1626

Views & Citations626

Likes & Shares

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) ranks third in United States veterans seeking psychiatric care through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Approximately 30% of the entire veteran population currently utilizes VA services leaving 70% to find care in the private sector or to go without care at all. The presence of PTSD among veterans is estimated at 35-40%. Unfortunately, current evidence-based treatment rates of remediation, including medication, are low, thereby necessitating the need for the development of more effective interventions. The challenge to the mental health service provider is to stay informed related to emerging treatments that offer the promise of alleviating PTSD symptomology. This article seeks to accomplish that objective. New innovative interventions are rapidly emerging, including Reconsolidation Enhancement by Stimulation of Emotional Triggers (RESET therapy) and Stellate Ganglion Block (SGB). SGB is alleged to inhibit connections between sensitized regions of the cerebral cortex and the peripheral sympathetic nervous system. RESET therapy is perceived to alter aberrant neuronal circuitry in PTSD sensitized regions of the brain through a unique sound, thereby resetting the altered circuitry back to a pre-trauma state. Both interventions offer a biologically-based approach to PTSD treatment. Psychologists and other adequately trained mental health professionals provide RESET therapy. Skilled anesthesiologists or interventional pain management physicians provide SGB. Both approaches serve to de-stigmatize the varied myths associated with PTSD. However, psychologists and other trained mental health providers are in a vital position to be able to implement a remedial intervention rapidly and non-invasively.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorder, Memory reconsolidation, Transformative treatment, Binaural beat, Stellate ganglion block

INTRODUCTION

As practicing psychologists trained over three decades ranging from the late 1960s to the early 90s, the authors have great empathy for the practicing mental health practitioner of the twenty-first century. The next generation of practitioners has assumed the mantle of responsibility for the timely and effective treatment of trauma-related disorders. The mental health profession is placed under immense pressure to deliver results quickly, safely and economically that meet the prevailing standard of care. The mental health client/patient of the 21st century has been saturated with pharmaceutical ads leading them to expect rapid relief within a brief period of time or within a handful of therapy sessions.

The current state-of-affairs in empirical and academic research on PTSD interventions presents the mental health clinician with bewilderment and little guidance as to which treatments are the most effective, tolerable, and cost-effective. The partisan and even acrimonious controversy between proponents vs. opponents of various theoretical/empirical camps is evidenced in some of the critical and meta-analytic published reviews of varied studies. Clinicians, in general, seek to avoid overly simplistic, iconoclastic or hopelessly biased analysis. The authors desire to provide valuable insights and guidance to collegial psychologist and other mental health practitioners who have had experience with ‘gold standard’ psycho-behavioral interventions in attempting to remediate the effects of PTSD.

The introduction of the practitioner to a promising and innovative recent treatment intervention called Reconsolidation Enhancement by Stimulation of Emotional Triggers (RESET therapy) is a primary objective of this article. The psychologist/clinician commands the front line related to applying breakthrough treatments that lead to the resolution and remediation of trauma-effects. Within this context, the authors commit to the relief of trauma-associated suffering to the fullest extent possible and further, to transform the afflicted individual to full potential and above all, to do no harm.

Shifting now to the issue of PTSD, the authors find that there is little remaining question that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is much more than a psychological problem, even though the current diagnosis of the condition is based solely on the presence of behavioral and psychological symptoms. Historically, the rendering of a mental diagnosis has fallen within the domain of the psychologist and psychiatrist.

PTSD AS A NEUROINFLAMMATORY CONDITION

Increasingly, cumulative evidence has identified associations between the immune and inflammatory systems and PTSD [1]. For those mental health practitioners who wish to maintain their involvement in this expanding perspective, it will require their ongoing awareness regarding the contribution that neuroscience is making related to clinical practice.

It is known that PTSD produces elevated rates of pro-inflammatory markers. Additionally, it is also thought to contribute to both the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of the ailment [2]. This reality becomes the challenge facing the mental health practitioner who has traditionally approached the issue primarily from a psychodynamic or cognitively-based point of view.

Acceptance of the above association provides support for the perspective that PTSD is more than a psychological problem but rather is a systemic disorder. The emergence of chronic medical conditions among those living with PTSD, as compared to those without it, has led to the exploration of a mechanistic link between PTSD and other comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD). An emerging body of evidence reveals that an immunological balance skewed toward a low-grade pro-inflammatory state (exists) in PTSD. It remains to be elucidated if inflammation precedes the onset of PTSD, identifying a vulnerable population, or rather ensures the onset of PTSD. Lastly, it is unclear how the time from index event, duration, and severity of PTSD symptoms might affect a potential relationship to inflammation. Other confounders include heterogeneity and chronicity of events leading to PTSD (war, childhood trauma, sexual assault, etc.) as well as temporal proximity to precipitating events [3].

The above awareness lays the foundation for the psychologist and other mental health providers increasing involvement as a source of first referral, rather than an option of last resort.

STATE OF CURRENT TREATMENT INTERVENTIONS

A 2018 consensus statement of the PTSD psychopharmacology working group advises that “there seems to be no visible horizon for advancements in medications that treat symptoms or enhance outcomes in persons with a diagnosis of PTSD” [4]. A follow-up letter by another group of researchers [5] comments that “With only 50% of veterans seeking care and a 40% recovery rate, current strategies will effectively reach no more than 20% of all veterans who need PTSD treatment.” In other words, psychologists are in an ideal position to rapidly implement a non-invasive remedial treatment following validation of the studied treatment approach. Furthermore, the intervention has applicability across a broad range of issues other than PTSD, such as sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, etc.

Numerous challenges have ensued about the efficacy of psychological treatments for PTSD. Clarity about the underlying mechanisms of action of the varied procedures, including ‘Gold Standard’ interventions, remains weak [6]. A classic meta-analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association rigorously explored studies of traumatized veterans treated with Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), versus non-exposure control interventions, such as meditation or waiting list controls. In the analysis, an average of 60% of PE and CPT patients ‘outperformed’ waiting list and treatment-as-usual controls demonstrating a 10 to 12-point average score decrease on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) interview [7].

The ‘clinical significance’ of the above finding, however, is debatable when one considers that sixty-six percent of the participating veterans continued to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD following the interventions. PE and CPT were deemed ‘marginally’ superior to non-exposure-based trauma interventions (e.g., mindfulness/meditation). Steenkamp et al. [7] make mention of the disproportionately high dropout rates in PE and CPT, but reasons for premature termination were not explored in any depth.

Hoge [8] noted that, among veterans who begin PTSD treatment with psychotherapy or medication, a high percentage drop out, commonly 20% to 40% in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) but considerably higher in routine practice. The rate of recovery of 60% to 80% among treatment completers declines to around 40% when non-completers are accounted for. Surveys of perceived barriers to veterans seeking treatment for PTSD include the weeks to months required to access care, possible medication side effects, and associated comorbidities [9]. There remains an intense need for rapid, remedial, and transformative approaches to successfully transition our veterans with PTSD back into the mainstream of civilian life. It is proposed that the psychologist can play a key role in bringing transformative therapies into the mainstream of practice, not only for the veteran but for the broader community.

STELLATE GANGLION BLOCK (SGB)

Suddenly, bursting out on an 11/06/19 Sunday evening [10], an amazing story about remedial hope for veterans suffering from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder was noted. The featured segment focused on an outpatient medical procedure referred to as a Stellate Ganglion Block. This procedure involves the delivery of an analgesic injection under fluoroscopy to a special bundle of neurons positioned to the right of the spine. The precise location is between cervical C6 and vertebrae C7 called the Right Stellate Ganglion. Interestingly only about 80% of humans possess this special bundle.

As professed by former combat veterans in the 60 min segment that have not responded to a myriad of medications as well as varied forms of psychotherapy for PTSD, dramatic changes ensued following the SGB procedure. These included comments such as, “felt a huge difference-can actually relax, changed mood, had control of my feelings, lifted the fog never had this relief before, game changer” [10].

RECONSOLIDATION ENHANCEMENT BY STIMULATION OF EMOTIONAL TRIGGERS (RESET THERAPY)

Paradoxically, comments of this type are also reported in another little-known experimental procedure called RESET therapy such as, “it was instantaneous; I have never slept so well in my life. It sounds too good to be true, I know. Believe me, when I first heard about it, you have no idea how skeptical I was…I was asked to compare the intensity from when we first started to how I was at the end of it and honestly, I said that it went from a 10 to a 1…I still do not really understand how this happened, but with one treatment, my wife says I am a changed man. I asked her what she meant and she said, when you came home you have become that boy, I fell in love with 25 years ago. I can feel the change in me now. I laugh again. I enjoy life and I love my wife. Since my treatment, I had been able to sleep 8 hrs. a night like I used to with no flashbacks, no nightmares and no survivor’s remorse. Also, since my treatment, I have lost 20 pounds, have more energy and I have come to enjoy life.”

Another participant noted that, “although I am a practitioner of EMDR, and neurofeedback as well, these methods were unsuccessful in making headway with this particular disturbing memory. When doctor tuned into the resonant frequency, it was like an accelerator being pushed down on a motorcycle zooming out from 0-60 mph in 1 s. The target lit up like a ball of fire, and my sympathetic nervous system engaged (huffing and puffing for breath, heart racing, sweating, cringing/squirming, tensing and bracing my muscles). While this was happening, a curious visualization came to my mind involving a mending of my trauma. My breathing slowed and in what seemed like only moments later, doctor stopped the sound.

As evident in the above two testimonials, vastly differing, non-invasive, non-verbal transformative treatment was utilized, which seemingly has similar after-effects to the invasive Stellate Ganglion Block procedure. The RESET Therapy procedure uses a non-invasive special binaural sound to temporarily unlock a part of the brain (hippocampus) where trauma memories are stored. The transformative treatment is based on the postulation that PTSD symptomology is sustained because of the memory factor, not necessarily the trauma experience itself.

Consequently, the intent in this article is to compare the two procedures (RESET therapy vs. Stellate Ganglion Block) about efficacy, as well as similarities and differences in purported mechanisms of action. It is perceived that this effort is related to the overall objective of identifying a rapid remedial intervention that can begin to alter the ‘epidemic’ referred to in the above noted 60 Minute segment. Furthermore, for those colleagues who treat family issues, the authors have found that those close to the PTSD-afflicted individual may be exposed to the effects of ‘secondary traumatization.’ Thus, the residuals of trauma may impact the family system in the form of a contagious disease that negatively impacts spousal relationships, parenthood involvement, and aggressive expression within the household [11].

RESET THERAPY

The core principles of RESET therapy are based upon three pillars of emerging neuro-scientific knowledge. The first column began with the work of Nader, et al., [12] who noted that “New memories are initially labile and sensitive to disruption before being consolidated into stable long-term memories.” In other words, each time a fear memory is reactivated, it is restored anew (reconsolidated) principally in the amygdala and hippocampus regions of the brain. Theoretically, it is perceived that these parts are equivalent to a locked storage vault for long-term traumatic memories. Following this profound discovery, the quest has been to find an efficient therapeutic key to open the vault in order to selectively modify a trauma memory in a way that neutralizes it. Ongoing efforts to weaken or alter retrieved trauma memories in PTSD continue at present [13].

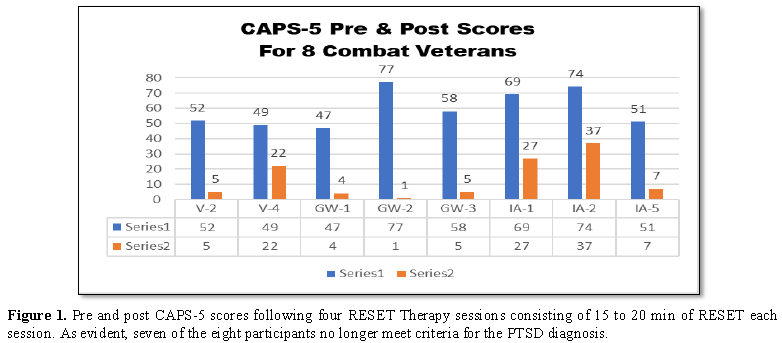

The second support column is based on psychologist Dr. Frank Lawlis’ [14] development of binaural beats later understood through research efforts to be an effective ‘key’ to unlock the hippocampal-based trauma storage vault [14,15]. Using the Bio acoustical Utilization Device developed by Lawlis [14] as part of a protocol called RESET Therapy (Reconsolidation Enhancement through Stimulation of Emotional Triggers) [15], was able to alter the CAPS-5 scores in eight combat veterans dramatically. The veteran volunteers in their study had previously served in Vietnam, Desert Storm, and the Iraq/Afghanistan conflicts. After receiving four treatment sessions of RESET Therapy, wherein the average administration time of binaural sound was for a 15 to 20 min period, the most dramatic resultant changes were noted in the CAPS-5 data (Figure 1).

Lindenfeld et al. [15] reported that as a group, participants evidenced sharp reductions in CAPS-5 total score, with group score at pre-treatment averaging 61.3 (SD=13.5), reducing to a mean score of 15.5 post-treatment (SD 14.3). The difference represents an average reduction of 55.8 points on an 80-point scale. Sample median scores agreed well with the mean scores. All but one of the veterans in the group no longer qualified for the diagnosis of PTSD, according to the CAPS-5 criteria. The level of t-test significance for CAPS-5 pretreatment to post treatment score reductions for the sample veterans was: p=0.00025. Lindenfeld et al. [15] found large CAPS-5 score reductions with RESET therapy contrasts with the earlier referenced [7] average drop of 10 to 12 points on the CAPS in their meta-analytic study of ‘gold standard’ treatments.

RESET therapy is based on the premise that trauma-induced circuitry in the brain is aberrant (trauma has its own special fixed frequency, different from one’s normal (pre-trauma) operative emotional frequency range. This aberrant frequency can be identified operationally by carefully tuning the base frequency component of a binaural sound that resonates with the selected trauma frequency (resonant frequency). The veteran is carefully instructed to ‘tune in’ to the trauma experience purely on a sensory basis. No talk (i.e., no disclosure of traumatic theme or content) is involved in the actual process.

Once the resonant (trauma) frequency is identified (delivered via a pulsed tone to the right ear via headphones), the optimal frequency level in the left ear is determined. The patient is asked to identify the moment when a calming or fading (of the experienced bodily sensations) occurs, as the therapist slowly adjusts a disruptor dial in the left ear comprised of both the resonant frequency plus an (added) offset frequency ranging from 0 to 20 Hz.

The difference between the resonant frequency (right ear) and disrupter frequency plus offset (left ear) creates a binaural beat key. The unique sound creates in the patient a subjective awareness of a third tone heard only by the patient’s brain, comprising the absolute difference in frequency (Hz) between the frequencies being delivered to the left and right ears. This binaural beat, ideally in the theta range (difference of 4 to 8 Hz between ears) effectively unlocks the emotional component of the trauma memory from the declarative component of the long-term trauma memory and rapidly re-associates the trauma memory with calming (reduced arousal) rather than fear or horror (high arousal).

Lindenfeld et al. [15] report to have observed this remedial process (fear de-conditioning vs. reconsolidation-interference) to be accomplished in as little as 5 min, evidenced by a significant distress (e.g. SUDS rating) reduction and patient report that the memory is no longer as disturbing as before. They follow up an initial 5-minute exposure trial with one-to-three additional exposure sessions, each lasting 15-20 min (involving pairing of binaural beat via headphones with the patient focusing upon sensory/somatic aspects of the trauma) [16].

The third and final column is based on a perspective that PTSD is a systemic disturbance that creates a neuroinflammatory state which induces comorbid conditions. Current studies implicate conditions of this type such as, “obesity, smoking disorders, diabetes, and in particular cardiovascular disease (CVD)” [3]. A general expectation is that “comorbidity is the rule and not the exception among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder [17]. As discussed earlier, this appears to be fertile grounds for the practicing psychologist to offer much-needed services to those who are afflicted through the impact of chronic stress, which manifests in varied ways.

A link between sleep disturbance, respiratory illness, and PTSD has been noted in a recent article [17]. The comorbid level of chronic PTSD and addictive disorders is estimated to range from 26% to 60% [18]. It is proposed that many patients utilize substance to self-medicate from the trauma effects. The presence of both conditions is associated with worse clinical consequences than either disorder alone [19].

Approximately half of the individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also suffer from major depressive disorder (MDD) [20]. Among Israeli veterans 4-6 years following exposure to war trauma, the major depressive disorder diagnosis was found to be the most prevalent PTSD comorbid condition (95% lifetime, 50% current) [21]. Finally, the triadic co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic pain and traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been associated with adverse outcomes.

Multiple regression analyses demonstrated that: (1) race, chronic pain with PTSD, alcohol abuse and MDD significantly predicted suicidal ideation; (2) pain interference, chronic pain with TBI, chronic pain with PTSD, chronic pain with TBI+PTSD, drug abuse and MDD significantly predicted violent impulses; and (3) pain interference was a more critical predictor of suicidal and violent ideation than pain intensity [22]. The psychologist may also contribute to pain diminishment both by altering earlier-referenced neuronal circuitry involved in sustaining trauma effects and by targeting the involved pain circuitry in its own right.

RECONSOLIDATION ENHANCEMENT BY STIMULATION OF EMOTIONAL TRIGGERS FORMAL STUDIES

The first published journal article regarding RESET therapy article by Lindenfeld et al. [15] appeared in the New Mind Journal in 2019, describing pilot study findings in eight combat veterans (two female participants) representing three eras, including Vietnam, Desert Storm and Iraq/Afghanistan [15]. The potential participants were required to undergo a diagnostic interview, provide a copy of their DD-214, as well as providing photocopies of medical records involving past PTSD diagnosis or treatment. The authors mention the later inclusion of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) questionnaire [23] to differentiate simple-PTSD from complex (C-PTSD). It was noted that persons with complex PTSD tend to require a greater number of sessions than those with simple PTSD.

Lindenfeld et al. [15] described their dependent measures as follows. Following acceptance into the study, each volunteer underwent a state-of-the-art bio psychosocial assessment with an independent psychometrician who was blinded to the nature and purpose of the study. The measures administered included the CAPS-5, as well as other psychological and neuropsychological measures. Participants each underwent a pre-treatment qEEG (quantitative EEG) in which they were fitted with an electrocap and assessed in an eyes-closed default condition and a trigger (activate the target) condition. EEG signal was acquired via a 19 channel J&J Engineering (Poulsbo, WA) I-330 C2+ amplifier, with modifications from the Mind-Brain Training Institute, running Physiolab USE3 software.

EEG recording of the default condition (resting state) involved maintaining stillness with eyes closed for 5 to 10 min. The second recording, referred to as the ‘activation’ or ‘trigger state,’ directed the veteran to focus his/her conscious awareness and attention upon bodily sensations and subjective experiences associated with the traumatic event. Though not necessarily intended for clinical practice, pretreatment and post treatment qEEG measurement were acquired in the ‘activate the target’ condition to provide an analog of a condition utilized during RESET therapy itself.

During the treatment phase, the veteran met with the Principal Investigator, a licensed Ph.D. Clinical Psychologist and Diplomate, for an average of four treatment sessions. Initially, the theoretic model underlying RESET Therapy was briefly explained. The researchers asked veterans to reserve judgment and assume a stance of skepticism about the procedure until they were convinced for themselves that something had changed that was beneficial in altering the quality of their lives.

The procedure was provided for five minutes in the initial exposure trial. A Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale (SUDS) was administered, based on a 0 to 10-point subjective scale rating, with 0 being neutral or no emotional distress and 10 representing the highest level of emotional distress or disturbance experienced. The objective of this step was to determine if the frequency of the selected binaural sound resonated with the predicted trauma-circuitry in the brain and if this resulted in an alteration in the experienced PTSD symptomology.

Seven of the eight veterans required four treatment sessions, with one attaining full remission of symptoms following three treatments. Within one month of the last session, the veterans were rescheduled for their psychometric evaluation as well as their post-treatment qEEG. The recorded qEEG material was inspected for artifacts and then uploaded into the New Mind Expert QEEG system database. The New Mind database was selected by the investigators because its population norms derived from a large sample of normal persons as well as subsamples of individuals with clinical histories of various conditions. Also, a discriminant function analysis derived via Neuroguide software [24] provided a second level of normative comparison (with a database more sensitive to traumatic brain injury). The discriminant function analyses suggested that it was highly probable, statistically, that half of the sample (4 of the 8 participants) had also sustained a comorbid mild to moderate Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).

About the diagnostic status of the participants, Lindenfeld et al. [15] report in their pilot study that all eight veterans met DSM-V diagnostic criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder on the CAPS-V interview at pretreatment; however, post-treatment, seven of the eight no longer met DSM-V diagnostic criteria for PTSD. One combat veteran marginally met PTSD criteria at post-treatment, yet reported substantial symptom reduction. What was especially remarkable about the findings was that all 4 of the individuals with a probable comorbid mild to moderate Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) pretreatment indicator experienced substantial reductions in PTSD symptoms.

Lindenfeld et al. [15] reported that the dramatic CAPS-5 score reductions were accompanied by less dramatic, yet objectively-determined, improvement at a brain activation level. 75% of the veterans showed a movement toward ‘normalization’ of the qEEG, suggesting a rebalancing towards a healthier, more stable and balanced, cortical activation status. The primary limitations of the study were (1) its small sample size; and (2) lack of inclusion of a sham-treatment (equivalent non-therapeutic form of auditory-stimulation), control condition and random assignment to treatment conditions.

Positive aspects of the study included: (1) the psychometrician being blinded to study purpose and QEEG psychologist diplomat being blinded to results of pre-treatment data, to minimize confirmatory bias. For example, psychometrician who administered the CAPS-V interview reportedly had been hired independently to do assessments and was unaware of key aspects of the study. Likewise, the qEEG diplomat who acquired the pretreatment and post-treatment brain map (raw) data reportedly was not able to discern (because raw data signal was involved) subtle quantitative variations in the EEG raw data as it was being recorded across sessions. Relatedly, the EEG raw data were handled by a third knowledgeable clinician who artifact the data files and then uploaded them into the New Mind Expert qEEG database to generate topographic reports, and to compare pre and post maps for a percentage of normalization of the maps following treatment.

The authors concluded that refinements in methodology were needed in future studies, including larger sample size, the inclusion of a sham-treatment control condition, random assignment to treatment condition, the inclusion of non-symptom behavioral/attitudinal measures of change, and inclusion of collateral rating measures (psychometrically-validated ratings by a knowledgeable observer). Their preliminary findings were provocative, demonstrating the potential therapeutic power (and cost-effectiveness) of this transformative innovation.

A case study of a veteran with PTSD who had been court-ordered to treatment (related to a domestic battery charge) was recently reported by Lindenfeld et al. [15] in the neurofeedback journal, NeuroRegulation, published by the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. The authors’ portent that PTSD is a systemic neuro-inflammatory state that disinhibits impulse control, including verbal as well as physical outbursts of anger and rage in afflicted individuals. The consequent cortical neuronal network in PTSD is conceptualized as having shifted from a ‘top-down’ to a ‘bottom-up’ state, prioritizing survival mechanisms over higher levels of complex functioning.

In their aforementioned preliminary studies using RESET therapy, Lindenfeld and colleagues characterize the unique features that make it attractive to the mental health clinician including:

· Its rapidity in remediating trauma symptoms

· Its minimal invasiveness from the perspective of the patient

· The use of non-verbal, exposure-based methodology, which averts a fundamental problem inherent in exposure-based therapies

· Avoidance of cumulative (secondary) exposure to the psychologically-toxic effects of trauma

From this perspective, PTSD is viewed as analogous to a contagious disease, initiated in the afflicted individual by a persistent sympathetic (fight, flight, or freeze) autonomic nervous system response. A cogent case is made that there is no singular qEEG ‘signature’ for PTSD, given that the neuroinflammatory process is variable within and across individuals. They advise consideration of the instigating vs. mitigating contributory factors and circumstances over time. One could argue the same state-of-affairs holds about current explanatory models of the underlying bio psychosocial ‘mechanisms of action’ of the PTSD condition.

It would appear that psychopharmacology has reached its limit in trying to address trauma-induced issues through psychotropic medication management. The same conclusion is evident for traditional talk-based therapies. Researchers have noted that psychological trauma involves dysfunctionality of areas of the brain that cannot be accessed or remediated through verbal means alone. No amount of talk therapy can access or remediate the speechless horror or terror often relived in the form of flashbacks and nightmares. At least three brain networks have been implicated in PTSD, including the Default Mode Network (DMN), Salience Network and Central Executive Control (CEC) Network, with their mutual activation or inhibition patterns being made dysfunctional by the disorder. Advances in the treatment of psychological trauma have been made in transformative interventions which beneficially alter the memory reconsolidation process.

These transformative therapies, which require a willingness to ‘think outside of the box’ on the part of the clinician, are based on neuroscientific breakthroughs previously unavailable. The paradigm shift is from a largely cognitive and behavioral foundation to that of a bio psychosocial and neuronal network focus. Lindenfeld et al. [15] note that the RESET therapy method spares the practitioner from exposure to raw limbic system material emoted by the patient. Despite the therapist’s efforts to limit its impact, it may affect the practitioner at subconscious levels.

The cumulative development of secondary trauma-related symptoms and other subtle negative perceptual/attitudinal shifts have been found to influence the emotional and physical well-being of the therapist. The long-term effect of shielding from this emotionally toxic contact permits the empathic psychologist to maintain his/her well-being, optimistic outlook, effectiveness and efficiency throughout a full career. Additionally, the resetting of aberrant neuronal networks has the capability of truly re-establishing neurobiological homeostasis in the afflicted patient.

The case study involving RESET therapy [1] merits further description. The authors detail the treatment of a court-involved combat veteran who was charged with Intimate Partner Violence. While in the military, he was involved in eighty-four months of combat engagement over his 32 years of active service. His vivid report of traumatic experiences while in service was provided to clarify the extent of the trauma he incurred. Within the context of RESET therapy, the traumatic material is typically not discussed, as the intervention is non-verbally based (reducing avoidance and shame in actively and privately confronting the memories on the part of the patient). Included were pre-treatment and post-treatment measures indicating dramatic positive changes, such as statistically and clinically significant CAPS-5 score reductions. The participant’s CAPS-5 score of 58 was indicative of the presence of PTSD. This elevated score was later reduced to 5 following three RESET therapy treatment sessions, which is largely unheard of in trauma treatment.

On the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationship scale (PAIR), results revealed a shift from an isolative and underlying state of anger and intimacy-avoidance to one of sociability, engagement, and increased capacity to engage in reciprocal intimacy. Given that batterer intervention programs commonly use psych educational weekly group intervention that spans 6 months or longer, yet have been criticized empirically as lacking more than modest effectiveness, perhaps consideration of concurrent or alternative cost-effective and efficient interventions is warranted.

It is at this point that a shift in focus is appropriate to the medical intervention of Stellate Ganglion Block, which has been gaining increased media attention and interest. As with the prior review of RESET therapy, startling similarities are noted in immediate results that are obtained through both interventions. SGB’s transformative changes in active duty personnel with PTSD are likewise fertile grounds for hypothesizing the existence of neuronal network(s) that contributes to sustaining PTSD symptomology. While the SGB practitioner maintains that the treatment is not permanent, permanent symptom remediation is reportedly possible through the RESET intervention. The intensive ongoing SGB research may provide us with further support that will enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanism of action of both interventions.

STELLATE GANGLION BLOCK

The Stellate Ganglion Block (SGB) is a brief outpatient medical procedure, performed by highly skilled anesthesiologists or interventional pain-management physicians. The intervention has been used to treat various disorders, including complex regional pain syndrome, hot flashes, migraines, facial pain, and upper extremity pain. The stellate ganglion is part of the sympathetic nervous system, which is found in a cluster of nerve cell bodies located between the C6 and C7 vertebrae. Injection of a local anesthetic to the stellate ganglion is thought to inhibit sympathetic nerve impulses to the head, neck and upper extremities.

The specific mechanism of action by which SGB may mitigate PTSD symptoms remains incompletely understood. A proposed explanation for the prolonged effectiveness of SGB on PTSD has been rendered. It is now believed that the targeted application of a local anesthetic to the stellate ganglion leads to an immediate and dramatic reduction in the level of sympathetic nerve activation/innervation. A resulting decrease in sympathetic (nerve) dendritic sprouting and brain norepinephrine levels is postulated to result from this intervention [25].

Ropivacaine or bupivacaine, 7 ccs of 0.5% solution, are the most common anesthetic types and dosages used in SGB. The use of image-guidance techniques is advised to avoid potentially serious adverse effects of inaccurate needle placement to the anatomy surrounding the stellate ganglion. Procedures such as ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or computed tomography are recommended to help visualize the injection area. SGB performance also requires the availability of continuous vital sign-monitoring technology and resuscitative equipment and personnel, to monitor and respond to changes in respiration and circulation that may occur as a result of unintentional intravascular injections [26].

The stellate ganglion is involved in the sympathetic ‘fight and flight’ neural/adrenal response network and, tends to be chronically hyper activated in conditions such as PTSD. As chronicled by CBS 60 Minutes, within minutes of the first injection by an anesthesiologist or interventional pain management physician, two military veterans described an experience of being liberated from the chronic hyper arousal of PTSD and sensing a normal level of arousal for the first time since their pre-military service.

RECENT STELLATE GANGLION BLOCK STUDIES FOR PTSD

A series of case studies referenced by Hanling et al. [27] was utilized to treat 27 PTSD involved veterans, with the results found to be very promising. Consequently, the procedure received widespread attention following the publication of a case series of 166 Special Forces active military veterans who elected to receive the procedure at Walter Reed Medical Center. These participants were assessed with a PTSD checklist (PCL) the day before the procedure, one week following and at three months and six months post-procedure. The authors reported a success rate of 70%, defined as a sustained reduction of 10 or more points on the PCL [28].

However, when the procedure was subjected to tighter experimental control, the outcome was quite different. A study conducted at San Diego Naval Hospital randomly assigned 41 military veterans with PTSD to an active treatment condition (SGB) versus a sham treatment condition (placebo injection of saline). The participants and the assessors were blinded to the purpose of the study. The researchers reportedly replicated the procedures described in the preceding Mulvaney et al.’s study [28] concerning the injection site and dosage of the analgesics provided.

Participants in the sham treatment group were allowed to cross over to the treatment group, and participants who met criteria for PTSD were allowed to receive a second SBG treatment. While symptoms (PTSD, depression, anxiety) improved across time in both groups, there were no statistically significant differences between the active and control conditions, thereby failing to replicate the findings of the earlier studies [29].

Calling for caution and continued research [27] cited an example of a 53 year old veteran with a 10+ year history of PTSD who upon receiving his first injection (placebo), reported a sense of wellness and a lifting of anxiety to where he felt the best he had in over a decade. After the second injection (SBG), the veteran noted, “similar but less dramatic results.” Feeling well enough to take a trip with his family for several weeks, he suffered a significant relapse of symptoms over the course of a day, but indicated that he would be willing to undergo the procedure again multiple times if he could attain the same level of improvement he had experienced with the first two injections [27].

Lipov [30], an anesthesiologist/researcher, involved in many of the earlier studies, critiqued differences between the Mulvaney et al. [26] and Hanling et al’s [27] outcomes, based primarily on methodological grounds [29]. The experimental group was roughly twice the size of the control group, hence a lack of equivalent group sizes. Lipov [30] contends that procedures used in the RCT differed from those of earlier studies regarding the exact site of injection, noting that a much lower dose of the active analgesic medication was used in the Hanling et al. study [29].

There were qualitative differences, as well, between the populations of military veterans under study. In the Walter Reed study, the participants were active duty Special Forces, whose group norm was to deny PTSD symptoms. However, upon learning of the magical results experienced by others, some of these individuals may have initially over reported symptoms to qualify for eligibility for the study and, then minimized symptoms following the study to be deemed fit to return to duty ASAP.

Alternatively, in the San Diego Naval Hospital Study, many participants were characterized as ‘part-timers’ who were close to discharge, and who were applying for service-connected benefits for PTSD, and hence may have had a vested interest in maintaining higher levels of symptoms before and after treatment. Neither study provided sufficient focus upon treatment dropouts or non-responders, nor was potential side effects given sufficient emphasis [25,27,30].

Reviewing the research from the perspective of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Peterson et al. [25] found that SGB might have an inhibitory effect upon neural connections between the peripheral sympathetic nervous system and the central sympathetic nervous system, thought to be persistently hyper activated in PTSD. Potential benefits of SGB include the elimination of negative stigma associated with seeking treatment by labeling it as a biological intervention to manage symptoms. Other claims are that it offers rapid near-immediate symptom relief and improved compliance because it does not require daily or weekly administration.

The above researchers suggest that until a more conclusive investigation has been conducted demonstrating safety and efficacy, there is not sufficient evidence for widespread clinical use of the procedure. Nevertheless, the intervention may be viewed as an initial treatment or bridge that allows sufficient reduction of hyper arousal to permit involvement in other evidence-based interventions. Whether or not VA will opt to invest in experimental research on the utility of PTSD, versus other promising interventions (e.g. stimulation-based) remains an open question at this point. U.S. Army Medical Research is currently funding a three-year, $2 million single-blinded placebo control study of SGB involving 242 active duty personnel diagnosed with PTSD. The study began late in 2015 and formal publications of the results are expected by summer or late 2019.

FUNCTIONAL NEUROANATOMY

In this section, similarities between RESET therapy and SGB are compared to seek a commonality between the two approaches that independently appear to produce a significant diminishment of hyper arousal in the PTSD-afflicted individual. Supportive evidence concerning neuroanatomical links between auditory stimulation and limbic-system-mediated emotional responding is present from several lines of investigation [31]. A review of the effects of music and its impact on the neurochemical systems related to stress and arousal; the immune system, reward, motivation and pleasure as well as social affiliation was provided by Chanda and Levitin [32].

The auditory steady-state evoked potential (SSEP) in the scalp electroencephalogram (EEG) is “an evoked neural potential that follows the [frequency] envelope of a complex stimulus. It is evoked by the periodic modulation or turning on and off, of a tone [clicking]” [33]. Reports of the functional neuroanatomy underlying the auditory SSEP supported the contention by Lindenfeld et al. [34] that “through the acoustical pathway we can directly modulate neural activity in the amygdalohippocampal circuit during memory retrieval and reconsolidation.”

Investigations of auditory fear conditioning have shown that auditory stimulation, fear, the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus and the basolateral complex of the amygdala are intertwined [35-37]. These kinds of interactions are most likely the behavioral and neuro-anatomical basis for the clinically-observed success of RESET therapy as well as the stellate ganglion block. Alternative investigations of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in humans have revealed that it is capable of changing emotional behaviors. This effect may be analogous to auditory stimulation [38,39].

Sufficient evidence exists supporting the presence of neuroanatomical links between auditory stimulation and emotional responding. Additionally, evidence implicates the amygdala in memory reconsolidation and fear conditioning. Now, consider this statement concerning SGB.

Better understanding of sympathetic neuroanatomy via anatomical labeling techniques is starting to support explanations of the extensive effects of SGB for treatment of hot flashes, PTSD and neuropathic pain. In the course of mapping the sympathetic nervous system to the related regions of the cerebral cortex, Wampold [6] used pseudo rabies virus injections to identify connections of the stellate ganglion. Pseudorabies virus allows identification of neural pathway connections that are 2-3 synapses from the point of injection of the virus. Early labeling was found in the hypothalamus and central nucleus of the amygdala. With slightly longer time, labeling was found in the lateral, basolateral and medial amygdalae. After 6-8 days, injections of the stellate ganglion produced extensive trans-neuronal labeling in the infralimbic, insular and ventromedial temporal cortical regions [40].

Using additional information from other sources, Lipov et al. [40] proposed the following, evidence-based hypothesis: We believe that CRPS (chronic regional pain syndrome), hot flashes and PTSD are centrally-mediated, where a relevant insult leads to increase in NGF levels, which starts a cascade that leads to sympathetic sprouting, which further increases brain norepinephrine, which finally leads to the clinical conditions described in this article. Reversal of this cascade occurs by application of the local anesthetic to the stellate ganglion, which reduces NGF, which reduces sympathetic sprouting, leading to the reduction of the brain norepinephrine, which finally results in resolution of symptoms of CRPS, hot flashes and PTSD. This hypothesis provides a plausible explanation for the prolonged effect of the local anesthetic markedly beyond the length of the half-life expected by the pharmacokinetics of the local anesthetic [40].

A primary focus on the proposed feedback mediated by the 2nd and 3rd order connections from the stellate ganglion of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to the amygdala appears to be a common link to both procedures. Lanteaume et al. [41] noted that “our findings provide major evidence of a link between emotional affect, facial expressions, sympathetic activity and amygdala stimulations in humans”. Narayanan et al. [36] concluded that the reconsolidation of remote contextual fear memory includes changes in theta-frequency interactions between the lateral amygdala and hippocampal area CA1.

An additional investigation of the amygdala showed that it encodes, stores, and retrieves episodic-autobiographical memories (EAM). Markowitsch et al. [42] provided extensive evidence that the “amygdala’s main function is to charge cues so that mnemonic events of a specific emotional significance can be successfully searched within the appropriate neural networks and reactivated”.

The amygdala mediates activation of the SNS, which is involved in the reconsolidation of remote contextual fear memory. Furthermore, it supports the search for mnemonic events of a specific emotional significance within appropriate neural nets, leading to their re-activation. Applying the Lipov’s [40] hypothesis to these characteristics of the amygdala, one may conclude that positive feedback from the stellate ganglion of the SNS, via 2nd and 3rd order neurons may enhance these functions to a significant degree. Thus, SGB may act to block positive feedback, thus lessening or preventing the involuntary re-activation of unwanted, fear-associated memories that occur in PTSD. Conversely, there is a parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) neuromodulation therapy used in humans that provides some context for the idea that SGB may calm a positive feedback loop associated with PTSD symptoms through vagal nerve stimulation (VNS).

VNS uses intermittent stimulation of the left vagus nerve in the neck to reduce the frequency and intensity of [epileptic] seizures. [The] mechanism of action of VNS remains uncertain, but stimulation does not induce grossly visible alterations in the human EEG. Recent studies suggest that metabolic activation of certain thalamic, brainstem and limbic structures may be important in mediating the effect of VNS. Depletion of norepinephrine in the locus coeruleus attenuates the anti-seizure effect of VNS [43].

In theory, afferent VNS elevates norepinephrine release in the locus coeruleus (LC). The LC has widespread effects in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system (ANS). At one time, the LC was thought to be a major player in a diffuse ascending reticular activating system (ARAS). Now we understand that the LC has many specific functions in the brain [44,45]. Stimulation of the LC causes adrenergic inhibition of preganglionic parasympathetic ganglia. It also causes, among many other effects:

· Release of the excitatory neurotransmitter noradrenaline in the neocortex,

· Excitation of anxiety responses mediated by adrenergic neurons in the amygdala,

· Possible declarative memory enhancement mediated by adrenergic neurons in the hippocampus,

· Stress responses by the ANS mediated by adrenergic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

The effects of VNS are likely to enhance symptoms of PTSD, with this certainly being an untoward side-effect in patients with intractable epilepsy. However, from these observations, it may be surmised at the most basic contextual level that, if parasympathetic influences (i.e., VNS) on the amygdala may enhance PTSD symptoms, then SNS influences (i.e., SGB) may have the opposite effect (Table 1).

A brief examination of functional neuroanatomy suggests that parallel neuromodulatory mediations of auditory stimulation and SGB are available for the treatment of PTSD. Neuroanatomical links are present between auditory stimulation and limbic-system-mediated emotional responding. The amygdala has been implicated in memory reconsolidation and fear conditioning.

Evidence supports a proposed feedback connection from the stellate ganglion via 2nd and 3rd order connections to the amygdala. The effects of this sympathetic SGB connection may be compared and contrasted with parasympathetic VNS neuromodulation, which has the potential to exacerbate PTSD. Whether PTSD-related neuromodulation occurs via auditory stimulation, SGB or VNS, questions remain: At what neurobiological level(s) are the effects manifested and how long do they last?

SBG is an invasive medical procedure, intended for management of PTSD hyper arousal symptoms over time. In some ways, it is similar to a steroidal epidural procedure for chronic pain, which reduces inflammation temporarily. The consequent physical pain relief may last for weeks to months before a repeat procedure is needed. As noted earlier, any intervention targeting areas close to the spine and major arteries and veins may involve risks of adverse effects.

The SGB procedure is still considered to be experimental and has not been studied well enough to determine cumulative effects upon efficacy (e.g. improved efficacy after several injections) or whether the neural circuitry may begin to habituate to the effects over time, rendering it less effective in potency or duration. SGB does not permanently alter the characteristics (e.g. dominant or resonant frequency and amplitude) of the neuron network of PTSD, which postulates a rebalancing of sympathetic (e.g. reticular activating system, amygdala, limbic system, cingulate cortex, prefrontal cortex, hemispheric asymmetries) and parasympathetic (limbic, vagal) circuitry.

In contrast, while RESET therapy is also considered experimental, it appears to produce a reboot of the involved neuronal network, leading to the rebalance of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, as evidenced in qEEG pre and post-treatment findings. Practically speaking, this means that the long-term effects of exposure to a neuroinflammatory state alter back to a pre-trauma level. Through this transformative change, later difficulties such as delayed onset PTSD are minimized. From the psychologist’s perspective, the patient is now fully available for therapeutic involvement. Previously, the patient was operating from an emotionally and instinctively based ‘protect and defend’ mode, referred to as a ‘bottom-up.’ With a successful transformative experience, higher level abilities attain inhibitory control over subcortical emotional processes, once again.

RESET therapy is a minimally invasive procedure. Like SBG, immediate positive effects have been reported, at least episodically, after an initial 5 min exposure trial. The method involves the accurate identification and pairing of the binaural beat with the patient’s directed attentional focus upon physiological/sensory experiences/changes elicited via recall/reactivation of the traumatic memory. Lasting, permanent reductions in PTSD symptoms to subclinical levels have reportedly been demonstrated via preliminary prospective research within one to four sessions of RESET therapy, although controlled studies have not yet been conducted to include a sham control (placebo control) group and blinded research design. The permanent symptom changes facilitated by RESET therapy are associated with significant shifts toward normalization of qEEG patterns. Topographical brain mapping suggests reorganizational activity occurring at the cortical level involved in normalizing asymmetry and cortical activation patterns, which is consistent with our tenets of a neuronal model of PTSD.

SGB requires a high level of trust in the clinician administering the procedure because of the risk of infrequent but potentially very serious complications. In contrast, the RESET therapy practitioner reportedly encourages an initial stance of healthy skepticism on the part of the veteran until the patient is convinced that significant symptom relief has occurred. Furthermore, the difference in potential cost over time is dramatically different between RESET therapy and SGB. SGB costs have been estimated to be lower than conventional PTSD therapies, i.e., $2,000 for two SGB injections vs. a range of $6,000 to $30,000 for other conventional psychological and psychiatric interventions [25]. Two SGB injections may be expected to last at least six months (based on the large N studies to date) to perhaps a year. The expectation is that once the beneficial effects eventually wear off, the series of two injections will need to be repeated, perhaps on an annual basis.

RESET therapy in uncomplicated (simple) PTSD cases, requires a typical expectation of one to four outpatient treatment sessions, each costing $150, which could potentially eradicate uncomplicated PTSD. Side effects have temporary and minimal effects including lightheadedness, mild headache, mild jitteriness or post-adrenalin symptoms, fatigue. By contrast, the estimate for aversive effects with SGB, while quite low, is reported at 0.002 for risk of death or damaging physical consequences. Also, as described earlier, only 80% of humans are estimated to have the stellate ganglion available for the procedure, thus leaving one in five without the SGB intervention possibility.

It appears that initial training and certification of licensed mental health practitioners in the RESET therapy method and acquisition of the commercially available technology are significantly lower in time and costs than that required of other bio psychosocial interventions. Moreover, rather than repeat administrations of SGBs, veterans with treatment-resistant PTSD can be issued their portable treatment device (BAUD unit) with instructions about how to tune the unit to address PTSD-related issues as well as other mental health-related issues, including anxiety, depression, anger and chronic pain. In rural areas, they may also be followed via telecommunications by a skilled and properly-trained psychologist practitioner.

SGB seemingly appeals to active military personnel because it allows a quick temporary fix to allow the soldier to return to his/her unit rapidly. After military discharge, however, the role of SBG is less clear-cut. It may appeal to the younger veteran in distress who needs a quick fix (rapid re-stabilization) and who is unwilling or unable to engage in the more difficult emotional work of tackling the root causes of PTSD, as currently available.

Veterans with PTSD who have navigated the VA system have usually experienced partial measures, such as being provided with medications that may somewhat reduce arousal, but not sufficiently effective to address the central issues of intrusive material, insomnia, hyper-vigilance and avoidance. With their PTSD, at best, partially-treated, many of these veterans remain unable to function at their previous level in civilian society and begin the game of the VA benefits process, which rewards sickness rather than health. RESET Therapy could play a pivotal early intervention role when active duty veterans first enter the VA system.

Since RESET is a non-verbal treatment, patients are not required to disclose their traumatic experiences [1,15]. The sole directed focus is upon sensory awareness during brief exposure sessions, involving the presentation of individually-attuned binaural beats (co-awareness of bodily sensations and the pulsed, individually-attuned sound. By aggressively and effectively targeting PTSD early on with effective measures, such as RESET therapy, the pattern of ineffective treatment leading to pursuit and maintenance of disability can be effectively disrupted, improving lives and resulting in tremendous savings and reinvestment in new technologies to combat challenging healthcare-related issues by the Federal Government.

SUMMARY

The authors compared and contrasted two fascinating and rapidly transformative interventions for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder that initially appear to demonstrate high levels of success with minimal treatment complications, side effects or treatment dropouts. One noteworthy treatment that has been the focus of increased attention by the media is an outpatient medical procedure called Stellate Ganglion Block, delivered by skilled anesthesiologists or interventional pain management physicians.

The second transformative intervention is a little-known auditory stimulation-based, brief exposure intervention called Reconsolidation Enhancement through Stimulation of Emotional Triggers (RESET therapy) provided by psychologists and other trained mental-health professionals. Stellate ganglion blocks have been used for many decades to address varied medically-based, pain-related conditions. Similarly, auditory stimulation has been used therapeutically in numerous applications other than PTSD. It has only been the past decade that the two approaches have been applied successfully for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder.

As earlier described, SGB is a brief, precisely targeted procedure that potentially provides a dramatic reduction of sympathetic nervous system arousal within one or two treatments. It is newly-intended for emotional pain relief, as opposed to its previously targeted use for chronic pain. The intervention is labeled as not being a cure for PTSD, which is expected to recur once the therapeutic effects of the injection have worn off. There is an apparent absence of new learning or permanent neural reorganization with the SGB procedure. Rather, there is a temporary inhibition and quieting of a persistently hyper activated autonomic nervous system.

Bearing aspects of similarity to SGB, RESET therapy is brief and precisely targeted. There is no verbal disclosure by the patient of the traumatic memory. The patient is initially prepared for the procedure by the treating psychologist by being alerted that he/she will likely experience rapid and intense shifts in arousal in response to changes in auditory frequency stimulation. The ‘tuning in’ process is designed to identify the resonant trauma frequency, and the corresponding optimal offset setting, producing a binaural beat ideally in the theta range (activating the parasympathetic nervous system), which is central to the potential success or failure of the intervention. An initial five-minute exposure trial (pairing focus upon sensory experiences associated with the recall of the trauma with the continuous binaural beat delivered via headphones) provides a preliminary indication as to whether or not the derived settings successfully altered hyper arousal associated with trauma recall.

RESET therapy is hypothesized to interfere with the reconsolidation of the traumatic memory by leaving the explicit (declarative) aspect intact while altering the subjective (implicit) emotional valence aspect of the memory. It is hypothesized that the temporary success of the Stellate Ganglion Block procedure confirms a hypothesis of PTSD being a systemic disorder, rather than solely a psychologically-based condition. RESET therapy purportedly rebalances the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems by inducing changes in patterns of activation and deactivation involving aspects of the neural networks that are involved in fear of learning, including neural feedback loops.

With successful intervention, normative hemispheric asymmetries and blood flow patterns are re-established; over activation reduces in the right hemisphere and under-activation in the left hemisphere reverse. The prefrontal lobe regions normalize their activation patterns and the previously overactive right and central parietal and bilateral occipital areas become stabilized. In other words, cortical activity reboots back to normal premorbid levels of activation.

Unanswered questions remain regarding long-term use of SGB. For example, does SGB have a cumulative effect whereby a series of injections works additively to facilitate optimal results over time? Alternatively, do the neurons in the Stellate Ganglion Block begin to habituate to the procedure over time, with symptom relief becoming progressively lesser in degree and duration? Does using an artificial means of inhibiting the brain’s sympathetic nervous system over time have any deleterious effect upon the brain’s neuroplastic capacity to self-regulate and self-organize? All of these are currently unanswered questions.

The smaller number of formal studies of RESET Therapy, including both of the [1,15] studies, has shown dramatic, positive, rapid and seemingly lasting non-invasive results. However, follow-up evaluations have not occurred due to lack of funding. All studies to date were conducted on a pro-bono basis. A prevalent hope is that researchers in the future can obtain adequate funding to finance studies using improved methodologies such as a larger sample size, random assignment to either active treatment or sham treatment control. Inclusion in the latter group would need to include subsequent crossover so that those in the control group subsequently receive the benefit of RESET therapy. Finally, in any unbiased treatment study, there needs to be adequate blinding of participants and assessors/raters.

As clinicians who have worked with veterans, the authors dare to dream that someday, somewhere close to a base of a distant military operation, a trained corpsman with psychological supervision, adequately trained in RESET therapy, will immediately address a service member’s adverse reaction to a traumatic experience. To take this dream a step further, within the VA system, early intervention via a transformative treatment such as RESET or SGB can achieve rapid relief, potentially reducing the need for later costly specialty treatment, inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations or referral to specialized PTSD programs.

Furthermore, in complex PTSD cases, the veteran can be issued his or her treatment unit with RESET training provided by his/her treating psychologist. Supervised telecommunication can enhance self-applied efforts through the provision of supervision at needed transition points. Through procedures such as these, the PTSD intervention can be destigmatized and reframed as a biologic intervention designed to rebalance the nervous system rather than referring to it as an illness.

Theoretically, early implementation of a transformative treatment for PTSD could increase medical compliance, improve life satisfaction for veterans and their families, and reduce the financial burden upon the Federal Government for the perpetual care of trauma-altered veterans. In theory, this would allow an increased number of veterans to have treatment available rapidly and effectively. Given the heartbreaking failure of current evidence-based treatments to adequately treat PTSD (only about 40% of cases seeking treatment receive it and of those individuals, only about 60% get some symptom relief), we dare to dream of a future where these dismal percentages significantly alter. Our dream includes a major shift in the unacceptably high suicide rates among veterans.

When hope replaces despair, when healthy passion replaces apathy, when engagement replaces withdrawal and isolation, self-destructive ideation becomes a distant and fleeting past thought, rather than a perceived solution to unbearable and inescapable life experiences. As psychologists, we expect that our colleagues in other healthcare disciplines will quickly accept and utilize transformative therapeutic approaches such as SBG and RESET, once these approaches have been deemed to have sufficiently met the rigors of scientific inquiry through multiple research inquiries. The advent of transformative treatment as an emerging therapeutic approach is upon us. Will we, as independent psychology practitioners, rise to the impending challenges thrust upon us or will we continue to opt for the status quo?

1. Lindenfeld GL, Rozelle G, Hummer J, Sutherland MR, Miller JC (2019) Remediation of PTSD in a combat veteran: A case study. NeuroRegulation 6: 102.

2. Hori H, Kim Y (2019) Inflammation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiat Clin Neuros 73: 143-153.

3. Schenone AL, Jaber WA (2019) The neuro-hematopoietic-inflammatory arterial axis: The missing link between PTSD and cardiovascular disease? J Nucl Cardiol.

4. Krystal JH, Davis LL, Neylan TC, Raskind MA, Schnurr PP, et al. (2017) It is time to address the crisis in the pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: A consensus statement of the PTSD psychopharmacology working group. Biol Psychiatry 82: e51-e59.

5. Lipov E, Tukan A, Candido K (2018) It is time to look for new treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder: Can sympathetic system modulation be an answer? Biol Psychiatry 84: e17-e18.

6. Wampold BE (2019) A smorgasbord of PTSD treatments: What does this say about integration? JPI 29: 65-71.

7. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, Marmar CR (2015) Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA 314: 489-500.

8. Hoge CW (2011) Interventions for war-related Post-traumatic stress disorder: Meeting veterans where they are. JAMA 306: 549-551.

9. Navaie M, Keefe MS, Hickey A, Mclay RN, Ritchie E, et al. (2014) Use of stellate ganglion block for refractory post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of published cases. J Anesth Clin Res 5.

10. Whitaker B (2019) SGB: A possible breakthrough treatment for PTSD: A simple shot in the neck could put PTSD sufferers on the path to recovery. CBS News 60 minutes.

11. Horesh D, Brown AD (2018) Post-traumatic stress in the family. Front Psychol 9: 40.

12. Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE (2000) Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature 406: 722-726.

13. Kida S (2019) Reconsolidation/destabilization, extinction and forgetting of fear memory as therapeutic targets for PTSD. Psychopharmacology 236: 49-57.

14. Lawlis F (2006) About the BAUD.

15. Lindenfeld G, Rozelle G, Soutar R, Hummer J, Sutherland M (2019) Post-traumatic stress remediated: A study of eight combat veterans. New Mind Journal.

16. Knowles KA, Sripada RK, Defever M, Rauch SAM (2019) Comorbid mood and anxiety disorders and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in treatment-seeking veterans. Psychol Trauma 11: 451-458.

17. Waszczuk MA, Ruggero C, Li K, Luft BJ, Kotov R (2019) The role of modifiable health-related behaviors in the association between PTSD and respiratory illness. Behav Res Ther 115: 64-72.

18. Vujanovic AA, Back SE (2019) Post-traumatic stress and substance use disorders: A comprehensive cinical handbook. Routledge.

19. Vojvoda D, Petrakis I (2019) Trauma and addiction-How to treat co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. The Assessment and Treatment of Addiction, pp: 189-196.

20. Flory JD, Yehuda R (2015) Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: Alternative explanations and treatment considerations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 17: 141-150.

21. Bleich A, Koslowsky M, Dolev A, Lerer B (1997) Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression: An analysis of comorbidity. Br J Psychiatry 170: 479-482.

22. Blakey SM, Wagner HR, Naylor J, Brancu M, Lane I, et al. (2018) Chronic pain, TBI and PTSD in military veterans: A link to suicidal ideation and violent impulses? J Pain 19: 797-806.

23. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14: 245-258.

24. Applied Neuroscience, Inc. Most affordable EEG & QEEG Analysis and Neurofeedback software.

25. Peterson K, Bourne D, Anderson J, Mackey K, Helfand M (2017) Evidence brief: Effectiveness of stellate ganglion block for treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

26. Mulvaney SW, Lynch JH, Kotwal RS (2015) Clinical guidelines for stellate ganglion block to treat anxiety associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Spec Oper Med 15: 79-85.

27. Hanling S, Fowler IA, Hackworth RJ (2017) Stellate ganglion block for post-traumatic stress disorder: A call for clinical caution and continued research. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

28. Mulvaney SW, Lynch JH, Hickey MJ, Rahman-Rawlins T, Schroeder M, et al. (2014) Stellate ganglion block used to treat symptoms associated with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: A case series of 166 patients. Mil Med 179: 1133-1140.

29. Hanling SR, Hickey A, Lesnik I, Hackworth RJ, Stedje-Larsen E, et al. (2016) Stellate ganglion block for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 41: 494-500.

30. Lipov E (2017) To the editor: Stellate ganglion block for post-traumatic stress disorder: A call for the complete story and continued research. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.

31. Miller JC, Lindenfeld G (2017) Auditory stimulation therapy for PTSD. 88th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Aerospace Medical Association, Denver CO.

32. Chanda ML, Levitin DJ (2013) The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn Sci 17: 179-193.

33. Stach BA (2002) The auditory steady-state response: A primer. Hearing J 55: 10,14,17,18.

34. Lindenfeld G, Bruursema LR (2015) Resetting the fear switch in PTSD: A novel treatment using acoustical neuromodulation to modify memory reconsolidation.

35. Maren S, Yap SA, Goosens KA (2001) The amygdala is essential for the development of neuronal plasticity in the medial geniculate nucleus during auditory fear conditioning in rats. J Neurosci 21: RC135.

36. Narayanan R, Seidenbecher T, Sangha S, Stork O, Pape HC (2007) Theta resynchronization during reconsolidation of remote contextual fear memory. Neuroreport 18: 1107-1111.

37. Paré D (2003) Role of the basolateral amygdala in memory consolidation. Prog Neurobiol 70: 409-420.

38. Krack P, Hariz MI, Baunez C, Guridi J, Obeso JA (2010) Deep brain stimulation: From neurology to psychiatry? Trends Neurosci 33: 474-484.

39. Dunn JD, Orr SE (1984) Differential plasma corticosterone responses to hippocampal stimulation. Exp Brain Res 54: 1-6.

40. Lipov EG, Joshi JR, Sanders S, Slavin KV (2009) A unifying theory linking the prolonged efficacy of the stellate ganglion block for the treatment of chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS), hot flashes and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Med Hypotheses 72: 657-661.

41. Lanteaume L, Khalfa S, Régis J, Marquis P, Chauvel P, et al. (2007) Emotion induction after direct intracerebral stimulations of human amygdala. Cereb Cortex 17: 1307-1313.

42. Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A (2011) Amygdala in action: Relaying biological and social significance to autobiographical memory. Neuropsychologia 49: 718-733.

43. Fisher RS, Handforth A (1999) Reassessment: Vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy: A report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 53: 666-669.

44. Samuels ER, Szabadi E (2008) Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: Its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part I: Principles of functional organisation. Curr Neuropharmacol 6: 235-253.

45. Weinberger NM (2011) The medial geniculate, not the amygdala, as the root of auditory fear conditioning. Hear Res 274: 61-74.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- International Journal of Internal Medicine and Geriatrics (ISSN: 2689-7687)

- Journal of Neurosurgery Imaging and Techniques (ISSN:2473-1943)

- BioMed Research Journal (ISSN:2578-8892)

- Journal of Carcinogenesis and Mutagenesis Research (ISSN: 2643-0541)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- International Journal of Radiography Imaging & Radiation Therapy (ISSN:2642-0392)