment worldwide, they make up 60% of the working poor. Women cannot access the labor market at the same rate as men, in equal position and with equal pay. The restructuring and deregulation of labor markets has exacerbated this inequality. This situation significantly increases the proportion of women among the working poor. The characteristics of patience, meekness and obedience attributed to women lead them to concentrate in unskilled, low-paid, labor-intensive, routine, boring, attention-demanding, dexterous jobs. In accordance with gender roles, jobs that require a smiling face, dexterity, sexual attraction, jobs related to social issues or education, care and cleaning jobs, which are seen as an extension of women’s home responsibilities outside the home, are mostly women’s jobs. Due to discrimination in the labor market, while some high-paying and high-skilled jobs are closed to women, the inability of women to receive equal pay for work of equal value, their working in part-time, low-status and informal jobs, and the low level of unionization are the reflections of their secondary position in the labor market. In Murrupula, the fact that women are excluded from the labor market, that is, they do not have the opportunity to earn an income of their own, is the main determinant of women’s poverty. While female labor force participation rates are increasing throughout the country, this rate tends to decrease in Murrupula. Neo-liberal agricultural policies have led to the elimination of small producers and a continuous decline in agricultural production areas and the number of animals. The wave of immigration to the city, which manifested itself as a result of this transformation, results in the fact that women who previously participated in agricultural employment cannot easily access employment opportunities in the city and are condemned to two options such as being a housewife or working in informal jobs in the city. While the labor force participation rate in the country is 20.2% for women, it is 62.4% for men and 79.8% of the employed population is men. Undoubtedly, the patriarchal mentality, which sees women’s place as their home, plays the biggest role in this matter. The “housewife” responsibilities imposed on women, especially in care services, constitute an obstacle for many women to participate in employment. Despite the disintegration of the extended family structure in which care services are divided among the women in the household, free and qualified care opportunities are not created in Murrupula. Pedro and Tosun [4] in their research on poverty, pointed out that very few of the poor women work for wages, and the main reason for this is the care of their many young children.

HISTORICAL AND SOCIO-CULTURAL REASONS FOR POVERTY

Even when the government is trying to advance its country, the cultural environment can impede development. Then there are the prejudices against technique and progress, flight from the wealthier classes from industrial and commercial activities (which they consider to be unworthy and unworthy), permanent feudal system, strongly patriarchal family structure, landowning or mini-land ownership, prejudices related to transmission land ownership, etc. Society’s religious or cultural norms can prevent women, for example, from having economic or political rights and leaving them uneducated, thereby impeding their contribution to general development. Rejecting women’s rights and education results in cascading problems. Perhaps most importantly, the demographic transition from high to low fertility is delayed or completely avoided [14]. Poor families continue to have six or seven children, because they primarily consider the role of women to be procreative; and lack of education means that they have little choice as a workforce. In these settings, women generally lack basic economic security and legal rights; when they become widows, their social conditions worsen and remain in complete poverty, with no hope of recovery. Social norms can prevent certain groups from gaining access to public services (such as school, health and education). These minorities may have blocked access to universities or jobs in the public sector. They can be subjected to harassment in the community, including boycotting their jobs and physically destroying their property. In extreme cases, massive “ethnic cleansing” can occur. A diffuse illusion, supported by the advocates of globalization, is that the remaining problems of misery will take care of themselves because economic development will spread everywhere. In other words, the forces of globalization are strong enough for everyone to benefit, as long as they behave well. In real geographic terms, the rising tide of globalization has raised many economies that are on the water’s edge. They are societies that literally have boats on the water. The free trade zones that drove the beginning of industrialization in Asia, for example, were all located on the coast. But a rising tide does not reach the high mountains of the Andes or the interior of Asia or Africa. Market forces, no matter how powerful, have identifiable limitations, including those imposed by adverse geography. Even worse, when economic progress does not reach a country, economic conditions may worsen, as population growth and depreciation of capital (including depreciation of natural capital) lead to decreasing proportions of capital per person. In the African case, there are more children per family. Places with high infant mortality also show high population growth, contrary to popular belief. Fertility rates decrease as the economy develops. The more children survive, the less likely families are to have more children confident that each is much more likely to survive. And as families are moving from subsistence agriculture to commercial agriculture and, in particular, to urban life, they also prefer to have fewer children. This is partly due to the fact that children are no longer as valuable as agricultural work. When families receive modern amenities, such as water near the house, or a stove that uses gas in cylinders instead of firewood, children no longer need to bring water and firewood. When families send their children to school, the costs of raising them increase. The families then decide to have fewer children in order to invest more in each one. When mothers find the best economic opportunities outside the home and outside the field, the time spent raising children also increases. And, of course, when families have access to modern medical services, including family planning and modern contraceptives, they can fulfill their new desires regarding family size. All of these factors explain why, in most countries in the world, there has been a notable decrease in the overall birth rate and a sharp slowdown in population growth. This phenomenon has not yet reached Murrupula, where favorable conditions have not yet been created - children’s survival, girls’ education, employment opportunities for women, access to water and modern cooking fuel and planning and contraception familiar. The investments to end suffering in Murrupula are exactly the same as those that will lead to a rapid and decisive decline in fertility in a short period. For Murrupula’s people, there is a hypothesis that the likelihood of being poor increases as the number of children in the family increases. Low-income families tend to have more children to secure their future and are unable to break free from the poverty chain. Some of the poor families may prefer to get a job for their child at an early age, rather than paying attention to their children’s education. However, families with high incomes keep the number of children low in order to provide a better education for all of them. While the poverty rate is 9.65% in families where 3-4 people live, it is 40% in families with 7 or more people. However, the risk of poverty can be exacerbated in single-parent families and in families with people with disabilities in their homes. Having only one adult to care for children and the elderly in the family can lead to low income and poverty in the family. While the poverty rate is 15.98% in nuclear families with children, this rate increases to 19.2% in single-parent families and to 24.4% in large (patriarchal) extended families. Having a disability in the family can mean that at least one of the family members takes care of the person with a disability, does not work, and does not receive income for that work. On the other hand, expenses for the care of the disabled can make the household reduce other expenses, such as education and health, and exacerbate their poverty.

BARRIERS TO STUDY AT ROVUMA UNIVERSITY

To study at the Rovuma University, admission is done through the entrance exam, which is carried out throughout the national territory. For each course there is a target for the number of students required and their selection is made according to the grade obtained in the entrance exam. This causes some University candidates to fail, even if they have obtained a positive grade, since the required number of students is complete. As we have already said elsewhere, if this model does not meet the reality of the country, the entrance exam does not guarantee quality because it is a mere administrative means of selection and exclusion, with girls being the most affected because their scores are often low. However, the examples show that students who admit with high grades often do not always perform satisfactorily once at university, while those who enter with low grades perform above average. For girls there is an additional factor. The entrance exam is done during the holidays, when they have little freedom to leave the house. During this time, parents who live in rural areas burden girls with household chores. Unlike boys who, in addition to having little housework, may rebel from their parents to prepare for the entrance exam, girls submit because their departure is always suspicious. It is clearly seen here that the exclusion of girls from higher education begins long before she thinks about going to university because the evaluation method favors more candidates who live in cities, since there are some means of learning there, while those who live in the countryside, their passage depends much more on luck. It is clear that the entrance exam is not the only admission criterion, with some specific agreements that allow the entry of other privileged groups. However, there are no statistics to illustrate the extent to which bilateral agreements contribute to the admission of underprivileged girls to the University. At the University, the main problems for women do not happen during learning but in the days of taking tests. To assess the veracity of the information, we tried to talk to the girls who failed in some subjects, in order to explain the reasons for that failure. Data in our possession show that 80% of them failed because on the day of the test they were not in a position to do so claiming health problems. The relevant question would be why were they sick only at the time of the test? Their responses varied: 8 percent felt bad about the pregnancy; 26% had cramps and still preferred to be tested, 35% were menstruating; 14% had felt harassed by the respective teacher and 17% were late from college for some reason related to domestic work and the care of the partner. As we can see, all these obstacles concern the biological conditions of women, but they are never taken into account by teachers. Studies show that the scarcity in the supply of professionals trained in disciplines related to Exact Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics can weaken a society’s innovation potential. Although there has been an increase in female students in higher education in recent years, there is an untapped potential of women in these fields of knowledge. This untapped potential represents an important missed opportunity not only for women themselves, but also for society as a whole [17]. There are women who choose not to graduate in these areas or who decide to change careers because of obstacles, real or imagined. These obstacles can be found at the place of residence, at school or even at the workplace. Obstacles to women’s careers deprive societies of qualified human resources, which is detrimental to the competitiveness and development of society. In all societies, the causes of women’s failure in higher education require further study [18]. In fact, if identifying the causes and roots of gender disparities in these fields of knowledge is in itself difficult, developing an appropriate policy response to address the identified gaps is a major problem. In developing countries like Mozambique, most of the literature on gender inequalities in technical and political sciences designed to correct them is less than desired. The lack of information has prevented researchers from deepening the understanding of the reasons for this gap, which, in turn, prevents policymakers from developing effective interventions. There are hypotheses and factors presented in the literature to explain inequalities in recruitment, retention and promotion in women’s studies and careers, and some countries have already implemented more important policies that have contributed to a better gender balance in the areas under consideration [17]. A complete understanding of the factors that limit the career path of women in technical sciences has often been hampered by the persistence of several myths and clichés [5]. Some people argue that women lack the ability and drive to succeed in technical areas. However, studies of brain structure and function, hormonal modulation, human cognitive development and human evolution found no significant biological difference in the performance capacity of men and women in the natural sciences and mathematics [19]. Others argue that the problem of underrepresentation in colleges of inexact science will naturally be resolved over time. Others still think that the academy is a meritocracy. Although scientists like to believe that they “made a good choice” based on objective criteria, decisions are influenced by factors that have nothing to do with the quality of the person or work being evaluated. Such factors include prejudices about race, sex, geographic location of a university, age, etc. [17]. Another group thinks that changing the rules for selection, admission and promotion to promote gender equality means that standards of excellence will be adversely affected. Female teachers are less productive than male teachers. The publishing productivity of science and engineering teachers has increased over the past 30 years and is now comparable to that of men. The critical factor affecting the publication’s productivity is access to institutional resources. Marriage, children and caring for the elderly have minimal effects. In many institutes, women are members of low-power committees, have fewer financial resources, less staff support, or are located in more distant offices, do not have access to networks of beginners to obtain information, and do not have models or mentors to ask for advice. Women are more interested in the family than in the career. Many women scientists and engineers persist in their pursuit of academic careers, despite serious conflicts between their roles as parents and scientists and engineers. These efforts, however, are often not recognized as representing the high level of dedication to the careers they truly represent. Women take more time off due to child rearing, so they are a bad investment. On average, women take more time off at the start of their careers to fulfill their caring responsibilities. But in middle age, a man is likely to take more sick leave than a woman. The system as it currently exists has worked well in the production of great science; why change that? Career impediments based on gender, racial or ethnic prejudice deprive the nation of talented and accomplished researchers [17]. Throughout history, problems with women’s education have been at the top of the list in almost all countries [20]. Although the first interaction with the technical sciences and mathematics occurs in elementary and high school, higher education is the critical stage in which students decide their future careers. The transition from high school to higher education is identified as the point at which the highest proportion of students leaves the trajectory of technical and technological science and the exit rates of women far exceed those of men. That is why we believe it is relevant to train teachers to give pedagogical advice to students in secondary education, in order to encourage women to follow the exact sciences at the higher level. At the same time, women seem less inclined than men to choose a technical subject at the end of high school. Although the participation of women in general in higher education has increased worldwide in recent decades, increases in the enrollment rate in higher education have been concentrated in areas where female participation was already high [5]. But female representation in technical disciplines remains low, due to several causes. The literature indicates that preferences, motives, values, stereotypes and cultural norms can explain this situation. However, the decision to follow a certain higher education level course (and choose it as a career) is strongly influenced by the experience of previous levels of education. Students’ plans for their education and future careers are influenced by their expectations of their social role. The expected roles and responsibilities of the family play a central role in future planning and influence the expectations of individuals. Women prefer careers that do not conflict with family responsibilities and are useful for raising children, such as education, psychology or medicine. Therefore, it seems that women do not consider the technical fields suitable for the family. In addition, it may be more difficult to combine family and work in some fields (for example, those that require many hours of laboratory work) than in other fields (for example, social sciences). Other authors note that women are attracted to fields more related to people than to numbers. Empirical evidence suggests that young men make their choices primarily based on their career prospects, while women are also motivated by social and / or political commitments [17]. Stereotypes have functioned as ideological and social barriers that prevent women from significantly impacting these professions. Stereotypes discourage women from careers in technical fields because many believe that these fields are more related to male than female characteristics. Family background and the absence of female models can also influence women’s participation in technical careers. It is for this reason that we suggest the return of women who would benefit from scholarships to their areas of origin in order to serve as a model. Young people make career choices based on the experiences of adult workers. When women become successful in one area, the next generation is more likely to emulate their success. In addition, a woman’s family can influence her choice of field of study. In developed countries, engineering students and other branches of science generally have at least one parent with a profession in one of these disciplines. Since men tend to overestimate their mathematical competence in relation to women, men are also more likely to pursue activities that will lead them to a career in science, mathematics and engineering. This clearly points to the importance of having a female model working in a profession or study area dominated by men. In male-dominated areas - such as techniques - cultural norms are a key factor in explaining the low participation of women [17]. In higher education, women may encounter a cold climate, face harassment and have difficulty in socializing with teachers who are mostly male. If women are having more negative experiences than men, they may be more inclined to leave. Cultural norms and stereotypes can also affect women's access to accurate information, as well as their perceptions of technical careers. Many girls and their counselors are influenced by stereotypes that tell them that certain jobs are for men only. Popular knowledge of the costs and benefits of higher education is drastically out of step with reality and can be an obstacle to education. In addition, despite high aspirations among ethnic minorities and women, these groups have misperceptions of future rewards in many of the key professions, effectively inhibiting them from choosing these careers.

CONCLUSION

This article aimed to propose measures that UniRovuma can adopt to increase the number of female students in higher education by focusing on a particular group, namely the Murrupula former freedom fighters' daughters. After consolidating this experience, the project is expected to be extended to other excluded social strata, so that more than a thousand girls will attend university by 2025, contributing to improving their reproductive and economic conditions. Many studies on the education of women emphasize that educating a woman means educating a family and is more important than educating a man. While it is known that women's education has positive contributions to society, it is known that little attention is paid to women's education, especially in developing countries [18]. The negative relationship between ignorance of women and the health of their own children was also mentioned, and it was stated that for these reasons girls and women should be educated and this was essential for the progress and happiness of Mozambican society. All of this shows that the education of girls and women in general is very important due to the social benefits that result from it. Women who study more get married later and have fewer children. As the woman's schooling increases, there are significant improvements in family health. Most importantly, infant and child deaths are inversely related to women's education. With the education of women, the use of contraceptive methods becomes widespread and this helps the family to reach the desired size. All of these additional positive effects of a woman's education not only improve the well-being of her and her family, but also greatly enhance the well-being of the entire society.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Genetics and Cell Biology (ISSN:2639-3360)

- Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine (ISSN:2641-6948)

- Proteomics and Bioinformatics (ISSN:2641-7561)

- Journal of Astronomy and Space Research

- Journal of Agriculture and Forest Meteorology Research (ISSN:2642-0449)

- Food and Nutrition-Current Research (ISSN:2638-1095)

- Advances in Nanomedicine and Nanotechnology Research (ISSN: 2688-5476)