239

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

The definition of street food as given by Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO 1986 / 1987) stipulate that it is the type of food and beverages prepared by vendors or hawkers in advance ready-to-eat at the kiosk or as a take away for consumption. It also includes raw foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables (Lamuka, 2014). Other street food definition is given by Thomas, Holbro and Young, 2013 that; Street foods are a wide range of ready-to-eat foods and beverages which have been prepared in advance and brought in the streets for sale and consumption. The world food organization (WHO) define street food as the type of food and beverages which has been produced and sold to customers by vendors or hawkers without further processing (Al MM, Rahman & Turin, 2013).

In many countries’ street foods is seen as a type of business with many advantages but the major ones are; employment for many people who are job less considering the unemployment status of many countries. Second, is catering provider offering local and traditional dishes which are nutritious at a low competitive price for the populations.

Street food is very popular now and in the next decades it will become even more popular and important as the population and settlements of people migration from countryside and villages to urban cities is rapidly increasing and will require these services (Battersby and Watson, 2018). However, Naibbi Ali & Healey, 2013 pointed out the negative aspect of street food business in urban that affect the environmental degradation in the countryside where there is an over harvest of firewood and charcoal for the street food cooking.

On the other hand, the health authorities should be kept alert because apart from many benefits, street foods are perceived as dangerous for the population health. In many developing countries the street food vendors profile includes poor education background, lack proper training and poor knowledge on personal hygiene, cleanliness, sanitation safe food handling and storage. Also, street food vendors do not comply personal hygiene rules and catering rules before and after food handling.

It has been discussed by many researchers that in several developing countries street food business has been carried out for the past many years without official recognition. Due to unemployment and poverty this business has been received as a savior and good omen offering employment opportunities and business for the youth and women who does not have large capital and experience to establish large business (FAO, 2013, Winarno & Alain, 1991, Addo-Tham,2020, King, 2000).

Normally, street foods are prepared and sold in the busy streets of cities or towns where there are large crowds of people i.e. bus and train stations, stadiums, schools, hospitals, churches, mosques, industrial areas and at construction buildings. Sometimes It is brought to the door step of the customers, but usually food is brought and sold on trucks, food stalls, food van, mobile on carts (Guta) or (Mkokoteni). Some vendors carry cooked food on baskets, trays and distributing to offices or homes and kiosks and served on tables laid down on open air or sometimes on shelters.

However, street food business is also a major source of income and revenues for the local food vendors and the respected country government levies and taxes (Cortese, 2016, Anandhi, Janani, Krishnaveni, 2015; Muzaffar, Huq & Mallik, 2009).

The food agriculture organization gave an approximate figure of 2.5 billion people eating street food every day (Monney, 2014). The food sold is inexpensive, reasonable price and affordable meeting all the food tastes and nutritious requirements for majority of different category of customers (Monney, 2014). The street foods business has proved to be very lucrative with great support to millions of low-income people livelihood and generating enormous contribution to the country economy (Lihua Ma, Hong Chen, Huizhe Yan, Lifeng Wu & Wenbin Zhang, 2019; Aimm, Rahman, & Turin, 2013; Roever, 2010; Battersby & Crush, 2014).

Virtually, apart from the countless benefits of street food to the country and residents the risk and chances for outbreaks of cholera and other food borne diseases is very high for the population. Concerted efforts are required to curb the outbreak and diseases as street foods are sold and consumed to different groups of people the old, the poor, adults, youth and children of different ages.

In Tanzania, the street food business is faced with many challenges which almost are the same as to other developing countries. From dirty preparation surroundings, poor supervision and control by health authorities and lack of training in food and personal hygiene for street food vendors. Others include; very weak or non-existence of food hygiene rules and regulations and enforcement, poor utility, waste and garbage disposal facilities, and poor temperature-controlled food storage facilities (Khomotso, 2020; Thomas, Holbro &Young, 2013).

LITERATURE REVIEW

In many countries of the world, street foods vending is very popular and attracts people of all age groups from different backgrounds and its contribution to the livelihood of many low-income people and the poor is recognized and appreciated by many governments.

The street food vendors are also known as entrepreneurs are self-engaged and motivated working under informal sector of the country economy. Their activities are not supervised nor monitored by any institution and their success solely depend upon individual strengths and performance (mtaji wa masikini ni nguvu zake mwenyewe) (Thomas, Holbro &Young, 2013; Hossen, Ferdaus, Hasan, Lina, Das, Barman, Paul & Roy, 2021).

The street foods business is challenging and attracts the entrepreneurs who find it beneficial generating significant income taking care vendors, families and dependents (Brown, Lyons & Dankoco, 2010).

The street foods play an important socioeconomic role in meeting food and nutritional requirements of consumers and are appreciated by its customers for convenience, taste and reasonable prices (Muinde & Kuria, 2005). Consequently, street food vendors are appreciated by many people because they are seen as uneducated and do not care to adhere to personal hygiene and general cleanliness rules as a result all the street foods benefits are washed away by these allegations. Concerted efforts are required to change this negative image for the street food vendors (Al MM, Rahman, Turin, 2013).

In developing countries, street foods have become very important provider of catering services to the low-income people, the poor and other categories of people consuming this type of food. However, street foods also pose a serious threat to the local residents because it is prepared and served under very dirty surroundings that easily can be associated with cholera and typhoid outbreaks and other food borne diseases. Also, there is giant problem of killer disease malaria which is a water related parasitic infection and schistosomiasis. In Tanzania scientists has linked these parasitic infections to poor sanitation and hygiene happening often (Thomas; Holbro, Young, 2013).

It is important that proper controls on hygiene, sanitation and cleanliness are kept in place and regular training is carried out to the street food vendors on food safety and personal hygiene (Kharuzzaman, Chowdhury, Zaman, AlMamun and Bari, 2014).

In Tanzania, unemployment is very high due to the economic challenges which the government is facing making it difficult to engage potential workers in the labour market. Those who have not succeeded to find employment in the government and other institutions takes up informal employment and these include Moshi urban residents who upon failing to secure formal employment have engaged to informal food vending as a source of livelihood and employment as such their decision has reduced unemployment and dependency to the Moshi municipality (Brown, Lyons & Dankoco, 2010; Thomas, Holbro & Young, 2013).

The cost of street foods is usually competitive compared with that purchased in large food establishments, such as hotels, restaurants, airline catering and fast food outlets. The street food vendors purchase their food stuffs from the source market at a bargaining price and the foodstuffs are normally fresh from the farms. This has contributed for the vendors lowering their food selling prices and their foods tasting fresh and palatable.

It has been established that about 70% of disease outbreaks have been linked to street-vended foods a potential source of enter pathogens. Estimate reports by the World Health Organization, 2018 suggest that, food-borne illnesses account 2.2 million deaths annually, out of which about 86% are children. Monney et l., 2014 reports that 65,000 people die every year in Ghana from food-borne diseases and the country economy suffering a loss of US$ 69 million.

In Tanzania the number of people suffering from food borne illness each year is difficult to estimate and there are no official records for it and also it is very difficult to establish the number of patients from hospitals because many people are suffering without the knowledge or source of the diseases example diarrhea, vomiting or abdominal cramps. An average, 15 per cent of children aged below five years are reported to have suffered from diarrhea in the preceding two weeks holding responsibilities for 9 per cent of all mortality for this age group. In some regions urban and major cities of Tanzania they have witnessed cholera and typhoid periodic outbreaks (Thomas Holbro &Young, 2013). According to report and statistics from the Ministry of Health Social Welfare, Women, Children and the Elderly, 2018; there was a cholera outbreak in Dar es Salaam in 2015 which after a very short period spread to other regions in Tanzania thus causing illness to many people and 542 deaths from 33421 reported cases across Tanzania as January 2018. In Bangladesh approximately, 30 million people suffer from food borne illnesses every year (Khairuzzaman, Chowdhury, Zaman, Mamun, & Bari, 2014).

Food borne illness

The health burden due to poor sanitation conditions, cleanliness, lack of running water and hygiene as well as improper food handling have been associated with food borne diseases. Street foods have also been associated with food borne illnesses of microbial origin with illness such as diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, fever and nausea. In Bangladesh, diarrheal diseases are very common food poisoning cases (Ossai, 2012; Battersby and Watson, 2018). These diseases are dangerous and, in some cases causes death (World Health Organization, 2014).

Food contamination and Food poisoning

Foods are usually safer when well-cooked and consumed while hot than pre-cooked foods when held for more than four hours at temperatures (15-40°C) (Hossen, Ferdaus, Hasan, Lina, Das, Barman, Paul and Roy, 2021). Some factors have been noted as potential causes for food contamination and food poisoning; poor food handlers personal hygiene, diseases caused by toxin from microbe or by human body’s reaction to the microbe, inappropriate holding temperature and misuse of chemicals for washing crockeries and dishes and cutlery. Others include; foods prepared very far in advance, semi cooked food, incorrect defrosting, poor storage, cross contamination and poor personal hygiene causing infection (Hertsmere, 2017, WHO, 2018).

There are many types of food borne illness caused by different bacteria. The most common include: Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria, E. coli 0157, Salmonella and Campylobacter. The people at risk to catch infections are babies, young children, the elderly and pregnant women who when infected immediately become very ill. However, everyone can catch the infections but it is easily possible in the vulnerable group which include; those people with weak immune system and those who already have a pre-existing illness, can seriously be affected by food borne illness (WHO, 2018).

Prevention of an outbreak of food poisoning requires food handlers to understanding practice and follow two basic principles for safe food handling: Preventing food contamination and control bacteria growth in food (WHO, 2018).

Food vendors work conditions

No doubt that street vendors work under very difficult environment facing occupational hazards and lack of proper infrastructure and facilities for the business; Some missing facilities include; firefighting equipment, sewerage, toilets, clean running water and solid waste removal or disposals. Some street vendors who does not have permanent structures or kiosks suffers a lot of transferring loads of goods, equipment, furniture, crockeries, dishes and other cooking food stocks from their residents and work places. Street vendors with money hire push carts (mkokoteni) to carry the goods but majority carry themselves.

Women street vendors with children also suffer a lot because the children who accompany their mothers to the streets lack playground thus exposing to danger and the risk of accidents in the roads. There is harassment from local authorities for street vendors nonpayment of levies and taxes. The local militia usually demand bribes and if not given they confiscate the vendors merchandise. Other poor work environment is the street food vendors work on dirty premises as some streets remain uncleaned for a number of days creating a poor work environment for the street food vendors business. The local government has responsibility of ensuring a better and clean work conducive for the street food vendors (Brown, Lyons, & Dankoco, 2010). The government should come out and show seriousness to help the entrepreneurship and help the informal sector in the country.

Consumers of Street Food

The customer surveys undertaken by FAO 2006 / 2010 and other investigators revealed that the main consumers of street foods around the world were from the informal sector, such as marching traders (machinga), vendors fellow hawkers, market vendors, construction casual labourers and hustlers. Other important categories of customers were sports people, children and students, office workers, and housewives. However, the list of consumers at Moshi town, increases to local and regional travelers and transit passengers, truck drivers, Dala dala, Boda boda and Bajaji operators, marching traders (Machinga), market vendors, construction workers, porters, shoppers, worshipers and tourist’s majority being (Back packers/ Millennium explorers). The study which was conducted at Kushtia, found that street foods were consumed across all income groups and the proportion of the daily household food budget spent was high (Biswas, Parvez, Shafiquzzaman, Nahar, and Rahman, 2010).

METHODOLOGY

Study Area

Street food safety is very essential for the majority of population, and yet it is not given its importance and rarely studied in Tanzania. Moshi is a typical tourist town in Tanzania was selected as the research object to assess food safety knowledge, and street food suppliers and consumers attitudes. Tanzania is a popular tourist destination and recently carried out a global publicized royal tour promotion as part of its marketing strategy, therefore, need to be organized and update aspects of food safety hygiene and service standards.

Moshi Town is the smallest urban authority in Tanzania it occupies 58 km2 land of which 52.6% is for housing, 2.9% commerce and finance, 9.7% industries, 2.1% urban agriculture, 4.4% transportation, hazardous land 7.0%, 0.2% cemeteries, 14.4% institutions and 6.7% recreation and forestry. The Moshi District Urban is administratively divided into 21 wards namely: Bondeni, Kaloleni, Karanga, Kiboriloni, Kilimanjaro, Kiusa, Korongoni, Longuo, Majengo, Mawenzi, MjiMpya, Msaranga, Njoro, Rau, Pasua, Ng'ambo, Mfumuni, Miembeni, Soweto, Boma Mbuzi and Shirimatunda (Google. 2022).

Moshi is the home of Mountain Kilimanjaro which is commonly referred to as the roof top of Africa located only 30s of the equators and derives its name from a local phrase “KilemaKyaro” means “that which cannot be conquered”. The mountain has two peaks; Kibo reaching a height of 5,895 meters (19,340 ft) and Mawenzi reaching a height of 5,151 meters (16899 fit). The Kibo peak despite the fact that it is located very close to the Equator is visibly snowcapped throughout the year. Some parts of the world are experiencing climatic changes so is Kibo peak whereby its snow cover is slowly declining. According to the 2022 national census; the current population of Tanzania is 61,741,120 as of Saturday, December 17, 2022 and Kilimanjaro region population is 1,861,934 while Moshi Municipality has 221,733 people being Male 108,462 and female 113,271.

The majority of women are self-employed as street vendors, food vendors, machinga, decorators, grain and vegetable sellers in the markets, pombe shop sellers, retail shop sales workers and other petty jobs. The Moshi town inhabitants are mainly business people mostly engaged in shop keeper’s business, farmers, artisans, civil servants, bankers, entrepreneurs, students, tourist guides and porters for mountain climbers.

This study was carried out in the township of Moshi which include areas; some primary schools located in Moshi town center, churches, mosques, railway station, town bus terminal, TRA offices, markets of Kiboriloni and kwa Mboya, Mawenzi hospital, construction sites at Kiboriloni, Majengo, Mawenzi and kaloleni which are the major markets of street food consumers and near the town abattoirs that also serve as points of preparation and sale of street foods.

Economic Structure of Moshi

The majority of the population in Moshi depends on income generation activities in the informal, micro and small-scale enterprises (IMSE). The major sources of income of the people are from private employment, public employment and self-employment. The residents have failed to initiate large businesses due to economic hardship, inadequate capital and lack of entrepreneurship training. However, the economic structure of Moshi is dominated by service sector businesses i.e. transportation, commuter buses, dala dala, boda boda and bajaj, nyama choma, machinga and local brew sellers.

Commerce, Finance and Industries in Moshi

The Tanzania liberalization of trade in 1985 brought economic hardship to the population and changed the people’s life style completely thus opened doors for job opportunities in the informal trade following closure and ultimate sale of some public companies, industries and institutions. Moshi town has eight retail markets and some open markets business premises for informal traders. This sector generates income for more than 50% of the population. The largest part of the Moshi population depends on the informal sector for provision of various services.

However, due to its strategic location and conducive weather, there is a constant movement of people in and out of Moshi town throughout the year. These travelers are mostly industrialists, tourists, business travelers, government officials, sports groups and those travelling for medical treatment at KCMC, educational at SMMUco, Mwenge Catholic University and Cooperative College, Moshi University, Police training school and others. The government of Tanzania has shown some initiative to revive the Moshi town economy as of recently carried out major rehabilitation, renovation and refurbishment of some public old closed industries example Magereza shoes factory which is now functioning. Others on the pipe line for major rehabilitation and renovation are the Kilimanjaro tools and machinery factory and expansion programme for the Tanzania Planting company (TPC) a sugar factory at Arusha chini.

Tourism in Moshi (Kilimanjaro)

The tourists that visit Moshi town are mostly mountain climbers, sports people, cultural, eco friends, business travelers, educational (students and parents) and those arriving for treatment in hospitals. However, there are also some tourists who arrive on transit to visit other national parks i.e. Arusha, Tarangire, Lake Manyara, Serengeti and Ngorongoro crater. Statistics show that the transit passengers include tourists stopping for luncheons and refreshments en-route to the Kilimanjaro national parks. Also, there are passengers travelling by bus or private cars and groups traveling on education or religious to and from Dar es Salaam, Tanga, Arusha, Dodoma, Mwanza, Morogoro, Iringa and Mbeya regions. The transit passengers require good quality catering services (food, beverages and snacks) and sanitation services. It is estimated that 30,000 climbers and 80,000 porters and guides hike up to summit Kilimanjaro mountain every year that is approximately 110,000 people (Mark Whitman, 2023).

Types of Food Sold by the Street Vendors

Street foods include foods prepared in streets or at home of food vendors and brought to the street for sale, and food prepared and sold at the street food stalls or kiosks consumed at home, on streets or at the workplace (Steyn et al., 2014, Chakravarty and Carnet, 1996). Those who sell street foods are recognized as street food vendors, micro-entrepreneurs and form part of the informal sector (Mukhola, 2006; Chukuezi, 2010).

In Moshi town, street foods are prepared and processed manually at home or at food stalls and sold to the public at various bus terminals, by the roadside or by itinerant vendors at the schools, churches, mosques, railway station, markets, hospitals, construction sites at Kiboriloni, Majengo, Mawenzi, kaloleni which are major markets and abattoirs in the town that are famous for the production and sale of street foods.

The most popular street foods sold in Moshi and Tanzania in general are Nyama choma, French fried potatoes and eggs (chips mayai) with beef skews (mishikaki) also complete meals of staple maize meal porridge (Ugali), pilaf, biriani or Bananas or plain rice served with stewed, fish, fried or grilled beef, Maize and beans (Makande), mutton, chicken or beans, some served with gravies, spices, hot chilies (michuzi mikali), and mixed salads (kachumbali), mchicha, cabbage and green vegetables.

Other foods include; snacks, meat portions of roasted chicken heads, chicken wings, gizzards, fried beef and chicken sausages, beef skews (mishikaki) and variety of fish tilapia from nyumba ya Mungu dam, saladines (dagaa), and nyama choma, boiled and fried cassava (chips dume), cooked and fried yams, boiled and grilled maize (sweet corn), fried chicken, gizzards, kuku wa kupaka.

Others include, Soup (supu), kuku za kukaanga (vichwa, miguu, utumbo), cassava and fried fish (mihogo na samaki za kukaaanga au (tezi dume), buns (maandazi), vegetables, fruits, wine grapes (zabibu), homemade ice cream, homemade fruit juices, samosas, cashew nuts, sugarcane and juices, ubuyu, porridge, mtori etc). Biting like samosas, ground nuts, tende (dates), ubuyu, variety of fruits mangoes, oranges, bananas, pineapples, papayas, water melon and beverages such as tea, coffee, ginger (tangawizi).

Study Design

During the research design process of this study, the researcher was guided by the positivism paradigm, selected the quantitative approach as its best suits and fulfils the aim and objectives of the study as it provides space to raise opinion about the characteristics of people, specifies the level of attitudes held by people and provides results that can be condensed into statistics and is in line with the methods employed by the majority of existing studies in the mainstream literature (Roomes, 2018). This study apart from street vending it also include vendors from; stationary food vending units (Kiosk), mobile food vending push carts such as (mkokoteni) and wheel barrow (toroli), motor bikes (guta) and vans and those carried in boxes and food warmers (kidedea).

Sampling Technique

A walk-through survey of randomly selected food vending sites was done and a total of 125 vending units were observed using a checklist whereby to participate in the survey simple random sampling technique was carried out selecting one vendor per site. The study was carried out over a period of six months from September 2021 to February, 2022 among street food vendors/vending units and street food consumers in the Moshi town, Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania.

Data Collection Tools

A structured administered questionnaire was used to collect data on background characteristics of respondents. An observational checklist adapted from the “WHO” essential requirement for the safety of street-vended foods” was used to determine a sanitary condition of food vending sites/vending practices of food vendors (Cortese et al., 2016). The study instrument was pretested among selected street food vending sites/vendors operating in Moshi urban and to the street food consumers in the study area.

Questionnaire

This study selected and used Likert five-point numerical rating scale 1. Strongly agree; 2. Agree; 3. Neutral; 4. Disagree; 5. Strongly disagree to measure responses because the scale is widely used and extensively tested in both marketing and social science in the field of tourism marketing research and has been acknowledged by researchers as a credible tool in measuring respondents' attitude and perceptions (Bhuiyan, 2016). The study also adopted the Yes and No questions for street food consumers. This was necessary because most of the consumers appeared to be on hurry without spare time.

Data Analysis

Questionnaires were screened for completeness, coded, and entered into excel for analysis.

Socio demographic Characteristics of Street food vendors and consumers

The street food vendors of Moshi town are not enumerated in the formal sector of country’s economy but are recognized as part of the informal sector which normally comprise businesses that are irregular, unstable and have marginal economic activities. This implies that their existence is recognized but not given dual attention to their numbers, no official systematic documentation for the scale of this business as well as its viability. In Moshi Street vending is probably the third most important employment opportunity for the urban poor after old clothes traders (mitumba), marching traders (machinga) and commuter transporters (dala dala). It is estimated that there are more than 4000 street food vendors in Moshi approximate 2.5% of the population serving more than 120,000 complete meals per day to consumers (Table 1).

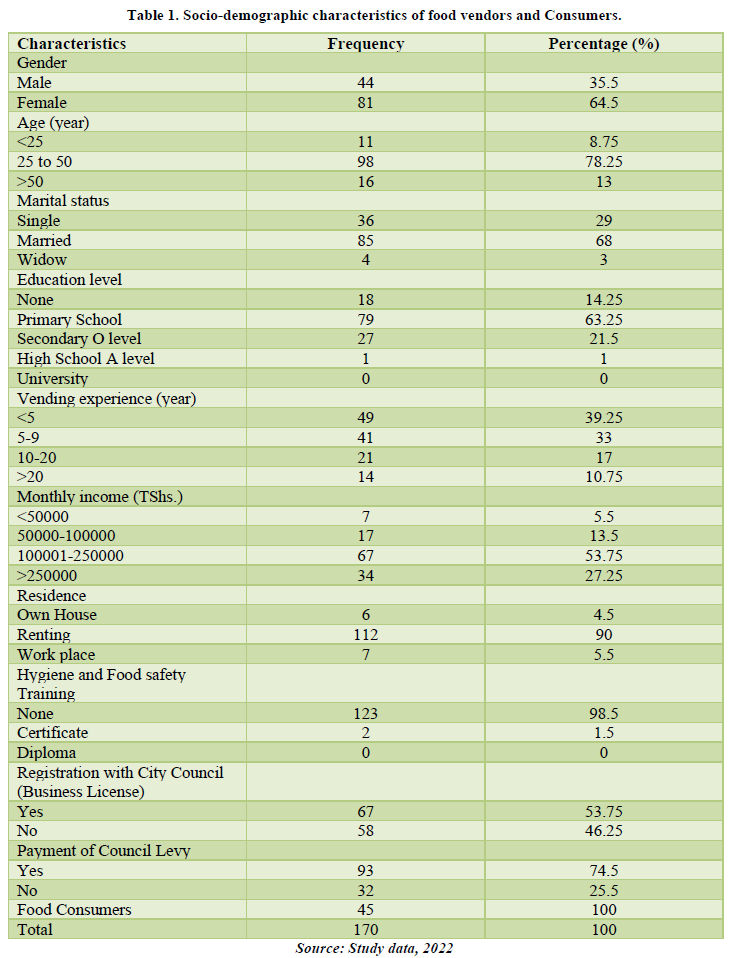

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the 170 respondents (45 consumers and 125 food vendors). The study was a quantitative descriptive where a structured questionnaire was used to collect self-reported data from street food vendors and consumers. The questions were asked in the national language "Kiswahili" and the responses were translated into the English language. Subsequently, data were triangulated to present an overall impression of the food vendor's healthy practice and a check list was used to collect and record data (Cortese et al., 2016).

The majority of street food vendors were females, with a higher proportion of 64.5% and male 35.5% respectively. The female predominance of the food vending business in Moshi is due to the fact that first it is a tradition in the region the majority of the household’s females are the bread winners or otherwise. Age ranged from 25 to 60 years. A group of 25 years and below was 8.75% being minority. Consumer ages ranged between 7 years and 80 years. Food vendors marital status were single 29%; married 68% and widow3% while consumers marital status were singles71% being majority as most of the consumers were still young and married 29%. Food vendors educational level were 14.25% had no formal education, while 63.25 being majority had primary school education, whereas only 1% had A level high school education and O level secondary school were 21.5%.

Street food vendors knowledge on hygiene and safety showed 98.5% had not attended training and only 1.5% had attended recognized professional training and awarded a certificate. This demonstrated that the food vendors had low level of food safety knowledge and experience; they had a poor understanding and exposure of safe food handling. Further, it was observed the shortage and inadequate equipment and facilities in the work premises and unhygienic practices on vending foods. However, the food vendors level of food hygiene knowledge was measured satisfactory acceptable (Table 2).

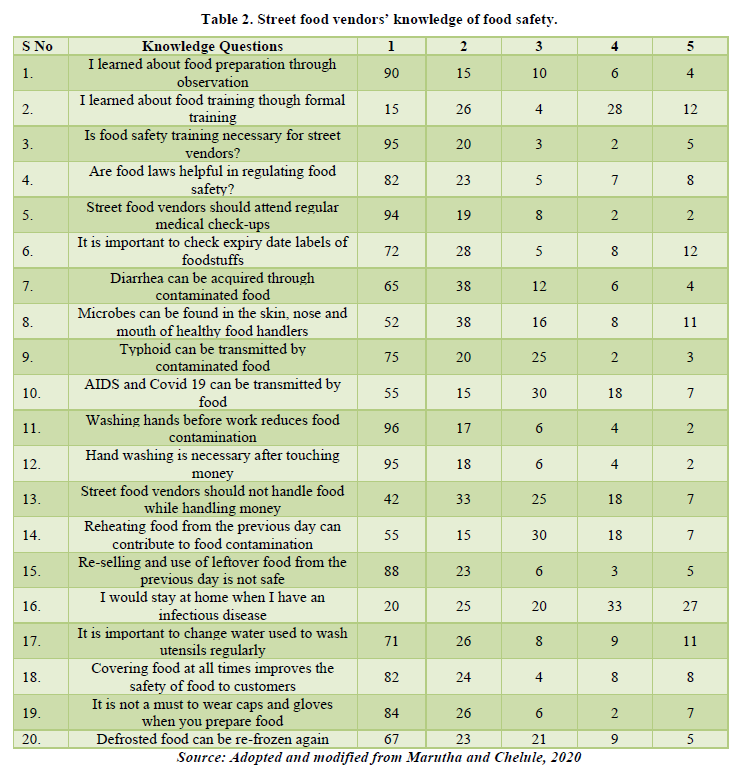

Food street vendors were asked a number of questions regarding knowledge of food safety, general hygiene and personal hygiene to assess their knowledge of food safety. Generally, the food vendors do not have adequate washing facilities, and some vendors report on their duties without taking a proper bath. The majority of food vendors acquired their knowledge on cooking food on the job through observation (84%) and 1.5% through formal training while food vendors 92% found that food safety training was necessary for street vendors; and the remainder 8% responded otherwise. Moreover, some food handlers washed their hands in the same bucket used for cleaning utensils, which may lead to the contamination of food with fecal matter.

Majority, 90.4% of the vendors knew that washing hands before handling food reduced food contamination and 84.8% find that covering food at all times improves the safety of food and majority of participants (80%,) correctly knew the importance of checking the expiry date of foodstuffs on the container labels before using them. 60% of street food vendors knew that they should not handle food while handling money and 90.4% find that hand washing is necessary after touching money. The food venders 88.8% correctly knew that re-selling and use of leftover food from the previous day was not a safe practice and 72% knew that defrosted food can be re-frozen again same 56% agrees that reheating food from the previous day can contribute to food contamination due to change of temperature.

Foods and ingredients are subjected to repeated contamination from unwashed hands and the materials used for wrapping, such as banana leaves, old newspapers, paper bags and reusable polyethylene bags. Food vendors expressed their knowledge on food contamination that 82.4% said bloody diarrhea can be acquired through contaminated food; and 76% said typhoid can be transmitted by contaminated food while 56% declared that AIDS and Covid 19 can be transmitted by food.

Most importantly 97% food vendors pointed out that it is important to change water used to wash utensils regularly; and 88% of food vendors noted that it is not a must to wear caps and gloves when you prepare food. The food vendors also shared their ignorance about infection diseases when 36% only agrees to stay at home when they have an infectious disease while 72% knows that microbes can be found in the skin, nose and mouth of healthy food handlers.

Many vendors are not aware of the need to wear clean and appropriate clothes. However, some of the female vendors worn chef’s hat and aprons. Some 88% of food vendors agree that it is not necessary to wear caps and gloves when food is prepared (Table 3).

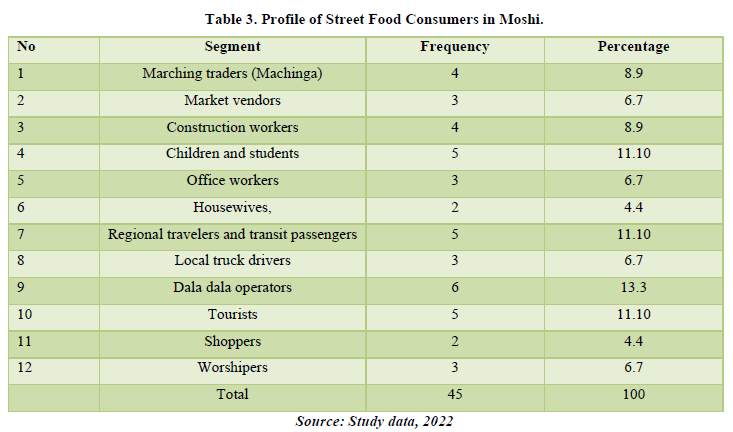

In Table 3 Majority of the consumers of the street food vendors were (dala dala) operators 13.3%, followed by children and students 11.10%, regional travelers and transit passengers 11.10%, tourists, 11.10%, marching traders (Machinga) 8.9% construction workers 8.9 %, market vendors 6.7 %, office workers 6.7 %, local truck drivers 6.7%, worshipers 6.7%, house wives 4.4 % and shoppers 4.4 %, both men and women consumed the meals on premises or as take-away depending on individual convenience. The vendors also reported that some office workers including high ranking government officials and managers and lecturers send their messengers for food and consume in their offices. This is similar to observations by Ohiokpehai (2003) that students and the homeless in Botswana were reliant on street foods. The street food consumers in Botswana included both the working class and professionals (Ohiokpehai, 2003).

Food safety attitudes of street food Consumers

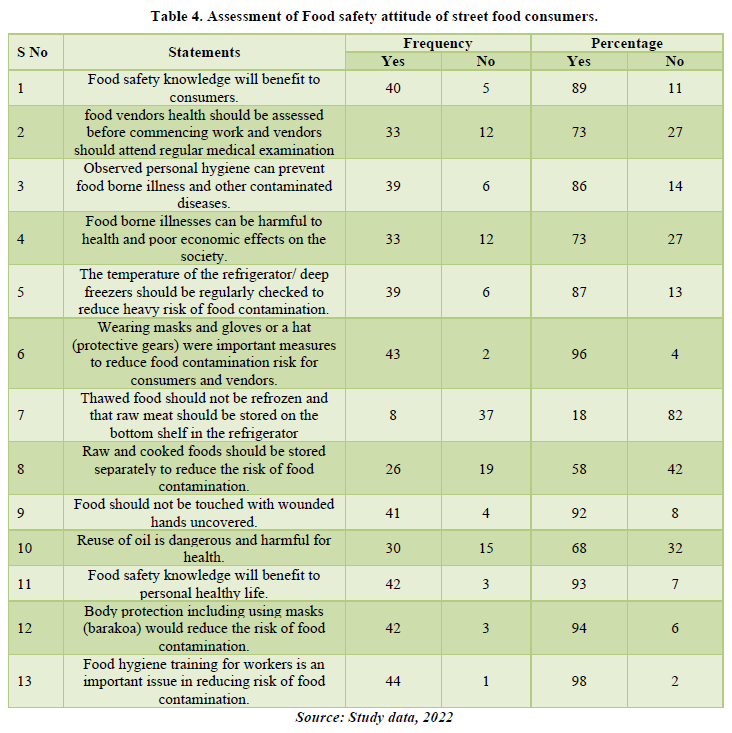

Table 4 shows Street food consumer’s majority 89% had a thorough understanding of food safety handling, food borne illness and hygiene issues. Street food consumers 73% agree that food vendor health should be examined before commencing work and vendors should attend regular medical examination. Food consumers’ majority 86% agreed that good personal hygiene could prevent food borne illness. Food consumers 73% had opinion that food borne illnesses can have harmful health and economic effects in the society.

Street food consumers 87% agree that the temperature of the refrigerator/ deep freezers should be regularly checked to reduce the risk of food contamination. Majority of consumers 96% considered wearing masks(barakoa) and gloves or a hat (protective gears) were important decision to reduce food contamination risk for consumers and vendors. Only 18% food consumers thought thawed food should not be refrozen and that raw meat should be stored on the bottom shelf in the refrigerator. Meanwhile, 58% agreed that raw and cooked foods should be stored separately to reduce the risk of food contamination. Majority of food consumers 92% agreed that food should not be touched with wounded hands and 68% cautioned that reuse of oil is harmful for health. 93% of food consumers mentioned about food safety knowledge that would benefit to personal life. Many food consumers 94% agreed with protective gears including wearing masks that would reduce the risk of food contamination and 98% insist food hygiene training for workers is an obligation issue in reducing risk of food contamination.

Major Findings / Discussion and Summary

This survey statistics demonstrated that in Moshi town food street vendors prepare and sell food items cooked and raw average 120,000 meals to consumers or 75.97 percent of Moshi total population per day. This data indicates that each vendor serves 30 meals to consumers per day on average. The street food vendors’ contribution to the labor market of Moshi is significant and selling street food is not a marginal economic activity, but rather a visible and highly appreciated social practice that is economically efficient, convenient, affordable, and deeply attached to urban life economy.

Majority of street vendors did not have access to tap running water instead unacceptable used portable bucket water to vending sites. Likewise, street vendors handling food with bare hands is a very serious practice which is a not recommended for the sake of food safety. The poor food handling practice could create chances of cooked food contaminated by pathogens that are not visible to the eye. Contaminated food can cause food borne illnesses to consumer such as diarrhea, nausea and vomiting.

Food consumers mentioned about food safety knowledge that would benefit to personal life healthy. Very surprisingly, the few tourists interviewed had a lot of praise of street food claiming that the food is fresh, very tasty, palatable, and cheap without any complications to the presentation and the servers were friendly too. Majority of the local consumers had no complains only praising about how convenient is the food on their personal life and some jokingly said as long as street food is available, they don’t consider marriage.

Most food vendors admitted to re-sale left-over foods to consumers the following day after reheating the food. Despite having the knowledge of food safety, the street food vendors insisted traditionally eating or re-sell left-over food is not bad provided that the food is stored in a safe place. For essential safe food handling practices it is important for food vendors adhering to food hygiene rules and standards.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study concludes that significantly and practically it is riskier to sell cooked food than uncooked food in the streets. It has been noted that street food vendors have adequate knowledge on safe food handling practices, although this knowledge is not always demonstrated into practices.

Street foods are prepared, sold and consumed without taking into consideration the important issues of food safety or quality neither on the producer nor on the consumer side. Usually, street food vendors have a small profit margin from food sales and are encouraged to keep material cost low by buying foodstuffs from whole sellers. and set minimum standards to the food quality and need to be enforced.

Selling food in open space exposes food to microbes, heat, rain, flies, smoke and dust, which compromises food safety. It is recommended that authorities should inform the public on food safety practice and health promotion programme. Street food vendors training on food safety should be conducted regularly. There are many retired hotel and hospitality professionals who could conduct these courses. Serious steps should be taken to improve street food operating conditions and facilities, providing clean protected structures, access to tap running water, and efficient waste collection and disposal systems to further improve street food safety and sanitation.

There is a need for the development of a national food safety standards and strategic action plan for food hygiene, safety and personal hygiene that will consolidate legislations, local bye-laws on food safety. The set standards for food hygiene and safety that street food vendors must comply need to be outlined on a national level and made public to all stake holders. The factors on which strategic action plan should be identified by preliminary studies of the street food operations based with initial inventory of the street food trade and the aforementioned. On job training programme with HACCP based studies is recommended. Regular inspections on premises, sanitation, utility supply, food quality, personal hygiene, safety, hygiene and cleanliness standards and efficient garbage collection should be carried out on daily basis. Moshi town is the home of Mount Kilimanjaro as well as it is a tourist destination therefore, it must be given its dual recognition and respect.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study was conducted in an urban setting (central business district) without external funding. This study findings may not be similar to other settings such as to major cities, Metropolitan and countryside. The study data was collected from Moshi town areas with limited resources, such as tap water and electricity supply. These findings may not be the same for another urban setting where basic resources, such as water and electricity and garbage collection are available and more reliable. Therefore, your interpretation to the study findings should include these arguments.

- Al Mamun, M., Rahman, M. & Turin, T. (2013). Microbiological Quality of Selected Street Food Items Vended by School-Based Street Food Vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 166, 413-418.

- Addo-Tham, R., Appiah, E., Vampere, H., Acquah, E., & Gyimah, A., et al. (2020). Knowledge on Food Safety and Food-Handling Practices of Street Food Vendors in Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ghana. Advances in Public Health, 1-7.

- Akwasi, A. (2020). Knowledge on Food Safety and Food-Handling Practices of Street Food Vendors in Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ghana. Advances in Public Health, 1-7.

- Anandhi, N., Janani, & Krishnaveni, N. (2015). Microbiological Quality of Selected Street-Vended Foods in Coimbatore, India. African Journal of Microbiological Research, 9, 757-762.

- Battershy, J., & Watson (2018). Urban Food Systems Governance and Poverty in African Cities. London Routledge.

- Battersby, J., Hayson, G., Tawodzera, G., & Crush, J. (2014). Food System and Food Security Study for the City of Cape Town.

- Bhuiyan, M. (2016). Socio Economic Impact of Tourism in Cox’s Bazar A Study of Local Residents Attitude. A Dissertation for Award of PhD degree at Dhaka University, Bangladesh.

- Biswas, S., Parvez, M., Safiquzzaman, M., Nahar, S., & Rahman, M. (2010). Isolation and Characterization of Escherichia coli in Ready-to-Eat Foods Vended in Islamic University, Kushtia, Journal of Bio-Science, 18, 99-103.

- Brown, A, Lyons, M, & Dankoco, I. (2010). Street Traders and the Emerging Spaces for Urban Voice and Citizenship in African Cities. Urban Studies, 47, 666-683.

- Cortese, R., Veiros, M., Feldman, C., & Cavalli, S. (2016). Food Safety and Hygiene Practices of Vendors during the Chain of Street food Production in Florianopolis, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. Food Control, 62, 178-186.

- Chukuezi, C. (2010). Food Safety and Hygiene Practices of Street Food Vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Studies in Sociology of Science, 1, 50-57.

- Chakravarty, I. & Carnet, C. (1996). Street Foods in Calcutta. Food Nutrition and Agriculture, 18, 7.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2010). The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1683e/i1683

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO. (2013). The state of food insecurity in the world the multiple dimensions of food security. Rome FAO.

- Khairuzzaman, M., Chowdhury, F. M., Zaman, S., Al Mamun, A., & Bari, M. L. (2014). Food Safety Challenges towards Safe, Healthy, and Nutritious Street Foods in Bangladesh. International Journal of Food Science, 1-9.

- Khomotso J., Marutha & Chelule, P (2020). FOODS Article Safe Food Handling Knowledge and Practices of Street Food Vendors in Polokwane Central Business District Department of Public Health School of Health Care Sciences Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 0001 Pretoria South Africa MDPI.

- King, L., Awumbila, B., Canacoo, E., & Ofosu-Amaah, S. (2000). An Assessment of the Safety of Street Foods in the Ga district of Ghana Implications for the Spread of Zoonoses. Acta Tropical, 76, 39-43.

- Lamuka PO. (2014). Public Health Measures Challenges of Developing Countries in Management of Food Safety. Encyclopedia of Food Safety, pp: 20.

- Lihua Ma, Hong Chen, Huizhe Yan, Lifeng Wu, & Wenbin Zhang. (2019). Food Safety Knowledge Attitudes and Behavior of Street Food Vendors and Consumers in Handan a third tier City in China. BMC Public Health, 19.

- Muinde, O. K & Kuria, E. (2005). Hygiene and Sanitary Practices of Vendors of Street Foods in Nairobi, Kenya. African Journal of Food, Agriculture Nutrition and Development, 5, 1-13.

- Monney, I., Agrei, D., Ewoenam, B., Priscilla, C., & Nyaw, S. (2014) Food Hygiene and Safety Practices among the Street Food Vendors: An Assessment of Compliance Institutional and Legislative Framework in Ghana. Scientific and Academic Publishing Food and Public Health, 4, 306-315.

- Mukhola, M. (2006). Guidelines for an Environmental Education Training Programme for Street Food Vendors in Polokwane City. Ph.D. Thesis University of Johannesburg South Africa.

- Muzaffar, A, Huq, I, & Mallik., B, (2009). Entrepreneurs of the Streets: An Analytical Work on the Street Food Vendors of Dhaka city. International Journal of Business and Management, 4, 80-88.

- Naibbi, A., & Healey, R. (2012). Northern Nigeria Dependence on Fuel wood: Insights International Journal of Humanities and Social Science.

- Ohiokpehai, O. (2003). Nutritional aspects of street foods in Botswana. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 2, 76-81.

- Okojie, P.W., Isah, E.C. (2014). Sanitary conditions of food vending sites and food handling practices of street food vendors in Benin City Nigeria Implication for food hygiene and safety. Journal of Environmental and Public Health.

- Ossai, O. (2012). Bacterial Quality and Safety of Street Vended Foods in Delta State, Nigeria. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 2, 2224-3208.

- The Ministry of Health Social Welfare Women Children and the Elderly (2018). Disease outbreak Cholera Tanzania 2018.

- Roever, R., Boyce, M., Stenhouse, G. (2010). Grizzly Bear Movements Relative to Roads: Application of Step Selection Functions. https (Biodiversity Conservation) 18/174 (Ecology). John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 33, 1113-1122.

- Roomes, N. (2018). Residents Perception of their Quality of Life and Tolerance of Tourism as a Diagnostic Model for Assessing the Social Carrying Capacity in Small Island Developing States: The Case of Ocho Rios, Jamaica. A Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy Degree at the College of the Oklahoma State University, pp: 273

- Steyn, N., McHiza, Z., Hill, J., Davids, Y., Venter, I. (2014). Nutritional Contribution of Street Foods to the Diet of People in Developing Countries A Systematic Review. Public Health Nutrition, 17, 1363-74.

- Thomas,J, Holbro, N & Young, D. (2013). A Review of Sanitation and Hygiene in Tanzania.

- Toh P.S, Birchenough A. (2000). Food Safety Knowledge and Attitudes: Culture and Environment Impact on Hawkers in Malaysia.: Knowledge and Attitudes Are Key Attributes of Concern in Hawker Food handling Practices and Outbreaks of Food Poisoning and Their Prevention. Food Control, 11, 447-452.

- Toufik Hossen, Jannatul Ferdaus, Mohibul Hasan, Nazia Nawshad, Lina Ashish Kumar, et al. (2021). Food Safety Knowledge Attitudes and Practices of Street Food Vendors in Jashore Region, Bangladesh. Food Science Technol (Campinas) 41 (suppl 1).

- Winarno, F. G., & Alain, A. (1991). Street Foods in Developing Countries Lessons from Asia. Rome FAO.

- World Health Organization WHO. (2014). WHO Initiative to Estimate the Global Burden of Food Borne Diseases: Fourth Formal Meeting of the Food borne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG) Sharing New Results, Making Future Plans and Preparing Ground for the Countries. Geneva WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Africa (2018). By Disease outbreak Cholera Tanzania.