1108

Views & Citations108

Likes & Shares

Organ transplantation is the gold standard treatment of choice for many patients with organ failure and has undoubtedly improved both the quality and longevity of life for the majority of patients. The success of human organ transplantation relies on the willingness of the public to donate their organs, either during their lifetime or after death. In the United Kingdom (UK), transplantation is limited by a shortage of donated organs, especially in the South Asian community. This leads to a disproportionate number of Asians waiting for transplants longer than the average waiting time, as often, most suitable matches are found between people of the same ethnic group. This disparity costs lives, and many who are waiting count down their days on the list and lead an agonizing life due to the scarcity of matching organ donors.

This article is derived from a two phased study that sought to explore possible methods to increase the number of registered organ donors and cadaver organ retrieval in the South Asian community in the North West of England. A total of 907 participants completed the questionnaire and 10 semi structured interviews with individuals who declined to join the organ donor register were undertaken to understand the in-depth details of their negative attitude towards organ donation. This paper reflects on one of the focus areas of the study - the views of South Asians on the implementation of an opt-out system in the UK and to understand if the community will challenge or support such a donor recruitment method. This study was funded by the British Renal Society and supported by the Central Manchester Foundation Trust, University of Salford and National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT).

Keywords: South asian, Knowledge, Survey, Organ donation, Opt out, Opt in, Religion

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, there has been significant debate on whether the United Kingdom (UK) should change the current system of organ donation of ‘opt-in’ to ‘opt-out’ with presumed consent. Following the announcement from previous UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, in 2018 about her support to change the law in favor of presumed consent for organ donation, swift action has been taken by the UK Transplant field to see the opt-out law introduced on 20 May 2020. Historically, it has been noted that there is an urgent need to address the inferior and reducing rates of organ donation in the UK from Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) donors [1]. According to the NHSBT annual report 2019, total deceased Asian donors in the UK were only 56 (3.5% of total donors); despite a rapid increase in recipient numbers - i.e. 13% of recipients who received a deceased donor transplant during 2019 were Asian. On the waiting list, 16.8% who are registered as waiting for an organ transplant are Asian, from which 921 are registered for kidney transplantation alone [2].

BACKGROUND

In 2008, the UK Organ Donation Task Force (ODTF) investigated the potential impact of moving to an opt out system. They concluded that such a system would deliver real benefits but warned that there was potential to undermine the concept of donation as a gift and erode trust in National Health Service (NHS) professionals and the Government, thus potentially negatively impacting organ donation. Consequently, the ODTF advised not to introduce an opt out system in the UK in 2008. However, 12 years on and with the positive experience of dozens of lives saved in Wales since the adoption of an opt-out system in 2015 [3], it is important to revisit the opt-out option in the UK. In 2012/2013, consent in Wales was only 53.6%, but in 2018/2019 it increased to 77% following implementation of opt out law.

In our previous study [4] among South Asians in the UK, the need for re-addressing the idea was highlighted, as more than 50% of participants supported opt out implementation, especially as the UK’s organ donation consent remained poor when compared to other European countries (approximately 60% compared with over 80% in Spain). Reflecting on the report from NHSBT’s donor activity report 2019, opt out implementation needs to be re-addressed, particularly as the UK has one of the highest rates of family refusal in the Western world, even in the face of recorded wishes of their loved one; this is particularly prevalent among the BAME community [5].

This article is derived from a two phased study that seeks to explore methods to increase the number of registered organ donors and deceased donor organ retrieval in the South Asian community in the North West of England. A total of 907 participants completed the questionnaire; in addition, 10 participants who declined to join the organ donor register completed semi-structured interviews for a better understanding of the reasons for their negative attitude towards organ donation. This paper reflects on one of the areas investigated in the study - the views of the South Asian population on implementation of an opt out system in the UK and to understand if the community will challenge or support such a donor recruitment method.

Current practice in the UK for consent in organ donation

|

Presumed Consent - Opt Out |

|

Finland, Portugal, Austria, Sweden, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Poland, Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, Chile, Luxembourg, Argentina, Wales |

In the UK, an opt in or informed consent for organ donation is followed and normal practice is to obtain consent from a next of kin, even if the person is listed on the Organ Donor Register (ODR). Registration via an ODR (opt in) demonstrates a willingness of an individual when they are alive to donate organs in the event of their death [6]. If a person dies and did not carry a donor card or had not added their name to the NHS ODR, their nearest relative (next of kin) is asked to provide consent for their organ to be donated. The Human Tissue Act [7] and equivalent [8] explains clearly that a declared wish to donate organs (for example joining the

NHS ODR) should be regarded as authorization for organ removal following death and this should supersede any objections offered by the surviving family to proceed with organ donation. Even though this law is in place, the family’s consent remains a vital part in proceeding with organ donation in the NHS and it is rare to proceed in cases where an objection is made. This is an aspect of organ donation which requires further examination but is not within the scope of this paper.

It is important not to assume that a person does not wish to donate just because they are not listed on the ODR; it is possible they were supportive of donation but had missed or overlooked the opportunity to register this wish formally. It is also possible that an individual had recorded their wishes in a different way, maybe through a conversation with family and friends. However, there may be circumstances when wishes of the potential deceased donor cannot be determined. In these circumstances, the law allows for an individual’s next of kin to decide on their behalf. The Human Tissue Act [7] describes this action as giving ‘consent’ and the HTA Scotland (2006) describes it as ‘authorization’. Both provide a hierarchical list of qualifying relatives who may assist with such a decision. A next of kin can give consent but no conditions can be made by the donor or their family on organ allocation, which is stated under section 49 of the HTA (2006) [8].

What is Opt Out/Presumed Consent?

Presumed consent or ‘opt-out’ assumes consent from every potential deceased donor to proceed with organ donation, unless the deceased has expressed a wish in life not to be an organ donor [9,11]. This can be divided into what is known as a ‘hard opt out’ where the family is not consulted, or a ‘soft opt out’ when the family's wishes are considered in the same manner as with the current ‘opt-in’ system.

There are 14 European nations operating opt out or presumed consent systems introduced in the last 30 years [12] and in the UK, Wales adopted this in 2015 (Table 1). The introduction of opt out legislation in these countries has resulted in increased rates of deceased donors - more than 30 per million population (pmp) of kidney donors per annum [11]. This is also reflected in Wales’ organ donor report, the most recent statistics revealing a 72% consent rate and approximately 24.3 donors pmp, putting Wales at the top of the list in the UK (55 deceased organ donors in the first three quarters of 2017/18, 16 more than the same period in the previous year [13].

ETHICAL DILEMMA: FAMILY’S CONSENT FOR DONATION

In organ donation, one of the most debated ethical issues is the family’s role in making the donation decision for the potential donor who may or may not be listed on the organ donor register. Some argue that the needs of potential recipients, who suffer with organ failure and their families, are much greater than the needs of the deceased or their families [14-16] indeed, the family’s distress of patients who die waiting for an organ may override the distress that donor families would suffer [17]. However, transplant professionals remain concerned about negative publicity if they were to override the family’s wishes [18] Identified that some members of the general public are of the opinion that the doctor may not optimize clinical care to save a patient’s life if the medical team know they are listed on the organ donor register, as they may consider the patient as a potential donor.

When declaring death, it is necessary to ensure the wellbeing of the family and next of kin [19] to prevent grief turning to distress. Also, it is important for the medical team to provide ethical justification to the family when they consent for a donation decision [20]. Balancing the distress of consenting families with the obligation to those awaiting transplants is a dilemma for society. Indeed, who ‘owns’ deceased donor organs and who makes the decision regarding allocation are both issues which need clarification [21-23]. There is a general presumption that the Government holds the responsibility for allocation or disposal of donated organs, which is then delegated to the appropriate transplant team [24]. If we consider the body as property in the hope of increasing organ supply, we will be devaluing human life and the human bodies we seek to save [25]. Within transplantation, it is essential the public is reassured, and respecting and seeking family consent for organ donation is a way of ensuring this.

STUDY MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study [4] utilized mixed methodology, i.e. questionnaires and face to face interviews. The questionnaire was validated and used by Morgan et al. [26] to understand the general attitudes and knowledge of organ donation among ethnic groups in the UK [27,28]. Respondents were asked 25 multiple choice questions, and this paper reflects on one of those questions - views on opt out implementation. At community gatherings, a hard copy questionnaire was provided along with an invitation letter and information sheet; our access to these South Asian gatherings was opportunistic and focused on areas where large numbers of people from the local population could easily be contacted, such as community centers, religious sites and social event platforms. This article will use the terminology ‘South Asian’ to represent individuals from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (the most significant ethnic community in several urban locations in the UK [29,30].

Sample

The aim of the survey was to explore perceptions and attitudes towards organ donation, recruiting sufficient people for analysis across the three South Asian groups rather than providing a representative sample of the target population. According to a 2011 census report, the target population of South Asians in the North West was 293,700 [31] however, to gain the views of so many would be impossible in the time frame. Therefore, it was anticipated that a sample of more than 500 people would be feasible to recruit given the study’s six-month time frame, similar to Karim et al. [27]. In addition, in a previous smaller study exploring barriers to organ donation, the researcher recruited 100 participants across two community events [4] in a one-month period, hence a sample of 500 responses was considered to be a realistic target. Data was collected between April and October 2012, with 554 completed questionnaires returned and a further 353 questionnaires completed online for a total sample of 907 (181.4% of the target).

The study obtained ethical approval from a number of organizations: The National Research Ethics Committee, Central Manchester University Hospitals Foundation Trust (CMFT) Ethical Committee (employer of researcher), University of Salford Research Ethics Committee (where the researcher was a PhD student) and NHS Blood and Transplant (to access Organ Donor Register statistics).

The initial questionnaire survey data was entered into an electronic survey system (BRISTOL) either directly by the respondent using the online questionnaire or by the researcher from paper questionnaires. A statistician assisted with analysis using SPSS (version 20). Initially Chi-squared tests were used to test the existence of associations between outcomes and demographic characteristics, and between attitudes, knowledge and demographic characteristics. The perspectives of the target communities (Indian Hindu, Indian Christian, Indian Muslim, Pakistani Muslim, Bangladeshi Muslim and others including Sikh) were examined and characteristics explored according to age, gender and level of education (Table 2). However, the sample obtained was self-selected so it was difficult to identify how representative the respondents were of the communities they came from.

A significance level of p

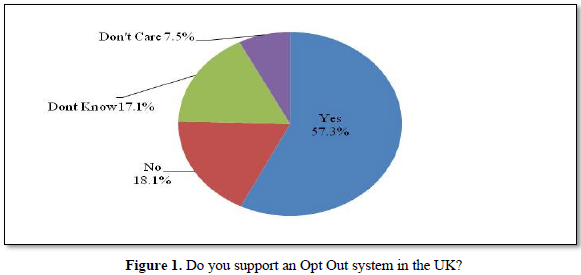

Perceptions of an opt out system

To ensure responses were reliable and participants understood the meaning of the questions, clarification was offered in the questionnaire. Respondents were informed that: ‘In some countries it is lawful to take kidneys from any adult who has just died, unless that person has specifically forbidden it while they were alive’, then asked whether they would oppose such an opt out system in the UK. Only 18.1% opposed such an idea and 57.3% were in favor of opt out. A further 24.6% were not sure or ambivalent (Figure 1).

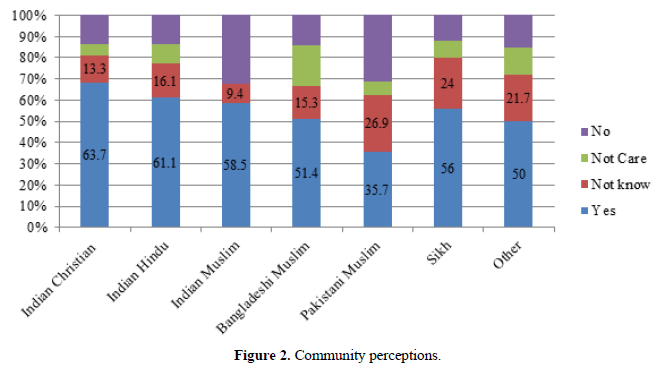

The Muslim ethnic communities appeared less in favor of such an approach, in comparison to other groups (Figure 2), particular the Pakistani Muslim community. Analysis of the different ethnic communities, rather than simple religious groups, identified differences that create barriers for some cultural groups and not others of the same religion – an important factor when providing education.

From the ten interview participants, only eight discussed opt out; five were unreceptive and opposed the idea. Their main concern was how the public will be informed about opt out registration if they did not wish to donate. All five participants who opposed the idea agreed that, if the whole community was educated on the topic, the opt out concept could possibly be implemented successfully.

A sample of comments and replies received from interview participants included:

‘I heard about it, it’s kind of like part of being on the register, still it bit serious commitment given that I am not still not sure about how I feel about. I would straight away opt out for two reasons. (1). For my beliefs (2). Another reason that’s too much control that the Government is having on my body and life to opt me in. To make that point I will straight away opt out. And if in case I change my mind I may opt in later. In that way I will have greater control over, I think that would help me to feel ease spiritually.’ (1FH)

‘I heard about it. It’s not fair; automatically you are getting organ donation system. Especially with the Asians they are very laid back and let it happen until the last minute and they will say I don’t want this anymore.’ (6MM)

‘I do not agree with it, because everybody not knows about it, due to the cultural and linguistic barriers not everybody knows that. Like my 70yr old grandma who has not many of her family members here, they are not aware so when she goes back, as she automatically opted in, she has been opened, no I do not agree with it. I do not think you will ever be able to raise the enough awareness for everybody to know that they have been opted in and they have to be opted out.”(8FM)

‘I am not very happy to hear about this, I did not know about this. I am not very happy to hear about it. There must be lot of people who have not heard about it. They might have not It is something you are forced into it. I wouldn’t agree with it.’(10FM)

Some respondents were receptive but wanted more information before they would make a decision:

‘I don’t know really. Well, I am 50:50. So for example, I don’t know how the system works out. If I am not sign up will they be able to take my organs, so if I opt out of it they may not. So, I don’t know, I never thought about. I might not object. Before, it was different, but now people believe in that.’(5FM)

‘I wouldn’t say it’s bad thing, from my own personal point, after the education and awareness people will have sufficient amount knowledge to decide whether they want to stay in Opt out or to remain inside the system for transplant. Otherwise if it’s no education and awareness then that person is already in the system and that person will start argument and then it will become extremely ugly.’(7MM)

Others agreed with the opt out concept, and after an opportunity to discuss their fears and perceptions, attitudes towards organ donation became more positive (note, this was supplementary to the original purpose of exploring why and what views were):

‘I agree with it, it depends people have different views. Even if it becomes a national law some people may be happy and some still not be happy. People may say why should we this is my own body I can do whatever I want. It shouldn’t be national thing; everyone should have their rights.’(9FM)

‘Only time will tell. I don’t think earlier on I would have opted out, but now with being aware of need and what you can do to a person after you dead and gone and if you can help somebody that’s what God want in this world. You are here to be a blessing if I am blessing even after my death yes, I will go for it and agree with opt out.’ (2FC)

Supporting evidence for opt out/presumed consent implementation

As the South Asian community in the UK is not responding to current organ donation campaigns [27], and perhaps not clearly understanding the severity and the susceptibility of CKD in BAME and the benefits of joining the ODR, it is vital to consider how to tackle this challenge. One solution could be to review and change the current policy of organ donation consent system in the UK [32,4]by implementing an opt out or presumed consent system.

The opt out system has been very strongly opposed by health professionals in the UK from the early 1900s, and there has been concerns on the disapproval from the BAME community [33]. In our previous study (2014), we suggested revisiting the opt out implementation as it was opposed by only 18% (57% said yes with the remainder stating no preference). This result is supported by Rithalia et al. [34] who conducted a systematic review on opt out opinion among the UK public. The review identified that, even though most people opposed an opt out system prior to 2000 in the UK, a further four studies revealed an average of 60% were in favour of donation by presumed consent.

Our study [4] noted that the proportion of participants who would agree to organ donation was 44%, more than double of those signed up to the ODR (17%). Several reasons for this exist, including perceived difficulty of signing up to the ODR, not knowing how to register, lack of information about what is required to join the register or that signing up is not a priority. Many of these issues could be overcome and this gap could be reduced by introducing an opt out system or automatic consent registration [35].

From the study sample, it is important to note that even the individuals (interview participants) who declined to join the ODR agreed with the implementation of an opt out system, if it is introduced after adequate education. Perhaps then, if the population and religious leaders are sufficiently educated on the benefits, an opt out/presumed consent system could be successfully implemented with public support [36-45].

CONCLUSION

It is important to recognize that initiatives in the UK to increase BAME organ donation to date have had limited success and evidence supports the notion that we need to discuss new ways of increasing the organ donation rate - one suggestion has been the implementation of an opt out system. There is clearly a need for further work to increase awareness of a consent system to increase organ donation rates and to clarify public concern on this topic. Awareness of an opt out system is not only a BAME issue - a study by Coad et al. [35] among young British adults identified that a minority of participants were aware of the proposed opt out system for organ donation [46-51].

There are no fundamental ethical or legal barriers to introducing soft presumed consent legislation in the UK. However, legal advice has suggested that a hard-presumed consent law would be open to challenge under the European Convention on Human Rights.

This article reflects on the positive attitude from the Asian community for the implementation of an opt out organ donation law and looks forward saving more lives in the UK.

1. Bramhall S (2011) Presumed consent for organ donation: A case against Annals of the Royal.

2. NHSBT (2019) Organ Donation and Transplant Activity report 2018/2019.

3. Welsh Government Report (2019) Wales leading on organ donation consent rates. Accessed via Wilkinson T M (2011) in press Ethics and the Acquisition of Organs. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

4. Pradeep A (2014) Increasing organ donation in the North West South Asian community through targeted education. Published Thesis University of Salford.

5. NHSBT (2019) NHSBT Board Meeting in Public - 31st January 2019. Available online at: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/15384/nhsbt-board-meeting-in-public-31st-january-2019-agenda.pdf

6. Mercer L (2013) Improving the rates of organ donation for transplantation. Nursing Standard 27: 35-40.

7. HTA (2004) Human Tissue Act.

8. HTA (2006) Human Tissue (Scotland) Act.

9. Kennedy I, Sells RA, Daar AS, Guttmann RD, Hoffenberg R, et al. (1998) The case for “presumed consent” in organ donation. Int Forum Transplant Ethics Lancet 2: 1650-1652.

10. Goh GB, Mok ZW, Mok ZR, Chang JP, Tan CK (2013) Organ donation: What else can be done besides legislature? Clinical Transplant 27: 659-664.

11. Kälble T, Alcaraz A, Budde K, Humke U, Karam G (2009) Guidelines on Renal Transplantation. Published by European Association of Urology.

12. ODTRP (2008) Organ Donation Teaching Resource Pack.

13. Welsh OD Report (2016) Welsh Government - Organ Donation Annual Report 2016.

14. Kamm FM (1993) Morality New York: Oxford University Press 1.

15. Harris J (2002) Law and regulation of retained organs: The ethical issues. Legal Stud 22: 527-549.

16. Harris J (2003) Organ procurement: Dead interests, living needs. J Med Ethics 29: 130-134.

17. Brazier M (2002) Retained organs: Ethics and humanity. Legal Stud 22: 550-569.

18. Siminoff LA, Gordon N, Hewlett J, Arnold RM (2001) Factors influencing families consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation. J Am Med Assoc 86: 71-77.

19. Rubenstein A, Cohen E, Jackson E (2006) The definition of death and the ethics of organ procurement from the deceased. Staff Discussion Paper.

20. Voo CT, Campbell VA, Castro DLD (2009) The ethics of organ transplantation: Shortages and strategies. Ann Acad Med 38: 359.

21. Andrews LB (1986) My body, my property. Hastings Centre Report 16: 28-38.

22. Kreis H (2005) The question of organ procurement: Beyond charity. NDT 20: 1303-1306.

23. Spital A, Taylor JS (2007) Routine recovery of deceased organs for transplantation: consistent, fair, and lifesaving. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 300-303.

24. Dossetor JB (1994) Kidney transplantation. Philadelphia WB Saunders, pp: 524-531.

25. Cohen E (2003) Organ transplantation: Ethical dilemmas and policy choices.

26. Morgan M, Hooper R, Mayblin M, Jones R (2006) Attitudes to kidney donation and registering as a donor among the ethnic groups in the UK. J Pub Health 28: 226-234.

27. Karim A, Jandu S, Sharif A (2013) A survey of South Asian attitudes to organ donation in the United Kingdom. Clin Transplant 27: 757-763.

28. Razaq S, Sajad M (2007) A cross-sectional study to investigate reasons for low organ donor rates amongst Muslims in Birmingham. J Law Health Ethics 4: 2.

29. Mather HM, Keen H (1985) The South all Diabetes Survey: Prevalence of known diabetes in Asians and Europeans. Brit Med J 291: 1081-1084.

30. Khunti K, Kumar S, Brodie J (2009) Diabetes UK and South Asian Health Foundation recommendations on diabetes research priorities for British South Asians. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Diabetes UK London.

31. ONS (2011) UK Census, Office for National Statistics.

32. Gauher ST, Khehar R, Rajput G, Hayat A, Bakshi B, et al. (2013) The factors that influence attitudes toward organ donation for transplantation among UK university students of Indian and Pakistani descent. Clin Transplant 27: 359-367.

33. Koffman G (2000) Personal communication to joint scientific commitee BTS 2000. Koffman G British Transplant Service Transplant Newsletter October 2000.

34. Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S, Norman G, Myers L, et al. (2009) Impact of presumed consent systems for deceased organ donation: A systematic review. Brit Med J 338: a3162.

35. Coad L, Carter N, Ling J (2013) Attitudes of young adults from the UK towards organ donation and transplantation. Transplant Res 2: 9.

36. Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C (2006) Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: Audit of intensive care records. BMJ 332: 1124-1127.

37. College of Surgeons of England (2011) May 93: 270-272.

38. Davis C, Randhawa G (2006) The influence of religion of organ donation among the Black Caribbean and Black African population: A pilot study in the UK. Ethnic Dis 16: 281-285.

39. Do H (2008) Department of Health, The Potential Impact of an Opt-out System for Organ.

40. Donation in the UK (2008) An independent report from the Organ Donation Taskforce, London.

41. Kälble T, Alcaraz A, Budde K, Humke U, Karam G (2009) Guidelines on Renal Transplantation. European Association of Urology.

42. Li D, Hawley Z, Schnier K (2013) Increasing organ donation via changes in the default choice or allocation rule. J Health Econ 32: 1117-1129.

43. NHSBT (2012) Saving lives together: Annual Report 2011-2012.

44. NHSBT (2013) TOT - 2020 Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020: A UK strategy. NHSBT publication.

45. NHSBT (2016) Annual Report 2015-2016.

46. NHSBT (2017) Annual Report 2016-2017.

47. NHSBT (2017) Organ Donation - Opt in or Opt out.

48. NHSBT (2014) Organ Donation and Transplant Activity Report 2013/2014.

49. ODTF (2008) Organ donation and task force, organs for transplants: A report from the Organ Donation Taskforce (2008) Department of Health.

50. Pradeep A (2010) An investigation into the reasons for the scarcity of deceased organ donors for renal transplant among migrant South Asians in the North West region of the United Kingdom. MSc Dissertation, University of Salford.

51. Welsh OD Report (2016) Welsh Government - Organ Donation Annual Report 2016.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Ophthalmology Clinics and Research (ISSN:2638-115X)

- Journal of Forensic Research and Criminal Investigation (ISSN: 2640-0846)

- Journal of Spine Diseases

- Dermatology Clinics and Research (ISSN:2380-5609)

- Journal of Clinical Trials and Research (ISSN:2637-7373)

- Journal of Cardiology and Diagnostics Research (ISSN:2639-4634)

- Journal of Renal Transplantation Science (ISSN:2640-0847)