5221

Views & Citations4221

Likes & Shares

MASLD diagnosis is associated with presence of chronic gut conditions

An epidemiological projection is expecting an increase of IBS incidence, with estimated ~120 million people living with this condition between years 2020 and 2040 worldwide [8]. Evidence to date indicate that degree, as well as diagnosis of MASLD might be etiologically associated with occurrence of IBS, showing that MASLD can increase risk of developing IBS in the long-term manner. A study conducted on data gathered in the UK Biobank from total of 396,838 participants aged between 37 and 73 years of age from England, Wales and Scotland, of which 153,203 (38.6%) had prior diagnosis of MASLD (fatty-liver index, FLI ≥ 60) demonstrated that the individuals with liver disease have 13% IBS (HR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.05-1.17) higher risk of developing IBS in the perspective of 12.4-year follow-up. Furthermore, lean patients with MASLD had 22% increase risk of IBS incident; whereas in obese individuals with MASLD this increase was 9%. Further analysis indicated that the increased risk of IBS was with FLI quartiles across age, gender, alcohol consumption, and smoking subgroups, except for males aged ≥ 65 years and previous alcohol drinking [9]. Interestingly, observed gender-specific difference in the positive association between MASLD and IBS in females (but not in males) still needs to be investigated, there is possibility that reported disturbance in the signaling within trace aminergic system caused by female reproductive hormones, may alter colonic physiology, affecting ion secretion, immune responses and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) levels, thereby leading to the gut microbiome imbalances, and mucosal immunity, which were implicated as etiological factors in IBS pathogenesis [10]. Noteworthy, MASLD patients with IBS-like symptoms may also have the increased rate of psychiatric symptoms, which may additionally impact on quality of life and response to therapy. A cross-sectional study of 130 patients, with 38 satisfied Rome IV criteria for IBS (IBS group) versus 92 who did not (non-IBS group) indicated the increased prevalence of depression (18.4% vs 5.4%, P=0.01) and anxiety (31.6% vs 9.8%, P=0.002) in those affected by IBS group. A gender (female), prior depression, and obesity (body mass index (BMI)>30) were independent predictors of IBS in MASLD. Interestingly, newly diagnosed IBS patients, had lover levels of liver biomarker gamma-glutamyl transferase (67.5 vs 28, P=0.04), and increased abdominal pain which was associated with the change in stool frequency [11]. MASLD is a common concomitant condition in patients with IBD with increased prevalence trend. A meta-analysis carried out in total1,387,184 people with IBD from 27 different countries, indicated that the total global prevalence of NAFLD in IBD patients is 24.4% (95% CI, 19.3-9.8; I2 = 99.7%), including 20.2% (95%CI, 18.3-22.3; I2 = 99.7) in individuals with CD and 18.5% (95%CI, 16.4-20.8; I2 = 99.5%) in those with UC. Interestingly, Europe and America had the highest MASLD prevalence, being 43.1% (95%CI, 34.3-52.1; I2 = 92.3) and 35.7% (95%CI, 30.1-41.5), respectively. In contrast the lower prevalence was reported in IBD patients from South Asia, 19.7% (95%CI, 10.8-30.4) and in the western Pacific region 18.7% (95%CI, 12.2-26.2; I2 = 90.7). This prevalence in males had higher trend for both UC and CD, compared to females. Further analysis including diagnostic stratification of MASLD patients according to the liver fibrosis assessment tool, indicated that liver fibrosis was present in 23.6% of patients with IBD. Although special cautious should be taken when interpreting the results, as diagnostic methods vary widely between studies, it seems that almost one-quarter of patients with IBD might present with NAFLD worldwide [6]. Despite the well-established association between MASLD and obesity, there is also increasing evidence on the development of MASLD in lean individuals, who are also affected by significant risk of developing liver fibrosis, especially if they were diagnosed with IBD. A cross-sectional, case-control study conducted on 300 lean cases with IBD and 80 lean controls without IBD, indicated that lean individuals with IBD have a significantly higher prevalence of MASLD compared with lean non-IBD group (21.3% vs 10%; P = .022), nevertheless with no differences in the prevalence of significant liver fibrosis (4.7% vs 0.0%; P = 1.000). Interestingly, in this cohort, there was also no differences between the prevalence of MASLD in IBD and non-IBD participants who were overweight/obese (66.8% vs 70.8%; P = .442). Noteworthy, the overweight/obese IBD patients when compared with the lean IBD group have significantly higher prevalence of MASLD (P < .001). In this study, IBD diagnosis was an independent risk factor for MASLD in lean participants (odds ratio [OR], 2.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05-7.01; P = .04), when considering metabolic risk factors and prior history of steroid use. Furthermore, the overweight/obese IBD patients with MASLD compared to lean individuals showed higher levels of the insulin resistance and had history of smoking [12].

Role of gut microbiota in MASLD development: implications for gut inflammatory conditions

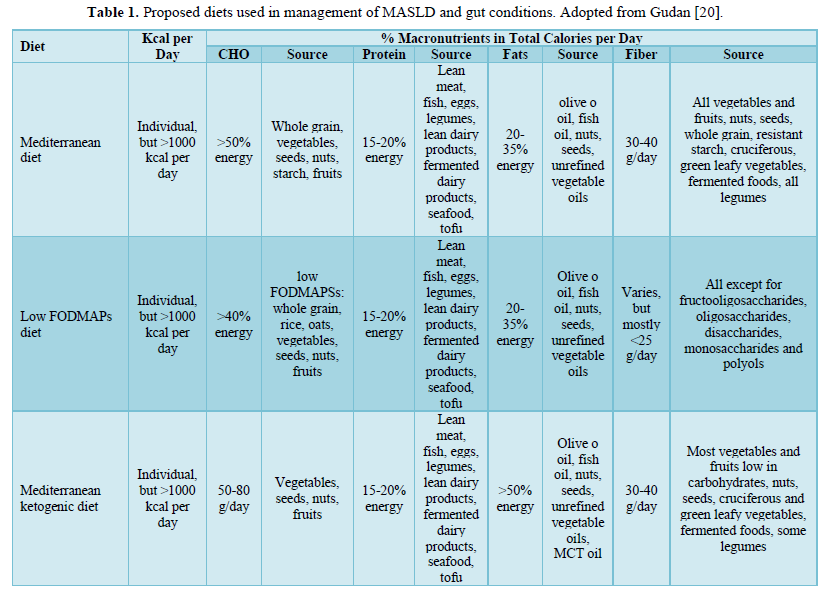

A recent epidemiological evidence demonstrates that MASLD can be also accompanied by presence of food allergies and inflammatory gut conditions, attributed to disturbances in lipid metabolism and gut microbiota composition. The reported co-existence of MASLD with allergic reactions to certain food and inflammatory gut diseases is of particular importance, as t highlights the potential for a shared pathogenesis involving gut dysbiosis, chronic inflammation, and metabolic disturbances. To date, studies have shown that the dysbiosis of gut microbiota plays role in the development of MASLD by modulating the fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, as well as by production of metabolites that affect liver function. Moreover, despite the increase in the incidence of IBD-related obesity, individuals with IBD and MASLD often displayed a lower mean BMI and lower type 2 diabetes prevalence, thus lean/nonobese patients should be carefully assessed, particularly in the context of IBD, as they have often is inadequate nutritional status due to malnutrition [13]. Disturbance of a bidirectional communication between liver and gut, referred as the gut–liver axis, promote development of hepatobiliary conditions, that could also be triggered by intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis [14]. Therefore, dysfunction of intestinal barriers along with increasing intestinal permeability increase transport of pro-inflammatory pathogen-associated molecular patterns and microbial metabolites via the portal vein, thereby allowing to enter the liver and promoting inflammation. This may explain why up to 30% of patients with IBD liver present with abnormal liver biochemical test results, with the hepatobiliary manifestations and steatotic liver, being responsible for up to 40% of the alterations diagnosed [15]. A Western-like diet characterized by excess of carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fatty acids, emulsifiers, or artificial sweeteners, as well other high-fat and high-fructose diets have been shown to trigger or deteriorate gut inflammation and increase intestinal permeability ultimately leading to microbial dysbiosis and leaky gut syndrome which all together have been implicated in obesity and chronic inflammatory disease [16]. Although current guidelines strongly advocate to follow a Mediterranean diet in patients with IBD and MASLD, as this diet by promoting the consumption of unprocessed locally sourced foods, including wholegrains, fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, fish, and olive oil has been shown to reduce inflammation and hepatic steatosis, as well as risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver disease-related death [17]. Furthermore, the adherence to traditional Mediterranean diet has been linked to beneficial gut microbiota modifications associated with clinical remission maintenance in UC and lower risk of CD [15]. Interestingly, changes in gut microbiota composition in MASLD patients, which can result in higher gut permeability, allowing substances to pass through the intestinal barrier more easily, thereby leading to translocation of proinflammatory mediators/toxicants, which can further affect liver, potentially contributing to the progression of liver disease. Studies have shown that MASLD patients exhibit higher levels of liver biomarkers (AST, GGT), as well as cholesterol, and albumin compared to healthy controls, along with a higher prevalence of comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis [18]. Additionally, this reported increased intestinal permeability common for IBD allergic responses to food with presence of malabsorption disorders and inadequate nutrient metabolism (vitamin B12, iron, choline fats, carbohydrates and proteins), may increase risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), especially in MASLD patients with comorbid obesity; therefore the low FODMAPs diet based on temporary elimination of strongly fermenting fructooligosaccharides, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, can be incorporated prior to the Mediterranean diet [19]. As by restoring gut homeostasis, can reduce abdominal symptoms and improve the quality of life. Nevertheless, the impact of low FODMAP on liver function still needs to be assessed [20] (Table 1).

CONCLUSION

The evidence linking food allergies and chronic gut conditions like IBD and IBS in individuals affected by MASLD is rapidly growing highlights the importance of personalized dietary management for these patients. Not surprisingly, identifying environmental and dietary factors leading to chronic activation of immune system, followed by alerted gut microbiota functioning may be crucial for managing both the gastrointestinal symptoms of IBD and potentially reducing the risk or progression of metabolic conditions, such as MASLD. The application of personalized adjuvant strategies includes 2 main approaches: promoting an increased adherence to a healthier eating pattern (eg, Mediterranean-like), and encouraging an increased total volume and intensity of physical activity. Liver specialist referral should not wait when there is suspicion of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis and moderate-to-severe hepatic fibrosis. Further research is needed to fully understand this complex relationship and its implications for the development of metabolic disorders in this patient population.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Cancer Science and Treatment (ISSN:2641-7472)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- Chemotherapy Research Journal (ISSN:2642-0236)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- Journal of Neurosurgery Imaging and Techniques (ISSN:2473-1943)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- Archive of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine (ISSN:2640-2297)